Harmony Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vowel Quality and Phonological Projection

i Vowel Quality and Phonological Pro jection Marc van Oostendorp PhD Thesis Tilburg University September Acknowledgements The following p eople have help ed me prepare and write this dissertation John Alderete Elena Anagnostop oulou Sjef Barbiers Outi BatEl Dorothee Beermann Clemens Bennink Adams Bo domo Geert Bo oij Hans Bro ekhuis Norb ert Corver Martine Dhondt Ruud and Henny Dhondt Jo e Emonds Dicky Gilb ers Janet Grijzenhout Carlos Gussenhoven Gert jan Hakkenb erg Marco Haverkort Lars Hellan Ben Hermans Bart Holle brandse Hannekevan Ho of Angeliek van Hout Ro eland van Hout Harry van der Hulst Riny Huybregts Rene Kager HansPeter Kolb Emiel Krah mer David Leblanc Winnie Lechner Klarien van der Linde John Mc Carthy Dominique Nouveau Rolf Noyer Jaap and Hannyvan Oosten dorp Paola Monachesi Krisztina Polgardi Alan Prince Curt Rice Henk van Riemsdijk Iggy Ro ca Sam Rosenthall Grazyna Rowicka Lisa Selkirk Chris Sijtsma Craig Thiersch MiekeTrommelen Rub en van der Vijver Janneke Visser Riet Vos Jero en van de Weijer Wim Zonneveld Iwant to thank them all They have made the past four years for what it was the most interesting and happiest p erio d in mylife until now ii Contents Intro duction The Headedness of Syllables The Headedness Hyp othesis HH Theoretical Background Syllable Structure Feature geometry Sp ecication and Undersp ecicati on Skeletal tier Mo del of the grammar Optimality Theory Data Organisation of the thesis Chapter Chapter -

1 Consonant Harmony in Child Language

1 Consonant Harmony in Child Language: An Optimality-theoretic Account* Heather Goad Department of Linguistics, McGill University [email protected] Ms. dated 1995. Currently in press in S.J. Hannahs & M. Young-Scholten Focus on phonological acquisition. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 113-142. Abstract An analysis is provided of the consonant harmony (CH) patterns exhibited in the speech of one child, Amahl at Stage 1 (data from Smith 1973). It is argued that the standard rule-based analysis which involves Coronal underspecification and planar segregation is not tenable. First, the data reveal an underspecification paradox: coronal consonants are targets for CH and should thus be unspecified for Coronal. However, they also trigger harmony, in words where the targets are liquids. Second, the data are not consistent with planar segregation, as one harmony pattern is productive beyond the point when AmahlÕs grammar satisfies the requirements for planar segregation (set forth in McCarthy 1989). An alternative analysis is proposed within the constraint-based framework of Optimality Theory (Prince & Smolensky 1993). It is argued that CH follows from the relative ranking of constraints which parse place features and those which align features with the edges of the prosodic word. With the constraints responsible for parsing and aligning Labial and Dorsal ranked above those responsible for parsing and aligning Coronal, the dual behaviour of coronals can be captured. The effect of planar segregation follows from other independently motivated constraints which force alignment to be satisfied through copying of segmental material, not through spreading. Keywords: first language acquisition, consonant harmony, underspecification paradox 1. -

Repercussions of the History of a Typological Change in Germanic

Repercussions of the history of a typological change in Germanic. Roland Noske Université Lille 3 / CNRS UMR 8163 [email protected] Abstract. In acoustic experimental phonetic investigations, the distinction made by Pike (1945) and Abercrombie (1967) between syllable-timed and stress timed has been refuted on several occasions. (e.g. by Wenk and Wioland 1982). However, perceptual research (Dauer 1983, 1987) has given rise to re-instalment of this typology by Auer (1993, 2001). Auer proposes a gradual, multi-factorial typology between syllable counting languages (also called simply syllable languages) and stress counting languages (or word languages). In this typology, several indicators are used for positioning a language on the continuous scale between the syllable language prototype and the word language prototype. These indicators include, among others, complexity of syllable structure, the occurrence of geminate clusters, tonality, tonal phenomena, the occurrence of vowel harmony or metaphony, epenthesis, vowel deletion, liaison, the occurrence of internal and external sandhi, as well as morphological reanalyses. In this paper, this typology will be used to show that in the course of time, most West- Germanic dialects have moved gradually from the syllable type to the word type. Evidence for this comes from research done on Old High German and Midlle High German texts, as well as from German dialectology. It will be shown that the contrast between Northern an Southern Dutch with respect to liaison across word boundaries and the vowel deletion promoting regular syllable structure (both indicators for syllable language-hood), is not the result of a French influence (as assumed by Noske (2005, 2006, 2007). -

The Phonetics-Phonology Interface in Romance Languages José Ignacio Hualde, Ioana Chitoran

Surface sound and underlying structure : The phonetics-phonology interface in Romance languages José Ignacio Hualde, Ioana Chitoran To cite this version: José Ignacio Hualde, Ioana Chitoran. Surface sound and underlying structure : The phonetics- phonology interface in Romance languages. S. Fischer and C. Gabriel. Manual of grammatical interfaces in Romance, 10, Mouton de Gruyter, pp.23-40, 2016, Manuals of Romance Linguistics, 978-3-11-031186-0. hal-01226122 HAL Id: hal-01226122 https://hal-univ-paris.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01226122 Submitted on 24 Dec 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Manual of Grammatical Interfaces in Romance MRL 10 Brought to you by | Université de Paris Mathematiques-Recherche Authenticated | [email protected] Download Date | 11/1/16 3:56 PM Manuals of Romance Linguistics Manuels de linguistique romane Manuali di linguistica romanza Manuales de lingüística románica Edited by Günter Holtus and Fernando Sánchez Miret Volume 10 Brought to you by | Université de Paris Mathematiques-Recherche Authenticated | [email protected] Download Date | 11/1/16 3:56 PM Manual of Grammatical Interfaces in Romance Edited by Susann Fischer and Christoph Gabriel Brought to you by | Université de Paris Mathematiques-Recherche Authenticated | [email protected] Download Date | 11/1/16 3:56 PM ISBN 978-3-11-031178-5 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-031186-0 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-039483-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. -

Turkish Vowel Harmony: Underspecification, Iteration, Multiple Rules

Turkish vowel harmony: Underspecification, iteration, multiple rules LING 451/551 Spring 2011 Prof. Hargus Data • Turkish data on handout. [a] represents a low back unrounded vowel (more standardly [ɑ]). Morphological analysis and morpheme alternants • Words in Turkish – root alone – root followed by one or two suffixes • Suffixes – plural suffix, -[ler] ~ -[lar] – genitive suffix, -[in] ~ -[un] ~ -[ün] ~ -[ɨn] • Order of morphemes – root - plural - genitive Possible vowel features i ɨ u ü e a o ö high + + + + - - - - low - - - - - + - - back - + + - - + + - front + - - + + - - + round - - + + - - + + Distinctive features of vowels i ɨ u ü e a o ö high + + + + - - - - back - + + - - + + - round - - + + - - + + ([front] could be used instead of [back].) Values of [low] are redundant: V -high [+low] +back -round Otherwise: V [-low] Distribution of suffix alternants • Plural suffix – -[ler] / front vowels C(C) ___ – -[lar] / back vowels C(C) ___ • Genitive suffix – -[in] / front non-round vowels C(C) ___ – -[ün] / front round vowels C(C) ___ – -[ɨn] / back non-round vowels C(C) ___ – -[un] / back round vowels C(C) ___ Subscript and superscript convention • C1 = one or more consonants: C, CC, CCC, etc. • C0 = zero or more consonants: 0, C, CC, CCC, etc. • C1 = at most one consonant: 0, C 2 • C1 = minimum one, maximum 2 C: C(C) Analysis of alternating morphemes • Symmetrical distribution of suffix alternants • No non-alternating suffixes No single suffix alternant can be elevated to UR URs • UR = what all suffixes have in common • genitive: -/ V n/ [+high] (values of [back] and [round] will be added to match preceding vowel) an underspecified vowel, or ―archiphoneme‖ (Odden p. 239) Backness Harmony • Both high and non-high suffixes assimilate in backness to a preceding vowel • Backness Harmony: V --> [+ back] / V C0 ____ [+back] V --> [-back] / V C0 ____ [-back] (―collapsed‖) V --> [ back] / V C0 ____ [ back] (This is essentially the same as Hayes‘ [featurei].. -

Sociophonetic Variation in Bolivian Quechua Uvular Stops

Title Page Sociophonetic Variation in Bolivian Quechua Uvular Stops by Eva Bacas University of Pittsburgh, 2019 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2019 Committee Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This thesis was presented by Eva Bacas It was defended on November 8, 2019 and approved by Alana DeLoge, Quechua Instructor, Department of Linguistics, University of Pittsburgh Melinda Fricke, Assistant Professor, Department of Linguistics, University of Pittsburgh Gillian Gallagher, Associate Professor, Department of Linguistics, New York University Thesis Advisor/Dissertation Director: Claude Mauk, Senior Lecturer, Department of Linguistics, University of Pittsburgh ii Copyright © by Eva Bacas 2019 iii Abstract Sociophonetic Variation in Bolivian Quechua Uvular Stops Eva Bacas, BPhil University of Pittsburgh, 2019 Quechua is an indigenous language of the Andes region of South America. In Cochabamba, Bolivia, Quechua and Spanish have been in contact for over 500 years. In this thesis, I explore sociolinguistic variation among bilingual speakers of Cochabamba Quechua (CQ) and Spanish by investigating the relationship between the production of the voiceless uvular stop /q/ and speakers’ sociolinguistic backgrounds. I conducted a speech production study and sociolinguistic interview with seven bilingual CQ-Spanish speakers. I analyzed manner of articulation and place of articulation variation. Results indicate that manner of articulation varies primarily due to phonological factors, and place of articulation varies according to sociolinguistic factors. This reveals that among bilingual CQ-Spanish speakers, production of voiceless uvular stop /q/ does vary sociolinguistically. -

Recognition of Nasalized and Non- Nasalized Vowels

RECOGNITION OF NASALIZED AND NON- NASALIZED VOWELS Submitted By: BILAL A. RAJA Advised by: Dr. Carol Espy Wilson and Tarun Pruthi Speech Communication Lab, Dept of Electrical & Computer Engineering University of Maryland, College Park Maryland Engineering Research Internship Teams (MERIT) Program 2006 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1- Abstract 3 2- What Is Nasalization? 3 2.1 – Production of Nasal Sound 3 2.2 – Common Spectral Characteristics of Nasalization 4 3 – Expected Results 6 3.1 – Related Previous Researches 6 3.2 – Hypothesis 7 4- Method 7 4.1 – The Task 7 4.2 – The Technique Used 8 4.3 – HMM Tool Kit (HTK) 8 4.3.1 – Data Preparation 9 4.3.2 – Training 9 4.3.3 – Testing 9 4.3.4 – Analysis 9 5 – Results 10 5.1 – Experiment 1 11 5.2 – Experiment 2 11 6 – Conclusion 12 7- References 13 2 1 - ABSTRACT When vowels are adjacent to nasal consonants (/m,n,ng/), they often become nasalized for at least some part of their duration. This nasalization is known to lead to changes in perceived vowel quality. The goal of this project is to verify if it is beneficial to first recognize nasalization in vowels and treat the three groups of vowels (those occurring before nasal consonants, those occurring after nasal consonants, and the oral vowels which are vowels that are not adjacent to nasal consonants) separately rather than collectively for recognizing the vowel identities. The standard Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs) and the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) paradigm have been used for this purpose. The results show that when the system is trained on vowels in general, the recognition of nasalized vowels is 17% below that of oral vowels. -

Phonemic Vs. Derived Glides

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/240419751 Phonemic vs. derived glides ARTICLE in LINGUA · DECEMBER 2008 Impact Factor: 0.71 · DOI: 10.1016/j.lingua.2007.10.003 CITATIONS READS 14 32 1 AUTHOR: Susannah V Levi New York University 24 PUBLICATIONS 172 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Available from: Susannah V Levi Retrieved on: 09 October 2015 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Lingua 118 (2008) 1956–1978 www.elsevier.com/locate/lingua Phonemic vs. derived glides Susannah V. Levi * Department of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology, New York University, 665 Broadway, 9th Floor, New York, NY 10003, United States Received 2 February 2007; received in revised form 30 June 2007; accepted 2 October 2007 Available online 27 September 2008 Abstract Previous accounts of glides have argued that all glides are derived from vowels. In this paper, we examine data from Karuk, Sundanese, and Pulaar which reveal the existence of two types of phonologically distinct glides both cross-linguistically and within a single language. ‘‘Phonemic’’ glides are distinct from underlying vowels and pattern with other sonorant consonants, while ‘‘derived’’ glides are non-syllabic, positional variants of underlying vowels and exhibit vowel-like behavior. It is argued that the phonological difference between these two types of glides lies in their different underlying featural representations. Derived glides are positional variants of vowels and therefore featurally identical. In contrast, phonemic glides are featurally distinct from underlying vowels and therefore pattern differently. Though a phono- logical distinction between these two types of glides is evident in these three languages, a reliable phonetic distinction does not appear to exist. -

5 Phonology Florian Lionnet and Larry M

5 Phonology Florian Lionnet and Larry M. Hyman 5.1. Introduction The historical relation between African and general phonology has been a mutu- ally beneficial one: the languages of the African continent provide some of the most interesting and, at times, unusual phonological phenomena, which have con- tributed to the development of phonology in quite central ways. This has been made possible by the careful descriptive work that has been done on African lan- guages, by linguists and non-linguists, and by Africanists and non-Africanists who have peeked in from time to time. Except for the click consonants of the Khoisan languages (which spill over onto some neighboring Bantu languages that have “borrowed” them), the phonological phenomena found in African languages are usually duplicated elsewhere on the globe, though not always in as concen- trated a fashion. The vast majority of African languages are tonal, and many also have vowel harmony (especially vowel height harmony and advanced tongue root [ATR] harmony). Not surprisingly, then, African languages have figured dispro- portionately in theoretical treatments of these two phenomena. On the other hand, if there is a phonological property where African languages are underrepresented, it would have to be stress systems – which rarely, if ever, achieve the complexity found in other (mostly non-tonal) languages. However, it should be noted that the languages of Africa have contributed significantly to virtually every other aspect of general phonology, and that the various developments of phonological theory have in turn often greatly contributed to a better understanding of the phonologies of African languages. Given the considerable diversity of the properties found in different parts of the continent, as well as in different genetic groups or areas, it will not be possible to provide a complete account of the phonological phenomena typically found in African languages, overviews of which are available in such works as Creissels (1994) and Clements (2000). -

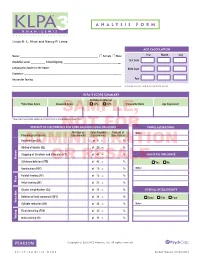

Sample, Not for Administration Or Resale

ANALYSIS FORM Linda M. L. Khan and Nancy P. Lewis Age Calculation Name: ______________________________________________________ u Female u Male Year Month Day Test Date Grade/Ed. Level: __________ School/Agency: __________________________________________ Language(s) Spoken in the Home: ___________________________________________________ Birth Date Examiner: ____________________________________________________________________ Reason for Testing: ______________________________________________________________ Age ____________________________________________________________________________ Reminder: Do not round up to next month or year. KLPA–3 Score Summary Confidence Interval *Total Raw Score Standard Score 90% 95% Percentile Rank Age Equivalent SAMPLE,– * Raw score equals total number of occurrences of scored phonological processes. Percent of OccurrenceNOT for Core Phonological ProcessesFOR Vowel Alterations Number of Total Possible Percent of Notes: Phonological Process Occurrences Occurrences Occurrences DeaffricationADMINISTRATION (DF) of 8 = % Gliding of liquids (GL) of 20 = % Stopping of fricatives and affricates (ST) of 48 = % Dialectal Influence Manner OR RESALE Stridency deletion (STR) of 42 = % Yes No Vocalization (VOC) of 15 = % Notes: Palatal fronting (PF) of 12 = % Place Velar fronting (VF) of 23 = % Cluster simplification (CS) of 23 = % Overall Intelligibility Deletion of final consonant (DFC) of 36 = % Good Fair Poor Reduction Syllable reduction (SR) of 25 = % Notes: Final devoicing (FDV) of 35 = % Voicing Initial voicing -

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin Essay Title: The sound system of Japanese This essay aims to introduce the sound system of Japanese, including the inventories of consonants, vowels, and diphthongs. The phonological variations of the sound segments in different phonetic environments are also included. For the illustration, word examples are given and they are presented in the following format: [IPA] (Romaji: “meaning”). Consonants In Japanese, there are 14 core consonants, and some of them have a lot of allophonic variations. The various types of consonants classified with respect to their manner of articulation are presented as follows. Stop Japanese has six oral stops or plosives, /p b t d k g/, which are classified into three place categories, bilabial, alveolar, and velar, as listed below. In each place category, there is a pair of plosives with the contrast in voicing. /p/ = a voiceless bilabial plosive [p]: [ippai] (ippai: “A cup of”) /b/ = a voiced bilabial plosive [b]: [baɴ] (ban: “Night”) /t/ = a voiceless alveolar plosive [t]: [oto̞ ːto̞ ] (ototo: “Brother”) /d/ = a voiced alveolar plosive [d]: [to̞ mo̞ datɕi] (tomodachi: “Friend”) /k/ = a voiceless velar plosive [k]: [kaiɰa] (kaiwa: “Conversation”) /g/ = a voiced velar plosive [g]: [ɡakɯβsai] (gakusai: “Student”) Phonetically, Japanese also has a glottal stop [ʔ] which is commonly produced to separate the neighboring vowels occurring in different syllables. This phonological phenomenon is known as ‘glottal stop insertion’. The glottal stop may be realized as a pause, which is used to indicate the beginning or the end of an utterance. For instance, the word “Japanese money” is actually pronounced as [ʔe̞ ɴ], instead of [je̞ ɴ], and the pronunciation of “¥15” is [dʑɯβːɡo̞ ʔe̞ ɴ]. -

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics Title The Aeroacoustics of Nasalized Fricatives Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/00h9g9gg Author Shosted, Ryan K Publication Date 2006 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Aeroacoustics of Nasalized Fricatives by Ryan Keith Shosted B.A. (Brigham Young University) 2000 M.A. (University of California, Berkeley) 2003 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: John J. Ohala, Chair Keith Johnson Milton M. Azevedo Fall 2006 The dissertation of Ryan Keith Shosted is approved: Chair Date Date Date University of California, Berkeley Fall 2006 The Aeroacoustics of Nasalized Fricatives Copyright 2006 by Ryan Keith Shosted 1 Abstract The Aeroacoustics of Nasalized Fricatives by Ryan Keith Shosted Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley John J. Ohala, Chair Understanding the relationship of aerodynamic laws to the unique geometry of the hu- man vocal tract allows us to make phonological and typological predictions about speech sounds typified by particular aerodynamic regimes. For example, some have argued that the realization of nasalized fricatives is improbable because fricatives and nasals have an- tagonistic aerodynamic specifications. Fricatives require high pressure behind the suprala- ryngeal constriction as a precondition for high particle velocity. Nasalization, on the other hand, vents back pressure by allowing air to escape through the velopharyngeal orifice. This implies that an open velopharyngeal port will reduce oral particle velocity, thereby potentially extinguishing frication. By using a mechanical model of the vocal tract and spoken fricatives that have undergone coarticulatory nasalization, it is shown that nasal- ization must alter the spectral characteristics of fricatives, e.g.