前書き | Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Study of Old Documents of Hokkaido and Kuril Ainu

NINJAL International Symposium 2018 Approaches to Endangered Languages in Japan and Northeast Asia, August 6-8 The study of old documents of Hokkaido and Kuril Ainu: Promise and Challenges Tomomi Sato (Hokkaido U) & Anna Bugaeva (TUS/NINJAL) [email protected] [email protected]) Introduction: Ainu • AINU (isolate, North Japan, moribund) • Is the only non-Japonic lang. of Japan. • Major dialect groups : Hokkaido (moribund), Sakhalin (extinct since 1993), Kuril (extinct since the end of XIX). • Was also spoken in Tōhoku till mid XVIII. • Hokkaido Ainu dialects: Southwestern (well documented) Northeastern (less documented) • Is not used in daily conversation since the 1950s. • Ethnical Ainu: 100,000. 2 Fig. 2 Major language families in Northeast Asia (excluding Sinitic) Amuric Mongolic Tungusic Ainuic Koreanic Japonic • Ainu shares only few features with Northeast Asian languages. • Ainu is typologically “more like a morphologically reduced version of a North American language.” (Johanna Nichols p.c.). • This is due to the strongly head-marking character of Ainu (Bugaeva, to appear). Why is it important to study Ainu? • Ainu culture is widely regarded as a direct descendant of the Jōmon culture which was spread in the Japanese archipelago in the Prehistoric time from about 14,000 BC. • Ainu is the only surviving Jōmon language; there had been other Jōmon lgs too: about 300 lgs (Janhunen 2002), cf. 10 lgs (Whitman, p.c.) . • Ainu is likely to be much more typical of what languages were like in Northeast Asia several millennia ago than the picture we would get from Chinese, Japanese or Korean. • Focusing on Ainu can help us understand a period of northeast Asian history when political, cultural and linguistic units were very different to what they have been since the rise of the great historically-attested states of East Asia. -

Man'yogana.Pdf (574.0Kb)

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO Additional services for Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The origin of man'yogana John R. BENTLEY Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies / Volume 64 / Issue 01 / February 2001, pp 59 73 DOI: 10.1017/S0041977X01000040, Published online: 18 April 2001 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0041977X01000040 How to cite this article: John R. BENTLEY (2001). The origin of man'yogana. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 64, pp 5973 doi:10.1017/S0041977X01000040 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO, IP address: 131.156.159.213 on 05 Mar 2013 The origin of man'yo:gana1 . Northern Illinois University 1. Introduction2 The origin of man'yo:gana, the phonetic writing system used by the Japanese who originally had no script, is shrouded in mystery and myth. There is even a tradition that prior to the importation of Chinese script, the Japanese had a native script of their own, known as jindai moji ( , age of the gods script). Christopher Seeley (1991: 3) suggests that by the late thirteenth century, Shoku nihongi, a compilation of various earlier commentaries on Nihon shoki (Japan's first official historical record, 720 ..), circulated the idea that Yamato3 had written script from the age of the gods, a mythical period when the deity Susanoo was believed by the Japanese court to have composed Japan's first poem, and the Sun goddess declared her son would rule the land below. -

Reading the Miraculous Powers of Japanese Poetry Spells, Truth Acts, and a Medieval Buddhist Poetics of the Supernatural

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 32/: –33 © 2005 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture R. Keller Kimbrough Reading the Miraculous Powers of Japanese Poetry Spells, Truth Acts, and a Medieval Buddhist Poetics of the Supernatural The supernatural powers of Japanese poetry are widely documented in the lit- erature of Heian and medieval Japan. Twentieth-century scholars have tended to follow Orikuchi Shinobu in interpreting and discussing miraculous verses in terms of ancient (arguably pre-Buddhist and pre-historical) beliefs in koto- dama 言霊, “the magic spirit power of special words.” In this paper, I argue for the application of a more contemporaneous hermeneutical approach to the miraculous poem-stories of late-Heian and medieval Japan: thirteenth- century Japanese “dharani theory,” according to which Japanese poetry is capable of supernatural effects because, as the dharani of Japan, it contains “reason” or “truth” (kotowari) in a semantic superabundance. In the first sec- tion of this article I discuss “dharani theory” as it is articulated in a number of Kamakura- and Muromachi-period sources; in the second, I apply that the- ory to several Heian and medieval rainmaking poem-tales; and in the third, I argue for a possible connection between the magico-religious technology of Indian “Truth Acts” (saccakiriyā, satyakriyā), imported to Japan in various sutras and sutra commentaries, and some of the miraculous poems of the late- Heian and medieval periods. keywords: waka – dharani – kotodama – katoku setsuwa – rainmaking – Truth Act – saccakiriyā, satyakriyā R. Keller Kimbrough is an Assistant Professor of Japanese at Colby College. In the 2005– 2006 academic year, he will be a Visiting Research Fellow at the Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture. -

SUPPORTING the CHINESE, JAPANESE, and KOREAN LANGUAGES in the OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM by Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT the Asian L

SUPPORTING THE CHINESE, JAPANESE, AND KOREAN LANGUAGES IN THE OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM By Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT The Asian language versions of the OpenVMS operating system allow Asian-speaking users to interact with the OpenVMS system in their native languages and provide a platform for developing Asian applications. Since the OpenVMS variants must be able to handle multibyte character sets, the requirements for the internal representation, input, and output differ considerably from those for the standard English version. A review of the Japanese, Chinese, and Korean writing systems and character set standards provides the context for a discussion of the features of the Asian OpenVMS variants. The localization approach adopted in developing these Asian variants was shaped by business and engineering constraints; issues related to this approach are presented. INTRODUCTION The OpenVMS operating system was designed in an era when English was the only language supported in computer systems. The Digital Command Language (DCL) commands and utilities, system help and message texts, run-time libraries and system services, and names of system objects such as file names and user names all assume English text encoded in the 7-bit American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) character set. As Digital's business began to expand into markets where common end users are non-English speaking, the requirement for the OpenVMS system to support languages other than English became inevitable. In contrast to the migration to support single-byte, 8-bit European characters, OpenVMS localization efforts to support the Asian languages, namely Japanese, Chinese, and Korean, must deal with a more complex issue, i.e., the handling of multibyte character sets. -

Problematika České Transkripce Japonštiny a Pravidla Jejího Užívání Nihongo 日本語 社会 Šakai Fudži 富士 Ivona Barešová, Monika Dytrtová Momidži Tókjó もみ じ 東京 Čotto ち ょっ と

チェ コ語 翼 čekogo cubasa šin’jó 信用 Problematika české transkripce japonštiny a pravidla jejího užívání nihongo 日本語 社会 šakai Fudži 富士 Ivona Barešová, Monika Dytrtová momidži Tókjó もみ じ 東京 čotto ち ょっ と PROBLEMATIKA ČESKÉ TRANSKRIPCE JAPONŠTINY A PRAVIDLA JEJÍHO UŽÍVÁNÍ Ivona Barešová Monika Dytrtová Spolupracovala: Bc. Mária Ševčíková Oponenti: prof. Zdeňka Švarcová, Dr. Mgr. Jiří Matela, M.A. Tento výzkum byl umožněn díky účelové podpoře na specifi cký vysokoškolský výzkum udělené roku 2013 Univerzitě Palackého v Olomouci Ministerstvem školství, mládeže a tělovýchovy ČR (FF_2013_044). Neoprávněné užití tohoto díla je porušením autorských práv a může zakládat občanskoprávní, správněprávní, popř. trestněprávní odpovědnost. 1. vydání © Ivona Barešová, Monika Dytrtová, 2014 © Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci, 2014 ISBN 978-80-244-4017-0 Ediční poznámka V publikaci je pro přepis japonských slov užito české transkripce, s výjimkou jejich výskytu v anglic kém textu, kde se objevuje původní transkripce anglická. Japonská jména jsou uváděna v pořadí jméno – příjmení, s výjimkou jejich uvedení v bibliogra- fi ckých citacích, kde se jejich pořadí řídí citační normou. Pokud není uvedeno jinak, autorkami překladů citací a parafrází jsou autorky této práce. V textu jsou použity následující grafi cké prostředky. Fonologický zápis je uveden standardně v šikmých závorkách // a fonetický v hranatých []. Fonetické symboly dle IPA jsou použity v rámci kapi toly 5. V případě, že není nutné zaznamenávat jemné zvukové nuance dané hlásky nebo že není kladen důraz na zvukové rozdíly mezi jed- notlivými hláskami, je jinde v textu, kde je to možné, z důvodu usnadnění porozumění užito namísto těchto specifi ckých fonetických symbolů písmen české abecedy, např. -

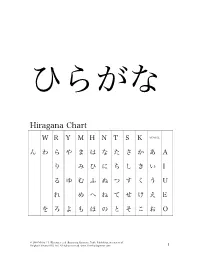

Hiragana Chart

ひらがな Hiragana Chart W R Y M H N T S K VOWEL ん わ ら や ま は な た さ か あ A り み ひ に ち し き い I る ゆ む ふ ぬ つ す く う U れ め へ ね て せ け え E を ろ よ も ほ の と そ こ お O © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 1 Beginning Japanese 名前: ________________________ 1-1 Hiragana Activity Book 日付: ___月 ___日 一、 Practice: あいうえお かきくけこ がぎぐげご O E U I A お え う い あ あ お え う い あ お う あ え い あ お え う い お う い あ お え あ KO KE KU KI KA こ け く き か か こ け く き か こ け く く き か か こ き き か こ こ け か け く く き き こ け か © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 2 GO GE GU GI GA ご げ ぐ ぎ が が ご げ ぐ ぎ が ご ご げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ が が ご げ ぎ が ご ご げ が げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ ご げ が 二、 Fill in each blank with the correct HIRAGANA. SE N SE I KI A RA NA MA E 1. -

Handy Katakana Workbook.Pdf

First Edition HANDY KATAKANA WORKBOOK An Introduction to Japanese Writing: KANA THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT FOR BEGINNING LEVEL JAPANESE LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION. \ FrF!' '---~---- , - Y. M. Shimazu, Ed.D. -----~---- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENlS vii STUDYSHEET#l 1 A,I,U,E, 0, KA,I<I, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #1 2 PRACTICE: A, I,U, E, 0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU, GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #2 3 MORE PRACTICE: A, I, U, E,0, KA,KI,KU, KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #~3 4 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: A,I,U, E,0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N STUDYSHEET #2 5 SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI,ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #4 6 PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, 'lSU,TE,TO, OA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #5 7 MORE PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE,SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE, W, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORKSHEET #6 8 ADDmONAL PRACI'ICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI,TSU,TE,TO, DA, DE,DO STUDYSHEET #3 9 NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE, HO, BA, BI,BU,BE,BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #7 10 PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE,HO, BA,BI, BU,BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #8 11 MORE PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA,HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,BU,BE, BO, PA,PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #9 12 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,3U, BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO STUDYSHEET #4 13 MA, MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET#10 14 PRACTICE: MA,MI, MU,ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #11 15 MORE PRACTICE: MA, MI,MU,ME,MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #12 16 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: MA,MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO STUDYSHEET #5 17 -

A Student Model of Katakana Reading Proficiency for a Japanese Language Intelligent Tutoring System

A Student Model of Katakana Reading Proficiency for a Japanese Language Intelligent Tutoring System Anthony A. Maciejewski Yun-Sun Kang School of Electrical Engineering Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana 47907 Abstract--Thls work describes the development of a kanji. Due to the limited number of kana, their relatively low student model that Is used In a Japanese language visual complexity, and their systematic arrangement they do Intelligent tutoring system to assess a pupil's not represent a significant barrier to the student of Japanese. proficiency at reading one of the distinct In fact, the relatively small effort required to learn katakana orthographies of Japanese, known as k a t a k a n a , yields significant returns to readers of technical Japanese due to While the effort required to memorize the relatively the high incidence of terms derived from English and few k a t a k a n a symbols and their associated transliterated into katakana. pronunciations Is not prohibitive, a major difficulty In reading katakana Is associated with the phonetic This work describes the development of a system that is modifications which occur when English words used to automatically acquire knowledge about how English which are transliterated Into katakana are made to words are transliterated into katakana and then to use that conform to the more restrictive rules of Japanese information in developing a model of a student's proficiency in phonology. The algorithm described here Is able to reading katakana. This model is used to guide the instruction automatically acquire a knowledge base of these of the student using an intelligent tutoring system developed phonological transformation rules, use them to previously [6,8]. -

Chinese Script Generation Panel Document

Chinese Script Generation Panel Document Proposal for the Generation Panel for the Chinese Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone 1. General Information Chinese script is the logograms used in the writing of Chinese and some other Asian languages. They are called Hanzi in Chinese, Kanji in Japanese and Hanja in Korean. Since the Hanzi unification in the Qin dynasty (221-207 B.C.), the most important change in the Chinese Hanzi occurred in the middle of the 20th century when more than two thousand Simplified characters were introduced as official forms in Mainland China. As a result, the Chinese language has two writing systems: Simplified Chinese (SC) and Traditional Chinese (TC). Both systems are expressed using different subsets under the Unicode definition of the same Han script. The two writing systems use SC and TC respectively while sharing a large common “unchanged” Hanzi subset that occupies around 60% in contemporary use. The common “unchanged” Hanzi subset enables a simplified Chinese user to understand texts written in traditional Chinese with little difficulty and vice versa. The Hanzi in SC and TC have the same meaning and the same pronunciation and are typical variants. The Japanese kanji were adopted for recording the Japanese language from the 5th century AD. Chinese words borrowed into Japanese could be written with Chinese characters, while Japanese words could be written using the character for a Chinese word of similar meaning. Finally, in Japanese, all three scripts (kanji, and the hiragana and katakana syllabaries) are used as main scripts. The Chinese script spread to Korea together with Buddhism from the 2nd century BC to the 5th century AD. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Simplification of Chinese Characters in Japan and China

CONTRASTING APPROACHES TO CHINESE CHARACTER REFORM: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIMPLIFICATION OF CHINESE CHARACTERS IN JAPAN AND CHINA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIAN STUDIES AUGUST 2012 By Kei Imafuku Thesis Committee: Alexander Vovin, Chairperson Robert Huey Dina Rudolph Yoshimi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express deep gratitude to Alexander Vovin, Robert Huey, and Dina R. Yoshimi for their Japanese and Chinese expertise and kind encouragement throughout the writing of this thesis. Their guidance, as well as the support of the Center for Japanese Studies, School of Pacific and Asian Studies, and the East-West Center, has been invaluable. i ABSTRACT Due to the complexity and number of Chinese characters used in Chinese and Japanese, some characters were the target of simplification reforms. However, Japanese and Chinese simplifications frequently differed, resulting in the existence of multiple forms of the same character being used in different places. This study investigates the differences between the Japanese and Chinese simplifications and the effects of the simplification techniques implemented by each side. The more conservative Japanese simplifications were achieved by instating simpler historical character variants while the more radical Chinese simplifications were achieved primarily through the use of whole cursive script forms and phonetic simplification techniques. These techniques, however, have been criticized for their detrimental effects on character recognition, semantic and phonetic clarity, and consistency – issues less present with the Japanese approach. By comparing the Japanese and Chinese simplification techniques, this study seeks to determine the characteristics of more effective, less controversial Chinese character simplifications. -

The Japanese Writing Systems, Script Reforms and the Eradication of the Kanji Writing System: Native Speakers’ Views Lovisa Österman

The Japanese writing systems, script reforms and the eradication of the Kanji writing system: native speakers’ views Lovisa Österman Lund University, Centre for Languages and Literature Bachelor’s Thesis Japanese B.A. Course (JAPK11 Spring term 2018) Supervisor: Shinichiro Ishihara Abstract This study aims to deduce what Japanese native speakers think of the Japanese writing systems, and in particular what native speakers’ opinions are concerning Kanji, the logographic writing system which consists of Chinese characters. The Japanese written language has something that most languages do not; namely a total of three writing systems. First, there is the Kana writing system, which consists of the two syllabaries: Hiragana and Katakana. The two syllabaries essentially figure the same way, but are used for different purposes. Secondly, there is the Rōmaji writing system, which is Japanese written using latin letters. And finally, there is the Kanji writing system. Learning this is often at first an exhausting task, because not only must one learn the two phonematic writing systems (Hiragana and Katakana), but to be able to properly read and write in Japanese, one should also learn how to read and write a great amount of logographic signs; namely the Kanji. For example, to be able to read and understand books or newspaper without using any aiding tools such as dictionaries, one would need to have learned the 2136 Jōyō Kanji (regular-use Chinese characters). With the twentieth century’s progress in technology, comparing with twenty years ago, in this day and age one could probably theoretically get by alright without knowing how to write Kanji by hand, seeing as we are writing less and less by hand and more by technological devices. -

Na Kana Magiti Kei Na Lotu

1 NA KANA MAGITI KEI NA LOTU (Vola Tabu : Maciu 22:1-10; Luke 14:12-24) Vola ko Rev. Dr. Ilaitia S. Tuwere. Sa inaki ni vunau oqo me taroga ka sauma talega na taro : A cava na Lotu? Ni da tekivu edaidai ena noda solevu vakalotu, sa na yaga meda taroga ka tovolea talega me sauma na taro oqori. Ia, ena levu na kena isau eda na solia, me vaka na: gumatuataki ni masu kei na vulici ni Vola Tabu, bula vakayalo, muria na ivakarau se lawa ni lotu ka vuqa tale. Na veika oqori era ka dina ka tu kina eso na isau ni taro : A Cava na Lotu. Na i Vola Tabu e sega ni tuvalaka vakavosa vei keda na ibalebale ni lotu. E vakavuqa me boroya vei keda na iyaloyalo me vakadewataka kina na veika eso e vinakata me tukuna. E sega talega ni solia e duabulu ga na iyaloyalo me baleta na lotu. E vuqa sara e solia vei keda. Oqori me vaka na Qele ni Sipi kei na i Vakatawa Vinaka; na Vuni Vaini kei na Tabana; na i Vakavuvuli kei iratou na nona Gonevuli se Tisaipeli, na Masima se Rarama kei Vuravura, na Ulu kei na Vo ni Yago taucoko, ka vuqa tale. Ena mataka edaidai, meda raica vata yani na iyaloyalo ni kana magiti. E rua na kena ivakamacala eda rogoca, mai na Kosipeli i Maciu kei na nei Luke. Na kana magiti se na solevu edua na ivakarau vakaitaukei. Eda soqoni vata kina vakaveiwekani ena noda veikidavaki kei na marau, kena veitalanoa, kena sere kei na meke, kena salusalu kei na kumuni iyau.