Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Immigration History

CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE EARLY JAPANESE IMMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES DURING MEIJI TO TAISHO ERA (1868–1926) By HOSOK O Bachelor of Arts in History Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado 2000 Master of Arts in History University of Central Oklahoma Edmond, Oklahoma 2002 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2010 © 2010, Hosok O ii CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE EARLY JAPANESE IMMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES DURING MEIJI TO TAISHO ERA (1868–1926) Dissertation Approved: Dr. Ronald A. Petrin Dissertation Adviser Dr. Michael F. Logan Dr. Yonglin Jiang Dr. R. Michael Bracy Dr. Jean Van Delinder Dr. Mark E. Payton Dean of the Graduate College iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For the completion of my dissertation, I would like to express my earnest appreciation to my advisor and mentor, Dr. Ronald A. Petrin for his dedicated supervision, encouragement, and great friendship. I would have been next to impossible to write this dissertation without Dr. Petrin’s continuous support and intellectual guidance. My sincere appreciation extends to my other committee members Dr. Michael Bracy, Dr. Michael F. Logan, and Dr. Yonglin Jiang, whose intelligent guidance, wholehearted encouragement, and friendship are invaluable. I also would like to make a special reference to Dr. Jean Van Delinder from the Department of Sociology who gave me inspiration for the immigration study. Furthermore, I would like to give my sincere appreciation to Dr. Xiaobing Li for his thorough assistance, encouragement, and friendship since the day I started working on my MA degree to the completion of my doctoral dissertation. -

Japan Between the Wars

JAPAN BETWEEN THE WARS The Meiji era was not followed by as neat and logical a periodi- zation. The Emperor Meiji (his era name was conflated with his person posthumously) symbolized the changes of his period so perfectly that at his death in July 1912 there was a clear sense that an era had come to an end. His successor, who was assigned the era name Taisho¯ (Great Righteousness), was never well, and demonstrated such embarrassing indications of mental illness that his son Hirohito succeeded him as regent in 1922 and re- mained in that office until his father’s death in 1926, when the era name was changed to Sho¯wa. The 1920s are often referred to as the “Taisho¯ period,” but the Taisho¯ emperor was in nominal charge only until 1922; he was unimportant in life and his death was irrelevant. Far better, then, to consider the quarter century between the Russo-Japanese War and the outbreak of the Manchurian Incident of 1931 as the next era of modern Japanese history. There is overlap at both ends, with Meiji and with the resur- gence of the military, but the years in question mark important developments in every aspect of Japanese life. They are also years of irony and paradox. Japan achieved success in joining the Great Powers and reached imperial status just as the territo- rial grabs that distinguished nineteenth-century imperialism came to an end, and its image changed with dramatic swiftness from that of newly founded empire to stubborn advocate of imperial privilege. Its military and naval might approached world standards just as those standards were about to change, and not long before the disaster of World War I produced revul- sion from armament and substituted enthusiasm for arms limi- tations. -

After Kiyozawa: a Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956

After Kiyozawa: A Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956 by Jeff Schroeder Department of Religious Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Richard Jaffe, Supervisor ___________________________ James Dobbins ___________________________ Hwansoo Kim ___________________________ Simon Partner ___________________________ Leela Prasad Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religious Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 ABSTRACT After Kiyozawa: A Study of Shin Buddhist Modernization, 1890-1956 by Jeff Schroeder Department of Religious Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Richard Jaffe, Supervisor ___________________________ James Dobbins ___________________________ Hwansoo Kim ___________________________ Simon Partner ___________________________ Leela Prasad An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religious Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 Copyright by Jeff Schroeder 2015 Abstract This dissertation examines the modern transformation of orthodoxy within the Ōtani denomination of Japanese Shin Buddhism. This history was set in motion by scholar-priest Kiyozawa Manshi (1863-1903), whose calls for free inquiry, introspection, and attainment of awakening in the present life represented major challenges to the -

SUPPORTING the CHINESE, JAPANESE, and KOREAN LANGUAGES in the OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM by Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT the Asian L

SUPPORTING THE CHINESE, JAPANESE, AND KOREAN LANGUAGES IN THE OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM By Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT The Asian language versions of the OpenVMS operating system allow Asian-speaking users to interact with the OpenVMS system in their native languages and provide a platform for developing Asian applications. Since the OpenVMS variants must be able to handle multibyte character sets, the requirements for the internal representation, input, and output differ considerably from those for the standard English version. A review of the Japanese, Chinese, and Korean writing systems and character set standards provides the context for a discussion of the features of the Asian OpenVMS variants. The localization approach adopted in developing these Asian variants was shaped by business and engineering constraints; issues related to this approach are presented. INTRODUCTION The OpenVMS operating system was designed in an era when English was the only language supported in computer systems. The Digital Command Language (DCL) commands and utilities, system help and message texts, run-time libraries and system services, and names of system objects such as file names and user names all assume English text encoded in the 7-bit American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) character set. As Digital's business began to expand into markets where common end users are non-English speaking, the requirement for the OpenVMS system to support languages other than English became inevitable. In contrast to the migration to support single-byte, 8-bit European characters, OpenVMS localization efforts to support the Asian languages, namely Japanese, Chinese, and Korean, must deal with a more complex issue, i.e., the handling of multibyte character sets. -

Sino-Japanese Interactions Through Rare Books

Timelines and Maps Sino-Japanese Interactions Through Rare Books English Version © Keio University Timelines and Maps East Asian History at a Glance Books are part of the flow of history. But it is not only about Japanese history. Many books travel over the sea time to time for several reasons and a lot of knowledge and information comes and go with books. In this course, you’ll see books published in Japan as well as ones come from China and Korea. Let’s take a look at the history in East Asia. You do not have to remember the names of the historical period but please refer to this page for reference. Japanese History Overview This is a list of the main periods in Japanese history. This may be a useful reference as we proceed in the course. Period Name of Era Name of Era - mid-3rd c. CE Yayoi 弥生 mid-3rd c. CE - 7th c. CE Kofun (Tomb period) 古墳 592 - 710 Asuka 飛鳥 710-794 Nara 奈良 794 - 1185 Heian 平安 1185 - 1333 Kamakura 鎌倉 Nanboku-chō 1333 - 1392 (Southern and Northern Courts period) 南北朝 1392 - 1573 Muromachi 室町 1573 - 1603 Azuchi-Momoyama 安土桃山 1603 - 1868 Edo 江戸 1868 - 1912 Meiji 明治 Era names (Nengō) in Edo Period There were several era names (nengo, or gengo) in Edo period (1603 ~ 1868) and they are sometimes used in the description of the old books and materials, especially Week 2 and Week 4. Here is the list of the era names in Edo period for your convenience; 1 SINO-JAPANESE INTERACTIONS THROUGH RARE BOOKS KEIO UNIVERSITY © Keio University Timelines and Maps Start Era name English Start Era name English 1596 慶長 Keichō 1744 延享 Enkyō -

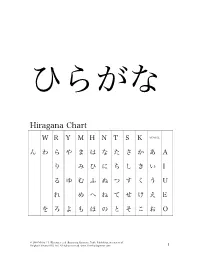

Hiragana Chart

ひらがな Hiragana Chart W R Y M H N T S K VOWEL ん わ ら や ま は な た さ か あ A り み ひ に ち し き い I る ゆ む ふ ぬ つ す く う U れ め へ ね て せ け え E を ろ よ も ほ の と そ こ お O © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 1 Beginning Japanese 名前: ________________________ 1-1 Hiragana Activity Book 日付: ___月 ___日 一、 Practice: あいうえお かきくけこ がぎぐげご O E U I A お え う い あ あ お え う い あ お う あ え い あ お え う い お う い あ お え あ KO KE KU KI KA こ け く き か か こ け く き か こ け く く き か か こ き き か こ こ け か け く く き き こ け か © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 2 GO GE GU GI GA ご げ ぐ ぎ が が ご げ ぐ ぎ が ご ご げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ が が ご げ ぎ が ご ご げ が げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ ご げ が 二、 Fill in each blank with the correct HIRAGANA. SE N SE I KI A RA NA MA E 1. -

Como Digitar Em Japonês 1

Como digitar em japonês 1 Passo 1: Mudar para o modo de digitação em japonês Abra o Office Word, Word Pad ou Bloco de notas para testar a digitação em japonês. Com o cursor colocado em um novo documento em algum lugar em sua tela você vai notar uma barra de idiomas. Clique no botão "PT Português" e selecione "JP Japonês (Japão)". Isso vai mudar a aparência da barra de idiomas. * Se uma barra longa aparecer, como na figura abaixo, clique com o botão direito na parte mais à esquerda e desmarque a opção "Legendas". ficará assim → Além disso, você pode clicar no "_" no canto superior direito da barra de idiomas, que a janela se fechará no canto inferior direito da tela (minimizar). ficará assim → © 2017 Fundação Japão em São Paulo Passo 2: Alterar a barra de idiomas para exibir em japonês Se você não consegue ler em japonês, pode mudar a exibição da barra de idioma para inglês. Clique em ツール e depois na opção プロパティ. Opção: Alterar a barra de idiomas para exibir em inglês Esta janela é toda em japonês, mas não se preocupe, pois da próxima vez que abrí-la estará em Inglês. Haverá um menu de seleção de idiomas no menu de "全般", escolha "英語 " e clique em "OK". © 2017 Fundação Japão em São Paulo Passo 3: Digitando em japonês Certifique-se de que tenha selecionado japonês na barra de idiomas. Após isso, selecione “hiragana”, como indica a seta. Passo 4: Digitando em japonês com letras romanas Uma vez que estiver no modo de entrada correto no documento, vamos digitar uma palavra prática. -

The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented In

Insignificance Given Meaning: The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Masako Inamoto Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Professor Richard Edgar Torrance Professor Naomi Fukumori Professor Shelley Fenno Quinn Copyright by Masako Inamoto 2010 Abstract Kita Morio (1927-), also known as his literary persona Dokutoru Manbô, is one of the most popular and prolific postwar writers in Japan. He is also one of the few Japanese writers who have simultaneously and successfully produced humorous, comical fiction and essays as well as serious literary works. He has worked in a variety of genres. For example, The House of Nire (Nireke no hitobito), his most prominent work, is a long family saga informed by history and Dr. Manbô at Sea (Dokutoru Manbô kôkaiki) is a humorous travelogue. He has also produced in other genres such as children‟s stories and science fiction. This study provides an introduction to Kita Morio‟s fiction and essays, in particular, his versatile writing styles. Also, through the examination of Kita‟s representative works in each genre, the study examines some overarching traits in his writing. For this reason, I have approached his large body of works by according a chapter to each genre. Chapter one provides a biographical overview of Kita Morio‟s life up to the present. The chapter also gives a brief biographical sketch of Kita‟s father, Saitô Mokichi (1882-1953), who is one of the most prominent tanka poets in modern times. -

Handy Katakana Workbook.Pdf

First Edition HANDY KATAKANA WORKBOOK An Introduction to Japanese Writing: KANA THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT FOR BEGINNING LEVEL JAPANESE LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION. \ FrF!' '---~---- , - Y. M. Shimazu, Ed.D. -----~---- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENlS vii STUDYSHEET#l 1 A,I,U,E, 0, KA,I<I, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #1 2 PRACTICE: A, I,U, E, 0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU, GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #2 3 MORE PRACTICE: A, I, U, E,0, KA,KI,KU, KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #~3 4 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: A,I,U, E,0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N STUDYSHEET #2 5 SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI,ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #4 6 PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, 'lSU,TE,TO, OA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #5 7 MORE PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE,SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE, W, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORKSHEET #6 8 ADDmONAL PRACI'ICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI,TSU,TE,TO, DA, DE,DO STUDYSHEET #3 9 NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE, HO, BA, BI,BU,BE,BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #7 10 PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE,HO, BA,BI, BU,BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #8 11 MORE PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA,HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,BU,BE, BO, PA,PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #9 12 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,3U, BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO STUDYSHEET #4 13 MA, MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET#10 14 PRACTICE: MA,MI, MU,ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #11 15 MORE PRACTICE: MA, MI,MU,ME,MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #12 16 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: MA,MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO STUDYSHEET #5 17 -

Android Apps for Learning Kana Recommended by Our Students

Android Apps for learning Kana recommended by our students [Kana column: H = Hiragana, K = Katakana] Below are some recommendations for Kana learning apps, ranked in descending order by our students. Please try a few of these and find one that suits your needs. Enjoy learning Kana! Recommended Points App Name Kana Language Description Link Listening Writing Quizzes English: https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/jpn/id739.html English, Developed by the Japan Foundation and uses Hiragana Memory Hint H Indonesian, 〇 〇 picture mnemonics to help you memorize Indonesian: https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/eng/id746.html Thai Hiragana. Thai: https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/eng/id773.html English: https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/eng/id743.html English, Developed by the Japan Foundation and uses Katakana Memory Hint K Indonesian, 〇 〇 picture mnemonics to help you memorize Indonesian: https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/eng/id747.html Thai Katakana. Thai: https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/eng/id775.html A holistic app that can be used to master Kana Obenkyo H&K English 〇 〇 fully, and eventually also for other skills like https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/eng/id602.html Kanji and grammar. A very integrated quizzing system with five Kana (Hiragana and Katakana) H&K English 〇 〇 https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/jpn/id626.html varieties of tests available. Uses SRS (Spatial Repetition System) to help Kana Town H&K English 〇 〇 https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/eng/id845.html build memory. Although the app is entirely in Japanese, it only has Hiragana and Katakana so the interface Free Learn Japanese Hiragana H&K Japanese 〇 〇 〇 does not pose a problem as such. -

Machine Transliteration (Knight & Graehl, ACL

Machine Transliteration (Knight & Graehl, ACL 97) Kevin Duh UW Machine Translation Reading Group, 11/30/2005 Transliteration & Back-transliteration • Transliteration: • Translating proper names, technical terms, etc. based on phonetic equivalents • Complicated for language pairs with different alphabets & sound inventories • E.g. “computer” --> “konpyuutaa” 䜷䝷䝗䝩䜪䝃䞀 • Back-transliteration • E.g. “konpyuuta” --> “computer” • Inversion of a lossy process Japanese/English Examples • Some notes about Japanese: • Katakana phonetic system for foreign names/loan words • Syllabary writing: • e.g. one symbol for “ga”䚭䜰, one for “gi”䚭䜲 • Consonant-vowel (CV) structure • Less distinction of L/R and H/F sounds • Examples: • Golfbag --> goruhubaggu 䜸䝯䝙䝔䝇䜴 • New York Times --> nyuuyooku taimuzu䚭䝏䝩䞀䝬䞀䜳䚭䝃䜨䝤䜾 • Ice cream --> aisukuriimu 䜦䜨䜽䜳䝮䞀䝤 The Challenge of Machine Back-transliteration • Back-transliteration is an important component for MT systems • For J/E: Katakana phrases are the largest source of phrases that do not appear in bilingual dictionary or training corpora • Claims: • Back-transliteration is less forgiving than transliteration • Back-transliteration is harder than romanization • For J/E, not all katakana phrases can be “sounded out” by back-transliteration • word processing --> waapuro • personal computer --> pasokon Modular WSA and WFSTs • P(w) - generates English words • P(e|w) - English words to English pronounciation • P(j|e) - English to Japanese sound conversion • P(k|j) - Japanese sound to katakana • P(o|k) - katakana to OCR • Given a katana string observed by OCR, find the English word sequence w that maximizes !!!P(w)P(e | w)P( j | e)P(k | j)P(o | k) e j k Two Potential Solutions • Learn from bilingual dictionaries, then generalize • Pro: Simple supervised learning problem • Con: finding direct correspondence between English alphabets and Japanese katakana may be too tenuous • Build a generative model of transliteration, then invert (Knight & Graehl’s approach): 1. -

Legacy Character Sets & Encodings

Legacy & Not-So-Legacy Character Sets & Encodings Ken Lunde CJKV Type Development Adobe Systems Incorporated bc ftp://ftp.oreilly.com/pub/examples/nutshell/cjkv/unicode/iuc15-tb1-slides.pdf Tutorial Overview dc • What is a character set? What is an encoding? • How are character sets and encodings different? • Legacy character sets. • Non-legacy character sets. • Legacy encodings. • How does Unicode fit it? • Code conversion issues. • Disclaimer: The focus of this tutorial is primarily on Asian (CJKV) issues, which tend to be complex from a character set and encoding standpoint. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations dc • GB (China) — Stands for “Guo Biao” (国标 guóbiâo ). — Short for “Guojia Biaozhun” (国家标准 guójiâ biâozhün). — Means “National Standard.” • GB/T (China) — “T” stands for “Tui” (推 tuî ). — Short for “Tuijian” (推荐 tuîjiàn ). — “T” means “Recommended.” • CNS (Taiwan) — 中國國家標準 ( zhôngguó guójiâ biâozhün) in Chinese. — Abbreviation for “Chinese National Standard.” 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations (Cont’d) dc • GCCS (Hong Kong) — Abbreviation for “Government Chinese Character Set.” • JIS (Japan) — 日本工業規格 ( nihon kôgyô kikaku) in Japanese. — Abbreviation for “Japanese Industrial Standard.” — 〄 • KS (Korea) — 한국 공업 규격 (韓國工業規格 hangug gongeob gyugyeog) in Korean. — Abbreviation for “Korean Standard.” — ㉿ — Designation change from “C” to “X” on August 20, 1997. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations (Cont’d) dc • TCVN (Vietnam) — Tiu Chun Vit Nam in Vietnamese. — Means “Vietnamese Standard.” • CJKV — Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated What Is A Character Set? dc • A collection of characters that are intended to be used together to create meaningful text.