LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Contrastive Study of the Ibibio and Igbo Sound Systems

A CONTRASTIVE STUDY OF THE IBIBIO AND IGBO SOUND SYSTEMS GOD’SPOWER ETIM Department Of Languages And Communication Abia State Polytechnic P.M.B. 7166, Aba, Abia State, Nigeria. [email protected] ABSTRACT This research strives to contrast the consonant phonemes, vowel phonemes and tones of Ibibio and Igbo in order to describe their similarities and differences. The researcher adopted the descriptive method, and relevant data on the phonology of the two languages were gathered and analyzed within the framework of CA before making predictions and conclusions. Ibibio consists of ten vowels and fourteen consonant phonemes, while Igbo is made up of eight vowels and twenty-eight consonants. The results of contrastive analysis of the two languages showed that there are similarities as well as differences in the sound systems of the languages. There are some sounds in Ibibio which are not present in Igbo. Also many sounds are in Igbo which do not exist in Ibibio. Both languages share the phonemes /e, a, i, o, ɔ, u, p, b, t, d, k, kp, m, n, ɲ, j, ŋ, f, s, j, w/. All the phonemes in Ibibio are present in Igbo except /ɨ/, /ʉ/, and /ʌ/. Igbo has two vowel segments /ɪ/ and /ʊ/ and also fourteen consonant phonemes /g, gb, kw, gw, ŋw, v, z, ʃ, h, ɣ, ʧ, ʤ, l, r/ which Ibibio lacks. Both languages have high, low and downstepped tones but Ibibio further has contour or gliding tones which are not tone types in Igbo. Also, the downstepped tone in Ibibio is conventionally marked with exclamation point, while in Igbo, it is conventionally marked with a raised macron over the segments bearing it. -

Vowel Quality and Phonological Projection

i Vowel Quality and Phonological Pro jection Marc van Oostendorp PhD Thesis Tilburg University September Acknowledgements The following p eople have help ed me prepare and write this dissertation John Alderete Elena Anagnostop oulou Sjef Barbiers Outi BatEl Dorothee Beermann Clemens Bennink Adams Bo domo Geert Bo oij Hans Bro ekhuis Norb ert Corver Martine Dhondt Ruud and Henny Dhondt Jo e Emonds Dicky Gilb ers Janet Grijzenhout Carlos Gussenhoven Gert jan Hakkenb erg Marco Haverkort Lars Hellan Ben Hermans Bart Holle brandse Hannekevan Ho of Angeliek van Hout Ro eland van Hout Harry van der Hulst Riny Huybregts Rene Kager HansPeter Kolb Emiel Krah mer David Leblanc Winnie Lechner Klarien van der Linde John Mc Carthy Dominique Nouveau Rolf Noyer Jaap and Hannyvan Oosten dorp Paola Monachesi Krisztina Polgardi Alan Prince Curt Rice Henk van Riemsdijk Iggy Ro ca Sam Rosenthall Grazyna Rowicka Lisa Selkirk Chris Sijtsma Craig Thiersch MiekeTrommelen Rub en van der Vijver Janneke Visser Riet Vos Jero en van de Weijer Wim Zonneveld Iwant to thank them all They have made the past four years for what it was the most interesting and happiest p erio d in mylife until now ii Contents Intro duction The Headedness of Syllables The Headedness Hyp othesis HH Theoretical Background Syllable Structure Feature geometry Sp ecication and Undersp ecicati on Skeletal tier Mo del of the grammar Optimality Theory Data Organisation of the thesis Chapter Chapter -

A Brief Description of Consonants in Modern Standard Arabic

Linguistics and Literature Studies 2(7): 185-189, 2014 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/lls.2014.020702 A Brief Description of Consonants in Modern Standard Arabic Iram Sabir*, Nora Alsaeed Al-Jouf University, Sakaka, KSA *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Copyright © 2014 Horizon Research Publishing All rights reserved. Abstract The present study deals with “A brief Modern Standard Arabic. This study starts from an description of consonants in Modern Standard Arabic”. This elucidation of the phonetic bases of sounds classification. At study tries to give some information about the production of this point shows the first limit of the study that is basically Arabic sounds, the classification and description of phonetic rather than phonological description of sounds. consonants in Standard Arabic, then the definition of the This attempt of classification is followed by lists of the word consonant. In the present study we also investigate the consonant sounds in Standard Arabic with a key word for place of articulation in Arabic consonants we describe each consonant. The criteria of description are place and sounds according to: bilabial, labio-dental, alveolar, palatal, manner of articulation and voicing. The attempt of velar, uvular, and glottal. Then the manner of articulation, description has been made to lead to the drawing of some the characteristics such as phonation, nasal, curved, and trill. fundamental conclusion at the end of the paper. The aim of this study is to investigate consonant in MSA taking into consideration that all 28 consonants of Arabic alphabets. As a language Arabic is one of the most 2. -

Sociophonetic Variation in Bolivian Quechua Uvular Stops

Title Page Sociophonetic Variation in Bolivian Quechua Uvular Stops by Eva Bacas University of Pittsburgh, 2019 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2019 Committee Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This thesis was presented by Eva Bacas It was defended on November 8, 2019 and approved by Alana DeLoge, Quechua Instructor, Department of Linguistics, University of Pittsburgh Melinda Fricke, Assistant Professor, Department of Linguistics, University of Pittsburgh Gillian Gallagher, Associate Professor, Department of Linguistics, New York University Thesis Advisor/Dissertation Director: Claude Mauk, Senior Lecturer, Department of Linguistics, University of Pittsburgh ii Copyright © by Eva Bacas 2019 iii Abstract Sociophonetic Variation in Bolivian Quechua Uvular Stops Eva Bacas, BPhil University of Pittsburgh, 2019 Quechua is an indigenous language of the Andes region of South America. In Cochabamba, Bolivia, Quechua and Spanish have been in contact for over 500 years. In this thesis, I explore sociolinguistic variation among bilingual speakers of Cochabamba Quechua (CQ) and Spanish by investigating the relationship between the production of the voiceless uvular stop /q/ and speakers’ sociolinguistic backgrounds. I conducted a speech production study and sociolinguistic interview with seven bilingual CQ-Spanish speakers. I analyzed manner of articulation and place of articulation variation. Results indicate that manner of articulation varies primarily due to phonological factors, and place of articulation varies according to sociolinguistic factors. This reveals that among bilingual CQ-Spanish speakers, production of voiceless uvular stop /q/ does vary sociolinguistically. -

2 Mora and Syllable

2 Mora and Syllable HARUO KUBOZONO 0 Introduction In his classical typological study Trubetzkoy (1969) proposed that natural languages fall into two groups, “mora languages” and “syllable languages,” according to the smallest prosodic unit that is used productively in that lan- guage. Tokyo Japanese is classified as a “mora” language whereas Modern English is supposed to be a “syllable” language. The mora is generally defined as a unit of duration in Japanese (Bloch 1950), where it is used to measure the length of words and utterances. The three words in (1), for example, are felt by native speakers of Tokyo Japanese as having the same length despite the different number of syllables involved. In (1) and the rest of this chapter, mora boundaries are marked by hyphens /-/, whereas syllable boundaries are marked by dots /./. All syllable boundaries are mora boundaries, too, although not vice versa.1 (1) a. to-o-kyo-o “Tokyo” b. a-ma-zo-n “Amazon” too.kyoo a.ma.zon c. a-me-ri-ka “America” a.me.ri.ka The notion of “mora” as defined in (1) is equivalent to what Pike (1947) called a “phonemic syllable,” whereas “syllable” in (1) corresponds to what he referred to as a “phonetic syllable.” Pike’s choice of terminology as well as Trubetzkoy’s classification may be taken as implying that only the mora is relevant in Japanese phonology and morphology. Indeed, the majority of the literature emphasizes the importance of the mora while essentially downplaying the syllable (e.g. Sugito 1989, Poser 1990, Tsujimura 1996b). This symbolizes the importance of the mora in Japanese, but it remains an open question whether the syllable is in fact irrelevant in Japanese and, if not, what role this second unit actually plays in the language. -

A Student Model of Katakana Reading Proficiency for a Japanese Language Intelligent Tutoring System

A Student Model of Katakana Reading Proficiency for a Japanese Language Intelligent Tutoring System Anthony A. Maciejewski Yun-Sun Kang School of Electrical Engineering Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana 47907 Abstract--Thls work describes the development of a kanji. Due to the limited number of kana, their relatively low student model that Is used In a Japanese language visual complexity, and their systematic arrangement they do Intelligent tutoring system to assess a pupil's not represent a significant barrier to the student of Japanese. proficiency at reading one of the distinct In fact, the relatively small effort required to learn katakana orthographies of Japanese, known as k a t a k a n a , yields significant returns to readers of technical Japanese due to While the effort required to memorize the relatively the high incidence of terms derived from English and few k a t a k a n a symbols and their associated transliterated into katakana. pronunciations Is not prohibitive, a major difficulty In reading katakana Is associated with the phonetic This work describes the development of a system that is modifications which occur when English words used to automatically acquire knowledge about how English which are transliterated Into katakana are made to words are transliterated into katakana and then to use that conform to the more restrictive rules of Japanese information in developing a model of a student's proficiency in phonology. The algorithm described here Is able to reading katakana. This model is used to guide the instruction automatically acquire a knowledge base of these of the student using an intelligent tutoring system developed phonological transformation rules, use them to previously [6,8]. -

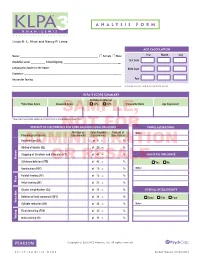

Sample, Not for Administration Or Resale

ANALYSIS FORM Linda M. L. Khan and Nancy P. Lewis Age Calculation Name: ______________________________________________________ u Female u Male Year Month Day Test Date Grade/Ed. Level: __________ School/Agency: __________________________________________ Language(s) Spoken in the Home: ___________________________________________________ Birth Date Examiner: ____________________________________________________________________ Reason for Testing: ______________________________________________________________ Age ____________________________________________________________________________ Reminder: Do not round up to next month or year. KLPA–3 Score Summary Confidence Interval *Total Raw Score Standard Score 90% 95% Percentile Rank Age Equivalent SAMPLE,– * Raw score equals total number of occurrences of scored phonological processes. Percent of OccurrenceNOT for Core Phonological ProcessesFOR Vowel Alterations Number of Total Possible Percent of Notes: Phonological Process Occurrences Occurrences Occurrences DeaffricationADMINISTRATION (DF) of 8 = % Gliding of liquids (GL) of 20 = % Stopping of fricatives and affricates (ST) of 48 = % Dialectal Influence Manner OR RESALE Stridency deletion (STR) of 42 = % Yes No Vocalization (VOC) of 15 = % Notes: Palatal fronting (PF) of 12 = % Place Velar fronting (VF) of 23 = % Cluster simplification (CS) of 23 = % Overall Intelligibility Deletion of final consonant (DFC) of 36 = % Good Fair Poor Reduction Syllable reduction (SR) of 25 = % Notes: Final devoicing (FDV) of 35 = % Voicing Initial voicing -

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics Title The Aeroacoustics of Nasalized Fricatives Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/00h9g9gg Author Shosted, Ryan K Publication Date 2006 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Aeroacoustics of Nasalized Fricatives by Ryan Keith Shosted B.A. (Brigham Young University) 2000 M.A. (University of California, Berkeley) 2003 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: John J. Ohala, Chair Keith Johnson Milton M. Azevedo Fall 2006 The dissertation of Ryan Keith Shosted is approved: Chair Date Date Date University of California, Berkeley Fall 2006 The Aeroacoustics of Nasalized Fricatives Copyright 2006 by Ryan Keith Shosted 1 Abstract The Aeroacoustics of Nasalized Fricatives by Ryan Keith Shosted Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley John J. Ohala, Chair Understanding the relationship of aerodynamic laws to the unique geometry of the hu- man vocal tract allows us to make phonological and typological predictions about speech sounds typified by particular aerodynamic regimes. For example, some have argued that the realization of nasalized fricatives is improbable because fricatives and nasals have an- tagonistic aerodynamic specifications. Fricatives require high pressure behind the suprala- ryngeal constriction as a precondition for high particle velocity. Nasalization, on the other hand, vents back pressure by allowing air to escape through the velopharyngeal orifice. This implies that an open velopharyngeal port will reduce oral particle velocity, thereby potentially extinguishing frication. By using a mechanical model of the vocal tract and spoken fricatives that have undergone coarticulatory nasalization, it is shown that nasal- ization must alter the spectral characteristics of fricatives, e.g. -

Part 1: Introduction to The

PREVIEW OF THE IPA HANDBOOK Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet PARTI Introduction to the IPA 1. What is the International Phonetic Alphabet? The aim of the International Phonetic Association is to promote the scientific study of phonetics and the various practical applications of that science. For both these it is necessary to have a consistent way of representing the sounds of language in written form. From its foundation in 1886 the Association has been concerned to develop a system of notation which would be convenient to use, but comprehensive enough to cope with the wide variety of sounds found in the languages of the world; and to encourage the use of thjs notation as widely as possible among those concerned with language. The system is generally known as the International Phonetic Alphabet. Both the Association and its Alphabet are widely referred to by the abbreviation IPA, but here 'IPA' will be used only for the Alphabet. The IPA is based on the Roman alphabet, which has the advantage of being widely familiar, but also includes letters and additional symbols from a variety of other sources. These additions are necessary because the variety of sounds in languages is much greater than the number of letters in the Roman alphabet. The use of sequences of phonetic symbols to represent speech is known as transcription. The IPA can be used for many different purposes. For instance, it can be used as a way to show pronunciation in a dictionary, to record a language in linguistic fieldwork, to form the basis of a writing system for a language, or to annotate acoustic and other displays in the analysis of speech. -

Vocale Incerta, Vocale Aperta*

Vocale Incerta, Vocale Aperta* Michael Kenstowicz Massachusetts Institute of Technology Omaggio a P-M. Bertinetto Ogni toscano si comporta di fronte a una parola a lui nuova, come si nota p. es. nella lettura del latino, scegliendo costantamente, e inconsciamente, il timbro aperto, secondo il principio che il Migliorini ha condensato nella formula «vocale incerta, vocale aperta»…è il processo a cui vien sottoposto ogni vocabolo importato o adattato da altri linguaggi. (Franceschi 1965:1-3) 1. Introduction Standard Italian distinguishes seven vowels in stressed nonfinal syllables. The open ɛ,ɔ vs. closed e,o mid-vowel contrast (transcribed here as open è,ò vs. closed é,ó) is neutralized in unstressed position (1). (1) 3 sg. infinitive tócca toccàre ‘touch’ blòcca bloccàre ‘block’ péla pelàre ‘pluck’ * A preliminary version of this paper was presented at the MIT Phonology Circle and the 40th Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages, University of Washington (March 2010). Thanks to two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments as well as to Maria Giavazzi, Giovanna Marotta, Joan Mascaró, Andrea Moro, and Mario Saltarelli. 1 gèla gelàre ‘freeze’ The literature uniformly identifies the unstressed vowels as closed. Consequently, the open è and ò have more restricted distribution and hence by traditional criteria would be identified as "marked" (Krämer 2009). In this paper we examine various lines of evidence indicating that the open vowels are optimal in stressed (open) syllables (the rafforzamento of Nespor 1993) and thus that the closed é and ó are "marked" in this position: {è,ò} > {é,ó} (where > means “better than” in the Optimality Theoretic sense). -

UC Berkeley Phonlab Annual Report

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley PhonLab Annual Report Title Strengthening, Weakening and Variability: The Articulatory Correlates of Hypo- and Hyper- articulation in the Production of English Dental Fricatives Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1hw2719n Journal UC Berkeley PhonLab Annual Report, 14(1) ISSN 2768-5047 Author Melguy, Yevgeniy Publication Date 2018 DOI 10.5070/P7141042482 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UC Berkeley Phonetics and Phonology Lab Annual Report (2018) Yevgeniy Melguy Susan Lin, Brian Smith M.A. Qualifying Paper 9 December 2018 Strengthening, weakening and variability: The articulatory correlates of hypo- and hyper- articulation in the production of English dental fricatives 1. INTRODUCTION A number of influential approaches to understanding phonetic and phonological variation in speech have highlighted the importance of functional factors (Blevins, 2004; Donegan & Stampe, 1979; Kiparsky, 1988; Kirchner, 1998; Lindblom, 1990). Under such approaches, speaker- and listener-oriented principles—ease of articulation vs. perceptual clarity—often work in opposite directions with respect to consonantal articulation. Minimization of effort is thought to drive a general “weakening” of consonants (resulting in decreased articulatory constriction and/or duration) which often makes them more articulatorily similar to surrounding sounds. This can result in assimilation, lenition, and ultimately deletion, and generally comes at the expense of clarity. By contrast, maximization of clarity drives consonantal “strengthening” processes (resulting in increased articulatory constriction and/or duration) that makes target segments more distinct from neighboring sounds, which can result in fortition. Clear speech generally involves more extreme or “forceful” articulations, and usually comes at the expense of requiring more articulatory effort from the speaker. -

The Sound Patterns of Camuno: Description and Explanation in Evolutionary Phonology

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2014 The Sound Patterns Of Camuno: Description And Explanation In Evolutionary Phonology Michela Cresci Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/191 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE SOUND PATTERNS OF CAMUNO: DESCRIPTION AND EXPLANATION IN EVOLUTIONARY PHONOLOGY by MICHELA CRESCI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City Universtiy of New York 2014 i 2014 MICHELA CRESCI All rights reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Linguistics in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. JULIETTE BLEVINS ____________________ __________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee GITA MARTOHARDJONO ____________________ ___________________________________ Date Executive Officer KATHLEEN CURRIE HALL DOUGLAS H. WHALEN GIOVANNI BONFADINI Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract THE SOUND PATTERNS OF CAMUNO: DESCRIPTION AND EXPLANATION IN EVOLUTIONARY PHONOLOGY By Michela Cresci Advisor: Professor Juliette Blevins This dissertation presents a linguistic study of the sound patterns of Camuno framed within Evolutionary Phonology (Blevins, 2004, 2006, to appear). Camuno is a variety of Eastern Lombard, a Romance language of northern Italy, spoken in Valcamonica. Camuno is not a local variety of Italian, but a sister of Italian, a local divergent development of the Latin originally spoken in Italy (Maiden & Perry, 1997, p.