An Introduction to English Phonology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Modern English

Mrs. Halverson: English 9A Intro to Shakespeare’s Language: Early Modern English Romeo and Juliet was written around 1595, when William Shakespeare was about 31 years old. In Shakespeare's day, England was just barely catching up to the Renaissance that had swept over Europe beginning in the 1400s. But England's theatrical performances soon put the rest of Europe to shame. Everyone went to plays, and often more than once a week. There you were not only entertained but also exposed to an explosion of new phrases and words entering the English language for overseas and from the creative minds of Shakespeare and his contemporaries. The language Shakespeare uses in his plays is known as Early Modern English, and is approximately contemporaneous with the writing of the King James Bible. Believe it or not, much of Shakespeare's vocabulary is still in use today. For instance, Howard Richler in Take My Words noted the following phrases originated with Shakespeare: without rhyme or reason flesh and blood in a pickle with bated breath vanished into thin air budge an inch more sinned against than sinning fair play playing fast and loose brevity is the soul of wit slept a wink foregone conclusion breathing your last dead as a door-nail point your finger the devil incarnate send me packing laughing-stock bid me good riddance sorry sight heart of gold come full circle Nonetheless, Shakespeare does use words or forms of words that have gone out of use. Here are some guidelines: 1) Shakespeare uses some personal pronouns that have become archaic. -

Influences on the Development of Early Modern English

Influences on the Development of Early Modern English Kyli Larson Wright This article covers the basic social, historical, and linguistic influences that have transformed the English language. Research first describes components of Early Modern English, then discusses how certain factors have altered the lexicon, phonology, and other components. Though there are many factors that have shaped English to what it is today, this article only discusses major factors in simple and straightforward terms. 72 Introduction The history of the English language is long and complicated. Our language has shifted, expanded, and has eventually transformed into the lingua franca of the modern world. During the Early Modern English period, from 1500 to 1700, countless factors influenced the development of English, transforming it into the language we recognize today. While the history of this language is complex, the purpose of this article is to determine and map out the major historical, social, and linguistic influences. Also, this article helps to explain the reasons for their influence through some examples and evidence of writings from the Early Modern period. Historical Factors One preliminary historical event that majorly influenced the development of the language was the establishment of the print- ing press. Created in 1476 by William Caxton at Westminster, London, the printing press revolutionized the current language form by creating a means for language maintenance, which helped English gravitate toward a general standard. Manuscripts could be reproduced quicker than ever before, and would be identical copies. Because of the printing press spelling variation would eventually decrease (it was fixed by 1650), especially in re- ligious and literary texts. -

Phonological Theories Autosegmental/Metrical Phonology

Phonological Theories Autosegmental/Metrical Phonology Session 6 Phonological Theories Non-linear stress allocation Metrical phonology was an approach to word, phrase and sentence-stress definition which (a) defined stress as a syllabic property, not a vowel-inherent feature, and allowed a more flexible treatment of stress patterns in i) different languages, ii) different phrase-prosodic contexts. The prominence relations between syllables are defined by a (binary branching) tree, where the two branches from a node are labelled as dominant (s = strong) and recessive (w = weak) in their relation to each other. Four (quasi-independent) choices (are assumed to) determine the stress patterns that (appear to) exist in natural languages: 1 Right-dominant-foot vs. left-dominant-foot languages 2 Bounded vs. unbounded stress 3 Left-to-right vs. right-to-left word-stress assignment 4 Quantity-sensitive vs. quantity-insensitive languages Phonological Theories Right-dominant vs. left-dominant Languages differ in the tendency for the feet to have the strong syllable on the right or the left: Fr. sympho"nie fantas"tique Engl. "Buckingham "Palace F F F F s s s w w s w w s s w w s w Phonological Theories Bounded vs. unbounded stress (1) “Bounded” (vs. “unbounded”) is a concept that applies to the number of subordinate units that can be dominated by a higher node In metrical phonology it applies usually to the number of syllables that can be dominated by a Foot node (bounded = 2; one strong, one weak syllable to the left or the right; unbounded = no limit). This implies that bounded-stress languages have binary feet. -

The Past, Present, and Future of English Dialects: Quantifying Convergence, Divergence, and Dynamic Equilibrium

Language Variation and Change, 22 (2010), 69–104. © Cambridge University Press, 2010 0954-3945/10 $16.00 doi:10.1017/S0954394510000013 The past, present, and future of English dialects: Quantifying convergence, divergence, and dynamic equilibrium WARREN M AGUIRE AND A PRIL M C M AHON University of Edinburgh P AUL H EGGARTY University of Cambridge D AN D EDIU Max-Planck-Institute for Psycholinguistics ABSTRACT This article reports on research which seeks to compare and measure the similarities between phonetic transcriptions in the analysis of relationships between varieties of English. It addresses the question of whether these varieties have been converging, diverging, or maintaining equilibrium as a result of endogenous and exogenous phonetic and phonological changes. We argue that it is only possible to identify such patterns of change by the simultaneous comparison of a wide range of varieties of a language across a data set that has not been specifically selected to highlight those changes that are believed to be important. Our analysis suggests that although there has been an obvious reduction in regional variation with the loss of traditional dialects of English and Scots, there has not been any significant convergence (or divergence) of regional accents of English in recent decades, despite the rapid spread of a number of features such as TH-fronting. THE PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE OF ENGLISH DIALECTS Trudgill (1990) made a distinction between Traditional and Mainstream dialects of English. Of the Traditional dialects, he stated (p. 5) that: They are most easily found, as far as England is concerned, in the more remote and peripheral rural areas of the country, although some urban areas of northern and western England still have many Traditional Dialect speakers. -

Nigel Fabb and Morris Halle (2008), Meter in Poetry

Nigel Fabb and Morris Halle (2008), Meter in Poetry Paul Kiparsky Stanford University [email protected] Linguistics Department, Stanford University, CA. 94305-2150 July 19, 2009 Review (4872 words) The publication of this joint book by the founder of generative metrics and a distinguished literary linguist is a major event.1 F&H take a fresh look at much familiar material, and introduce an eye-opening collection of metrical systems from world literature into the theoretical discourse. The complex analyses are clearly presented, and illustrated with detailed derivations. A guest chapter by Carlos Piera offers an insightful survey of Southern Romance metrics. Like almost all versions of generative metrics, F&H adopt the three-way distinction between what Jakobson called VERSE DESIGN, VERSE INSTANCE, and DELIVERY INSTANCE.2 F&H’s the- ory maps abstract grid patterns onto the linguistically determined properties of texts. In that sense, it is a kind of template-matching theory. The mapping imposes constraints on the distribution of texts, which define their metrical form. Recitation may or may not reflect meter, according to conventional stylized norms, but the meter of a text itself is invariant, however it is pronounced or sung. Where F&H differ from everyone else is in denying the centrality of rhythm in meter, and char- acterizing the abstract templates and their relationship to the text by a combination of constraints and processes modeled on Halle/Idsardi-style metrical phonology. F&H say that lineation and length restrictions are the primary property of verse, and rhythm is epiphenomenal, “a property of the way a sequence of words is read or performed” (p. -

Laryngeal Features in German* Michael Jessen Bundeskriminalamt, Wiesbaden Catherine Ringen University of Iowa

Phonology 19 (2002) 189–218. f 2002 Cambridge University Press DOI: 10.1017/S0952675702004311 Printed in the United Kingdom Laryngeal features in German* Michael Jessen Bundeskriminalamt, Wiesbaden Catherine Ringen University of Iowa It is well known that initially and when preceded by a word that ends with a voiceless sound, German so-called ‘voiced’ stops are usually voiceless, that intervocalically both voiced and voiceless stops occur and that syllable-final (obstruent) stops are voiceless. Such a distribution is consistent with an analysis in which the contrast is one of [voice] and syllable-final stops are devoiced. It is also consistent with the view that in German the contrast is between stops that are [spread glottis] and those that are not. On such a view, the intervocalic voiced stops arise because of passive voicing of the non-[spread glottis] stops. The purpose of this paper is to present experimental results that support the view that German has underlying [spread glottis] stops, not [voice] stops. 1 Introduction In spite of the fact that voiced (obstruent) stops in German (and many other Germanic languages) are markedly different from voiced stops in languages like Spanish, Russian and Hungarian, all of these languages are usually claimed to have stops that contrast in voicing. For example, Wurzel (1970), Rubach (1990), Hall (1993) and Wiese (1996) assume that German has underlying voiced stops in their different accounts of Ger- man syllable-final devoicing in various rule-based frameworks. Similarly, Lombardi (1999) assumes that German has underlying voiced obstruents in her optimality-theoretic (OT) account of syllable-final laryngeal neutralisation and assimilation in obstruent clusters. -

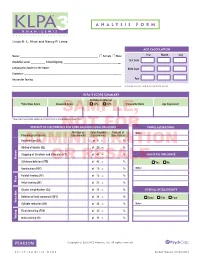

Sample, Not for Administration Or Resale

ANALYSIS FORM Linda M. L. Khan and Nancy P. Lewis Age Calculation Name: ______________________________________________________ u Female u Male Year Month Day Test Date Grade/Ed. Level: __________ School/Agency: __________________________________________ Language(s) Spoken in the Home: ___________________________________________________ Birth Date Examiner: ____________________________________________________________________ Reason for Testing: ______________________________________________________________ Age ____________________________________________________________________________ Reminder: Do not round up to next month or year. KLPA–3 Score Summary Confidence Interval *Total Raw Score Standard Score 90% 95% Percentile Rank Age Equivalent SAMPLE,– * Raw score equals total number of occurrences of scored phonological processes. Percent of OccurrenceNOT for Core Phonological ProcessesFOR Vowel Alterations Number of Total Possible Percent of Notes: Phonological Process Occurrences Occurrences Occurrences DeaffricationADMINISTRATION (DF) of 8 = % Gliding of liquids (GL) of 20 = % Stopping of fricatives and affricates (ST) of 48 = % Dialectal Influence Manner OR RESALE Stridency deletion (STR) of 42 = % Yes No Vocalization (VOC) of 15 = % Notes: Palatal fronting (PF) of 12 = % Place Velar fronting (VF) of 23 = % Cluster simplification (CS) of 23 = % Overall Intelligibility Deletion of final consonant (DFC) of 36 = % Good Fair Poor Reduction Syllable reduction (SR) of 25 = % Notes: Final devoicing (FDV) of 35 = % Voicing Initial voicing -

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin Essay Title: The sound system of Japanese This essay aims to introduce the sound system of Japanese, including the inventories of consonants, vowels, and diphthongs. The phonological variations of the sound segments in different phonetic environments are also included. For the illustration, word examples are given and they are presented in the following format: [IPA] (Romaji: “meaning”). Consonants In Japanese, there are 14 core consonants, and some of them have a lot of allophonic variations. The various types of consonants classified with respect to their manner of articulation are presented as follows. Stop Japanese has six oral stops or plosives, /p b t d k g/, which are classified into three place categories, bilabial, alveolar, and velar, as listed below. In each place category, there is a pair of plosives with the contrast in voicing. /p/ = a voiceless bilabial plosive [p]: [ippai] (ippai: “A cup of”) /b/ = a voiced bilabial plosive [b]: [baɴ] (ban: “Night”) /t/ = a voiceless alveolar plosive [t]: [oto̞ ːto̞ ] (ototo: “Brother”) /d/ = a voiced alveolar plosive [d]: [to̞ mo̞ datɕi] (tomodachi: “Friend”) /k/ = a voiceless velar plosive [k]: [kaiɰa] (kaiwa: “Conversation”) /g/ = a voiced velar plosive [g]: [ɡakɯβsai] (gakusai: “Student”) Phonetically, Japanese also has a glottal stop [ʔ] which is commonly produced to separate the neighboring vowels occurring in different syllables. This phonological phenomenon is known as ‘glottal stop insertion’. The glottal stop may be realized as a pause, which is used to indicate the beginning or the end of an utterance. For instance, the word “Japanese money” is actually pronounced as [ʔe̞ ɴ], instead of [je̞ ɴ], and the pronunciation of “¥15” is [dʑɯβːɡo̞ ʔe̞ ɴ]. -

LANGUAGE VARIETY in ENGLAND 1 ♦ Language Variety in England

LANGUAGE VARIETY IN ENGLAND 1 ♦ Language Variety in England One thing that is important to very many English people is where they are from. For many of us, whatever happens to us in later life, and however much we move house or travel, the place where we grew up and spent our childhood and adolescence retains a special significance. Of course, this is not true of all of us. More often than in previous generations, families may move around the country, and there are increasing numbers of people who have had a nomadic childhood and are not really ‘from’ anywhere. But for a majority of English people, pride and interest in the area where they grew up is still a reality. The country is full of football supporters whose main concern is for the club of their childhood, even though they may now live hundreds of miles away. Local newspapers criss-cross the country in their thousands on their way to ‘exiles’ who have left their local areas. And at Christmas time the roads and railways are full of people returning to their native heath for the holiday period. Where we are from is thus an important part of our personal identity, and for many of us an important component of this local identity is the way we speak – our accent and dialect. Nearly all of us have regional features in the way we speak English, and are happy that this should be so, although of course there are upper-class people who have regionless accents, as well as people who for some reason wish to conceal their regional origins. -

Glossary of Key Terms

Glossary of Key Terms accent: a pronunciation variety used by a specific group of people. allophone: different phonetic realizations of a phoneme. allophonic variation: variations in how a phoneme is pronounced which do not create a meaning difference in words. alveolar: a sound produced near or on the alveolar ridge. alveolar ridge: the small bony ridge behind the upper front teeth. approximants: obstruct the air flow so little that they could almost be classed as vowels if they were in a different context (e.g. /w/ or /j/). articulatory organs – (or articulators): are the different parts of the vocal tract that can change the shape of the air flow. articulatory settings or ‘voice quality’: refers to the characteristic or long-term positioning of articulators by individual or groups of speakers of a particular language. aspirated: phonemes involve an auditory plosion (‘puff of air’) where the air can be heard passing through the glottis after the release phase. assimilation: a process where one sound is influenced by the characteristics of an adjacent sound. back vowels: vowels where the back part of the tongue is raised (like ‘two’ and ‘tar’) bilabial: a sound that involves contact between the two lips. breathy voice: voice quality where whisper is combined with voicing. cardinal vowels: a set of phonetic vowels used as reference points which do not relate to any specific language. central vowels: vowels where the central part of the tongue is raised (like ‘fur’ and ‘sun’) centring diphthongs: glide towards /ə/. citation form: the way we say a word on its own. close vowel: where the tongue is raised as close as possible to the roof of the mouth. -

What Are Mergers?

What are mergers? Warren Maguire (University of Edinburgh) Lynn Clark (Lancaster University) Kevin Watson (University of Canterbury) Example mergers • You’ll all have heard of the following (and many other phonological mergers besides): – the MEAT-MEET merger: the merger of Middle English / ɛː / and /e ː/ – the /o/ -/oh/ merger or COT -CAUGHT merger: the merger of English / ɒ/ (or / ɑ/) and / ɔː / – the NEAR-SQUARE merger: the merger of the vowel in words such as beer , fear , near with the vowel in words such as bare , fair , square • But what are these phenomena? – and why are they of considerable interest to linguists? Phonological merger • ‘Merger’ in these cases refers to loss or absence of phonological distinction • ‘Merger’ can refer to a property of a language, of variety of a language, or of a speech community – these are convenient cover terms for collections of individuals (and their phonologies) who are more or less similar • It can refer to a feature of an individual’s phonology – in comparison with those of other speakers Synchronic and diachronic merger • ‘Merger’ may refer to a synchronic state – absence of a historic distinction (which may still exist elsewhere) – in varieties – in individuals • Or to diachronic change – loss of a distinction over time – in varieties – can individuals lose distinctions? Synchronic merger • A complicating issue is that, though phonology is a cognitive state, speakers don’t live in vacuums but are exposed to other speech patterns which may be different than their own – how much knowledge -

Phonemic Instability: a Butterfly Effect

PHONEMIC INSTABILITY: A BUTTERFLY EFFECT PAROMA SANYAL REENA ASHEM Indian Institute of Technology-Delhi, India 1xxIntroduction Can an imperceptibly tiny change in the relative ranking of a markedness constraint lead to phonemic instability and ultimately sound change in a language? In this paper we predict that this could indeed be the case when the phonological processes that take place within a certain morpho-phonological domain result in a particular phoneme being reinterpreted as marked by new learners of the language. According to McCarthy and Prince (1994), The Emergence of the Unmarked is a generalization about markedness constraints that are otherwise invisible in a language becoming visible in certain marked domains. While a markedness constraint C 'in the language as a whole, may be roundly violated, but in a particular domain it is obeyed exactly.' Now imagine the scenario where a markedness constraint C is ranked so low in the language that it is invisible for all practical purposes. However, when the satisfaction of a complex set of well-formedness constraints within a marked domain coincides with a systematic violation of C, it is possible for new learners of the language to re-rank C higher in the language. Thus the surface realization of phonological well-formedness conditions, if coincidentally localized to particular phonemes, rather than being distributed over a range of environments, could trigger phonemic instability and eventual sound change in the language. The Tibeto-Burman language Meiteilon, spoken in the state of Manipur in India, we claim, has a similar reanalysis taking place in its current phonological grammar. Meiteilon, like most other Tibeto-Burman languages of the region has rich inflectional morphology that attaches as suffixes to monosyllabic nominal or verbal roots.