UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ GEMINATED LIQUIDS in JAPANESE: a PRODUCTION STUDY a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

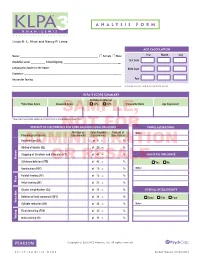

Sample, Not for Administration Or Resale

ANALYSIS FORM Linda M. L. Khan and Nancy P. Lewis Age Calculation Name: ______________________________________________________ u Female u Male Year Month Day Test Date Grade/Ed. Level: __________ School/Agency: __________________________________________ Language(s) Spoken in the Home: ___________________________________________________ Birth Date Examiner: ____________________________________________________________________ Reason for Testing: ______________________________________________________________ Age ____________________________________________________________________________ Reminder: Do not round up to next month or year. KLPA–3 Score Summary Confidence Interval *Total Raw Score Standard Score 90% 95% Percentile Rank Age Equivalent SAMPLE,– * Raw score equals total number of occurrences of scored phonological processes. Percent of OccurrenceNOT for Core Phonological ProcessesFOR Vowel Alterations Number of Total Possible Percent of Notes: Phonological Process Occurrences Occurrences Occurrences DeaffricationADMINISTRATION (DF) of 8 = % Gliding of liquids (GL) of 20 = % Stopping of fricatives and affricates (ST) of 48 = % Dialectal Influence Manner OR RESALE Stridency deletion (STR) of 42 = % Yes No Vocalization (VOC) of 15 = % Notes: Palatal fronting (PF) of 12 = % Place Velar fronting (VF) of 23 = % Cluster simplification (CS) of 23 = % Overall Intelligibility Deletion of final consonant (DFC) of 36 = % Good Fair Poor Reduction Syllable reduction (SR) of 25 = % Notes: Final devoicing (FDV) of 35 = % Voicing Initial voicing -

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin Essay Title: The sound system of Japanese This essay aims to introduce the sound system of Japanese, including the inventories of consonants, vowels, and diphthongs. The phonological variations of the sound segments in different phonetic environments are also included. For the illustration, word examples are given and they are presented in the following format: [IPA] (Romaji: “meaning”). Consonants In Japanese, there are 14 core consonants, and some of them have a lot of allophonic variations. The various types of consonants classified with respect to their manner of articulation are presented as follows. Stop Japanese has six oral stops or plosives, /p b t d k g/, which are classified into three place categories, bilabial, alveolar, and velar, as listed below. In each place category, there is a pair of plosives with the contrast in voicing. /p/ = a voiceless bilabial plosive [p]: [ippai] (ippai: “A cup of”) /b/ = a voiced bilabial plosive [b]: [baɴ] (ban: “Night”) /t/ = a voiceless alveolar plosive [t]: [oto̞ ːto̞ ] (ototo: “Brother”) /d/ = a voiced alveolar plosive [d]: [to̞ mo̞ datɕi] (tomodachi: “Friend”) /k/ = a voiceless velar plosive [k]: [kaiɰa] (kaiwa: “Conversation”) /g/ = a voiced velar plosive [g]: [ɡakɯβsai] (gakusai: “Student”) Phonetically, Japanese also has a glottal stop [ʔ] which is commonly produced to separate the neighboring vowels occurring in different syllables. This phonological phenomenon is known as ‘glottal stop insertion’. The glottal stop may be realized as a pause, which is used to indicate the beginning or the end of an utterance. For instance, the word “Japanese money” is actually pronounced as [ʔe̞ ɴ], instead of [je̞ ɴ], and the pronunciation of “¥15” is [dʑɯβːɡo̞ ʔe̞ ɴ]. -

D Igital Text

Digital text The joys of character sets Contents Storing text ¡ General problems ¡ Legacy character encodings ¡ Unicode ¡ Markup languages Using text ¡ Processing and display ¡ Programming languages A little bit about writing systems Overview Latin Cyrillic Devanagari − − − − − − Tibetan \ / / Gujarati | \ / − Armenian / Bengali SOGDIAN − Mongolian \ / / Gurumukhi SCRIPT Greek − Georgian / Oriya Chinese | / / | / Telugu / PHOENICIAN BRAHMI − − Kannada SINITIC − Japanese SCRIPT \ SCRIPT Malayalam SCRIPT \ / | \ \ Tamil \ Hebrew | Arabic \ Korean | \ \ − − Sinhala | \ \ | \ \ _ _ Burmese | \ \ Khmer | \ \ Ethiopic Thaana \ _ _ Thai Lao The easy ones Latin is the alphabet and writing system used in the West and some other places Greek and Cyrillic (Russian) are very similar, they just use different characters Armenian and Georgian are also relatively similar More difficult Hebrew is written from right−to−left, but numbers go left−to−right... Arabic has the same rules, but also requires variant selection depending on context and ligature forming The far east Chinese uses two ’alphabets’: hanzi ideographs and zhuyin syllables Japanese mixes four alphabets: kanji ideographs, katakana and hiragana syllables and romaji (latin) letters and numbers Korean uses hangul ideographs, combined from jamo components Vietnamese uses latin letters... The Indic languages Based on syllabic alphabets Require complex ligature forming Letters are not written in logical order, but require a strange ’circular’ ordering In addition, a single line consists of separate -

AIX Globalization

AIX Version 7.1 AIX globalization IBM Note Before using this information and the product it supports, read the information in “Notices” on page 233 . This edition applies to AIX Version 7.1 and to all subsequent releases and modifications until otherwise indicated in new editions. © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 2010, 2018. US Government Users Restricted Rights – Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents About this document............................................................................................vii Highlighting.................................................................................................................................................vii Case-sensitivity in AIX................................................................................................................................vii ISO 9000.....................................................................................................................................................vii AIX globalization...................................................................................................1 What's new...................................................................................................................................................1 Separation of messages from programs..................................................................................................... 1 Conversion between code sets............................................................................................................. -

Frank's Do-It-Yourself Kana Cards V

Frank's do-it-yourself kana cards v. 1.0, 2000-08-07 Frank Stajano University of Cambridge and AT&T Laboratories Cambridge http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~fms27/ and http://www.uk.research.att.com/~fms/ This set of flash cards is meant to help you familiar cards and insist on the difficult part of き and さ with a separate stroke, become fluent in the use of the Japanese ones. unlike what happens in the fonts used in hiragana and katakana syllabaries. I made this document. I have followed the stroke it because I needed one myself and could The complete set consists of 10 double- counts of Henshall-Takagaki, even when not find it in the local bookshops (kanji sided sheets (20 printable pages) of 50 they seem weird for the shape of the char- cards were available, and I bought those; cards each, but you may choose to print acter as drawn on the card. but kana cards weren't); if it helps you too, smaller subsets as detailed below. Actu- so much the better. ally there are some blanks, so the total The easiest way to turn this document into number of cards is only 428 instead of 500. a set of cards is simply to print it (double The romanisation system chosen for these It would have been possible to fit them on sided of course!) and then cut each page cards is the Hepburn, which is the most 9 sheets instead of 10, but only by com- into cards with a ruler and a sharp blade. -

International Language Environments Guide

International Language Environments Guide Sun Microsystems, Inc. 4150 Network Circle Santa Clara, CA 95054 U.S.A. Part No: 806–6642–10 May, 2002 Copyright 2002 Sun Microsystems, Inc. 4150 Network Circle, Santa Clara, CA 95054 U.S.A. All rights reserved. This product or document is protected by copyright and distributed under licenses restricting its use, copying, distribution, and decompilation. No part of this product or document may be reproduced in any form by any means without prior written authorization of Sun and its licensors, if any. Third-party software, including font technology, is copyrighted and licensed from Sun suppliers. Parts of the product may be derived from Berkeley BSD systems, licensed from the University of California. UNIX is a registered trademark in the U.S. and other countries, exclusively licensed through X/Open Company, Ltd. Sun, Sun Microsystems, the Sun logo, docs.sun.com, AnswerBook, AnswerBook2, Java, XView, ToolTalk, Solstice AdminTools, SunVideo and Solaris are trademarks, registered trademarks, or service marks of Sun Microsystems, Inc. in the U.S. and other countries. All SPARC trademarks are used under license and are trademarks or registered trademarks of SPARC International, Inc. in the U.S. and other countries. Products bearing SPARC trademarks are based upon an architecture developed by Sun Microsystems, Inc. SunOS, Solaris, X11, SPARC, UNIX, PostScript, OpenWindows, AnswerBook, SunExpress, SPARCprinter, JumpStart, Xlib The OPEN LOOK and Sun™ Graphical User Interface was developed by Sun Microsystems, Inc. for its users and licensees. Sun acknowledges the pioneering efforts of Xerox in researching and developing the concept of visual or graphical user interfaces for the computer industry. -

Introduction to the Special Issue on Japanese Geminate Obstruents

J East Asian Linguist (2013) 22:303-306 DOI 10.1007/s10831-013-9109-z Introduction to the special issue on Japanese geminate obstruents Haruo Kubozono Received: 8 January 2013 / Accepted: 22 January 2013 / Published online: 6 July 2013 © Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2013 Geminate obstruents (GOs) and so-called unaccented words are the two properties most characteristic of Japanese phonology and the two features that are most difficult to learn for foreign learners of Japanese, regardless of their native language. This special issue deals with the first of these features, discussing what makes GOs so difficult to master, what is so special about them, and what makes the research thereon so interesting. GOs are one of the two types of geminate consonant in Japanese1 which roughly corresponds to what is called ‘sokuon’ (促音). ‘Sokon’ is defined as a ‘one-mora- long silence’ (Sanseido Daijirin Dictionary), often symbolized as /Q/ in Japanese linguistics, and is transcribed with a small letter corresponding to /tu/ (っ or ッ)in Japanese orthography. Its presence or absence is distinctive in Japanese phonology as exemplified by many pairs of words, including the following (dots /. / indicate syllable boundaries). (1) sa.ki ‘point’ vs. sak.ki ‘a short time ago’ ka.ko ‘past’ vs. kak.ko ‘paranthesis’ ba.gu ‘bug (in computer)’ vs. bag.gu ‘bag’ ka.ta ‘type’ vs. kat.ta ‘bought (past tense of ‘buy’)’ to.sa ‘Tosa (place name)’ vs. tos.sa ‘in an instant’ More importantly, ‘sokuon’ is an important characteristic of Japanese speech rhythm known as mora-timing. It is one of the four elements that can form a mora 1 The other type of geminate consonant is geminate nasals, which phonologically consist of a coda nasal and the nasal onset of the following syllable, e.g., /am. -

RP Basic Series Installation Documents

BAS System Note: Lighting control system furnished by Division 25 (Controls Contractor) and installed by Division 26. BACnet: CL3P 22/2 Shielded, Low Cap, Max 4,000' Station/Satellite Network: CL3P 22/4, Max 500' IP Network: CAT-5e, Max 328' T BACnet MS/TP Network Terminator LEVEL-3 T Star Station/Satellite Network Terminator BACnet Router RIXX-00 RKX-XX RPDSXX-XX MSTP T CTS1RL-XX NAME ADDR: 0 IP: XXX.XXX.XX.XX (TYPICAL 2) LOCATION T SCUI8-00 SCAO8-00 CTS1CH-XX ADDR: 1 T T NAME NAME NAME ADDR: XX ADDR: XX ADDR: XX NAME NAME CTS1CH-XX LOCATION LOCATION LOCATION SLOT: 1 SLOT: 2 LOCATION LOCATION ADDR: 2 T BAS NETWORK LEVEL-2 T-Tap BACnet Router RPSSXX-XX RPDSXX-XX MSTP T NAME IP: XXX.XXX.XX.XX LOCATION ZCSS-00-00 CS1 SCSS-00 SCSS-00 SCAO8-00 CTS4CH-XX CTS6CH-XX CTS1CH-XX CTS2CH-XX CTS1RL-XX CTS3CH-XX T ADDR: 0 ADDR: 1 T ADDR: 0 ADDR: 1 T T ADDR: 0 ADDR: 1 NAME T T NAME T T T T NAME T T T ADDR: XX ADDR: XX NAME NAME ADDR: XX NAME LOCATION LOCATION SLOT: 1 SLOT: 2 LOCATION SLOT:1 LOCATION LOCATION LOCATION LEVEL-1 Daisy Chain BACnet Router MSTP T ZCDS-00-00 NAME CS1 SCSS-00 SCDS-00 SCDS-00 IP: XXX.XXX.XX.XX Engineering Standards SYS_01.00 LOCATION 1 1 4 CTS2RL-XX CTS1RL-XX CTS1CH-XX CTS2CH-XX CTS3PR-XX 2 CTS6PR-XX 2 5 T T ADDR: 0 ADDR: 1 ADDR: 2 ADDR: 3 ADDR: 4 3 ADDR: 5 3 6 Lighting Control System Riser NAME T ADDR:XX NAME NAME NAME Rev: 4 Type: Reference Date: 01-20-15 Job #: LOCATION SLOT: 1 SLOT: 2 SLOT: 3 LOCATION LOCATION LOCATION Engineered: WCD Drawn: NB Checked: 1 of 1 Tech Note 071014_02 Date: July 10, 2014 Product: TK-2.0 Subject: USB Cable and Driver Installation Note: Recommended USB Installation Procedure 1. -

A Case Study of Norwegian Clusters

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title Morphological derived-environment effects in gestural coordination: A case study of Norwegian clusters Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5mn3w7gz Journal Lingua, 117 ISSN 0024-3841 Author Bradley, Travis G. Publication Date 2007-06-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Bradley, Travis G. 2007. Morphological Derived-Environment Effects in Gestural Coordination: A Case Study of Norwegian Clusters. Lingua 117.6:950-985. Morphological derived-environment effects in gestural coordination: a case study of Norwegian clusters Travis G. Bradley* Department of Spanish and Classics, University of California, 705 Sproul Hall, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616, USA Abstract This paper examines morphophonological alternations involving apicoalveolar tap- consonant clusters in Urban East Norwegian from the framework of gestural Optimality Theory. Articulatory Phonology provides an insightful explanation of patterns of vowel intrusion, coalescence, and rhotic deletion in terms of the temporal coordination of consonantal gestures, which interacts with both prosodic and morphological structure. An alignment-based account of derived-environment effects is proposed in which complete overlap in rhotic-consonant clusters is blocked within morphemes but not across morpheme or word boundaries. Alignment constraints on gestural coordination also play a role in phonologically conditioned allomorphy. The gestural analysis is contrasted with alternative Optimality-theoretic accounts. Furthermore, it is argued that models of the phonetics-phonology interface which view timing as a low-level detail of phonetic implementation incorrectly predict that input morphological structure should have no effect on gestural coordination. The patterning of rhotic-consonant clusters in Norwegian is consistent with a model that includes gestural representations and constraints directly in the phonological grammar, where underlying morphological structure is still visible. -

Introduction to Japanese Computational Linguistics Francis Bond and Timothy Baldwin

1 Introduction to Japanese Computational Linguistics Francis Bond and Timothy Baldwin The purpose of this chapter is to provide a brief introduction to the Japanese language, and natural language processing (NLP) research on Japanese. For a more complete but accessible description of the Japanese language, we refer the reader to Shibatani (1990), Backhouse (1993), Tsujimura (2006), Yamaguchi (2007), and Iwasaki (2013). 1 A Basic Introduction to the Japanese Language Japanese is the official language of Japan, and belongs to the Japanese language family (Gordon, Jr., 2005).1 The first-language speaker pop- ulation of Japanese is around 120 million, based almost exclusively in Japan. The official version of Japanese, e.g. used in official settings andby the media, is called hyōjuNgo “standard language”, but Japanese also has a large number of distinctive regional dialects. Other than lexical distinctions, common features distinguishing Japanese dialects are case markers, discourse connectives and verb endings (Kokuritsu Kokugo Kenkyujyo, 1989–2006). 1There are a number of other languages in the Japanese language family of Ryukyuan type, spoken in the islands of Okinawa. Other languages native to Japan are Ainu (an isolated language spoken in northern Japan, and now almost extinct: Shibatani (1990)) and Japanese Sign Language. Readings in Japanese Natural Language Processing. Francis Bond, Timothy Baldwin, Kentaro Inui, Shun Ishizaki, Hiroshi Nakagawa and Akira Shimazu (eds.). Copyright © 2016, CSLI Publications. 1 Preview 2 / Francis Bond and Timothy Baldwin 2 The Sound System Japanese has a relatively simple sound system, made up of 5 vowel phonemes (/a/,2 /i/, /u/, /e/ and /o/), 9 unvoiced consonant phonemes (/k/, /s/,3 /t/,4 /n/, /h/,5 /m/, /j/, /ó/ and /w/), 4 voiced conso- nants (/g/, /z/,6 /d/ 7 and /b/), and one semi-voiced consonant (/p/). -

Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera U Osijeku Filozofski Fakultet U Osijeku Odsjek Za Engleski Jezik I Književnost Uroš Ba

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Croatian Digital Thesis Repository Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet u Osijeku Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Uroš Barjaktarević Japanese-English Language Contact / Japansko-engleski jezični kontakt Diplomski rad Kolegij: Engleski jezik u kontaktu Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Dubravka Vidaković Erdeljić Osijek, 2015. 1 Summary JAPANESE-ENGLISH LANGUAGE CONTACT The paper examines the language contact between Japanese and English. The first section of the paper defines language contact and the most common contact-induced language phenomena with an emphasis on linguistic borrowing as the dominant contact-induced phenomenon. The classification of linguistic borrowing thereby follows Haugen's distinction between morphemic importation and substitution. The second section of the paper presents the features of the Japanese language in terms of origin, phonology, syntax, morphology, and writing. The third section looks at the history of language contact of the Japanese with the Europeans, starting with the Portuguese and Spaniards, followed by the Dutch, and finally the English. The same section examines three different borrowing routes from English, and contact-induced language phenomena other than linguistic borrowing – bilingualism , code alternation, code-switching, negotiation, and language shift – present in Japanese-English language contact to varying degrees. This section also includes a survey of the motivation and reasons for borrowing from English, as well as the attitudes of native Japanese speakers to these borrowings. The fourth and the central section of the paper looks at the phenomenon of linguistic borrowing, its scope and the various adaptations that occur upon morphemic importation on the phonological, morphological, orthographic, semantic and syntactic levels. -

Hiragana and Katakana Worksheets Free

201608 Hiragana and Katakana worksheets ひらがな カタカナ 1. Three types of letters ··········································· 1 _ 2. Roma-ji, Hiragana and Katakana ·························· 2 3. Hiragana worksheets and quizzes ························ 3-9 4. The rules in Hiragana···································· 10-11 5. The rules in Katakana ········································ 12 6. Katakana worksheets and quizzes ··················· 12-22 Japanese Language School, Tokyo, Japan Meguro Language Center TEL.: 03-3493-3727 Email: [email protected] http://www.mlcjapanese.co.jp Meguro Language Center There are three types of letters in Japanese. 1. Hiragana (phonetic sounds) are basically used for particles, words and parts of words. 2. Katakana (phonetic sounds) are basically used for foreign/loan words. 3. Kanji (Chinese characters) are used for the stem of words and convey the meaning as well as sound. Hiragana is basically used to express 46 different sounds used in the Japanese language. We suggest you start learning Hiragana, then Katakana and then Kanji. If you learn Hiragana first, it will be easier to learn Katakana next. Hiragana will help you learn Japanese pronunciation properly, read Japanese beginners' textbooks and write sentences in Japanese. Japanese will become a lot easier to study after having learned Hiragana. Also, as you will be able to write sentences in Japanese, you will be able to write E-mails in Hiragana. Katakana will help you read Japanese menus at restaurants. Hiragana and Katakana will be a good help to your Japanese study and confortable living in Japan. To master Hiragana, it is important to practice writing Hiragana. Revision is also very important - please go over what you have learned several times.