Theoretical and Typological Issues in Consonant Harmony by Gunnar Ólafur Hansson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Consonant Harmony in Child Language

1 Consonant Harmony in Child Language: An Optimality-theoretic Account* Heather Goad Department of Linguistics, McGill University [email protected] Ms. dated 1995. Currently in press in S.J. Hannahs & M. Young-Scholten Focus on phonological acquisition. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 113-142. Abstract An analysis is provided of the consonant harmony (CH) patterns exhibited in the speech of one child, Amahl at Stage 1 (data from Smith 1973). It is argued that the standard rule-based analysis which involves Coronal underspecification and planar segregation is not tenable. First, the data reveal an underspecification paradox: coronal consonants are targets for CH and should thus be unspecified for Coronal. However, they also trigger harmony, in words where the targets are liquids. Second, the data are not consistent with planar segregation, as one harmony pattern is productive beyond the point when AmahlÕs grammar satisfies the requirements for planar segregation (set forth in McCarthy 1989). An alternative analysis is proposed within the constraint-based framework of Optimality Theory (Prince & Smolensky 1993). It is argued that CH follows from the relative ranking of constraints which parse place features and those which align features with the edges of the prosodic word. With the constraints responsible for parsing and aligning Labial and Dorsal ranked above those responsible for parsing and aligning Coronal, the dual behaviour of coronals can be captured. The effect of planar segregation follows from other independently motivated constraints which force alignment to be satisfied through copying of segmental material, not through spreading. Keywords: first language acquisition, consonant harmony, underspecification paradox 1. -

Repercussions of the History of a Typological Change in Germanic

Repercussions of the history of a typological change in Germanic. Roland Noske Université Lille 3 / CNRS UMR 8163 [email protected] Abstract. In acoustic experimental phonetic investigations, the distinction made by Pike (1945) and Abercrombie (1967) between syllable-timed and stress timed has been refuted on several occasions. (e.g. by Wenk and Wioland 1982). However, perceptual research (Dauer 1983, 1987) has given rise to re-instalment of this typology by Auer (1993, 2001). Auer proposes a gradual, multi-factorial typology between syllable counting languages (also called simply syllable languages) and stress counting languages (or word languages). In this typology, several indicators are used for positioning a language on the continuous scale between the syllable language prototype and the word language prototype. These indicators include, among others, complexity of syllable structure, the occurrence of geminate clusters, tonality, tonal phenomena, the occurrence of vowel harmony or metaphony, epenthesis, vowel deletion, liaison, the occurrence of internal and external sandhi, as well as morphological reanalyses. In this paper, this typology will be used to show that in the course of time, most West- Germanic dialects have moved gradually from the syllable type to the word type. Evidence for this comes from research done on Old High German and Midlle High German texts, as well as from German dialectology. It will be shown that the contrast between Northern an Southern Dutch with respect to liaison across word boundaries and the vowel deletion promoting regular syllable structure (both indicators for syllable language-hood), is not the result of a French influence (as assumed by Noske (2005, 2006, 2007). -

The Phonetics-Phonology Interface in Romance Languages José Ignacio Hualde, Ioana Chitoran

Surface sound and underlying structure : The phonetics-phonology interface in Romance languages José Ignacio Hualde, Ioana Chitoran To cite this version: José Ignacio Hualde, Ioana Chitoran. Surface sound and underlying structure : The phonetics- phonology interface in Romance languages. S. Fischer and C. Gabriel. Manual of grammatical interfaces in Romance, 10, Mouton de Gruyter, pp.23-40, 2016, Manuals of Romance Linguistics, 978-3-11-031186-0. hal-01226122 HAL Id: hal-01226122 https://hal-univ-paris.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01226122 Submitted on 24 Dec 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Manual of Grammatical Interfaces in Romance MRL 10 Brought to you by | Université de Paris Mathematiques-Recherche Authenticated | [email protected] Download Date | 11/1/16 3:56 PM Manuals of Romance Linguistics Manuels de linguistique romane Manuali di linguistica romanza Manuales de lingüística románica Edited by Günter Holtus and Fernando Sánchez Miret Volume 10 Brought to you by | Université de Paris Mathematiques-Recherche Authenticated | [email protected] Download Date | 11/1/16 3:56 PM Manual of Grammatical Interfaces in Romance Edited by Susann Fischer and Christoph Gabriel Brought to you by | Université de Paris Mathematiques-Recherche Authenticated | [email protected] Download Date | 11/1/16 3:56 PM ISBN 978-3-11-031178-5 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-031186-0 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-039483-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. -

5 Phonology Florian Lionnet and Larry M

5 Phonology Florian Lionnet and Larry M. Hyman 5.1. Introduction The historical relation between African and general phonology has been a mutu- ally beneficial one: the languages of the African continent provide some of the most interesting and, at times, unusual phonological phenomena, which have con- tributed to the development of phonology in quite central ways. This has been made possible by the careful descriptive work that has been done on African lan- guages, by linguists and non-linguists, and by Africanists and non-Africanists who have peeked in from time to time. Except for the click consonants of the Khoisan languages (which spill over onto some neighboring Bantu languages that have “borrowed” them), the phonological phenomena found in African languages are usually duplicated elsewhere on the globe, though not always in as concen- trated a fashion. The vast majority of African languages are tonal, and many also have vowel harmony (especially vowel height harmony and advanced tongue root [ATR] harmony). Not surprisingly, then, African languages have figured dispro- portionately in theoretical treatments of these two phenomena. On the other hand, if there is a phonological property where African languages are underrepresented, it would have to be stress systems – which rarely, if ever, achieve the complexity found in other (mostly non-tonal) languages. However, it should be noted that the languages of Africa have contributed significantly to virtually every other aspect of general phonology, and that the various developments of phonological theory have in turn often greatly contributed to a better understanding of the phonologies of African languages. Given the considerable diversity of the properties found in different parts of the continent, as well as in different genetic groups or areas, it will not be possible to provide a complete account of the phonological phenomena typically found in African languages, overviews of which are available in such works as Creissels (1994) and Clements (2000). -

UC Berkeley Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society

UC Berkeley Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society Title Perception of Illegal Contrasts: Japanese Adaptations of Korean Coda Obstruents Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6x34v499 Journal Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, 36(36) ISSN 2377-1666 Author Whang, James D. Y. Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California PROCEEDINGS OF THE THIRTY SIXTH ANNUAL MEETING OF THE BERKELEY LINGUISTICS SOCIETY February 6-7, 2010 General Session Special Session Language Isolates and Orphans Parasession Writing Systems and Orthography Editors Nicholas Rolle Jeremy Steffman John Sylak-Glassman Berkeley Linguistics Society Berkeley, CA, USA Berkeley Linguistics Society University of California, Berkeley Department of Linguistics 1203 Dwinelle Hall Berkeley, CA 94720-2650 USA All papers copyright c 2016 by the Berkeley Linguistics Society, Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN: 0363-2946 LCCN: 76-640143 Contents Acknowledgments v Foreword vii Basque Genitive Case and Multiple Checking Xabier Artiagoitia . 1 Language Isolates and Their History, or, What's Weird, Anyway? Lyle Campbell . 16 Putting and Taking Events in Mandarin Chinese Jidong Chen . 32 Orthography Shapes Semantic and Phonological Activation in Reading Hui-Wen Cheng and Catherine L. Caldwell-Harris . 46 Writing in the World and Linguistics Peter T. Daniels . 61 When is Orthography Not Just Orthography? The Case of the Novgorod Birchbark Letters Andrew Dombrowski . 91 Gesture-to-Speech Mismatch in the Construction of Problem Solving Insight J.T.E. Elms . 101 Semantically-Oriented Vowel Reduction in an Amazonian Language Caleb Everett . 116 Universals in the Visual-Kinesthetic Modality: Politeness Marking Features in Japanese Sign Language (JSL) Johnny George . -

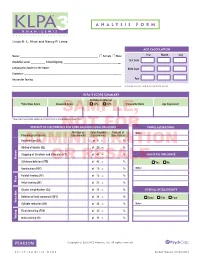

Sample, Not for Administration Or Resale

ANALYSIS FORM Linda M. L. Khan and Nancy P. Lewis Age Calculation Name: ______________________________________________________ u Female u Male Year Month Day Test Date Grade/Ed. Level: __________ School/Agency: __________________________________________ Language(s) Spoken in the Home: ___________________________________________________ Birth Date Examiner: ____________________________________________________________________ Reason for Testing: ______________________________________________________________ Age ____________________________________________________________________________ Reminder: Do not round up to next month or year. KLPA–3 Score Summary Confidence Interval *Total Raw Score Standard Score 90% 95% Percentile Rank Age Equivalent SAMPLE,– * Raw score equals total number of occurrences of scored phonological processes. Percent of OccurrenceNOT for Core Phonological ProcessesFOR Vowel Alterations Number of Total Possible Percent of Notes: Phonological Process Occurrences Occurrences Occurrences DeaffricationADMINISTRATION (DF) of 8 = % Gliding of liquids (GL) of 20 = % Stopping of fricatives and affricates (ST) of 48 = % Dialectal Influence Manner OR RESALE Stridency deletion (STR) of 42 = % Yes No Vocalization (VOC) of 15 = % Notes: Palatal fronting (PF) of 12 = % Place Velar fronting (VF) of 23 = % Cluster simplification (CS) of 23 = % Overall Intelligibility Deletion of final consonant (DFC) of 36 = % Good Fair Poor Reduction Syllable reduction (SR) of 25 = % Notes: Final devoicing (FDV) of 35 = % Voicing Initial voicing -

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin Essay Title: The sound system of Japanese This essay aims to introduce the sound system of Japanese, including the inventories of consonants, vowels, and diphthongs. The phonological variations of the sound segments in different phonetic environments are also included. For the illustration, word examples are given and they are presented in the following format: [IPA] (Romaji: “meaning”). Consonants In Japanese, there are 14 core consonants, and some of them have a lot of allophonic variations. The various types of consonants classified with respect to their manner of articulation are presented as follows. Stop Japanese has six oral stops or plosives, /p b t d k g/, which are classified into three place categories, bilabial, alveolar, and velar, as listed below. In each place category, there is a pair of plosives with the contrast in voicing. /p/ = a voiceless bilabial plosive [p]: [ippai] (ippai: “A cup of”) /b/ = a voiced bilabial plosive [b]: [baɴ] (ban: “Night”) /t/ = a voiceless alveolar plosive [t]: [oto̞ ːto̞ ] (ototo: “Brother”) /d/ = a voiced alveolar plosive [d]: [to̞ mo̞ datɕi] (tomodachi: “Friend”) /k/ = a voiceless velar plosive [k]: [kaiɰa] (kaiwa: “Conversation”) /g/ = a voiced velar plosive [g]: [ɡakɯβsai] (gakusai: “Student”) Phonetically, Japanese also has a glottal stop [ʔ] which is commonly produced to separate the neighboring vowels occurring in different syllables. This phonological phenomenon is known as ‘glottal stop insertion’. The glottal stop may be realized as a pause, which is used to indicate the beginning or the end of an utterance. For instance, the word “Japanese money” is actually pronounced as [ʔe̞ ɴ], instead of [je̞ ɴ], and the pronunciation of “¥15” is [dʑɯβːɡo̞ ʔe̞ ɴ]. -

Is Phonological Consonant Epenthesis Possible? a Series of Artificial Grammar Learning Experiments

Is Phonological Consonant Epenthesis Possible? A Series of Artificial Grammar Learning Experiments Rebecca L. Morley Abstract Consonant epenthesis is typically assumed to be part of the basic repertoire of phonological gram- mars. This implies that there exists some set of linguistic data that entails epenthesis as the best analy- sis. However, a series of artificial grammar learning experiments found no evidence that learners ever selected an epenthesis analysis. Instead, phonetic and morphological biases were revealed, along with individual variation in how learners generalized and regularized their input. These results, in combi- nation with previous work, suggest that synchronic consonant epenthesis may only emerge very rarely, from a gradual accumulation of changes over time. It is argued that the theoretical status of epenthesis must be reconsidered in light of these results, and that investigation of the sufficient learning conditions, and the diachronic developments necessary to produce those conditions, are of central importance to synchronic theory generally. 1 Introduction Epenthesis is defined as insertion of a segment that has no correspondent in the relevant lexical, or un- derlying, form. There are various types of epenthesis that can be defined in terms of either the insertion environment, the features of the epenthesized segment, or both. The focus of this paper is on consonant epenthesis and, more specifically, default consonant epenthesis that results in markedness reduction (e.g. Prince and Smolensky (1993/2004)). Consonant -

A Typology of Consonant Agreement As Correspondence

A TYPOLOGY OF CONSONANT AGREEMENT AS CORRESPONDENCE SHARON ROSE RACHEL WALKER University of California, San Diego University of Southern California This article presents a typology of consonant harmony or LONG DISTANCE CONSONANT AGREEMENT that is analyzed as arisingthroughcorrespondence relations between consonants rather than feature spreading. The model covers a range of agreement patterns (nasal, laryngeal, liquid, coronal, dorsal) and offers several advantages. Similarity of agreeing consonants is central to the typology and is incorporated directly into the constraints drivingcorrespondence. Agreementby correspon- dence without feature spreadingcaptures the neutrality of interveningsegments,which neither block nor undergo. Case studies of laryngeal agreement and nasal agreement are presented, demon- stratingthe model’s capacity to capture varyingdegreesof similarity crosslinguistically.* 1. INTRODUCTION. The action at a distance that is characteristic of CONSONANT HAR- MONIES stands as a pivotal problem to be addressed by phonological theory. Consider the nasal alternations in the Bantu language, Kikongo (Meinhof 1932, Dereau 1955, Webb 1965, Ao 1991, Odden 1994, Piggott 1996). In this language, the voiced stop in the suffix [-idi] in la is realized as [ini] in 1b when preceded by a nasal consonant at any distance in the stem constituent, consistingof root and suffixes. (1) a. m-[bud-idi]stem ‘I hit’ b. tu-[kun-ini]stem ‘we planted’ n-[suk-idi]stem ‘I washed’ tu-[nik-ini]stem ‘we ground’ In addition to the alternation in 1, there are no Kikongo roots containing a nasal followed by a voiced stop, confirmingthat nasal harmony or AGREEMENT, as we term it, also holds at the root level as a MORPHEME STRUCTURE CONSTRAINT (MSC). -

Final Pre-Print. Version 7.0

Final pre-print. Version 7.0. German, and conversely for /ts/, but seventy years after Trubetzkoy (1939) dis- cussed it, there is still no unanimity among phonologists. Phonologists studying Clicks, Concurrency, and Khoisan German range from those who admit no affricates at all, to those admit every phonetic affricate as a phonological affricate – see Wiese (2000) for a brief re- view. This article, on the other hand, is concerned with the word LINEAR, which is Julian Bradfield part of the usual understanding of SEGMENT. I claim that the restriction to lin- earity is an undue restriction on the definitions of segment (and hence phoneme), University of Edinburgh and that in some languages, entities traditionally viewed as single segments should be viewed as clusters. The difference is that the clusters are concurrent, rather than sequential. To put the thesis in a sentence, sometimes a co-articulated Abstract: I propose that the notions of segment and phoneme be en- segment really is better seen as two articulated co-segments. riched to allow, even in classical theories, some concurrent clustering. The notion of concurrent units is already commonplace in certain situations; My main application is the Khoisan language !Xóõ, where by treating clicks as phonemes concurrent with phonemic accompaniments, the in- languages with lexical tone are viewed as placing tones atop segmental units, ventory size is radically reduced, so solving the problems of many un- whether vowels, syllables or words, and sign languages often compose articu- supported contrasts. I show also how phonological processes of !Xóõ lations from each hand – though there one can argue about whether the com- can be described more elegantly in this setting, and provide support position belongs in the ‘phonology’. -

The Sound Patterns of Camuno: Description and Explanation in Evolutionary Phonology

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2014 The Sound Patterns Of Camuno: Description And Explanation In Evolutionary Phonology Michela Cresci Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/191 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE SOUND PATTERNS OF CAMUNO: DESCRIPTION AND EXPLANATION IN EVOLUTIONARY PHONOLOGY by MICHELA CRESCI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City Universtiy of New York 2014 i 2014 MICHELA CRESCI All rights reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Linguistics in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. JULIETTE BLEVINS ____________________ __________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee GITA MARTOHARDJONO ____________________ ___________________________________ Date Executive Officer KATHLEEN CURRIE HALL DOUGLAS H. WHALEN GIOVANNI BONFADINI Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract THE SOUND PATTERNS OF CAMUNO: DESCRIPTION AND EXPLANATION IN EVOLUTIONARY PHONOLOGY By Michela Cresci Advisor: Professor Juliette Blevins This dissertation presents a linguistic study of the sound patterns of Camuno framed within Evolutionary Phonology (Blevins, 2004, 2006, to appear). Camuno is a variety of Eastern Lombard, a Romance language of northern Italy, spoken in Valcamonica. Camuno is not a local variety of Italian, but a sister of Italian, a local divergent development of the Latin originally spoken in Italy (Maiden & Perry, 1997, p. -

The Primary Laryngeal in Uralic and Beyond

JUHA JANHUNEN THE PRIMARY LARYNGEAL IN URALIC AND BEYOND 1. Laryngeals in synchronic systems Many languages, though not all, have in their phonemic inventory one or more segments that may be classifi ed as “laryngeals”, that is, as segments belonging to what may be called the “laryngeal range” of the consonantal paradigm. In a narrow sense of the term, the laryngeal range would comprise of only seg- ments produced with a laryngeal (glottal) primary articulation, but in a broad understanding this may be conveniently defi ned as comprising of any velar or postvelar consonants that are distinct from the basic velar stops [k ɡ] in terms of either the place or manner of articulation. Most laryngeals are continuants produced as either fricatives (with a relatively strong frication) or spirants (with a relatively weak frication) in the velar, uvular, pharyngeal, epiglottal or glottal zones of the vocal tract (cf. e.g. Ladefoged & Maddieson 1996: 39–46), though there are also non-continuant laryngeals produced as stops or affricates in the uvular and glottal zones. With the exception of the glottal stop [ʔ], which is pro- duced with a closure of the vocal chords, the segments classifi able as laryngeals can be either voiced or voiceless. It is synchronically typical of laryngeals that they often involve a consider- able lability of the articulatory parameters. Most languages have a very limited set of segments classifi able as laryngeals, which is why features such as place of articulation and voice are rarely fully exploited to distinguish one laryngeal from another. Many languages have only one segment in the laryngeal range, in which case its phonetic value can vary within a broad range.