Characteristics of Developmental Dyslexia in Japanese Kana: From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Translation a Short Introduction to the Japanese Language Will

On Translation A short introduction to the Japanese language will illustrate the kind of difficulties one encounters in translating Japanese into the European languages, and vice versa. Linguistically, Japanese is an isolated language. It has no relation to Chinese. It must have had some relation to Korean, another isolated language, but the two went into different directions thousands of years ago. Some linguists claim that the Japanese language, along with the Korean, belongs to the Ural-Altaic family, yet the claim remains hypothetical. The Japanese language features some characteristics that would seem most strange to those who are only familiar with the European languages. For example, a grammatical subject is unnecessary in Japanese to construct a grammatically complete sentence. “淋しい” (Sabishii) means (someone is) lonely. It is a complete sentence, but there is no subject. The sentence may mean ‘I’m lonely,’ ‘you are lonely,’ ‘he/she is lonely,’ ‘the rock is lonely,’ ‘all human beings are lonely,’ etc, depending on the context. It may furthermore refer to a vague sense of loneliness which needn’t be specified. It is true that in some European languages, such as Italian, a grammatically complete sentence is possible without a named subject. But the subject can always be determined by the inflection of the verb (and often also by the changes in the articles, adjectives and nouns): “Sono sola,” “Sei solo.” A Japanese sentence may be very long and still be without a subject. Tale of Genji , for instance, might contain a sequence of three long sentences without subjects, yet in each a different subject would be implied. -

Man'yogana.Pdf (574.0Kb)

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO Additional services for Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The origin of man'yogana John R. BENTLEY Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies / Volume 64 / Issue 01 / February 2001, pp 59 73 DOI: 10.1017/S0041977X01000040, Published online: 18 April 2001 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0041977X01000040 How to cite this article: John R. BENTLEY (2001). The origin of man'yogana. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 64, pp 5973 doi:10.1017/S0041977X01000040 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO, IP address: 131.156.159.213 on 05 Mar 2013 The origin of man'yo:gana1 . Northern Illinois University 1. Introduction2 The origin of man'yo:gana, the phonetic writing system used by the Japanese who originally had no script, is shrouded in mystery and myth. There is even a tradition that prior to the importation of Chinese script, the Japanese had a native script of their own, known as jindai moji ( , age of the gods script). Christopher Seeley (1991: 3) suggests that by the late thirteenth century, Shoku nihongi, a compilation of various earlier commentaries on Nihon shoki (Japan's first official historical record, 720 ..), circulated the idea that Yamato3 had written script from the age of the gods, a mythical period when the deity Susanoo was believed by the Japanese court to have composed Japan's first poem, and the Sun goddess declared her son would rule the land below. -

Nzila Ye Isa Kwa Bupilo Bo Bu Sa Feli

NzilaYeIsakwa Bupilo Bo Bu Sa Feli Kana Mu I Fumani? ULIMU YA M’ATA OTE ki yena Mubusi wa pupo kamukana. Bupilo bwa luna M bwa cwale ni bwa kwapili bu itingile ku yena. U na ni m’ata a ku fa mupuzonim’ataakufakoto.Unanim’ataakufabupilonim’ataakubu felisa.Haibalutabelwakiyena,likalikalubelahande;haibah’alutabeli,lika ha li na ku lu bela hande. Ki kwa butokwa luli kuli bulapeli bwa luna ibe b’o a amuhela! ˜ Batubalapelakalinzilazenata. Haiba bulapeli bu swana ni nzila, kana Mulimu wa amuhela linzila kaufela za bulapeli? Kutokwa. Jesu, yena mupolofita wa Mulimu, n’a bonisize kuli ku na ni linzila ze peli fela. N’a ize: ˜ “Munyako wa Sinyeho u atami, mi nzila ye ya mwateniiatami,mibabakena ˜ ˜ mwateni ki ba banata. Kakuli munyako wa bupilo wa kumbana, nzila ye ya ˜ mwatenikiyesisani,mikibabanyinyanibabaifumana.”—Mateu7:13,14. ˜ Ku na ni mifuta ye mibeli fela ya bulapeli: bo bunwi bo bu isa kwa ˜ bupilo ni bo bunwibobuisakwasinyeho.Mulelowa broshuwa ye ki ku mi tusa ku fumana nzila ye isa kwa bupilo bo bu sa feli. Mukoloko wa ze Mwahali NzilaYeIsakwa 1 Kana Bulapeli Bupilo Bo Bu Sa Feli KaufelaBuLutaNiti? ......... 4 2 MuKonakuItuta ˜ Kana Mu I Fumani? CwaniNitikazaMulimu? ..... 5 ˜ 3KiBomani Ba Ba Pila mwaLilukolaMoya? ......... 8 4 Bokukululu ba Luna Ba Kai? . 12 5 NitikazaMabiboniBuloi .... 15 6 Kana Mulimu Wa Amuhela BulapeliKaufela?............ 19 ˜ 7KiBomani Ba Ba Na niBulapelibwaNiti? ........ 22 8 Mu Hane Bulapeli bwa Buhata; Mu Swalisane niBulapelibwaNiti ......... 25 9 Bulapeli bwa Niti Bwa Kona kuMiTusaKuYaKuIle!...... 29 2002 Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania Nzila Ye Isa kwa Bupilo Bo Bu Sa Feli—Kana Mu I Fumani? Bahasanyi Printed by Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of South Africa NPC 1 Robert Broom Drive East, Rangeview, Krugersdorp, 1739, R.S.A. -

SUPPORTING the CHINESE, JAPANESE, and KOREAN LANGUAGES in the OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM by Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT the Asian L

SUPPORTING THE CHINESE, JAPANESE, AND KOREAN LANGUAGES IN THE OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM By Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT The Asian language versions of the OpenVMS operating system allow Asian-speaking users to interact with the OpenVMS system in their native languages and provide a platform for developing Asian applications. Since the OpenVMS variants must be able to handle multibyte character sets, the requirements for the internal representation, input, and output differ considerably from those for the standard English version. A review of the Japanese, Chinese, and Korean writing systems and character set standards provides the context for a discussion of the features of the Asian OpenVMS variants. The localization approach adopted in developing these Asian variants was shaped by business and engineering constraints; issues related to this approach are presented. INTRODUCTION The OpenVMS operating system was designed in an era when English was the only language supported in computer systems. The Digital Command Language (DCL) commands and utilities, system help and message texts, run-time libraries and system services, and names of system objects such as file names and user names all assume English text encoded in the 7-bit American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) character set. As Digital's business began to expand into markets where common end users are non-English speaking, the requirement for the OpenVMS system to support languages other than English became inevitable. In contrast to the migration to support single-byte, 8-bit European characters, OpenVMS localization efforts to support the Asian languages, namely Japanese, Chinese, and Korean, must deal with a more complex issue, i.e., the handling of multibyte character sets. -

Problematika České Transkripce Japonštiny a Pravidla Jejího Užívání Nihongo 日本語 社会 Šakai Fudži 富士 Ivona Barešová, Monika Dytrtová Momidži Tókjó もみ じ 東京 Čotto ち ょっ と

チェ コ語 翼 čekogo cubasa šin’jó 信用 Problematika české transkripce japonštiny a pravidla jejího užívání nihongo 日本語 社会 šakai Fudži 富士 Ivona Barešová, Monika Dytrtová momidži Tókjó もみ じ 東京 čotto ち ょっ と PROBLEMATIKA ČESKÉ TRANSKRIPCE JAPONŠTINY A PRAVIDLA JEJÍHO UŽÍVÁNÍ Ivona Barešová Monika Dytrtová Spolupracovala: Bc. Mária Ševčíková Oponenti: prof. Zdeňka Švarcová, Dr. Mgr. Jiří Matela, M.A. Tento výzkum byl umožněn díky účelové podpoře na specifi cký vysokoškolský výzkum udělené roku 2013 Univerzitě Palackého v Olomouci Ministerstvem školství, mládeže a tělovýchovy ČR (FF_2013_044). Neoprávněné užití tohoto díla je porušením autorských práv a může zakládat občanskoprávní, správněprávní, popř. trestněprávní odpovědnost. 1. vydání © Ivona Barešová, Monika Dytrtová, 2014 © Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci, 2014 ISBN 978-80-244-4017-0 Ediční poznámka V publikaci je pro přepis japonských slov užito české transkripce, s výjimkou jejich výskytu v anglic kém textu, kde se objevuje původní transkripce anglická. Japonská jména jsou uváděna v pořadí jméno – příjmení, s výjimkou jejich uvedení v bibliogra- fi ckých citacích, kde se jejich pořadí řídí citační normou. Pokud není uvedeno jinak, autorkami překladů citací a parafrází jsou autorky této práce. V textu jsou použity následující grafi cké prostředky. Fonologický zápis je uveden standardně v šikmých závorkách // a fonetický v hranatých []. Fonetické symboly dle IPA jsou použity v rámci kapi toly 5. V případě, že není nutné zaznamenávat jemné zvukové nuance dané hlásky nebo že není kladen důraz na zvukové rozdíly mezi jed- notlivými hláskami, je jinde v textu, kde je to možné, z důvodu usnadnění porozumění užito namísto těchto specifi ckých fonetických symbolů písmen české abecedy, např. -

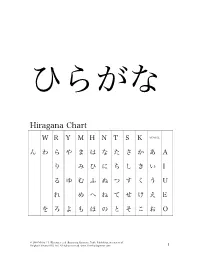

Hiragana Chart

ひらがな Hiragana Chart W R Y M H N T S K VOWEL ん わ ら や ま は な た さ か あ A り み ひ に ち し き い I る ゆ む ふ ぬ つ す く う U れ め へ ね て せ け え E を ろ よ も ほ の と そ こ お O © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 1 Beginning Japanese 名前: ________________________ 1-1 Hiragana Activity Book 日付: ___月 ___日 一、 Practice: あいうえお かきくけこ がぎぐげご O E U I A お え う い あ あ お え う い あ お う あ え い あ お え う い お う い あ お え あ KO KE KU KI KA こ け く き か か こ け く き か こ け く く き か か こ き き か こ こ け か け く く き き こ け か © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 2 GO GE GU GI GA ご げ ぐ ぎ が が ご げ ぐ ぎ が ご ご げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ が が ご げ ぎ が ご ご げ が げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ ご げ が 二、 Fill in each blank with the correct HIRAGANA. SE N SE I KI A RA NA MA E 1. -

Como Digitar Em Japonês 1

Como digitar em japonês 1 Passo 1: Mudar para o modo de digitação em japonês Abra o Office Word, Word Pad ou Bloco de notas para testar a digitação em japonês. Com o cursor colocado em um novo documento em algum lugar em sua tela você vai notar uma barra de idiomas. Clique no botão "PT Português" e selecione "JP Japonês (Japão)". Isso vai mudar a aparência da barra de idiomas. * Se uma barra longa aparecer, como na figura abaixo, clique com o botão direito na parte mais à esquerda e desmarque a opção "Legendas". ficará assim → Além disso, você pode clicar no "_" no canto superior direito da barra de idiomas, que a janela se fechará no canto inferior direito da tela (minimizar). ficará assim → © 2017 Fundação Japão em São Paulo Passo 2: Alterar a barra de idiomas para exibir em japonês Se você não consegue ler em japonês, pode mudar a exibição da barra de idioma para inglês. Clique em ツール e depois na opção プロパティ. Opção: Alterar a barra de idiomas para exibir em inglês Esta janela é toda em japonês, mas não se preocupe, pois da próxima vez que abrí-la estará em Inglês. Haverá um menu de seleção de idiomas no menu de "全般", escolha "英語 " e clique em "OK". © 2017 Fundação Japão em São Paulo Passo 3: Digitando em japonês Certifique-se de que tenha selecionado japonês na barra de idiomas. Após isso, selecione “hiragana”, como indica a seta. Passo 4: Digitando em japonês com letras romanas Uma vez que estiver no modo de entrada correto no documento, vamos digitar uma palavra prática. -

Handy Katakana Workbook.Pdf

First Edition HANDY KATAKANA WORKBOOK An Introduction to Japanese Writing: KANA THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT FOR BEGINNING LEVEL JAPANESE LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION. \ FrF!' '---~---- , - Y. M. Shimazu, Ed.D. -----~---- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENlS vii STUDYSHEET#l 1 A,I,U,E, 0, KA,I<I, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #1 2 PRACTICE: A, I,U, E, 0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU, GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #2 3 MORE PRACTICE: A, I, U, E,0, KA,KI,KU, KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #~3 4 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: A,I,U, E,0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N STUDYSHEET #2 5 SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI,ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #4 6 PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, 'lSU,TE,TO, OA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #5 7 MORE PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE,SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE, W, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORKSHEET #6 8 ADDmONAL PRACI'ICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI,TSU,TE,TO, DA, DE,DO STUDYSHEET #3 9 NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE, HO, BA, BI,BU,BE,BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #7 10 PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE,HO, BA,BI, BU,BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #8 11 MORE PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA,HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,BU,BE, BO, PA,PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #9 12 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,3U, BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO STUDYSHEET #4 13 MA, MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET#10 14 PRACTICE: MA,MI, MU,ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #11 15 MORE PRACTICE: MA, MI,MU,ME,MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #12 16 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: MA,MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO STUDYSHEET #5 17 -

The Japanese Writing Systems, Script Reforms and the Eradication of the Kanji Writing System: Native Speakers’ Views Lovisa Österman

The Japanese writing systems, script reforms and the eradication of the Kanji writing system: native speakers’ views Lovisa Österman Lund University, Centre for Languages and Literature Bachelor’s Thesis Japanese B.A. Course (JAPK11 Spring term 2018) Supervisor: Shinichiro Ishihara Abstract This study aims to deduce what Japanese native speakers think of the Japanese writing systems, and in particular what native speakers’ opinions are concerning Kanji, the logographic writing system which consists of Chinese characters. The Japanese written language has something that most languages do not; namely a total of three writing systems. First, there is the Kana writing system, which consists of the two syllabaries: Hiragana and Katakana. The two syllabaries essentially figure the same way, but are used for different purposes. Secondly, there is the Rōmaji writing system, which is Japanese written using latin letters. And finally, there is the Kanji writing system. Learning this is often at first an exhausting task, because not only must one learn the two phonematic writing systems (Hiragana and Katakana), but to be able to properly read and write in Japanese, one should also learn how to read and write a great amount of logographic signs; namely the Kanji. For example, to be able to read and understand books or newspaper without using any aiding tools such as dictionaries, one would need to have learned the 2136 Jōyō Kanji (regular-use Chinese characters). With the twentieth century’s progress in technology, comparing with twenty years ago, in this day and age one could probably theoretically get by alright without knowing how to write Kanji by hand, seeing as we are writing less and less by hand and more by technological devices. -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role. -

Legacy Character Sets & Encodings

Legacy & Not-So-Legacy Character Sets & Encodings Ken Lunde CJKV Type Development Adobe Systems Incorporated bc ftp://ftp.oreilly.com/pub/examples/nutshell/cjkv/unicode/iuc15-tb1-slides.pdf Tutorial Overview dc • What is a character set? What is an encoding? • How are character sets and encodings different? • Legacy character sets. • Non-legacy character sets. • Legacy encodings. • How does Unicode fit it? • Code conversion issues. • Disclaimer: The focus of this tutorial is primarily on Asian (CJKV) issues, which tend to be complex from a character set and encoding standpoint. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations dc • GB (China) — Stands for “Guo Biao” (国标 guóbiâo ). — Short for “Guojia Biaozhun” (国家标准 guójiâ biâozhün). — Means “National Standard.” • GB/T (China) — “T” stands for “Tui” (推 tuî ). — Short for “Tuijian” (推荐 tuîjiàn ). — “T” means “Recommended.” • CNS (Taiwan) — 中國國家標準 ( zhôngguó guójiâ biâozhün) in Chinese. — Abbreviation for “Chinese National Standard.” 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations (Cont’d) dc • GCCS (Hong Kong) — Abbreviation for “Government Chinese Character Set.” • JIS (Japan) — 日本工業規格 ( nihon kôgyô kikaku) in Japanese. — Abbreviation for “Japanese Industrial Standard.” — 〄 • KS (Korea) — 한국 공업 규격 (韓國工業規格 hangug gongeob gyugyeog) in Korean. — Abbreviation for “Korean Standard.” — ㉿ — Designation change from “C” to “X” on August 20, 1997. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated Terminology & Abbreviations (Cont’d) dc • TCVN (Vietnam) — Tiu Chun Vit Nam in Vietnamese. — Means “Vietnamese Standard.” • CJKV — Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese. 15th International Unicode Conference Copyright © 1999 Adobe Systems Incorporated What Is A Character Set? dc • A collection of characters that are intended to be used together to create meaningful text. -

D Igital Text

Digital text The joys of character sets Contents Storing text ¡ General problems ¡ Legacy character encodings ¡ Unicode ¡ Markup languages Using text ¡ Processing and display ¡ Programming languages A little bit about writing systems Overview Latin Cyrillic Devanagari − − − − − − Tibetan \ / / Gujarati | \ / − Armenian / Bengali SOGDIAN − Mongolian \ / / Gurumukhi SCRIPT Greek − Georgian / Oriya Chinese | / / | / Telugu / PHOENICIAN BRAHMI − − Kannada SINITIC − Japanese SCRIPT \ SCRIPT Malayalam SCRIPT \ / | \ \ Tamil \ Hebrew | Arabic \ Korean | \ \ − − Sinhala | \ \ | \ \ _ _ Burmese | \ \ Khmer | \ \ Ethiopic Thaana \ _ _ Thai Lao The easy ones Latin is the alphabet and writing system used in the West and some other places Greek and Cyrillic (Russian) are very similar, they just use different characters Armenian and Georgian are also relatively similar More difficult Hebrew is written from right−to−left, but numbers go left−to−right... Arabic has the same rules, but also requires variant selection depending on context and ligature forming The far east Chinese uses two ’alphabets’: hanzi ideographs and zhuyin syllables Japanese mixes four alphabets: kanji ideographs, katakana and hiragana syllables and romaji (latin) letters and numbers Korean uses hangul ideographs, combined from jamo components Vietnamese uses latin letters... The Indic languages Based on syllabic alphabets Require complex ligature forming Letters are not written in logical order, but require a strange ’circular’ ordering In addition, a single line consists of separate