Phonological Differences Between Japanese and English: Several Potentially Problematic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 Mora and Syllable

2 Mora and Syllable HARUO KUBOZONO 0 Introduction In his classical typological study Trubetzkoy (1969) proposed that natural languages fall into two groups, “mora languages” and “syllable languages,” according to the smallest prosodic unit that is used productively in that lan- guage. Tokyo Japanese is classified as a “mora” language whereas Modern English is supposed to be a “syllable” language. The mora is generally defined as a unit of duration in Japanese (Bloch 1950), where it is used to measure the length of words and utterances. The three words in (1), for example, are felt by native speakers of Tokyo Japanese as having the same length despite the different number of syllables involved. In (1) and the rest of this chapter, mora boundaries are marked by hyphens /-/, whereas syllable boundaries are marked by dots /./. All syllable boundaries are mora boundaries, too, although not vice versa.1 (1) a. to-o-kyo-o “Tokyo” b. a-ma-zo-n “Amazon” too.kyoo a.ma.zon c. a-me-ri-ka “America” a.me.ri.ka The notion of “mora” as defined in (1) is equivalent to what Pike (1947) called a “phonemic syllable,” whereas “syllable” in (1) corresponds to what he referred to as a “phonetic syllable.” Pike’s choice of terminology as well as Trubetzkoy’s classification may be taken as implying that only the mora is relevant in Japanese phonology and morphology. Indeed, the majority of the literature emphasizes the importance of the mora while essentially downplaying the syllable (e.g. Sugito 1989, Poser 1990, Tsujimura 1996b). This symbolizes the importance of the mora in Japanese, but it remains an open question whether the syllable is in fact irrelevant in Japanese and, if not, what role this second unit actually plays in the language. -

A Student Model of Katakana Reading Proficiency for a Japanese Language Intelligent Tutoring System

A Student Model of Katakana Reading Proficiency for a Japanese Language Intelligent Tutoring System Anthony A. Maciejewski Yun-Sun Kang School of Electrical Engineering Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana 47907 Abstract--Thls work describes the development of a kanji. Due to the limited number of kana, their relatively low student model that Is used In a Japanese language visual complexity, and their systematic arrangement they do Intelligent tutoring system to assess a pupil's not represent a significant barrier to the student of Japanese. proficiency at reading one of the distinct In fact, the relatively small effort required to learn katakana orthographies of Japanese, known as k a t a k a n a , yields significant returns to readers of technical Japanese due to While the effort required to memorize the relatively the high incidence of terms derived from English and few k a t a k a n a symbols and their associated transliterated into katakana. pronunciations Is not prohibitive, a major difficulty In reading katakana Is associated with the phonetic This work describes the development of a system that is modifications which occur when English words used to automatically acquire knowledge about how English which are transliterated Into katakana are made to words are transliterated into katakana and then to use that conform to the more restrictive rules of Japanese information in developing a model of a student's proficiency in phonology. The algorithm described here Is able to reading katakana. This model is used to guide the instruction automatically acquire a knowledge base of these of the student using an intelligent tutoring system developed phonological transformation rules, use them to previously [6,8]. -

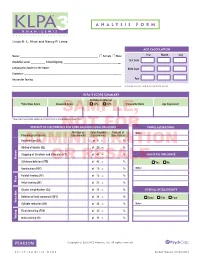

Sample, Not for Administration Or Resale

ANALYSIS FORM Linda M. L. Khan and Nancy P. Lewis Age Calculation Name: ______________________________________________________ u Female u Male Year Month Day Test Date Grade/Ed. Level: __________ School/Agency: __________________________________________ Language(s) Spoken in the Home: ___________________________________________________ Birth Date Examiner: ____________________________________________________________________ Reason for Testing: ______________________________________________________________ Age ____________________________________________________________________________ Reminder: Do not round up to next month or year. KLPA–3 Score Summary Confidence Interval *Total Raw Score Standard Score 90% 95% Percentile Rank Age Equivalent SAMPLE,– * Raw score equals total number of occurrences of scored phonological processes. Percent of OccurrenceNOT for Core Phonological ProcessesFOR Vowel Alterations Number of Total Possible Percent of Notes: Phonological Process Occurrences Occurrences Occurrences DeaffricationADMINISTRATION (DF) of 8 = % Gliding of liquids (GL) of 20 = % Stopping of fricatives and affricates (ST) of 48 = % Dialectal Influence Manner OR RESALE Stridency deletion (STR) of 42 = % Yes No Vocalization (VOC) of 15 = % Notes: Palatal fronting (PF) of 12 = % Place Velar fronting (VF) of 23 = % Cluster simplification (CS) of 23 = % Overall Intelligibility Deletion of final consonant (DFC) of 36 = % Good Fair Poor Reduction Syllable reduction (SR) of 25 = % Notes: Final devoicing (FDV) of 35 = % Voicing Initial voicing -

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin Essay Title: The sound system of Japanese This essay aims to introduce the sound system of Japanese, including the inventories of consonants, vowels, and diphthongs. The phonological variations of the sound segments in different phonetic environments are also included. For the illustration, word examples are given and they are presented in the following format: [IPA] (Romaji: “meaning”). Consonants In Japanese, there are 14 core consonants, and some of them have a lot of allophonic variations. The various types of consonants classified with respect to their manner of articulation are presented as follows. Stop Japanese has six oral stops or plosives, /p b t d k g/, which are classified into three place categories, bilabial, alveolar, and velar, as listed below. In each place category, there is a pair of plosives with the contrast in voicing. /p/ = a voiceless bilabial plosive [p]: [ippai] (ippai: “A cup of”) /b/ = a voiced bilabial plosive [b]: [baɴ] (ban: “Night”) /t/ = a voiceless alveolar plosive [t]: [oto̞ ːto̞ ] (ototo: “Brother”) /d/ = a voiced alveolar plosive [d]: [to̞ mo̞ datɕi] (tomodachi: “Friend”) /k/ = a voiceless velar plosive [k]: [kaiɰa] (kaiwa: “Conversation”) /g/ = a voiced velar plosive [g]: [ɡakɯβsai] (gakusai: “Student”) Phonetically, Japanese also has a glottal stop [ʔ] which is commonly produced to separate the neighboring vowels occurring in different syllables. This phonological phenomenon is known as ‘glottal stop insertion’. The glottal stop may be realized as a pause, which is used to indicate the beginning or the end of an utterance. For instance, the word “Japanese money” is actually pronounced as [ʔe̞ ɴ], instead of [je̞ ɴ], and the pronunciation of “¥15” is [dʑɯβːɡo̞ ʔe̞ ɴ]. -

A Case Study of Norwegian Clusters

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title Morphological derived-environment effects in gestural coordination: A case study of Norwegian clusters Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5mn3w7gz Journal Lingua, 117 ISSN 0024-3841 Author Bradley, Travis G. Publication Date 2007-06-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Bradley, Travis G. 2007. Morphological Derived-Environment Effects in Gestural Coordination: A Case Study of Norwegian Clusters. Lingua 117.6:950-985. Morphological derived-environment effects in gestural coordination: a case study of Norwegian clusters Travis G. Bradley* Department of Spanish and Classics, University of California, 705 Sproul Hall, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616, USA Abstract This paper examines morphophonological alternations involving apicoalveolar tap- consonant clusters in Urban East Norwegian from the framework of gestural Optimality Theory. Articulatory Phonology provides an insightful explanation of patterns of vowel intrusion, coalescence, and rhotic deletion in terms of the temporal coordination of consonantal gestures, which interacts with both prosodic and morphological structure. An alignment-based account of derived-environment effects is proposed in which complete overlap in rhotic-consonant clusters is blocked within morphemes but not across morpheme or word boundaries. Alignment constraints on gestural coordination also play a role in phonologically conditioned allomorphy. The gestural analysis is contrasted with alternative Optimality-theoretic accounts. Furthermore, it is argued that models of the phonetics-phonology interface which view timing as a low-level detail of phonetic implementation incorrectly predict that input morphological structure should have no effect on gestural coordination. The patterning of rhotic-consonant clusters in Norwegian is consistent with a model that includes gestural representations and constraints directly in the phonological grammar, where underlying morphological structure is still visible. -

Masterarbeit / Master's Thesis

MASTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS Titel der Masterarbeit / Title of the Master’s Thesis “Dating the split of the Japonic language family. The Pre-Old Japanese corpus” verfasst von / submitted by Patrick Elmer, BA MA angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) Wien, 2019 / Vienna 2019 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / A 066 599 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Masterstudium Indogermanistik und historische degree programme as it appears on Sprachwissenschaft UG2002 the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Melanie Malzahn, Privatdoz. Table of contents Part 1: Introduction ..................................................................................................... 8 1.1 The Japonic language family .............................................................................................. 9 1.2 Previous research: When did Japonic split into Japanese and Ryūkyūan .......................... 11 1.3 Research question and scope of study .............................................................................. 15 1.4 Methodology ................................................................................................................... 16 Part 2: Language data ................................................................................................ 19 2.1 Old Japanese ................................................................................................................... -

Introduction to Japanese Computational Linguistics Francis Bond and Timothy Baldwin

1 Introduction to Japanese Computational Linguistics Francis Bond and Timothy Baldwin The purpose of this chapter is to provide a brief introduction to the Japanese language, and natural language processing (NLP) research on Japanese. For a more complete but accessible description of the Japanese language, we refer the reader to Shibatani (1990), Backhouse (1993), Tsujimura (2006), Yamaguchi (2007), and Iwasaki (2013). 1 A Basic Introduction to the Japanese Language Japanese is the official language of Japan, and belongs to the Japanese language family (Gordon, Jr., 2005).1 The first-language speaker pop- ulation of Japanese is around 120 million, based almost exclusively in Japan. The official version of Japanese, e.g. used in official settings andby the media, is called hyōjuNgo “standard language”, but Japanese also has a large number of distinctive regional dialects. Other than lexical distinctions, common features distinguishing Japanese dialects are case markers, discourse connectives and verb endings (Kokuritsu Kokugo Kenkyujyo, 1989–2006). 1There are a number of other languages in the Japanese language family of Ryukyuan type, spoken in the islands of Okinawa. Other languages native to Japan are Ainu (an isolated language spoken in northern Japan, and now almost extinct: Shibatani (1990)) and Japanese Sign Language. Readings in Japanese Natural Language Processing. Francis Bond, Timothy Baldwin, Kentaro Inui, Shun Ishizaki, Hiroshi Nakagawa and Akira Shimazu (eds.). Copyright © 2016, CSLI Publications. 1 Preview 2 / Francis Bond and Timothy Baldwin 2 The Sound System Japanese has a relatively simple sound system, made up of 5 vowel phonemes (/a/,2 /i/, /u/, /e/ and /o/), 9 unvoiced consonant phonemes (/k/, /s/,3 /t/,4 /n/, /h/,5 /m/, /j/, /ó/ and /w/), 4 voiced conso- nants (/g/, /z/,6 /d/ 7 and /b/), and one semi-voiced consonant (/p/). -

Phonotactically-Driven Rendaku in Surnames: a Linguistic Study Using Social Media

Phonotactically-DrivenRendakuinSurnames: ALinguisticStudyUsingSocialMedia YuTanaka 1. Introduction Like regular compound words, Japanese surnames with a compound structure can undergo a voicing alternation known as rendaku. Rendaku application in surnames is somewhat different from that in regular compounds, however; the voicing alternation is governed by avoidance of consonant sequences that are similar in terms of voicing and place. Although the peculiarity of rendaku in surnames has been noted in the literature (see Sugito, 1965 among others), no study has provided a full description or explanation of the patterns. The first aim of this study is thus to better describe the data. A corpus of rendaku in surnames is created using social media, which enables us to assess comprehensively and quantitatively the validity of proposed generalizations. The second aim of the study is to explain why rendaku applies in a different manner in names and in normal words. I propose that compound names are treated as if they are single stems and that the peculiar rendaku patterns in surnames can be attributed to stem-internal phonotactics, such as dispreferences for the occurrence of multiple voiced obstruents or sequential homorganic voiceless obstruents within stems. 2. Data: Rendaku in surnames 2.1. Strong Lyman’s Law? Rendaku, or sequential voicing (Martin, 1952), is a morphophonological process in Japanese whereby the initial obstruent of the second element of a compound becomes voiced,1 as shown in (1).2 (1) a. maki + susi ! maki-zusi ‘rolled-sushi’ b. ori + kami ! ori-gami ‘folding-paper’ Application of rendaku is variable, being affected by a number of factors including lexical idiosyncrasy (see Vance, 2015 for a comprehensive overview). -

L1 English Vocalic Transfer in L2 Japanese

L1 ENGLISH VOCALIC TRANSFER IN L2 JAPANESE by KENNETH JEFFREY KNIGHT (Under the Direction of Don R. McCreary) ABSTRACT This study looks at four factors that cause transfer errors in the duration and quality of vowel sounds in Japanese as spoken by native English speaking learners. These factors are: 1) words contain a contrastive long vowel, 2) words contain vowels in hiatal position, 3) words are English loanwords, and 4) words are written in Romanization. 34 students at the University of Georgia completed elicited imitation and reading aloud tasks. Results show that roughly 5% of all responses contained vocalic errors. Error rates were highest for minimal pairs that contrast only in vowel length. Similarities in orthography, word origin, and differences in phonological rules were shown to be significant factors in L2 Japanese vowel pronunciation error. A brief survey of the most widely used Japanese textbooks in the US reveals a lack of explicit instruction in vowel length contrasts and Japanese loanword adaptation. Increased explicit instruction in these areas as well as limited use of Romanization may greatly reduce the risk of L2 Japanese vowel pronunciation error. INDEX WORDS: Transfer; Interference; Japanese as a Foreign Language; English; Vowel; Duration; Second Language Acquisition L1 ENGLISH VOCALIC TRANSFER IN L2 JAPANESE by KENNETH JEFFREY KNIGHT B.A., Temple University, 1998 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ATHENS, GEORGIA 2013 © 2013 Kenneth Jeffrey Knight All Rights Reserved L1 ENGLISH VOCALIC TRANSFER IN L2 JAPANESE by KENNETH JEFFREY KNIGHT Major Professor: Don R. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ GEMINATED LIQUIDS in JAPANESE: a PRODUCTION STUDY a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisf

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ GEMINATED LIQUIDS IN JAPANESE: A PRODUCTION STUDY A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in LINGUISTICS by Maho Morimoto March 2020 The Dissertation of Maho Morimoto is approved: Grant McGuire, Chair Jaye Padgett Ryan Bennett Quentin Williams Acting Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Maho Morimoto 2020 Contents List of Figures vi List of Tables ix Abstract xvi Dedication xviii Acknowledgments xix 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Introduction . .1 1.2 Japanese phonology . .2 1.2.1 Vowel and consonant inventories . .2 1.2.2 Morpheme classes and lexical domains . .2 1.2.3 Geminates in Japanese . .3 1.2.4 Liquid consonant in Japanese . .6 1.3 Geminated liquids in Japanese . 11 1.3.1 Avoidance of geminated liquids . 11 1.3.2 Appearance of geminated liquids . 13 1.3.3 Issues in geminated liquids . 15 1.4 Outline of the dissertation . 17 2 Acoustic Characteristics of Geminated Liquids in Japanese 18 2.1 Introduction . 18 2.1.1 Acoustic characteristics of liquids . 19 2.1.2 Acoustic characteristics of geminates . 21 2.2 Method . 24 2.2.1 Subjects . 24 2.2.2 Speech materials . 25 2.2.3 Procedure . 28 2.2.4 Measurements . 29 iii 2.3 Durational results & discussion . 30 2.3.1 Consonant duration . 30 2.3.2 Preceding vowel duration . 34 2.3.3 Following vowel duration . 37 2.3.4 VCV duration . 40 2.3.5 Discussion . 42 2.4 Non-durational results & discussion . 43 2.4.1 Intensity on the consonants . -

Loanword Accentuation in Japanese

University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 11 Issue 1 Article 16 2005 Loanword accentuation in Japanese MASAHIKO MUTSUKAWA Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl Recommended Citation MUTSUKAWA, MASAHIKO (2005) "Loanword accentuation in Japanese," University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: Vol. 11 : Iss. 1 , Article 16. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol11/iss1/16 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol11/iss1/16 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Loanword accentuation in Japanese This working paper is available in University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol11/iss1/16 Loanword Accentuation in Japanese Masahiko Mutsukawa 1 Introduction Accentuation is one of the main issues in Japanese loanword phonology and many studies have been conducted. Most of the studies pursued so far, how ever, are on loanword accentuation in Tokyo Japanese, and loanword accen tuation in other dialects such as Kansai1 Japanese have been studied little. The present study analyzes the location of accent and the pitch pattern of accented English loanwords in both Tokyo Japanese and Kansai Japanese in the framework of Optimality Theory (OT; Prince and Smolensky, 1993). The major findings of this study are as follows. First, Tokyo Japanese and Kansai Japanese are the same in terms of accent assignment. The default accent of loanwords is the English accent, i.e. the accent on the syllable stressed in English. Second, Tokyo Japanese and Kansai Japanese are differ ent with regard to pitch pattern. The constraints *[HH and *[LL, which are members of the constraint family Obligatory Contour Principle (OCP), play crucial roles in Tokyo Japanese, while the constraints *[LL and LH' are sig nificant in Kansai Japanese. -

What /R/ Sounds Like in Kansai Japanese: a Phonetic Investigation of Liquid Variation in Unscripted Discourse

What /r/ Sounds Like in Kansai Japanese: A Phonetic Investigation of Liquid Variation in Unscripted Discourse by Thomas Judd Magnuson B.A., University of British Columbia, 1998 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Linguistics © Thomas Judd Magnuson, 2008 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii What /r/ Sounds Like in Kansai Japanese: A Phonetic Investigation of Liquid Variation in Unscripted Discourse by Thomas Judd Magnuson B.A., University of British Columbia, 1998 SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE Dr. Hua Lin, Supervisor (Department of Linguistics) Dr. John H. Esling, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) Dr. Tae-Jin Yoon, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) iii Supervisory Committee Dr. Hua Lin, Supervisor (Department of Linguistics) Dr. John H. Esling, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) Dr. Tae-Jin Yoon, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) ABSTRACT Unlike Canadian English which has two liquid consonant phonemes, /ɹ, l/ (as in right and light ), Japanese is said to have a single liquid phoneme whose realization varies widely both among speakers and within the speech of individuals. Although variants of the /r/ sound in Japanese have been described as flaps, laterals, and weak plosives, research that has sought to quantitatively describe this phonetic variation has not yet been carried out. The aim of this thesis is to provide such quantification based on 1,535 instances of /r/ spoken by four individuals whose near-natural, unscripted conversations had been recorded as part of a larger corpus of unscripted Japanese maintained by Dr.