N/:/R/ Correspondences in Albanian Dialects: Understanding the N>R Sound Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T3 Sandhi Rules of Different Prosodic Hierarchies

T3 Sandhi rules of different prosodic hierarchies Abstract This study conducts acoustic analysis on T3 sandhi of two characters across different boundaries of prosodic hierarchies. The experimental data partly support Chen (2000)’s view about sandhi domain that “T3 sandhi takes place obligatorily within MRU”, and “sandhi rule can not apply cross intonation phrase boundary”. Nonetheless, the results do not support his claim that “there are no intermediate sandhi hierarchies between MRU and intonation phrase”. On the contrary, it is found that, although T3 sandhi could occur across all kinds of hierarchical boundaries between MRU and intonation phrase, T3 sandhi rules within a foot (prosodic word), or between foots without pause, or between pauses without intonation (phonology phrase) are very different in terms of acoustic properties. Furthermore, based on the facts that (1) T3 sandhi could occur cross boundary of pauses and (2) phrase-final sandhi could be significantly lengthening, it is argued that T3 sandhi is due to dissimilation of low tones, rather than duration reduction within MRU domain. It is also demonstrated that tone sandhi and prosodic hierarchies may not be equivalently evaluated in Chinese phonology. Prosodic hierarchies are determined by pause and lengthening, not by tone sandhi. Key words: tone sandhi; prosodic hierarchies; boundary; Mandarin Chinese 1 Introduction So-called T3 sandhi in mandarin Chinese has been widely discussed in Chinese Phonology. Mandarin Chinese has four tones: T1 (level 55), T2 (rising 35), T3 (low-rise 214), T4 (falling 51).Generally, when a T3 is followed by another T3, it turns into T2. The rule could be simply stated as: 214->35/ ___214. -

Long-Distance /R/-Dissimilation in American English

Long-Distance /r/-Dissimilation in American English Nancy Hall August 14, 2009 1 Introduction In many varieties of American English, it is possible to drop one /r/ from cer- tain words that contain two /r/s, such as su(r)prise, pa(r)ticular, gove(r)nor, and co(r)ner. This type of /r/-deletion is done by speakers who are basically ‘rhotic’; that is, who generally do not drop /r/ in any other position. It is a type of dissimi- lation, because it avoids the presence of multiple rhotics within a word.1 This paper has two goals. The first is to expand the description of American /r/-dissimilation by bringing together previously published examples of the process with new examples from an elicitation study and from corpora. This data set reveals new generalizations about the phonological environments that favor dissimilation. The second goal is to contribute to the long-running debate over why and how dissimilation happens, and particularly long-distance dissimilation. There is dis- pute over whether long-distance dissimilation is part of the grammar at all, and whether its functional grounding is a matter of articulatory constraints, processing constraints, or perception. Data from American /r/-dissimilation are especially im- portant for this debate, because the process is active, it is not restricted to only a few morphemes, and it occurs in a living language whose phonetics can be studied. Ar- guments in the literature are more often based on ancient diachronic dissimilation processes, or on processes that apply synchronically only in limited morphological contexts (and hence are likely fossilized remnants of once wider patterns). -

Prosody of Tone Sandhi in Vietnamese Reduplications

Prosody of Tone Sandhi in Vietnamese Reduplications Authors Thu Nguyen Linguistics program E.M.S.A.H. University of Queensland St Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia Email: [email protected] John Ingram Linguistics program E.M.S.A.H. University of Queensland St Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia Email: [email protected] Abstract In this paper we take advantage of the segmental control afforded by full and partial Vietnamese reduplications on a constant carrier phrase to obtain acoustic evidence of assymetrical prominence relations (van der Hulst 2005), in support of a hypothesis that Vietnamese reduplications are phonetically right headed and that tone sandhi is a reduction phenomenon occurring on prosodically weak positions (Shih, 2005). Acoustic parameters of syllable duration (onset, nucleus and coda), F0 range, F0 contour, vowel intensity, spectral tilt and vowel formant structure are analyzed to determine: (1) which syllable of the two (base or reduplicant) is more prominent and (2) how the tone sandhi forms differ from their full reduplicated counterparts. Comparisons of full and partial reduplicant syllables in tone sandhi forms provide additional support for this analysis. Key words: tone sandhi, prosody, stress, reduplication, Vietnamese, acoustic analysis ____________________________ We would like to thank our subjects for offering their voices for the analysis, Dr. Nguyen Hong Nguyen for statistical advice and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions. The Postdoctoral research fellowship granted to the first author by the University of Queensland is acknowledged. Prosody of tone sandhi in Vietnamese reduplications 2 1. Introduction Vietnamese is a contour tone language, which is strongly syllabic in its phonological organization and morphology. -

Albanian Language Identification in Text

5 BSHN(UT)23/2017 ALBANIAN LANGUAGE IDENTIFICATION IN TEXT DOCUMENTS *KLESTI HOXHA.1, ARTUR BAXHAKU.2 1University of Tirana, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Department of Informatics 2University of Tirana, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Department of Mathematics email: [email protected] Abstract In this work we investigate the accuracy of standard and state-of-the-art language identification methods in identifying Albanian in written text documents. A dataset consisting of news articles written in Albanian has been constructed for this purpose. We noticed a considerable decrease of accuracy when using test documents that miss the Albanian alphabet letters “Ë” and “Ç” and created a custom training corpus that solved this problem by achieving an accuracy of more than 99%. Based on our experiments, the most performing language identification methods for Albanian use a naïve Bayes classifier and n-gram based classification features. Keywords: Language identification, text classification, natural language processing, Albanian language. Përmbledhje Në këtë punim shqyrtohet saktësia e disa metodave standarde dhe bashkëkohore në identifikimin e gjuhës shqipe në dokumente tekstuale. Për këtë qëllim është ndërtuar një bashkësi të dhënash testuese e cila përmban artikuj lajmesh të shkruara në shqip. Për tekstet shqipe që nuk përmbajnë gërmat “Ë” dhe “Ç” u vu re një zbritje e konsiderueshme e saktësisë së identifikimit të gjuhës. Për këtë arsye u krijua një korpus trajnues i posaçëm që e zgjidhi këtë problem duke arritur një saktësi prej më shumë se 99%. Bazuar në eksperimentet e kryera, metodat më të sakta për identifikimin e gjuhës shqipe përdorin një klasifikues “naive Bayes” dhe veçori klasifikuese të bazuara në n-grame. -

The Festvox Indic Frontend for Grapheme-To-Phoneme Conversion

The Festvox Indic Frontend for Grapheme-to-Phoneme Conversion Alok Parlikar, Sunayana Sitaram, Andrew Wilkinson and Alan W Black Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, USA aup, ssitaram, aewilkin, [email protected] Abstract Text-to-Speech (TTS) systems convert text into phonetic pronunciations which are then processed by Acoustic Models. TTS frontends typically include text processing, lexical lookup and Grapheme-to-Phoneme (g2p) conversion stages. This paper describes the design and implementation of the Indic frontend, which provides explicit support for many major Indian languages, along with a unified framework with easy extensibility for other Indian languages. The Indic frontend handles many phenomena common to Indian languages such as schwa deletion, contextual nasalization, and voicing. It also handles multi-script synthesis between various Indian-language scripts and English. We describe experiments comparing the quality of TTS systems built using the Indic frontend to grapheme-based systems. While this frontend was designed keeping TTS in mind, it can also be used as a general g2p system for Automatic Speech Recognition. Keywords: speech synthesis, Indian language resources, pronunciation 1. Introduction in models of the spectrum and the prosody. Another prob- lem with this approach is that since each grapheme maps Intelligible and natural-sounding Text-to-Speech to a single “phoneme” in all contexts, this technique does (TTS) systems exist for a number of languages of the world not work well in the case of languages that have pronun- today. However, for low-resource, high-population lan- ciation ambiguities. We refer to this technique as “Raw guages, such as languages of the Indian subcontinent, there Graphemes.” are very few high-quality TTS systems available. -

Phonetics and Phonology in Russian Unstressed Vowel Reduction: a Study in Hyperarticulation

Phonetics and Phonology in Russian Unstressed Vowel Reduction: A Study in Hyperarticulation Jonathan Barnes Boston University (Short title: Hyperarticulating Russian Unstressed Vowels) Jonathan Barnes Department of Modern Foreign Languages and Literatures Boston University 621 Commonwealth Avenue, Room 119 Boston, MA 02215 Tel: (617) 353-6222 Fax: (617) 353-4641 [email protected] Abstract: Unstressed vowel reduction figures centrally in recent literature on the phonetics-phonology interface, in part owing to the possibility of a causal relationship between a phonetic process, duration-dependent undershoot, and the phonological neutralizations observed in systems of unstressed vocalism. Of particular interest in this light has been Russian, traditionally described as exhibiting two distinct phonological reduction patterns, differing both in degree and distribution. This study uses hyperarticulation to investigate the relationship between phonetic duration and reduction in Russian, concluding that these two reduction patterns differ not in degree, but in the level of representation at which they apply. These results are shown to have important consequences not just for theories of vowel reduction, but for other problems in the phonetics-phonology interface as well, incomplete neutralization in particular. Introduction Unstressed vowel reduction has been a subject of intense interest in recent debate concerning the nature of the phonetics-phonology interface. This is the case at least in part due to the existence of two seemingly analogous processes bearing this name, one typically called phonetic, and the other phonological. Phonological unstressed vowel reduction is a phenomenon whereby a given language's full vowel inventory can be realized only in lexically stressed syllables, while in unstressed syllables some number of neutralizations of contrast take place, with the result that only a subset of the inventory is realized on the surface. -

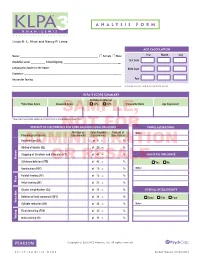

Sample, Not for Administration Or Resale

ANALYSIS FORM Linda M. L. Khan and Nancy P. Lewis Age Calculation Name: ______________________________________________________ u Female u Male Year Month Day Test Date Grade/Ed. Level: __________ School/Agency: __________________________________________ Language(s) Spoken in the Home: ___________________________________________________ Birth Date Examiner: ____________________________________________________________________ Reason for Testing: ______________________________________________________________ Age ____________________________________________________________________________ Reminder: Do not round up to next month or year. KLPA–3 Score Summary Confidence Interval *Total Raw Score Standard Score 90% 95% Percentile Rank Age Equivalent SAMPLE,– * Raw score equals total number of occurrences of scored phonological processes. Percent of OccurrenceNOT for Core Phonological ProcessesFOR Vowel Alterations Number of Total Possible Percent of Notes: Phonological Process Occurrences Occurrences Occurrences DeaffricationADMINISTRATION (DF) of 8 = % Gliding of liquids (GL) of 20 = % Stopping of fricatives and affricates (ST) of 48 = % Dialectal Influence Manner OR RESALE Stridency deletion (STR) of 42 = % Yes No Vocalization (VOC) of 15 = % Notes: Palatal fronting (PF) of 12 = % Place Velar fronting (VF) of 23 = % Cluster simplification (CS) of 23 = % Overall Intelligibility Deletion of final consonant (DFC) of 36 = % Good Fair Poor Reduction Syllable reduction (SR) of 25 = % Notes: Final devoicing (FDV) of 35 = % Voicing Initial voicing -

The Albanian Case in Italy

Palaver Palaver 9 (2020), n. 1, 221-250 e-ISSN 2280-4250 DOI 10.1285/i22804250v9i1p221 http://siba-ese.unisalento.it, © 2020 Università del Salento Majlinda Bregasi Università “Hasan Prishtina”, Pristina The socioeconomic role in linguistic and cultural identity preservation – the Albanian case in Italy Abstract In this article, author explores the impact of ever changing social and economic environment in the preservation of cultural and linguistic identity, with a focus on Albanian community in Italy. Comparisons between first major migration of Albanians to Italy in the XV century and most recent ones in the XX, are drawn, with a detailed study on the use and preservation of native language as main identity trait. This comparison presented a unique case study as the descendants of Arbëresh (first Albanian major migration) came in close contact, in a very specific set of circumstances, with modern Albanians. Conclusions in this article are substantiated by the survey of 85 immigrant families throughout Italy. The Albanian language is considered one of the fundamental elements of Albanian identity. It was the foundation for the rise of the national awareness process during Renaissance. But the situation of Albanian language nowadays in Italy among the second-generation immigrants shows us a fragile identity. Keywords: Language identity; national identity; immigrants; Albanian language; assimilation. 221 Majlinda Bregasi 1. An historical glance There are two basic dialect forms of Albanian, Gheg (which is spoken in most of Albania north of the Shkumbin river, as well as in Montenegro, Kosovo, Serbia, and Macedonia), and Tosk, (which is spoken on the south of the Shkumbin river and into Greece, as well as in traditional Albanian diaspora settlements in Italy, Bulgaria, Greece and Ukraine). -

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin Essay Title: The sound system of Japanese This essay aims to introduce the sound system of Japanese, including the inventories of consonants, vowels, and diphthongs. The phonological variations of the sound segments in different phonetic environments are also included. For the illustration, word examples are given and they are presented in the following format: [IPA] (Romaji: “meaning”). Consonants In Japanese, there are 14 core consonants, and some of them have a lot of allophonic variations. The various types of consonants classified with respect to their manner of articulation are presented as follows. Stop Japanese has six oral stops or plosives, /p b t d k g/, which are classified into three place categories, bilabial, alveolar, and velar, as listed below. In each place category, there is a pair of plosives with the contrast in voicing. /p/ = a voiceless bilabial plosive [p]: [ippai] (ippai: “A cup of”) /b/ = a voiced bilabial plosive [b]: [baɴ] (ban: “Night”) /t/ = a voiceless alveolar plosive [t]: [oto̞ ːto̞ ] (ototo: “Brother”) /d/ = a voiced alveolar plosive [d]: [to̞ mo̞ datɕi] (tomodachi: “Friend”) /k/ = a voiceless velar plosive [k]: [kaiɰa] (kaiwa: “Conversation”) /g/ = a voiced velar plosive [g]: [ɡakɯβsai] (gakusai: “Student”) Phonetically, Japanese also has a glottal stop [ʔ] which is commonly produced to separate the neighboring vowels occurring in different syllables. This phonological phenomenon is known as ‘glottal stop insertion’. The glottal stop may be realized as a pause, which is used to indicate the beginning or the end of an utterance. For instance, the word “Japanese money” is actually pronounced as [ʔe̞ ɴ], instead of [je̞ ɴ], and the pronunciation of “¥15” is [dʑɯβːɡo̞ ʔe̞ ɴ]. -

Europaio: a Brief Grammar of the European Language Reconstruct Than the Individual Groupings

1. Introduction 1.1. The Indo-European 1. The Indo-European languages are a family of several hundred languages and dialects, including most of the major languages of Europe, as well as many in South Asia. Contemporary languages in this family include English, German, French, Spanish, Countries with IE languages majority in orange. In Portuguese, Hindustani (i.e., mainly yellow, countries in which have official status. [© gfdl] Hindi and Urdu) and Russian. It is the largest family of languages in the world today, being spoken by approximately half the world's population as their mother tongue, while most of the other half speak at least one of them. 2. The classification of modern IE dialects into languages and dialects is controversial, as it depends on many factors, such as the pure linguistic ones (most of the times being the least important of them), the social, economic, political and historical ones. However, there are certain common ancestors, some of them old, well-attested languages (or language systems), as Classic Latin for Romance languages (such as French, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Rumanian or Catalan), Classic Sanskrit for the Indo-Aryan languages or Classic Greek for present-day Greek. Furthermore, there are other, still older -some of them well known- dialects from which these old language systems were derived and later systematized, which are, following the above examples, Archaic Latin, Archaic Sanskrit and Archaic Greek, also attested in older compositions and inscriptions. And there are, finally, old related dialects which help develop a Proto-Language, as the Faliscan (and Osco-Umbrian for many scholars) for Latino-Faliscan (Italic for many), the Avestan for Indo-Iranian or the Mycenaean for Proto-Greek. -

Illyrian-Albanian Continuity on the Areal of Kosova 29 Illyrian-Albanian Continuity on the Areal of Kosova

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by AAB College repository Illyrian-Albanian Continuity on the Areal of Kosova 29 Illyrian-Albanian Continuity on the Areal of Kosova Jahja Drançolli* Abstract In the present study it is examined the issue of Illyrian- Albanian continuity in the areal of Kosova, a scientific problem, which, due to the reasons of daily policy, has extremely become exploited (harnessed) until the present days. The politicisation of the ancient history of Kosova begins with the Eastern Crisis, a time when the programmes of Great-Serb aggression for the Balkans started being drafted. These programmes, inspired by the extra-scientific history dressed in myths, legends and folk songs, expressed the Serb aspirations to look for their cradle in Kosova, Vojvodina. Croatia, Dalmatia, Bosnia and Hercegovina and Montenegro. Such programmes, based on the instrumentalized history, have always been strongly supported by the political circles on the occasion of great historical changes, that have overwhelmed the Balkans. Key Words: Dardania and Dardans in antiquity, Arbers and Kosova during the Middle Ages, geopolitical, ethnic, religious and cultural concepts, which are known in the sources of that time followed by a chronological development. The region of Kosova preserves archeological monuments from the beginnings of Neolith (6000-2600 B.C.). Since that time the first settlements were constructed, including Tjerrtorja (Prishtinë), Glladnica (Graçanicë), Rakoshi (Istog), Fafos and Lushta (Mitrovicë), Reshtan and Hisar (Suharekë), Runik (Skenderaj) etc. The region of Kosova has since the Bronze Age been inhabited by Dardan Illyrians; the territory of extension of this region was much larger than the present-day territory of Kosova. -

Song As the Memory of Language in the Arbëresh Community of Chieuti

MY HEART SINGS TO ME: Song as the Memory of Language in the Arbëresh Community of Chieuti Sara Jane Bell A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Curriculum in Folklore. Chapel Hill 2011 Approved by: Dr. Robert Cantwell (Chair) Dr. William Ferris Dr. Louise Meintjes Dr. Patricia Sawin ABSTRACT SARA JANE BELL: My Heart Sings to Me: Song as the Memory of Language in the Arbëresh Community of Chieuti (Under the Direction of Robert Cantwell, Chair; William Ferris; Louise Meintjes; and Patricia Sawin) For the people of Chieuti who grew up speaking the Albanian dialect that the inhabitants of their Arbëresh town in the Italian province of Puglia have spoken for more than five centuries, the rapid decline of their mother tongue is a loss that is sorely felt. Musicians and cultural activists labor to negotiate new strategies for maintaining connections to their unique heritage and impart their traditions to young people who are raised speaking Italian in an increasingly interconnected world. As they perform, they are able to act out collective narratives of longing and belonging, history, nostalgia, and sense of place. Using the traditional song “Rine Rine” as a point of departure, this thesis examines how songs transmit linguistic and cultural markers of Arbëresh identity and serve to illuminate Chieuti’s position as a community poised in the moment of language shift. ii For my grandfather, Vincenzo Antonio Belpulso and for the children of Chieuti, at home and abroad, who carry on.