Man'yogana.Pdf (574.0Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUPPORTING the CHINESE, JAPANESE, and KOREAN LANGUAGES in the OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM by Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT the Asian L

SUPPORTING THE CHINESE, JAPANESE, AND KOREAN LANGUAGES IN THE OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM By Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT The Asian language versions of the OpenVMS operating system allow Asian-speaking users to interact with the OpenVMS system in their native languages and provide a platform for developing Asian applications. Since the OpenVMS variants must be able to handle multibyte character sets, the requirements for the internal representation, input, and output differ considerably from those for the standard English version. A review of the Japanese, Chinese, and Korean writing systems and character set standards provides the context for a discussion of the features of the Asian OpenVMS variants. The localization approach adopted in developing these Asian variants was shaped by business and engineering constraints; issues related to this approach are presented. INTRODUCTION The OpenVMS operating system was designed in an era when English was the only language supported in computer systems. The Digital Command Language (DCL) commands and utilities, system help and message texts, run-time libraries and system services, and names of system objects such as file names and user names all assume English text encoded in the 7-bit American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) character set. As Digital's business began to expand into markets where common end users are non-English speaking, the requirement for the OpenVMS system to support languages other than English became inevitable. In contrast to the migration to support single-byte, 8-bit European characters, OpenVMS localization efforts to support the Asian languages, namely Japanese, Chinese, and Korean, must deal with a more complex issue, i.e., the handling of multibyte character sets. -

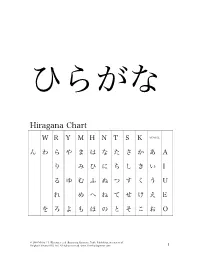

Hiragana Chart

ひらがな Hiragana Chart W R Y M H N T S K VOWEL ん わ ら や ま は な た さ か あ A り み ひ に ち し き い I る ゆ む ふ ぬ つ す く う U れ め へ ね て せ け え E を ろ よ も ほ の と そ こ お O © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 1 Beginning Japanese 名前: ________________________ 1-1 Hiragana Activity Book 日付: ___月 ___日 一、 Practice: あいうえお かきくけこ がぎぐげご O E U I A お え う い あ あ お え う い あ お う あ え い あ お え う い お う い あ お え あ KO KE KU KI KA こ け く き か か こ け く き か こ け く く き か か こ き き か こ こ け か け く く き き こ け か © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 2 GO GE GU GI GA ご げ ぐ ぎ が が ご げ ぐ ぎ が ご ご げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ が が ご げ ぎ が ご ご げ が げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ ご げ が 二、 Fill in each blank with the correct HIRAGANA. SE N SE I KI A RA NA MA E 1. -

Handy Katakana Workbook.Pdf

First Edition HANDY KATAKANA WORKBOOK An Introduction to Japanese Writing: KANA THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT FOR BEGINNING LEVEL JAPANESE LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION. \ FrF!' '---~---- , - Y. M. Shimazu, Ed.D. -----~---- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENlS vii STUDYSHEET#l 1 A,I,U,E, 0, KA,I<I, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #1 2 PRACTICE: A, I,U, E, 0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU, GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #2 3 MORE PRACTICE: A, I, U, E,0, KA,KI,KU, KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #~3 4 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: A,I,U, E,0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N STUDYSHEET #2 5 SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI,ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #4 6 PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, 'lSU,TE,TO, OA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #5 7 MORE PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE,SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE, W, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORKSHEET #6 8 ADDmONAL PRACI'ICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI,TSU,TE,TO, DA, DE,DO STUDYSHEET #3 9 NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE, HO, BA, BI,BU,BE,BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #7 10 PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE,HO, BA,BI, BU,BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #8 11 MORE PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA,HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,BU,BE, BO, PA,PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #9 12 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,3U, BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO STUDYSHEET #4 13 MA, MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET#10 14 PRACTICE: MA,MI, MU,ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #11 15 MORE PRACTICE: MA, MI,MU,ME,MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #12 16 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: MA,MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO STUDYSHEET #5 17 -

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II Class duration: 10 weeks, January 28–April 7, 2020 (no class March 24) Class meetings: Tuesdays at 5:30pm–7:30pm in Hellems 145 Instructor: Megan Husby, [email protected] Class session Resources before coming to Practice exercises after Communicative goals Grammar Vocabulary & topic class class Talking about things that you Verb Conjugation: Past tense Review of Hiragana Intro and あ column Fun Hiragana app for did in the past of long (polite) forms Japanese your Phone (~desu and ~masu verbs) Writing Hiragana か column Talking about your winter System: Hiragana song break Hiragana Hiragana さ column (Recognition) Hiragana Practice クリスマス・ハヌカー・お Hiragana た column Worksheet しょうがつ 正月はなにをしましたか。 Winter Sports どこにいきましたか。 Hiragana な column Grammar Review なにをたべましたか。 New Year’s (Listening) プレゼントをかいましたか/ Vocab Hiragana は column もらいましたか。 Genki I pg. 110 スポーツをしましたか。 Hiragana ま column だれにあいましたか。 Practice Quiz Week 1, えいがをみましたか。 Hiragana や column Jan. 28 ほんをよみましたか。 Omake (bonus): Kasajizō: うたをききましたか/ Hiragana ら column A Folk Tale うたいましたか。 Hiragana わ column Particle と Genki: An Integrated Course in Japanese New Year (Greetings, Elementary Japanese pgs. 24-31 Activities, Foods, Zodiac) (“Japanese Writing System”) Particle と Past Tense of desu (Affirmative) Past Tense of desu (Negative) Past Tense of Verbs Discussing family, pets, objects, Verbs for being (aru and iru) Review of Katakana Intro and ア column Katakana Practice possessions, etc. Japanese Worksheet Counters for people, animals, Writing Katakana カ column etc. System: Genki I pgs. 107-108 Katakana Katakana サ column (Recognition) Practice Quiz Katakana タ column Counters Katakana ナ column Furniture and common Katakana ハ column household items Katakana マ column Katakana ヤ column Katakana ラ column Week 2, Feb. -

Na Kana Magiti Kei Na Lotu

1 NA KANA MAGITI KEI NA LOTU (Vola Tabu : Maciu 22:1-10; Luke 14:12-24) Vola ko Rev. Dr. Ilaitia S. Tuwere. Sa inaki ni vunau oqo me taroga ka sauma talega na taro : A cava na Lotu? Ni da tekivu edaidai ena noda solevu vakalotu, sa na yaga meda taroga ka tovolea talega me sauma na taro oqori. Ia, ena levu na kena isau eda na solia, me vaka na: gumatuataki ni masu kei na vulici ni Vola Tabu, bula vakayalo, muria na ivakarau se lawa ni lotu ka vuqa tale. Na veika oqori era ka dina ka tu kina eso na isau ni taro : A Cava na Lotu. Na i Vola Tabu e sega ni tuvalaka vakavosa vei keda na ibalebale ni lotu. E vakavuqa me boroya vei keda na iyaloyalo me vakadewataka kina na veika eso e vinakata me tukuna. E sega talega ni solia e duabulu ga na iyaloyalo me baleta na lotu. E vuqa sara e solia vei keda. Oqori me vaka na Qele ni Sipi kei na i Vakatawa Vinaka; na Vuni Vaini kei na Tabana; na i Vakavuvuli kei iratou na nona Gonevuli se Tisaipeli, na Masima se Rarama kei Vuravura, na Ulu kei na Vo ni Yago taucoko, ka vuqa tale. Ena mataka edaidai, meda raica vata yani na iyaloyalo ni kana magiti. E rua na kena ivakamacala eda rogoca, mai na Kosipeli i Maciu kei na nei Luke. Na kana magiti se na solevu edua na ivakarau vakaitaukei. Eda soqoni vata kina vakaveiwekani ena noda veikidavaki kei na marau, kena veitalanoa, kena sere kei na meke, kena salusalu kei na kumuni iyau. -

KANA Response Live Organization Administration Tool Guide

This is the most recent version of this document provided by KANA Software, Inc. to Genesys, for the version of the KANA software products licensed for use with the Genesys eServices (Multimedia) products. Click here to access this document. KANA Response Live Organization Administration KANA Response Live Version 10 R2 February 2008 KANA Response Live Organization Administration All contents of this documentation are the property of KANA Software, Inc. (“KANA”) (and if relevant its third party licensors) and protected by United States and international copyright laws. All Rights Reserved. © 2008 KANA Software, Inc. Terms of Use: This software and documentation are provided solely pursuant to the terms of a license agreement between the user and KANA (the “Agreement”) and any use in violation of, or not pursuant to any such Agreement shall be deemed copyright infringement and a violation of KANA's rights in the software and documentation and the user consents to KANA's obtaining of injunctive relief precluding any further such use. KANA assumes no responsibility for any damage that may occur either directly or indirectly, or any consequential damages that may result from the use of this documentation or any KANA software product except as expressly provided in the Agreement, any use hereunder is on an as-is basis, without warranty of any kind, including without limitation the warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, and non-infringement. Use, duplication, or disclosure by licensee of any materials provided by KANA is subject to restrictions as set forth in the Agreement. Information contained in this document is subject to change without notice and does not represent a commitment on the part of KANA. -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role. -

Legacy Character Sets & Encodings

Legacy & Not-So-Legacy Character Sets & Encodings Ken Lunde CJKV Type Development Adobe Systems Incorporated bc ftp://ftp.oreilly.com/pub/examples/nutshell/cjkv/unicode/iuc15-tb1-slides.pdf Tutorial Overview dc • What is a character set? What is an encoding? • How are character sets and encodings different? • Legacy character sets. • Non-legacy character sets. • Legacy encodings. • How does Unicode fit it? • Code conversion issues. • Disclaimer: The focus of this tutorial is primarily on Asian (CJKV) issues, which tend to be complex from a character set and encoding standpoint. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations dc • GB (China) — Stands for “Guo Biao” (国标 guóbiâo ). — Short for “Guojia Biaozhun” (国家标准 guójiâ biâozhün). — Means “National Standard.” • GB/T (China) — “T” stands for “Tui” (推 tuî ). — Short for “Tuijian” (推荐 tuîjiàn ). — “T” means “Recommended.” • CNS (Taiwan) — 中國國家標準 ( zhôngguó guójiâ biâozhün) in Chinese. — Abbreviation for “Chinese National Standard.” 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations (Cont’d) dc • GCCS (Hong Kong) — Abbreviation for “Government Chinese Character Set.” • JIS (Japan) — 日本工業規格 ( nihon kôgyô kikaku) in Japanese. — Abbreviation for “Japanese Industrial Standard.” — 〄 • KS (Korea) — 한국 공업 규격 (韓國工業規格 hangug gongeob gyugyeog) in Korean. — Abbreviation for “Korean Standard.” — ㉿ — Designation change from “C” to “X” on August 20, 1997. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations (Cont’d) dc • TCVN (Vietnam) — Tiu Chun Vit Nam in Vietnamese. — Means “Vietnamese Standard.” • CJKV — Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated What Is A Character Set? dc • A collection of characters that are intended to be used together to create meaningful text. -

History and Narrative in Japanese Chiyuki Kumakura

Document generated on 09/27/2021 10:48 a.m. Surfaces History and Narrative in Japanese Chiyuki Kumakura CULTURE AND INSTITUTIONS Article abstract Volume 5, 1995 This essay analyzes what Oe Kenzaburo (1994 Nobel laureate in literature) calls two opposing poles of ambiguity. The modernization of the Japanese URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1065000ar language has been oriented toward learning from and imitating DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1065000ar Indo-European languages (or Chinese), which permits one to make objective statements. Yet native Japanese (yamato kotoba) is unequivocally oriented by See table of contents the speaker's standpoint which is naturally subjective, reflecting only his/her perceptions and judgments. To Oe, this ambiguous orientation of the Japanese language has forced its culture into obscurity and isolation. In my analysis, the "interpersonal" nature of Japanese (derived from the speaker orientation) and Publisher(s) the interpersonal culture of Japan (derived from the language) have created a Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal culture that appears ambiguous and may often be considered inscrutable from a European perspective. However, interpersonality as a feature of Japanese culture and in Japanese discourse is a new concept that deserves further ISSN examination. 1188-2492 (print) 1200-5320 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Kumakura, C. (1995). History and Narrative in Japanese. Surfaces, 5. https://doi.org/10.7202/1065000ar Copyright © Chiyuki Kumakura, 1995 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. -

D Igital Text

Digital text The joys of character sets Contents Storing text ¡ General problems ¡ Legacy character encodings ¡ Unicode ¡ Markup languages Using text ¡ Processing and display ¡ Programming languages A little bit about writing systems Overview Latin Cyrillic Devanagari − − − − − − Tibetan \ / / Gujarati | \ / − Armenian / Bengali SOGDIAN − Mongolian \ / / Gurumukhi SCRIPT Greek − Georgian / Oriya Chinese | / / | / Telugu / PHOENICIAN BRAHMI − − Kannada SINITIC − Japanese SCRIPT \ SCRIPT Malayalam SCRIPT \ / | \ \ Tamil \ Hebrew | Arabic \ Korean | \ \ − − Sinhala | \ \ | \ \ _ _ Burmese | \ \ Khmer | \ \ Ethiopic Thaana \ _ _ Thai Lao The easy ones Latin is the alphabet and writing system used in the West and some other places Greek and Cyrillic (Russian) are very similar, they just use different characters Armenian and Georgian are also relatively similar More difficult Hebrew is written from right−to−left, but numbers go left−to−right... Arabic has the same rules, but also requires variant selection depending on context and ligature forming The far east Chinese uses two ’alphabets’: hanzi ideographs and zhuyin syllables Japanese mixes four alphabets: kanji ideographs, katakana and hiragana syllables and romaji (latin) letters and numbers Korean uses hangul ideographs, combined from jamo components Vietnamese uses latin letters... The Indic languages Based on syllabic alphabets Require complex ligature forming Letters are not written in logical order, but require a strange ’circular’ ordering In addition, a single line consists of separate -

Characteristics of Developmental Dyslexia in Japanese Kana: From

al Ab gic no lo rm o a h l i c t y i e s s Ogawa et al., J Psychol Abnorm Child 2014, 3:3 P i Journal of Psychological Abnormalities n f o C l DOI: 10.4172/2329-9525.1000126 h a i n l d ISSN:r 2329-9525 r u e o n J in Children Research Article Open Access Characteristics of Developmental Dyslexia in Japanese Kana: from the Viewpoint of the Japanese Feature Shino Ogawa1*, Miwa Fukushima-Murata2, Namiko Kubo-Kawai3, Tomoko Asai4, Hiroko Taniai5 and Nobuo Masataka6 1Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan 2Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology, the University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan 3Faculty of Psychology, Aichi Shukutoku University, Aichi, Japan 4Nagoya City Child Welfare Center, Aichi, Japan 5Department of Pediatrics, Nagoya Central Care Center for Disabled Children, Aichi, Japan 6Section of Cognition and Learning, Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University, Aichi, Japan Abstract This study identified the individual differences in the effects of Japanese Dyslexia. The participants consisted of 12 Japanese children who had difficulties in reading and writing Japanese and were suspected of having developmental disorders. A test battery was created on the basis of the characteristics of the Japanese language to examine Kana’s orthography-to-phonology mapping and target four cognitive skills: analysis of phonological structure, letter-to-sound conversion, visual information processing, and eye–hand coordination. An examination of the individual ability levels for these four elements revealed that reading and writing difficulties are not caused by a single disability, but by a combination of factors. -

AIX Globalization

AIX Version 7.1 AIX globalization IBM Note Before using this information and the product it supports, read the information in “Notices” on page 233 . This edition applies to AIX Version 7.1 and to all subsequent releases and modifications until otherwise indicated in new editions. © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 2010, 2018. US Government Users Restricted Rights – Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents About this document............................................................................................vii Highlighting.................................................................................................................................................vii Case-sensitivity in AIX................................................................................................................................vii ISO 9000.....................................................................................................................................................vii AIX globalization...................................................................................................1 What's new...................................................................................................................................................1 Separation of messages from programs..................................................................................................... 1 Conversion between code sets.............................................................................................................