The Sounds of Spanish: Review Questions for Chapters 14-25

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vowel Quality and Phonological Projection

i Vowel Quality and Phonological Pro jection Marc van Oostendorp PhD Thesis Tilburg University September Acknowledgements The following p eople have help ed me prepare and write this dissertation John Alderete Elena Anagnostop oulou Sjef Barbiers Outi BatEl Dorothee Beermann Clemens Bennink Adams Bo domo Geert Bo oij Hans Bro ekhuis Norb ert Corver Martine Dhondt Ruud and Henny Dhondt Jo e Emonds Dicky Gilb ers Janet Grijzenhout Carlos Gussenhoven Gert jan Hakkenb erg Marco Haverkort Lars Hellan Ben Hermans Bart Holle brandse Hannekevan Ho of Angeliek van Hout Ro eland van Hout Harry van der Hulst Riny Huybregts Rene Kager HansPeter Kolb Emiel Krah mer David Leblanc Winnie Lechner Klarien van der Linde John Mc Carthy Dominique Nouveau Rolf Noyer Jaap and Hannyvan Oosten dorp Paola Monachesi Krisztina Polgardi Alan Prince Curt Rice Henk van Riemsdijk Iggy Ro ca Sam Rosenthall Grazyna Rowicka Lisa Selkirk Chris Sijtsma Craig Thiersch MiekeTrommelen Rub en van der Vijver Janneke Visser Riet Vos Jero en van de Weijer Wim Zonneveld Iwant to thank them all They have made the past four years for what it was the most interesting and happiest p erio d in mylife until now ii Contents Intro duction The Headedness of Syllables The Headedness Hyp othesis HH Theoretical Background Syllable Structure Feature geometry Sp ecication and Undersp ecicati on Skeletal tier Mo del of the grammar Optimality Theory Data Organisation of the thesis Chapter Chapter -

Perceptions of Dialect Standardness in Puerto Rican Spanish

Perceptions of Dialect Standardness in Puerto Rican Spanish Jonathan Roig Advisor: Jason Shaw Submitted to the faculty of the Department of Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Yale University May 2018 Abstract Dialect perception studies have revealed that speakers tend to have false biases about their own dialect. I tested that claim with Puerto Rican Spanish speakers: do they perceive their dialect as a standard or non-standard one? To test this question, based on the dialect perception work of Niedzielski (1999), I created a survey in which speakers of Puerto Rican Spanish listen to sentences with a phonological phenomenon specific to their dialect, in this case a syllable- final substitution of [R] with [l]. They then must match the sounds they hear in each sentence to one on a six-point continuum spanning from [R] to [l]. One-third of participants are told that they are listening to a Puerto Rican Spanish speaker, one-third that they are listening to a speaker of Standard Spanish, and one-third are told nothing about the speaker. When asked to identify the sounds they hear, will participants choose sounds that are more similar to Puerto Rican Spanish or more similar to the standard variant? I predicted that Puerto Rican Spanish speakers would identify sounds as less standard when told the speaker was Puerto Rican, and more standard when told that the speaker is a Standard Spanish speaker, despite the fact that the speaker is the same Puerto Rican Spanish speaker in all scenarios. Some effect can be found when looking at differences by age and household income, but the results of the main effect were insignificant (p = 0.680) and were therefore inconclusive. -

Language in the USA

This page intentionally left blank Language in the USA This textbook provides a comprehensive survey of current language issues in the USA. Through a series of specially commissioned chapters by lead- ing scholars, it explores the nature of language variation in the United States and its social, historical, and political significance. Part 1, “American English,” explores the history and distinctiveness of American English, as well as looking at regional and social varieties, African American Vernacular English, and the Dictionary of American Regional English. Part 2, “Other language varieties,” looks at Creole and Native American languages, Spanish, American Sign Language, Asian American varieties, multilingualism, linguistic diversity, and English acquisition. Part 3, “The sociolinguistic situation,” includes chapters on attitudes to language, ideology and prejudice, language and education, adolescent language, slang, Hip Hop Nation Language, the language of cyberspace, doctor–patient communication, language and identity in liter- ature, and how language relates to gender and sexuality. It also explores recent issues such as the Ebonics controversy, the Bilingual Education debate, and the English-Only movement. Clear, accessible, and broad in its coverage, Language in the USA will be welcomed by students across the disciplines of English, Linguistics, Communication Studies, American Studies and Popular Culture, as well as anyone interested more generally in language and related issues. edward finegan is Professor of Linguistics and Law at the Uni- versity of Southern California. He has published articles in a variety of journals, and his previous books include Attitudes toward English Usage (1980), Sociolinguistic Perspectives on Register (co-edited with Douglas Biber, 1994), and Language: Its Structure and Use, 4th edn. -

L1 Prosody Attrition Among Spanish-English Bilinguals

Running head: L1 PROSODY ATTRITION AMONG SPANISH-ENGLISH BILINGUALS L1 Prosody Attrition Among Colombian Spanish-English Bilinguals: A Case Study on Vowel Reduction Pieter Winnemuller (800183) Master’s Thesis Communication and Information Sciences Business Communication & Digital Media School of Humanities Tilburg University Supervisor: L. van Maastricht MA Second reader: Dr. E. Oversteegen December 2017 L1 PROSODY ATTRITION AMONG SPANISH-ENGLISH BILINGUALS Abstract The process of losing or changing the first language (L1) as a result of acquiring a second language (L2) is called L1 attrition. This phenomenon has been researched in many linguistic areas, yet a relatively underexposed research area is that on prosody (i.e., the rhythmic and melodic patterns that determine, for example, intonation, rhythm and stress placement). The current study investigated whether prosodic L1 attrition occurred in the speech of Sofía Vergara, a Colombian Spanish-English bilingual who has been living and working in an L2 environment for approximately two decades. A semi-automatic acoustic analysis was conducted to determine whether vowel reduction (i.e., producing unstressed vowels with a shorter duration and a different vowel quality than stressed vowels) occurred in her L1 Spanish speech to a greater extent than in the speech of Spanish monolinguals, as measured in earlier studies. The results from this analysis show that vowel reduction did occur in her L1 speech: the unstressed Spanish /a/, /i/ and /o/ vowels were significantly reduced in duration, and the unstressed /a/ and /e/ showed significant differences in vowel quality vis-à-vis stressed vowels. However, vowel reduction did not occur to a greater extent than in the speech of monolingual Spanish speakers. -

Coarticulation Between Aspirated-S and Voiceless Stops in Spanish: an Interdialectal Comparison

Coarticulation between Aspirated-s and Voiceless Stops in Spanish: An Interdialectal Comparison Francisco Torreira University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1. Introduction In a large number of Spanish dialects, representing many of the world’s Spanish speakers, /s/ is reduced to or deleted entirely in word-internal preconsonantal position (e.g. /este/ → [ehte], este ‘this’), in word-final preconsonantal position (e.g. /las#toman/ → [lahtoman], las toman ‘they take them’), and/or in prepausal position (e.g. /komemos/ → [komemo(h)], comemos ‘we eat’). In those dialects considered the most phonologically innovative (such as the Spanish of Andalusia, Extremadura, Canary Islands, Hispanic Caribbean, Pacific coast of South America), /s/ debuccalization is also found in prevocalic environments word-finally (e.g. /las#alas/ → [lahala], las alas ‘the wings’) and even word-internally, this phenomenon being less common (e.g. /asi/ → [ahi], así ‘this way’). When considered in detail, the manifestations of aspirated-s can be very different depending on dialectal, phonetic and even sociolinguistic factors. Only in preconsonantal position, for example, different s-apirating dialects behave differently; and, even within each dialect and in preconsonantal position, different manifestations arise as a result of the consonant type following aspirated-s. In this study, I show that aspirated-s before voiceless stops has different phonetic characteristics in Western Andalusian, on one part, and Puerto Rican and Porteño Spanish on the other. While Western Andalusian exhibits consistent postaspiration and shorter or inexistent preaspiration, Puerto Rican and Porteño display consistent preaspiration but no postaspiration. Moreover, Andalusian Spanish voiceless stops in /hC/ clusters show a longer closure than voiceless stops in other conditions, a contrast that does not apply for Porteño and Puerto Rican Spanish. -

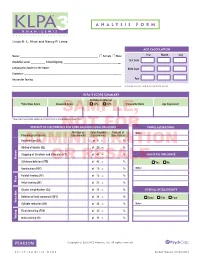

Sample, Not for Administration Or Resale

ANALYSIS FORM Linda M. L. Khan and Nancy P. Lewis Age Calculation Name: ______________________________________________________ u Female u Male Year Month Day Test Date Grade/Ed. Level: __________ School/Agency: __________________________________________ Language(s) Spoken in the Home: ___________________________________________________ Birth Date Examiner: ____________________________________________________________________ Reason for Testing: ______________________________________________________________ Age ____________________________________________________________________________ Reminder: Do not round up to next month or year. KLPA–3 Score Summary Confidence Interval *Total Raw Score Standard Score 90% 95% Percentile Rank Age Equivalent SAMPLE,– * Raw score equals total number of occurrences of scored phonological processes. Percent of OccurrenceNOT for Core Phonological ProcessesFOR Vowel Alterations Number of Total Possible Percent of Notes: Phonological Process Occurrences Occurrences Occurrences DeaffricationADMINISTRATION (DF) of 8 = % Gliding of liquids (GL) of 20 = % Stopping of fricatives and affricates (ST) of 48 = % Dialectal Influence Manner OR RESALE Stridency deletion (STR) of 42 = % Yes No Vocalization (VOC) of 15 = % Notes: Palatal fronting (PF) of 12 = % Place Velar fronting (VF) of 23 = % Cluster simplification (CS) of 23 = % Overall Intelligibility Deletion of final consonant (DFC) of 36 = % Good Fair Poor Reduction Syllable reduction (SR) of 25 = % Notes: Final devoicing (FDV) of 35 = % Voicing Initial voicing -

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin Essay Title: The sound system of Japanese This essay aims to introduce the sound system of Japanese, including the inventories of consonants, vowels, and diphthongs. The phonological variations of the sound segments in different phonetic environments are also included. For the illustration, word examples are given and they are presented in the following format: [IPA] (Romaji: “meaning”). Consonants In Japanese, there are 14 core consonants, and some of them have a lot of allophonic variations. The various types of consonants classified with respect to their manner of articulation are presented as follows. Stop Japanese has six oral stops or plosives, /p b t d k g/, which are classified into three place categories, bilabial, alveolar, and velar, as listed below. In each place category, there is a pair of plosives with the contrast in voicing. /p/ = a voiceless bilabial plosive [p]: [ippai] (ippai: “A cup of”) /b/ = a voiced bilabial plosive [b]: [baɴ] (ban: “Night”) /t/ = a voiceless alveolar plosive [t]: [oto̞ ːto̞ ] (ototo: “Brother”) /d/ = a voiced alveolar plosive [d]: [to̞ mo̞ datɕi] (tomodachi: “Friend”) /k/ = a voiceless velar plosive [k]: [kaiɰa] (kaiwa: “Conversation”) /g/ = a voiced velar plosive [g]: [ɡakɯβsai] (gakusai: “Student”) Phonetically, Japanese also has a glottal stop [ʔ] which is commonly produced to separate the neighboring vowels occurring in different syllables. This phonological phenomenon is known as ‘glottal stop insertion’. The glottal stop may be realized as a pause, which is used to indicate the beginning or the end of an utterance. For instance, the word “Japanese money” is actually pronounced as [ʔe̞ ɴ], instead of [je̞ ɴ], and the pronunciation of “¥15” is [dʑɯβːɡo̞ ʔe̞ ɴ]. -

Understanding the Tonada Cordobesa from an Acoustic

UNDERSTANDING THE TONADA CORDOBESA FROM AN ACOUSTIC, PERCEPTUAL AND SOCIOLINGUISTIC PERSPECTIVE by María Laura Lenardón B.A., TESOL, Universidad Nacional de Río Cuarto, 2000 M.A., Spanish Translation, Kent State University, 2003 M.A., Hispanic Linguistics, University of Pittsburgh, 2009 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2017 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by María Laura Lenardón It was defended on April 21, 2017 and approved by Dr. Shelome Gooden, Associate Professor of Linguistics, University of Pittsburgh Dr. Susana de los Heros, Professor of Hispanic Studies, University of Rhode Island Dr. Matthew Kanwit, Assistant Professor of Linguistics, University of Pittsburgh Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Scott F. Kiesling, Professor of Linguistics, University of Pittsburgh ii Copyright © by María Laura Lenardón 2017 iii UNDERSTANDING THE TONADA CORDOBESA FROM AN ACOUSTIC, PERCEPTUAL AND SOCIOLINGUISTIC PERSPECTIVE María Laura Lenardón, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2017 The goal of this dissertation is to gain a better understanding of a non-standard form of pretonic vowel lengthening or the tonada cordobesa, in Cordobese Spanish, an understudied dialect in Argentina. This phenomenon is analyzed in two different but complementary studies and perspectives, each of which contributes to a better understanding of the sociolinguistic factors that constrain its variation, as well as the social meanings of this feature in Argentina. Study 1 investigates whether position in the intonational phrase (IP), vowel concordance, and social class and gender condition pretonic vowel lengthening from informal conversations with native speakers (n=20). -

Vocale Incerta, Vocale Aperta*

Vocale Incerta, Vocale Aperta* Michael Kenstowicz Massachusetts Institute of Technology Omaggio a P-M. Bertinetto Ogni toscano si comporta di fronte a una parola a lui nuova, come si nota p. es. nella lettura del latino, scegliendo costantamente, e inconsciamente, il timbro aperto, secondo il principio che il Migliorini ha condensato nella formula «vocale incerta, vocale aperta»…è il processo a cui vien sottoposto ogni vocabolo importato o adattato da altri linguaggi. (Franceschi 1965:1-3) 1. Introduction Standard Italian distinguishes seven vowels in stressed nonfinal syllables. The open ɛ,ɔ vs. closed e,o mid-vowel contrast (transcribed here as open è,ò vs. closed é,ó) is neutralized in unstressed position (1). (1) 3 sg. infinitive tócca toccàre ‘touch’ blòcca bloccàre ‘block’ péla pelàre ‘pluck’ * A preliminary version of this paper was presented at the MIT Phonology Circle and the 40th Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages, University of Washington (March 2010). Thanks to two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments as well as to Maria Giavazzi, Giovanna Marotta, Joan Mascaró, Andrea Moro, and Mario Saltarelli. 1 gèla gelàre ‘freeze’ The literature uniformly identifies the unstressed vowels as closed. Consequently, the open è and ò have more restricted distribution and hence by traditional criteria would be identified as "marked" (Krämer 2009). In this paper we examine various lines of evidence indicating that the open vowels are optimal in stressed (open) syllables (the rafforzamento of Nespor 1993) and thus that the closed é and ó are "marked" in this position: {è,ò} > {é,ó} (where > means “better than” in the Optimality Theoretic sense). -

UC Berkeley Phonlab Annual Report

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley PhonLab Annual Report Title Strengthening, Weakening and Variability: The Articulatory Correlates of Hypo- and Hyper- articulation in the Production of English Dental Fricatives Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1hw2719n Journal UC Berkeley PhonLab Annual Report, 14(1) ISSN 2768-5047 Author Melguy, Yevgeniy Publication Date 2018 DOI 10.5070/P7141042482 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UC Berkeley Phonetics and Phonology Lab Annual Report (2018) Yevgeniy Melguy Susan Lin, Brian Smith M.A. Qualifying Paper 9 December 2018 Strengthening, weakening and variability: The articulatory correlates of hypo- and hyper- articulation in the production of English dental fricatives 1. INTRODUCTION A number of influential approaches to understanding phonetic and phonological variation in speech have highlighted the importance of functional factors (Blevins, 2004; Donegan & Stampe, 1979; Kiparsky, 1988; Kirchner, 1998; Lindblom, 1990). Under such approaches, speaker- and listener-oriented principles—ease of articulation vs. perceptual clarity—often work in opposite directions with respect to consonantal articulation. Minimization of effort is thought to drive a general “weakening” of consonants (resulting in decreased articulatory constriction and/or duration) which often makes them more articulatorily similar to surrounding sounds. This can result in assimilation, lenition, and ultimately deletion, and generally comes at the expense of clarity. By contrast, maximization of clarity drives consonantal “strengthening” processes (resulting in increased articulatory constriction and/or duration) that makes target segments more distinct from neighboring sounds, which can result in fortition. Clear speech generally involves more extreme or “forceful” articulations, and usually comes at the expense of requiring more articulatory effort from the speaker. -

Yo Puedo: Para Empezar

SUNY Geneseo KnightScholar Milne Open Textbooks Open Educational Resources 7-16-2021 Yo puedo: para empezar Elizabeth Silvaggio-Adams Rocío Vallejo-Alegre Follow this and additional works at: https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/oer-ost This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License Yo puedo para empezar Elizabeth Silvaggio-Adams & Ma. Del Rocío Vallejo-Alegre Milne Open Textbooks Geneseo, NY ISBN: 978-1-942341-83-3 © Elizabeth Silvaggio-Adams & Ma. Del Rocío Vallejo-Alegre Some Rights Reserved This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. We want to acknowledge the following websites for providing free access to openly licensed images that help illustrate and give life to our books to benefit our students: • WPClipart • Openclipart • Pixabay • Pixy.org • Pxhere.com • The LandView 6 and MARPLOT Milne Open Textbooks, One College Circle, Geneseo, NY Acknowledgements We thank the following people for their participation in providing materials and converting the Yo puedo series to the Open Educational Resources and systems support: + Allison Brown + Michelle Costello + Marie Shero + Eduardo Vallejo-Resines *************************************************************************** Be The Change The royalties from the print version of this book will be donated to Cultures Learning TOGETHER, Inc. Mission Cultures Learning TOGETHER is a win-win organization that enables people with different backgrounds and experiences to break linguistic barriers and embrace cultural diversity. Grounded in inclusion and belonging, we are a team of learners that exchange knowledge to unite our community with a network of cross-cultural bridges. Vision We aspire to create a permanent safe space to grow and connect the community through teaching, learning, and cultural integration. -

Wagner 1 Dutch Fricatives Dutch Is an Indo-European Language of The

Wagner 1 Dutch Fricatives Dutch is an Indo-European language of the West Germanic branch, closely related to Frisian and English. It is spoken by about 22 million people in the Netherlands, Belgium, Aruba, Suriname, and the Netherlands Antilles, nations in which the Dutch language also has an official status. Additionally, Dutch is still spoken in parts of Indonesia as a result of colonial rule, but it has been replaced by Afrikaans in South Africa. In the Netherlands, Algemeen Nederlands is the standard form of the language taught in schools and used by the government. It is generally spoken in the western part of the country, in the provinces of Nord and Zuid Holland. The Netherlands is divided into northern and southern regions by the Rijn river and these regions correspond to the areas where the main dialects of Dutch are distinguished from each other. My consultant, Annemarie Toebosch, is from the village of Bemmel in the Netherlands. Her dialect is called Betuws Dutch because Bemmel is located in the Betuwe region between two branches of the Rijn river. Toebosch lived in the Netherlands until the age of 25 when she relocated to the United States for graduate school. Today she is a professor of linguistics at the University of Michigan-Flint and speaks only English in her professional career. For the past 18 months she has been speaking Dutch more at home with her son, but in the 9 years prior to that, she only spoke Dutch once or twice a week with her parents and other relatives who remain in the Netherlands.