Diction for Singing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

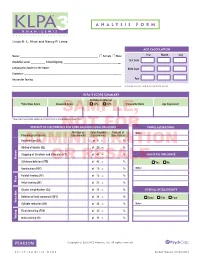

Sample, Not for Administration Or Resale

ANALYSIS FORM Linda M. L. Khan and Nancy P. Lewis Age Calculation Name: ______________________________________________________ u Female u Male Year Month Day Test Date Grade/Ed. Level: __________ School/Agency: __________________________________________ Language(s) Spoken in the Home: ___________________________________________________ Birth Date Examiner: ____________________________________________________________________ Reason for Testing: ______________________________________________________________ Age ____________________________________________________________________________ Reminder: Do not round up to next month or year. KLPA–3 Score Summary Confidence Interval *Total Raw Score Standard Score 90% 95% Percentile Rank Age Equivalent SAMPLE,– * Raw score equals total number of occurrences of scored phonological processes. Percent of OccurrenceNOT for Core Phonological ProcessesFOR Vowel Alterations Number of Total Possible Percent of Notes: Phonological Process Occurrences Occurrences Occurrences DeaffricationADMINISTRATION (DF) of 8 = % Gliding of liquids (GL) of 20 = % Stopping of fricatives and affricates (ST) of 48 = % Dialectal Influence Manner OR RESALE Stridency deletion (STR) of 42 = % Yes No Vocalization (VOC) of 15 = % Notes: Palatal fronting (PF) of 12 = % Place Velar fronting (VF) of 23 = % Cluster simplification (CS) of 23 = % Overall Intelligibility Deletion of final consonant (DFC) of 36 = % Good Fair Poor Reduction Syllable reduction (SR) of 25 = % Notes: Final devoicing (FDV) of 35 = % Voicing Initial voicing -

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin Essay Title: The sound system of Japanese This essay aims to introduce the sound system of Japanese, including the inventories of consonants, vowels, and diphthongs. The phonological variations of the sound segments in different phonetic environments are also included. For the illustration, word examples are given and they are presented in the following format: [IPA] (Romaji: “meaning”). Consonants In Japanese, there are 14 core consonants, and some of them have a lot of allophonic variations. The various types of consonants classified with respect to their manner of articulation are presented as follows. Stop Japanese has six oral stops or plosives, /p b t d k g/, which are classified into three place categories, bilabial, alveolar, and velar, as listed below. In each place category, there is a pair of plosives with the contrast in voicing. /p/ = a voiceless bilabial plosive [p]: [ippai] (ippai: “A cup of”) /b/ = a voiced bilabial plosive [b]: [baɴ] (ban: “Night”) /t/ = a voiceless alveolar plosive [t]: [oto̞ ːto̞ ] (ototo: “Brother”) /d/ = a voiced alveolar plosive [d]: [to̞ mo̞ datɕi] (tomodachi: “Friend”) /k/ = a voiceless velar plosive [k]: [kaiɰa] (kaiwa: “Conversation”) /g/ = a voiced velar plosive [g]: [ɡakɯβsai] (gakusai: “Student”) Phonetically, Japanese also has a glottal stop [ʔ] which is commonly produced to separate the neighboring vowels occurring in different syllables. This phonological phenomenon is known as ‘glottal stop insertion’. The glottal stop may be realized as a pause, which is used to indicate the beginning or the end of an utterance. For instance, the word “Japanese money” is actually pronounced as [ʔe̞ ɴ], instead of [je̞ ɴ], and the pronunciation of “¥15” is [dʑɯβːɡo̞ ʔe̞ ɴ]. -

A Case Study of Norwegian Clusters

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title Morphological derived-environment effects in gestural coordination: A case study of Norwegian clusters Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5mn3w7gz Journal Lingua, 117 ISSN 0024-3841 Author Bradley, Travis G. Publication Date 2007-06-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Bradley, Travis G. 2007. Morphological Derived-Environment Effects in Gestural Coordination: A Case Study of Norwegian Clusters. Lingua 117.6:950-985. Morphological derived-environment effects in gestural coordination: a case study of Norwegian clusters Travis G. Bradley* Department of Spanish and Classics, University of California, 705 Sproul Hall, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616, USA Abstract This paper examines morphophonological alternations involving apicoalveolar tap- consonant clusters in Urban East Norwegian from the framework of gestural Optimality Theory. Articulatory Phonology provides an insightful explanation of patterns of vowel intrusion, coalescence, and rhotic deletion in terms of the temporal coordination of consonantal gestures, which interacts with both prosodic and morphological structure. An alignment-based account of derived-environment effects is proposed in which complete overlap in rhotic-consonant clusters is blocked within morphemes but not across morpheme or word boundaries. Alignment constraints on gestural coordination also play a role in phonologically conditioned allomorphy. The gestural analysis is contrasted with alternative Optimality-theoretic accounts. Furthermore, it is argued that models of the phonetics-phonology interface which view timing as a low-level detail of phonetic implementation incorrectly predict that input morphological structure should have no effect on gestural coordination. The patterning of rhotic-consonant clusters in Norwegian is consistent with a model that includes gestural representations and constraints directly in the phonological grammar, where underlying morphological structure is still visible. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ GEMINATED LIQUIDS in JAPANESE: a PRODUCTION STUDY a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisf

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ GEMINATED LIQUIDS IN JAPANESE: A PRODUCTION STUDY A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in LINGUISTICS by Maho Morimoto March 2020 The Dissertation of Maho Morimoto is approved: Grant McGuire, Chair Jaye Padgett Ryan Bennett Quentin Williams Acting Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Maho Morimoto 2020 Contents List of Figures vi List of Tables ix Abstract xvi Dedication xviii Acknowledgments xix 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Introduction . .1 1.2 Japanese phonology . .2 1.2.1 Vowel and consonant inventories . .2 1.2.2 Morpheme classes and lexical domains . .2 1.2.3 Geminates in Japanese . .3 1.2.4 Liquid consonant in Japanese . .6 1.3 Geminated liquids in Japanese . 11 1.3.1 Avoidance of geminated liquids . 11 1.3.2 Appearance of geminated liquids . 13 1.3.3 Issues in geminated liquids . 15 1.4 Outline of the dissertation . 17 2 Acoustic Characteristics of Geminated Liquids in Japanese 18 2.1 Introduction . 18 2.1.1 Acoustic characteristics of liquids . 19 2.1.2 Acoustic characteristics of geminates . 21 2.2 Method . 24 2.2.1 Subjects . 24 2.2.2 Speech materials . 25 2.2.3 Procedure . 28 2.2.4 Measurements . 29 iii 2.3 Durational results & discussion . 30 2.3.1 Consonant duration . 30 2.3.2 Preceding vowel duration . 34 2.3.3 Following vowel duration . 37 2.3.4 VCV duration . 40 2.3.5 Discussion . 42 2.4 Non-durational results & discussion . 43 2.4.1 Intensity on the consonants . -

Phonological Differences Between Japanese and English: Several Potentially Problematic

1 Title: Phonological Differences between Japanese and English: Several Potentially Problematic Areas of Pronunciation for Japanese ESL/EFL Learners Author: Kota Ohata Indiana University of Pennsylvania Bio Statement Kota Ohata earned his B.A. degree from Kyoto University of Foreign Studies in 1994, a M.A. in TESOL from West Virginia University in 1996. After a few years of EFL teaching back in Japan, he returned to the U.S. for the pursuit of doctoral degree in the area of applied linguistics. Recently Kota Ohata completed his dissertation and received a Ph.D. in Composition & TESOL from Indiana University of Pennsylvania. 2 Abstract In light of the fact that L2 pronunciation errors are often caused by the transfer of well-established L1 sound systems, this paper examines some of the characteristic phonological differences between Japanese and English. Comparing segmental and suprasegmental aspects of both languages, this study also discusses several problematic areas of pronunciation for Japanese learners of English. Based on such contrastive analyses, some of the implications for L2 pronunciation teaching are drawn. Introduction The fact that native speakers of English can recognize foreign accents in ESL/EFL learners’ speech such as Spanish accents, Japanese accents, Chinese accents, etc., is a clear indication that the sound patterns or structure of their native languages have some influence on the speech or production of their second language. In other words, it is quite reasonable to say that the nature of a foreign accent is determined to a large extent by a learner’s native language (Avery & Ehrlich, 1992). Thus, the pronunciation errors made by second language learners are considered not to be just random attempts to produce unfamiliar sounds but rather reflections of the sound inventory, rules of combining sounds, and the stress and intonation patterns of their native languages (Swan & Smith, 1987). -

What /R/ Sounds Like in Kansai Japanese: a Phonetic Investigation of Liquid Variation in Unscripted Discourse

What /r/ Sounds Like in Kansai Japanese: A Phonetic Investigation of Liquid Variation in Unscripted Discourse by Thomas Judd Magnuson B.A., University of British Columbia, 1998 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Linguistics © Thomas Judd Magnuson, 2008 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii What /r/ Sounds Like in Kansai Japanese: A Phonetic Investigation of Liquid Variation in Unscripted Discourse by Thomas Judd Magnuson B.A., University of British Columbia, 1998 SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE Dr. Hua Lin, Supervisor (Department of Linguistics) Dr. John H. Esling, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) Dr. Tae-Jin Yoon, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) iii Supervisory Committee Dr. Hua Lin, Supervisor (Department of Linguistics) Dr. John H. Esling, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) Dr. Tae-Jin Yoon, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) ABSTRACT Unlike Canadian English which has two liquid consonant phonemes, /ɹ, l/ (as in right and light ), Japanese is said to have a single liquid phoneme whose realization varies widely both among speakers and within the speech of individuals. Although variants of the /r/ sound in Japanese have been described as flaps, laterals, and weak plosives, research that has sought to quantitatively describe this phonetic variation has not yet been carried out. The aim of this thesis is to provide such quantification based on 1,535 instances of /r/ spoken by four individuals whose near-natural, unscripted conversations had been recorded as part of a larger corpus of unscripted Japanese maintained by Dr. -

Articulatory Characterization of English Liquid-Final Rimes

1 2 3 4 5 6 Articulatory Characterization of 7 8 English Liquid-Final Rimes 9 10 Michael Proctor 11 Department of Linguistics, Macquarie University 12 13 Rachel Walker, Caitlin Smith 14 Department of Linguistics, University of Southern California 15 16 T¨undeSzalay 17 Department of Linguistics, Macquarie University 18 19 Louis Goldstein, Shrikanth Narayanan 20 Department of Linguistics, University of Southern California 21 22 23 24 25 Abstract 26 27 Articulation of liquid consonants in onsets and codas by four speakers of General American English was 28 examined using real-time MRI. Midsagittal tongue posture was compared for laterals and rhotics produced 29 30 in each syllable margin, adjacent to 13 different vowels and diphthongs. Vowel articulation was examined in 31 words without liquids, before each liquid, and after each liquid, to assess the coarticulatory influence of each 32 segment on the others. Overall, nuclear vocalic postures were more influenced by coda rhotics than onset 33 34 rhotics or laterals in either syllable margin. Laterals exhibited greater temporal and spatial independence 35 between coronal and dorsal gestures. Rhotics were produced with a variety of speaker-specific postures, 36 37 but were united by a greater degree of coarticulatory resistance to vowel context, patterns consistent with 38 greater coarticulatory influence on adjacent vowels, and less allophonic variation across syllable positions 39 than laterals. 40 41 Keywords: liquid consonant, rhotic, lateral, coarticulation, syllable structure 42 43 44 1. Introduction 45 46 Liquid consonants in American English exhibit asymmetries with respect to the range of contrasts in co- 47 48 occurring vowels in the rime. -

Harmony Systems

8 Harmony Systems SHARON ROSE AND RACHEL WALKER 1 Introduction This chapter addresses harmony systems, a term which encompasses consonant harmony, vowel harmony, and vowel-consonant harmony. Harmony refers to phonological assimilation for harmonic feature(s) that may operate over a string of multiple segments. This can be construed in one of two ways. Two segments may interact “at a distance” across at least one (apparently) unaffected segment, as shown for consonant harmony in (1a). Or, a continuous string of segments may be involved in the assimilation, as shown for vowel-consonant harmony in (1b). The subscripts refer to features or feature sets. (1) a. distance harmony → consonant harmony Cx Vy Cz Cz Vy Cz b. continuous harmony → vowel-consonant harmony Cx Vy Cz Cz Vz Cz Although only three segments are represented in the diagram in (1), harmony can apply to longer strings. As for vowel harmony, it can operate at a distance depending on how one construes intervening consonants and/or vowels that are apparently unaffected by the assimilation. It may also be construed as continuous if intervening segments participate in harmony. Furthermore, vowel-consonant harmony can operate at a distance, skipping over some segments. In this chapter, we fi rst provide a descriptive overview of the basic patterns of the harmony systems outlined in (1), with a focus on the triggers (segments that cause harmony) and targets (segments that undergo harmony). We also touch on blocking segments (ones that halt harmony) and transparent segments (ones that The Handbook of Phonological Theory, Second Edition. Edited by John Goldsmith, Jason Riggle, and Alan C. -

Lecture Notes and Other Handouts for Introductory Phonology

Lecture Notes and Other Handouts for Introductory Phonology: A Course Packet Steve Parker GIAL and SIL International Dallas, 2013 Copyright © 2013 by Steve Parker and other contributors Preface This set of materials is designed to be used as handouts accompanying an introductory course in phonology, particularly at the undergraduate level. It is specifically intended to be used in conjunction with Stephen Marlett’s 2001 textbook, An Introduction to Phonological Analysis. The latter is currently available for free download from the SIL Mexico branch website. However, this course packet could potentially also be adapted for use with other phonology textbooks. The materials included here have been developed by myself and others over many years, in conjunction with courses in introductory phonology taught at SIL programs in North Dakota, Oregon, Dallas, and Norman, OK. Most recently I have used them at GIAL. Two colleagues in particular have contributed significantly to many of these handouts: Jim Roberts and Steve Marlett, to whom my thanks. I would also like to express my appreciation and gratitude to Becky Thompson for her very practical service in helping combine all of the individual files into one exhaustive document, and formatting it for me. Many of the special phonetic characters appearing in these materials use IPA fonts available as freeware from the SIL International website. Unless indicated to the contrary on specific individual handouts, all materials used in this packet are the copyright of Steve Parker. These documents are intended primarily for educational use. You may make copies of these works for research or instructional purposes (under fair use guidelines) free of charge and without further permission. -

Normal Acquisition of Consonant Clusters

Tutorial Normal Acquisition of Consonant Clusters Sharynne McLeod* Jan van Doorn Vicki A. Reed The University of Sydney, Australia Children’s acquisition of adult-like speech 70 years to describe children’s normal acquisi- production has fascinated speech-language tion of consonant clusters. Articulatory, phono- pathologists for over a century, and data gained logical, linguistic, and acoustic approaches to from associated research have informed every the development of consonant clusters are aspect of speech-language pathology practice. reviewed. Data from English are supplemented The acquisition of the consonant cluster has with examples from other languages. Consider- received little attention during this time, even ation of the information on consonant cluster though the consonant cluster is a common development revealed 10 aspects of normal feature of speech, its acquisition is one of the development that can be used in speech- most protracted of all aspects of children’s language pathologists’ assessment and speech development, and the production of analysis of children’s speech. consonant clusters is one of the most common difficulties for children with speech impairment. Key Words: normal development, consonant This paper reviews the literature from the past clusters, phonology, children’s speech onsonant clusters are a feature of many of the strength). A further complicating factor is that morphologi- world’s languages. In a study of 104 world cal endings create even more complex phoneme sequences C languages, based on the work of Greenberg (1978), (e.g., sixths). Consequently, the acquisition of clusters is Locke (1983) calculated that 39% had word-initial clusters one of the longest-lasting aspects of speech acquisition in only, 13% had final clusters only, and the remaining 48% normally developing children. -

Syllabic-Consonant Formation in Traditional New Mexico Spanish* Carlos-Eduardo Piñeros University of Iowa

Syllabic-Consonant Formation in Traditional New Mexico Spanish* Carlos-Eduardo Piñeros University of Iowa An interesting development in the phonology of Traditional New Mexico Spanish (TNMS)1 is the formation of syllabic consonants through the absorption of an adjacent vowel (e.g. [bo.n.t o] < [bo.ní.t o] ‘beautiful’). The effect of this process is that a syllable formerly headed by a vowel is now headed by a consonant. This sound change is quite unexpected given that under any version of the sonority scale, consonants are less sonorous than vowels. Since the nucleus is the peak of sonority within the syllable, one would expect the segment of higher sonority to be preferred in the role of syllable head; yet it is exactly in the opposite direction that the formation of syllabic consonants advances. In TNMS, an additional property of this process is that the nuclear vowels that are replaced by consonants are high vowels bearing primary or secondary stress. Moreover, among stressed high vowels, the ones that yield their syllabicity to an adjacent consonant are those that belong to affixes or function words. Using the framework of Optimality Theory (Prince and Smolensky 1993/2002), in this paper I develop an analysis of consonant syllabization in which the unexpected substitution of a vowel by a consonant as foot and syllable head is justified by a positional markedness constraint that bars the marked value on the place-of-articulation scale (e.g. Dorsal) from the position of foot DTE (Designated Terminal Element, in the terminology of Liberman 1975). Contrary to previous approaches that assume that vowel deletion is a condition for the syllabization of the consonant (Bell 1970/1979, Lispki 1993), I argue, following Coleman (2001) and Espinosa (1909/1930, 1925), that the vowel that disappears in 2 the process of syllabizing a consonant is not deleted but rather is either overlapped by that consonant or assimilated to it. -

Palatalization and Velarization in Malayalam Nasals: a Preliminary Acoustic Study of the Dental–Alveolar Contrast

Palatalization and velarization in Malayalam nasals: a preliminary acoustic study of the dental–alveolar contrast Sameer ud Dowla Khan Reed College [email protected] Abstract The current study builds upon the literature on secondary articulations inMalay- alam liquids to investigate whether another set of sonorants, i.e. the nasals, also involve palatalization, velarization, or varying configurations of the tongue root. Specifically, the current study focuses on the anterior nasals, i.e. dental n vs. alveo- lar n,̠ a marginal contrast which has not been examined phonetically for secondary articulations. What is known about these two nasals is that they stem from different historical sources, they contrast in precise place of articulation, and they have been described impressionistically as distinguishable by velarization on the dental n and palatalization on the alveolar n,̠ although no phonetic evidence has ever been pro- vided to support either claim. Preliminary acoustic results from a single speaker in the current study suggest that these claims are in fact borne out: back vowels are generally fronted when adjacent to geminate alveolar nn̠ ,̠ compared to those adja- cent to geminate dental nn. This suggests palatalization on the former and/or velar- ization on the latter, in line with the acoustic results for liquids in previous studies. These acoustic results thus suggest that Malayalam speakers can use secondary ar- ticulations to exaggerate the differences between otherwise very similar nasals, in the same ways that they use those articulations to distinguish the “clear” and “dark” classes of liquids. 1 Background Malayalam is famous for its large number of contrastive places of articulation (Mohanan & Mohanan (1984)), which extend not just to obstruents, which have strong place cues (Jun (2004)) in their formant transitions and especially the loud aperiodic noise in their burst and frication, but also to sonorants, which do not have strong place cues.