The Japanese Writing Systems, Script Reforms and the Eradication of the Kanji Writing System: Native Speakers’ Views Lovisa Österman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tokyo: the Birth of an Imperial Capital

1 Ben-Ami Shillony Tokyo: The Birth of an Imperial Capital Ben-Ami Shillony Introduction By the middle of the nineteenth century Edo was the political, military and administrative capital of Japan, the largest city in the country, one of the largest cities in the world, and the seat of the shogun and his government. Nevertheless, until 1868 it had never been an imperial capital, the city in which the emperor resides. In the seventh century, when Japan adopted the Chinese model of a capital, the first imperial capital, Fujiwara, lasted for only 16 years, from 694 until 710. The second imperial capital, Nara, lasted for 74 years, from 710 until 784. The third capital, Nagaoka, lasted for only 10 years, from 784 until 794. But then the fourth capital, Heian-kyō (Kyoto), lasted for more than a thousand years, from 794 until 1868. During this long period, the emperors stayed in Kyoto, despite the fact that from the twelfth century political power shifted to the shoguns and the samurai class, and for almost half of that time the wielders of real power resided in the eastern part of Japan, in Kamakura and later in Edo. No one of the military rulers tried to move the emperor out of Kyoto to the place where they resided. Kyoto remained the "capital" (miyako) although its primacy was only nominal. The imperial palace stayed in Kyoto even when the city was torn by internal warfare and the palace was impoverished. Going to Kyoto was all the time called "going up" (noboru) and going from Kyoto was all the time called "going down" (sagaru). -

Neural Substrates of Hanja (Logogram) and Hangul (Phonogram) Character Readings by Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Neuroscience http://dx.doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2014.29.10.1416 • J Korean Med Sci 2014; 29: 1416-1424 Neural Substrates of Hanja (Logogram) and Hangul (Phonogram) Character Readings by Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Zang-Hee Cho,1 Nambeom Kim,1 The two basic scripts of the Korean writing system, Hanja (the logography of the traditional Sungbong Bae,2 Je-Geun Chi,1 Korean character) and Hangul (the more newer Korean alphabet), have been used together Chan-Woong Park,1 Seiji Ogawa,1,3 since the 14th century. While Hanja character has its own morphemic base, Hangul being and Young-Bo Kim1 purely phonemic without morphemic base. These two, therefore, have substantially different outcomes as a language as well as different neural responses. Based on these 1Neuroscience Research Institute, Gachon University, Incheon, Korea; 2Department of linguistic differences between Hanja and Hangul, we have launched two studies; first was Psychology, Yeungnam University, Kyongsan, Korea; to find differences in cortical activation when it is stimulated by Hanja and Hangul reading 3Kansei Fukushi Research Institute, Tohoku Fukushi to support the much discussed dual-route hypothesis of logographic and phonological University, Sendai, Japan routes in the brain by fMRI (Experiment 1). The second objective was to evaluate how Received: 14 February 2014 Hanja and Hangul affect comprehension, therefore, recognition memory, specifically the Accepted: 5 July 2014 effects of semantic transparency and morphemic clarity on memory consolidation and then related cortical activations, using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) Address for Correspondence: (Experiment 2). The first fMRI experiment indicated relatively large areas of the brain are Young-Bo Kim, MD Department of Neuroscience and Neurosurgery, Gachon activated by Hanja reading compared to Hangul reading. -

Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 a Study for the Library of Congress

1 Assessment of Options for Handling Full Unicode Character Encodings in MARC21 A Study for the Library of Congress Part 1: New Scripts Jack Cain Senior Consultant Trylus Computing, Toronto 1 Purpose This assessment intends to study the issues and make recommendations on the possible expansion of the character set repertoire for bibliographic records in MARC21 format. 1.1 “Encoding Scheme” vs. “Repertoire” An encoding scheme contains codes by which characters are represented in computer memory. These codes are organized according to a certain methodology called an encoding scheme. The list of all characters so encoded is referred to as the “repertoire” of characters in the given encoding schemes. For example, ASCII is one encoding scheme, perhaps the one best known to the average non-technical person in North America. “A”, “B”, & “C” are three characters in the repertoire of this encoding scheme. These three characters are assigned encodings 41, 42 & 43 in ASCII (expressed here in hexadecimal). 1.2 MARC8 "MARC8" is the term commonly used to refer both to the encoding scheme and its repertoire as used in MARC records up to 1998. The ‘8’ refers to the fact that, unlike Unicode which is a multi-byte per character code set, the MARC8 encoding scheme is principally made up of multiple one byte tables in which each character is encoded using a single 8 bit byte. (It also includes the EACC set which actually uses fixed length 3 bytes per character.) (For details on MARC8 and its specifications see: http://www.loc.gov/marc/.) MARC8 was introduced around 1968 and was initially limited to essentially Latin script only. -

Recognition of Online Handwritten Gurmukhi Strokes Using Support Vector Machine a Thesis

Recognition of Online Handwritten Gurmukhi Strokes using Support Vector Machine A Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Technology Submitted by Rahul Agrawal (Roll No. 601003022) Under the supervision of Dr. R. K. Sharma Professor School of Mathematics and Computer Applications Thapar University Patiala School of Mathematics and Computer Applications Thapar University Patiala – 147004 (Punjab), INDIA June 2012 (i) ABSTRACT Pen-based interfaces are becoming more and more popular and play an important role in human-computer interaction. This popularity of such interfaces has created interest of lot of researchers in online handwriting recognition. Online handwriting recognition contains both temporal stroke information and spatial shape information. Online handwriting recognition systems are expected to exhibit better performance than offline handwriting recognition systems. Our research work presented in this thesis is to recognize strokes written in Gurmukhi script using Support Vector Machine (SVM). The system developed here is a writer independent system. First chapter of this thesis report consist of a brief introduction to handwriting recognition system and some basic differences between offline and online handwriting systems. It also includes various issues that one can face during development during online handwriting recognition systems. A brief introduction about Gurmukhi script has also been given in this chapter In the last section detailed literature survey starting from the 1979 has also been given. Second chapter gives detailed information about stroke capturing, preprocessing of stroke and feature extraction. These phases are considered to be backbone of any online handwriting recognition system. Recognition techniques that have been used in this study are discussed in chapter three. -

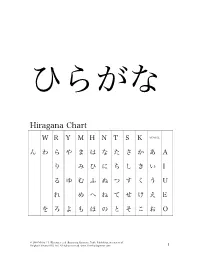

Hiragana Chart

ひらがな Hiragana Chart W R Y M H N T S K VOWEL ん わ ら や ま は な た さ か あ A り み ひ に ち し き い I る ゆ む ふ ぬ つ す く う U れ め へ ね て せ け え E を ろ よ も ほ の と そ こ お O © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 1 Beginning Japanese 名前: ________________________ 1-1 Hiragana Activity Book 日付: ___月 ___日 一、 Practice: あいうえお かきくけこ がぎぐげご O E U I A お え う い あ あ お え う い あ お う あ え い あ お え う い お う い あ お え あ KO KE KU KI KA こ け く き か か こ け く き か こ け く く き か か こ き き か こ こ け か け く く き き こ け か © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 2 GO GE GU GI GA ご げ ぐ ぎ が が ご げ ぐ ぎ が ご ご げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ が が ご げ ぎ が ご ご げ が げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ ご げ が 二、 Fill in each blank with the correct HIRAGANA. SE N SE I KI A RA NA MA E 1. -

Como Digitar Em Japonês 1

Como digitar em japonês 1 Passo 1: Mudar para o modo de digitação em japonês Abra o Office Word, Word Pad ou Bloco de notas para testar a digitação em japonês. Com o cursor colocado em um novo documento em algum lugar em sua tela você vai notar uma barra de idiomas. Clique no botão "PT Português" e selecione "JP Japonês (Japão)". Isso vai mudar a aparência da barra de idiomas. * Se uma barra longa aparecer, como na figura abaixo, clique com o botão direito na parte mais à esquerda e desmarque a opção "Legendas". ficará assim → Além disso, você pode clicar no "_" no canto superior direito da barra de idiomas, que a janela se fechará no canto inferior direito da tela (minimizar). ficará assim → © 2017 Fundação Japão em São Paulo Passo 2: Alterar a barra de idiomas para exibir em japonês Se você não consegue ler em japonês, pode mudar a exibição da barra de idioma para inglês. Clique em ツール e depois na opção プロパティ. Opção: Alterar a barra de idiomas para exibir em inglês Esta janela é toda em japonês, mas não se preocupe, pois da próxima vez que abrí-la estará em Inglês. Haverá um menu de seleção de idiomas no menu de "全般", escolha "英語 " e clique em "OK". © 2017 Fundação Japão em São Paulo Passo 3: Digitando em japonês Certifique-se de que tenha selecionado japonês na barra de idiomas. Após isso, selecione “hiragana”, como indica a seta. Passo 4: Digitando em japonês com letras romanas Uma vez que estiver no modo de entrada correto no documento, vamos digitar uma palavra prática. -

Sinitic Language and Script in East Asia: Past and Present

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 264 December, 2016 Sinitic Language and Script in East Asia: Past and Present edited by Victor H. Mair Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS FOUNDED 1986 Editor-in-Chief VICTOR H. MAIR Associate Editors PAULA ROBERTS MARK SWOFFORD ISSN 2157-9679 (print) 2157-9687 (online) SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series dedicated to making available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor-in-chief actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including romanized modern standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino- Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. Submissions are regularly sent out to be refereed, and extensive editorial suggestions for revision may be offered. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. -

The Twentieth-Century Secularization of the Sinograph in Vietnam, and Its Demotion from the Cosmological to the Aesthetic

Journal of World Literature 1 (2016) 275–293 brill.com/jwl The Twentieth-Century Secularization of the Sinograph in Vietnam, and its Demotion from the Cosmological to the Aesthetic John Duong Phan* Rutgers University [email protected] Abstract This article examines David Damrosch’s notion of “scriptworlds”—spheres of cultural and intellectual transfusion, defined by a shared script—as it pertains to early mod- ern Vietnam’s abandonment of sinographic writing in favor of a latinized alphabet. The Vietnamese case demonstrates a surprisingly rapid readjustment of deeply held attitudes concerning the nature of writing, in the wake of the alphabet’s meteoric suc- cesses. The fluidity of “language ethics” in early modern Vietnam (a society that had long since developed vernacular writing out of an earlier experience of diglossic liter- acy) suggests that the durability of a “scriptworld” depends on the nature and history of literacy in the societies under question. Keywords Vietnamese literature – Vietnamese philology – Chinese philology – script reform – language reform – early modern East Asia/Southeast Asia Introduction In 1919, the French-installed emperor Khải Định permanently dismantled Viet- nam’s civil service examinations, and with them, an entire system of political * I would like to thank Wynn Wilcox, Nguyễn Tuấn Cường, Tuna Artun, and Jack Chia for their valuable help and input. All errors are my own. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2016 | doi: 10.1163/24056480-00102010 Downloaded from Brill.com09/25/2021 07:54:41AM via free access 276 phan selection based on proficiency in Literary Sinitic.1 That same year, using a con- troversial latinized alphabet called Quốc Ngữ (lit. -

Handy Katakana Workbook.Pdf

First Edition HANDY KATAKANA WORKBOOK An Introduction to Japanese Writing: KANA THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT FOR BEGINNING LEVEL JAPANESE LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION. \ FrF!' '---~---- , - Y. M. Shimazu, Ed.D. -----~---- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENlS vii STUDYSHEET#l 1 A,I,U,E, 0, KA,I<I, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #1 2 PRACTICE: A, I,U, E, 0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU, GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #2 3 MORE PRACTICE: A, I, U, E,0, KA,KI,KU, KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #~3 4 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: A,I,U, E,0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N STUDYSHEET #2 5 SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI,ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #4 6 PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, 'lSU,TE,TO, OA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #5 7 MORE PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE,SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE, W, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORKSHEET #6 8 ADDmONAL PRACI'ICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI,TSU,TE,TO, DA, DE,DO STUDYSHEET #3 9 NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE, HO, BA, BI,BU,BE,BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #7 10 PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE,HO, BA,BI, BU,BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #8 11 MORE PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA,HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,BU,BE, BO, PA,PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #9 12 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,3U, BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO STUDYSHEET #4 13 MA, MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET#10 14 PRACTICE: MA,MI, MU,ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #11 15 MORE PRACTICE: MA, MI,MU,ME,MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #12 16 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: MA,MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO STUDYSHEET #5 17 -

Chinese Script Generation Panel Document

Chinese Script Generation Panel Document Proposal for the Generation Panel for the Chinese Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone 1. General Information Chinese script is the logograms used in the writing of Chinese and some other Asian languages. They are called Hanzi in Chinese, Kanji in Japanese and Hanja in Korean. Since the Hanzi unification in the Qin dynasty (221-207 B.C.), the most important change in the Chinese Hanzi occurred in the middle of the 20th century when more than two thousand Simplified characters were introduced as official forms in Mainland China. As a result, the Chinese language has two writing systems: Simplified Chinese (SC) and Traditional Chinese (TC). Both systems are expressed using different subsets under the Unicode definition of the same Han script. The two writing systems use SC and TC respectively while sharing a large common “unchanged” Hanzi subset that occupies around 60% in contemporary use. The common “unchanged” Hanzi subset enables a simplified Chinese user to understand texts written in traditional Chinese with little difficulty and vice versa. The Hanzi in SC and TC have the same meaning and the same pronunciation and are typical variants. The Japanese kanji were adopted for recording the Japanese language from the 5th century AD. Chinese words borrowed into Japanese could be written with Chinese characters, while Japanese words could be written using the character for a Chinese word of similar meaning. Finally, in Japanese, all three scripts (kanji, and the hiragana and katakana syllabaries) are used as main scripts. The Chinese script spread to Korea together with Buddhism from the 2nd century BC to the 5th century AD. -

Source-Based Translation and Foreignization: a Japanese Case

Source-Based Translation and Foreignization Source-Based Translation and Foreignization: A Japanese Case Yukari Fukuchi Meldrum Modern Languages and Cultural Studies, University of Alberta Introduction Foreignization, as currently understood in Translation Studies, is a concept that is charged with “more emphasis on the ideological pressure against the target-language culture than on the faithfulness to the original text” (Tamaki, 2005: 239). In other words, it is a conscious operation of bringing a foreign flavor into translations in order to counteract the effects of domestication, claimed by Venuti (1995) to be the cause of invisibility of translation and translators. Tamaki, in her 2005 paper, also cautions that the concept of foreignization should not be confused with a literal method of translation. Literal translation does not involve ideological intentions and is a mere translation method. In this paper, I will attempt to provide a supporting view that source-based translation, often seen in Japanese translation, needs to be understood outside of foreignization in the above sense. Specifically, I will illustrate that Japanese readers, in premodern times, had to gain specific knowledge and adapt to what was required in order to read and interpret texts in a satisfactory manner. This could have been a factor for the source-orientedness of Japanese translations still observed in a certain form today. By examining this background of Japanese text culture, the more source-based translation is shown to be merely a translation carried out by a literal method without any political or ideological intentions. Therefore, the concept of foreignization does not have a place in Japanese translation. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Simplification of Chinese Characters in Japan and China

CONTRASTING APPROACHES TO CHINESE CHARACTER REFORM: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIMPLIFICATION OF CHINESE CHARACTERS IN JAPAN AND CHINA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIAN STUDIES AUGUST 2012 By Kei Imafuku Thesis Committee: Alexander Vovin, Chairperson Robert Huey Dina Rudolph Yoshimi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express deep gratitude to Alexander Vovin, Robert Huey, and Dina R. Yoshimi for their Japanese and Chinese expertise and kind encouragement throughout the writing of this thesis. Their guidance, as well as the support of the Center for Japanese Studies, School of Pacific and Asian Studies, and the East-West Center, has been invaluable. i ABSTRACT Due to the complexity and number of Chinese characters used in Chinese and Japanese, some characters were the target of simplification reforms. However, Japanese and Chinese simplifications frequently differed, resulting in the existence of multiple forms of the same character being used in different places. This study investigates the differences between the Japanese and Chinese simplifications and the effects of the simplification techniques implemented by each side. The more conservative Japanese simplifications were achieved by instating simpler historical character variants while the more radical Chinese simplifications were achieved primarily through the use of whole cursive script forms and phonetic simplification techniques. These techniques, however, have been criticized for their detrimental effects on character recognition, semantic and phonetic clarity, and consistency – issues less present with the Japanese approach. By comparing the Japanese and Chinese simplification techniques, this study seeks to determine the characteristics of more effective, less controversial Chinese character simplifications.