Normal Acquisition of Consonant Clusters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vietnamese Accent

Vietnamese English Erik Singer Vietnamese is spoken by about 86 million people, which makes it the 17th largest language community in the world. It is part of the Austro-Asiatic language family, and is by far the most widely spoken of these languages. It has borrowed a large portion of its vocabulary from Chinese, thanks to an early period of Chinese domination, but it is otherwise linguistically unrelated. It is generally described as having three dialects: Hanoi in the North, Ho Chi Minh in the South, and Hue in the center. The three dialects are mostly mutually intelligible, though Hue is said to be difficult for speakers of the other two dialects to understand. The northern speech…is marked by sharpness, or choppiness, with greater attention to the precise distinction of tones. The southern speech, in addition to certain uniform differences from northern speech in the pronunciation of consonants, does not distinguish between the hoi and nga tones; and, it is felt by some to sound more laconic and musical. The speech of the Center, on the other hand, is often described as being heavy because of its emphasis on low tones.1 Vietnamese uses the Latin alphabet, with additional diacritics to indicate tones. Vietnam itself is the world’s 13th most populous country, and the 8th most populous in Asia. It became independent from Imperial China in 938 BCE. Since 2000, it has been one of the fastest-growing economies in the world. Oral Posture Oral or vocal tract posture is the characteristic pattern of muscular engagement and relaxation inherent to a given language or accent. -

Consonant Cluster Acquisition by L2 Thai Speakers

English Language Teaching; Vol. 10, No. 7; 2017 ISSN 1916-4742 E-ISSN 1916-4750 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Consonant Cluster Acquisition by L2 Thai Speakers Apichai Rungruang1 1 Faculty of Humanities, Naresuan University, Phitsanulok, Thailand Correspondence: Apichai Rungruang, Faculty of Humanities, Naresuan University, Phitsanulok, Thailand. E-mail: [email protected] Received: April 29, 2017 Accepted: June 10, 2017 Online Published: June 13, 2017 doi: 10.5539/elt.v10n7p216 URL: http://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v10n7p216 Abstract Attempts to account for consonant cluster acquisition are always made into two aspects. One is transfer of the first language (L1), and another is markedness effects on the developmental processes in second language acquisition. This study has continued these attempts by finding out how well Thai university students were able to perceive English onset and coda clusters when they were second year and fourth year students. This paper also aims to investigate Thai speakers’ opinions about their listening and speaking skills, and whether their course subjects enhanced their performance. To fulfil the first objective, a pretest and posttest were launched to measure how the 34 Thai participants were able to identify 40 onset and 120 coda clusters at different periods of time. The statistical findings show that even though their overall scores in the fourth year were higher than those in the second year, there was no statistically significant difference in both major types of clusters [t = -1.29; p value >0.05 in onsets; t = -0.28; p value >0.05 in codas]. The Thai participants performed slightly better in onset (84% / 86%) than in coda (70% / 71%). -

Phonological Processes

Phonological Processes Phonological processes are patterns of articulation that are developmentally appropriate in children learning to speak up until the ages listed below. PHONOLOGICAL PROCESS DESCRIPTION AGE ACQUIRED Initial Consonant Deletion Omitting first consonant (hat → at) Consonant Cluster Deletion Omitting both consonants of a consonant cluster (stop → op) 2 yrs. Reduplication Repeating syllables (water → wawa) Final Consonant Deletion Omitting a singleton consonant at the end of a word (nose → no) Unstressed Syllable Deletion Omitting a weak syllable (banana → nana) 3 yrs. Affrication Substituting an affricate for a nonaffricate (sheep → cheep) Stopping /f/ Substituting a stop for /f/ (fish → tish) Assimilation Changing a phoneme so it takes on a characteristic of another sound (bed → beb, yellow → lellow) 3 - 4 yrs. Velar Fronting Substituting a front sound for a back sound (cat → tat, gum → dum) Backing Substituting a back sound for a front sound (tap → cap) 4 - 5 yrs. Deaffrication Substituting an affricate with a continuant or stop (chip → sip) 4 yrs. Consonant Cluster Reduction (without /s/) Omitting one or more consonants in a sequence of consonants (grape → gape) Depalatalization of Final Singles Substituting a nonpalatal for a palatal sound at the end of a word (dish → dit) 4 - 6 yrs. Stopping of /s/ Substituting a stop sound for /s/ (sap → tap) 3 ½ - 5 yrs. Depalatalization of Initial Singles Substituting a nonpalatal for a palatal sound at the beginning of a word (shy → ty) Consonant Cluster Reduction (with /s/) Omitting one or more consonants in a sequence of consonants (step → tep) Alveolarization Substituting an alveolar for a nonalveolar sound (chew → too) 5 yrs. -

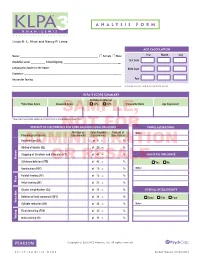

Sample, Not for Administration Or Resale

ANALYSIS FORM Linda M. L. Khan and Nancy P. Lewis Age Calculation Name: ______________________________________________________ u Female u Male Year Month Day Test Date Grade/Ed. Level: __________ School/Agency: __________________________________________ Language(s) Spoken in the Home: ___________________________________________________ Birth Date Examiner: ____________________________________________________________________ Reason for Testing: ______________________________________________________________ Age ____________________________________________________________________________ Reminder: Do not round up to next month or year. KLPA–3 Score Summary Confidence Interval *Total Raw Score Standard Score 90% 95% Percentile Rank Age Equivalent SAMPLE,– * Raw score equals total number of occurrences of scored phonological processes. Percent of OccurrenceNOT for Core Phonological ProcessesFOR Vowel Alterations Number of Total Possible Percent of Notes: Phonological Process Occurrences Occurrences Occurrences DeaffricationADMINISTRATION (DF) of 8 = % Gliding of liquids (GL) of 20 = % Stopping of fricatives and affricates (ST) of 48 = % Dialectal Influence Manner OR RESALE Stridency deletion (STR) of 42 = % Yes No Vocalization (VOC) of 15 = % Notes: Palatal fronting (PF) of 12 = % Place Velar fronting (VF) of 23 = % Cluster simplification (CS) of 23 = % Overall Intelligibility Deletion of final consonant (DFC) of 36 = % Good Fair Poor Reduction Syllable reduction (SR) of 25 = % Notes: Final devoicing (FDV) of 35 = % Voicing Initial voicing -

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin Essay Title: The sound system of Japanese This essay aims to introduce the sound system of Japanese, including the inventories of consonants, vowels, and diphthongs. The phonological variations of the sound segments in different phonetic environments are also included. For the illustration, word examples are given and they are presented in the following format: [IPA] (Romaji: “meaning”). Consonants In Japanese, there are 14 core consonants, and some of them have a lot of allophonic variations. The various types of consonants classified with respect to their manner of articulation are presented as follows. Stop Japanese has six oral stops or plosives, /p b t d k g/, which are classified into three place categories, bilabial, alveolar, and velar, as listed below. In each place category, there is a pair of plosives with the contrast in voicing. /p/ = a voiceless bilabial plosive [p]: [ippai] (ippai: “A cup of”) /b/ = a voiced bilabial plosive [b]: [baɴ] (ban: “Night”) /t/ = a voiceless alveolar plosive [t]: [oto̞ ːto̞ ] (ototo: “Brother”) /d/ = a voiced alveolar plosive [d]: [to̞ mo̞ datɕi] (tomodachi: “Friend”) /k/ = a voiceless velar plosive [k]: [kaiɰa] (kaiwa: “Conversation”) /g/ = a voiced velar plosive [g]: [ɡakɯβsai] (gakusai: “Student”) Phonetically, Japanese also has a glottal stop [ʔ] which is commonly produced to separate the neighboring vowels occurring in different syllables. This phonological phenomenon is known as ‘glottal stop insertion’. The glottal stop may be realized as a pause, which is used to indicate the beginning or the end of an utterance. For instance, the word “Japanese money” is actually pronounced as [ʔe̞ ɴ], instead of [je̞ ɴ], and the pronunciation of “¥15” is [dʑɯβːɡo̞ ʔe̞ ɴ]. -

On the Theoretical Implications of Cypriot Greek Initial Geminates

<LINK "mul-n*">"mul-r16">"mul-r8">"mul-r19">"mul-r14">"mul-r27">"mul-r7">"mul-r6">"mul-r17">"mul-r2">"mul-r9">"mul-r24"> <TARGET "mul" DOCINFO AUTHOR "Jennifer S. Muller"TITLE "On the theoretical implications of Cypriot Greek initial geminates"SUBJECT "JGL, Volume 3"KEYWORDS "geminates, representation, phonology, Cypriot Greek"SIZE HEIGHT "220"WIDTH "150"VOFFSET "4"> On the theoretical implications of Cypriot Greek initial geminates* Jennifer S. Muller The Ohio State University Cypriot Greek contrasts singleton and geminate consonants in word-initial position. These segments are of particular interest to phonologists since two divergent representational frameworks, moraic theory (Hayes 1989) and timing-based frameworks, including CV or X-slot theory (Clements and Keyser 1983, Levin 1985), account for the behavior of initial geminates in substantially different ways. The investigation of geminates in Cypriot Greek allows these differences to be explored. As will be demonstrated in a formal analysis of the facts, the patterning of geminates in Cypriot is best accounted for by assuming that the segments are dominated by abstract timing units such as X- or C-slots, rather than by a unit of prosodic weight such as the mora. Keywords: geminates, representation, phonology, Cypriot Greek 1. Introduction Cypriot Greek is of particular interest, not only because it is one of the few varieties of Modern Greek maintaining a consonant length contrast, but more importantly because it exhibits this contrast in word-initial position: péfti ‘Thursday’ vs. ppéfti ‘he falls’.Although word-initial geminates are less common than their word-medial counterparts, they are attested in dozens of the world’s languages in addition to Cypriot Greek. -

Mechanisms of Vowel Epenthesis in Consonant Clusters: an EMA Study Seiya Funatsu, Masako Fujimoto

Mechanisms of vowel epenthesis in consonant clusters: an EMA study Seiya Funatsu, Masako Fujimoto To cite this version: Seiya Funatsu, Masako Fujimoto. Mechanisms of vowel epenthesis in consonant clusters: an EMA study. Acoustics 2012, Apr 2012, Nantes, France. hal-00810613 HAL Id: hal-00810613 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00810613 Submitted on 23 Apr 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Proceedings of the Acoustics 2012 Nantes Conference 23-27 April 2012, Nantes, France Mechanisms of vowel epenthesis in consonant clusters: an EMA study S. Funatsua and M. Fujimotob aPrefectural University of Hiroshima, 1-1-71 Ujinahigashi Minami-ku, 734-8558 Hiroshima, Japan bNational Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics, 10-2 Midori-machi, 190-8561 Tachikawa, Japan [email protected] 341 23-27 April 2012, Nantes, France Proceedings of the Acoustics 2012 Nantes Conference The mechanisms of vowel epenthesis in consonant clusters were investigated using an electromagnetic articulograph (EMA). The target languages were Japanese and German. Japanese does not allow consonant clusters, while German does. Two Japanese speakers and two German speakers participated in this experiment. For Japanese speakers, normalized tongue tip displacements from the first consonant to the second consonant in clusters (/bn/, /pn/) were significantly larger than those of German speakers (p<0.001). -

Technologies for the Study of Speech: Review and an Application

Themes in Science & Technology Education, 8(1), 17-32, 2015 Technologies for the study of speech: Review and an application Elena Babatsouli [email protected] Institute of Monolingual and Bilingual Speech, Crete, Greece Abstract. Technologies used for the study of speech are classified here into non-intrusive and intrusive. The paper informs on current non-intrusive technologies that are used for linguistic investigations of the speech signal, both phonological and phonetic. Providing a point of reference, the review covers existing technological advances in language research methodology for normal and disordered speech, cutting across boundaries of sub-fields: child vs. adult; first, second, or bilingual; standard or dialectal. The indispensability of such technologies for investigating linguistic aspects of speech is evident in an application that uses CLAN to manage and perform phonological and computational analysis of a bilingual child’s dense speech data, longitudinally over 17 months of phonological development in Greek/English. Backed by acoustic analysis using Praat, developmental results on the child’s labio-velar approximant in English are also given. Keywords: technologies, normal/disordered speech, child development, CLAN Introduction Speech data feed the observation, documentation and analysis of oral language; theoretical speculations in phonology are grounded on phonetic evidence which, in turn, provide yardsticks for comparing the production of speech cross-linguistically in all its likely forms: child and adult; standard or dialectal; first (L1), second (L2), bilingual (L1ˡ2); normal or disordered. Despite the presence of universal patterns (Jakobson, 1941/1968) in speech, production variability is a prevalent phenomenon, sometimes going unnoticed and at other times drawing the listener’s attention to inaccuracy and even unintelligibility, as witnessed in random errors, idiolects, dialects, accents, speech disorders, and speech impairments. -

Samples of Phonological Development

Galasso Ling 417: Review Exam 1. A Synthesis: Representational Stages in Child Phonological and Morphological Development Lecture Review (Chapters 3-4) Galasso Stages of ‘Rule Representation’ Scheme: 1. Phonology 2. Morphology Pre-Representational Representational Pre-Representational Representational ·Idiomatic Speech ·Formulaic ·Partial rules ·Full rules ·Lexical ·Functional [prIti] /prIti/ ‘u-shape’: /bIdi/ Referential (‘pretty’) [CVCV] [CCVCV] | Context-bound Noun ↔ Determiner Phonological Rules: | Verb ↔ Auxiliary/Modal · Assimilation | | · Default voicing [car] ‘car’ | · Syllabic Development [raisins] [rainsins]-{es} (e.g., u-shape learning) [ø Pl] [+Pl] [Number] · weak syllable deletion | | [formulaic] ‘category’ [‘Iwant’] ‘I’ [Case] (p.169) word mapping/bootstrapping: Semantic Syntactic (p. 372) morphology processing: Derivational Inflectional teach-{er} teacher-{s} Data: (Galasso) ‘Sally Exp’ (Gordon) ‘Rat-eater Exp. fMRI Brain Imagining Overview: Children first produce language in a pre-representational way whereby both Phonology and Morphology are underdeveloped. Regarding phonology, idiomatic speech such as formulaic, echolalia and mimic expressions are the hallmark of a Pre-Representational stage, usually beginning as early as 14 months and lasting up until 24months (+/-20%). Regarding Morphology, chunking has been observed whereby young children (up until 24months) are seemingly unable to partition the morphological segments e.g., [stem+affix] and rather produce both as a single whole chunk—e.g., ‘raisins’ (as a singular word and where the plural {s}is not yet productive). 1 Galasso Ling 417: Review Exam 1. 1. Phonology: Phonemic/Syllabic Development and Consonant Harmony [1] The early production of the word ‘spaghetti’ offers linguists a valuable insight into the phonological rules children employ at the earliest stages of representational speech. (p. 93) (a) spaghetti → /bʌzgɛdi/ Above, spaghetti /sp∧gɛti/ becomes /b∧zgɛdi/ (CVC+CVCv) with initial /s/ deletion and strategic reinsertion (voiced to /z/) to create the /CVC-CVCv/ structure. -

Introduction: an Overview of Research on Prosodic Development

chapter 1 Introduction An overview of research on prosodic development Pilar Prieto1,2 & Núria Esteve-Gibert3,4 1Institució Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avançats (ICREA) / 2Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Department of Translation and Language Sciences / 3Aix Marseille Université, CNRS, LPL UMR 7309 / 4Universitat de Barcelona Prosody in spoken language, realized through patterns of timing, melody, and intensity, is used across languages to convey a wide range of language functions, which are crucial for both structuring information in speech and encoding an important set of semantico-pragmatic meanings. First and foremost, prosody con- stitutes the ‘organizational structure of speech’ (Beckman, 1996). We use it to sepa- rate our speech into chunks of information, thus helping our interlocutor to parse our discourse into meaningful syntactic units but also sending signals about when to take turns in our conversation. Secondly, prosody plays a key pragmatic role in conversation because it can convey a broad panoply of communicative meanings, ranging from the type of speech act (assertion, question, request, etc.), informa- tion status (given vs. new information, broad focus vs. narrow focus, contrast), belief status (or epistemic position of the speaker with respect to the information exchange), politeness, and affective states, to indexical functions such as gender, age, and the sociolectal and dialectal status of the speaker (Gussenhoven, 2004; Ladd, 2008; Nespor & Vogel, 2007; see Prieto, 2015, for a review). Finally, in many languages of the world, prosody can also encode phonological contrasts at the lexi- cal level through stress or tonal marking. These various organizational and semantico-pragmatic functions are mani- fested by means of prosodic phrasal grouping (via phrasal intonation markers), intonational prominence, and intonational modulations. -

Chapter 9 Consonant Substitution in Child Language (Ikwere) Roseline I

Chapter 9 Consonant substitution in child language (Ikwere) Roseline I. C. Alerechi University of Port Harcourt The Ikwere language is spoken in four out of the twenty-three Local Government Areas (LGAs) of Rivers State of Nigeria, namely, Port Harcourt, Obio/Akpor, Emohua and Ikwerre LGAs. Like Kana, Kalabari and Ekpeye, it is one of the major languages of Rivers State of Nigeria used in broadcasting in the electronic media. The Ikwere language is classified asan Igboid language of the West Benue-Congo family of the Niger-Congo phylum of languages (Williamson 1988: 67, 71, Williamson & Blench 2000: 31). This paper treats consonant substi- tution in the speech of the Ikwere child. It demonstrates that children use of a language can contribute to the divergent nature of that language as they always strive for simplification of the target language. Using simple descriptive method of data analysis, the paper identifies the various substitutions of consonant sounds, which characterize the Ikwere children’s ut- terances. It stresses that the substitutions are regular and rule governed and hence implies the operation of some phonological processes. Some of the processes are strengthening and weakening of consonants, loss of suction of labial implosives causing them to become labial plosives, devoicing of voiced consonants, etc. While some of these processes are identical with the adult language, others are peculiar to children, demonstrating the relationships between the phonological processes in both forms of speech. It is worthy of note that high- lighting the relationships and differences will make for effective communication between children and adults. 1 Introduction The Ikwere language is spoken in four out of the twenty-three Local Government Areas (LGAs) of Rivers State of Nigeria, namely, Port Harcourt, Obio/Akpor, Emohua and Ik- werre LGAs. -

Phonological Development of an Arabic-English Bilingual Child During the One-Word Stage

Linguistics and Literature Studies 5(5): 354-364, 2017 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/lls.2017.050504 Phonological Development of an Arabic-English Bilingual Child during the One-word Stage Hana A. Daana Princess Alia University College, Al-Balqa Applied University, Jordan Copyright©2017 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract The main purpose of this article is to provide a Daana [32] 2009; Salim and Mehawesh [33] 2014). None of description of the phonological development in the speech of these studies have dealt with the early phonological an Arabic-English bilingual child during the meaningful development during the meaningful first-word stage. In one-word production stage that is from 7 to 20 months of age. addition, none of them have traced the development of Data presented here are the result of recording sessions of English and Arabic sounds in the speech of a bilingual child. spontaneous and non-spontaneous speech between the child As far as the early phonological development in the speech and the author. The record, thus, is representative of the of a bilingual child is concerned, Keshavarz and Ingram [25] sounds which were produced in a meaningful verbal context. (2002) investigated the early development of the phonology To the author’s best knowledge, data on the phonological of Farsi and English in the speech of Keshavarz’ son development of an Arabic-English bilingual child has not applying the ‘opposition theory’ suggested by Jakobson [2] been published before.