Queer Tango Histories: Making a Start…

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mark Tompkins, Chez Qui La Voix Est Centrale

CN D P R I N - T E M P S 2 0 1 8 Centre national de la danse Réservations et informations pratiques + 33 (0)1 41 83 98 98 cnd.fr 1 2 JE NE REVIENS PAS, JE VIENS Pour peu que l’on ne s’allonge pas sous les images, chacune, chacun d’entre nous, du laboratoire à l’usine, du prétoire au spectacle vivant, du divan au concert, du cinéma à la consultation, du livre à l’autre, de l’école à la rue, pensons et agissons selon « je ne reviens pas, je viens » (Mahmoud Darwich). Pour en sortir essayons tout. Rassemblons audacieusement et courageusement. Il ne s’agit pas de se clore dans un assemblement mais de vivre ensemble conflictuellement sans doute avec des contradictions évolutives pour fabriquer les processus qui mèneront progressivement en arrachant le chiendent de l’ignorance de l’autre, vers une harmonie sans cesse à accorder. C’est Scott Fitzgerald qui écrivait : « La marque d’une intelligence de premier plan est qu’elle est capable de se fixer sur deux idées contradictoires sans pour autant perdre la possibilité de fonctionner. On devrait par exemple pouvoir comprendre que les choses sont sans espoir et cependant être décidé à les changer. » Jack Ralite (1928-2017) Ce n’est qu’un début (extrait), in Culture Publique, opus 1 « L’Imagination au pouvoir », Paris, éditions (mouvement) SKITe sens&tonka, 2004. 3 Interpréter, transformer La notion d’interprète constitue le fil rouge de la programmation de ce printemps : dans quel sens interpréter ce terme aujourd’hui dans le Entretien avec Aymar Crosnier, champ chorégraphique ? Et comment est-ce directeur général adjoint en qu’il se déploie dans la programmation ? charge de la programmation Progressivement, se met en place une forme Par Gilles Amalvi de périodicité dans la programmation au CN D. -

Tangoing Gender. Power and Subversion in Argentine Tango

TANGOING GENDER. POWER AND SUBVERSION IN ARGENTINE TANGO. Conference. 10 November 2008. Institute for Cultural Inquiry (ICI) Berlin. Website: http://gendertango.wordpress.com Ute Walter and Marga Nagel Beyond the usual: Experiences and suggestions for the development of a qualitatively different communication culture in Tango. We have been dancing and teaching Tango for over 20 years and today it forms the basis of our livelihood. Our experiences and relationships with this topic are very diverse. Our course participants come from very different background contexts. They are mixed with regard to their sexual orientation and gender identity. This unusual fact alone already brings about a certain awareness process: an interest in and experience with different ways of life, and with this, possibilities for self-change and respecting diversity without making it an explicit theme. As the individual expressiveness of gay and lesbian Tango dancer lifestyles can barely concur with the highly heterosexual relationship model seen in Tango, the heterosexual norm gets disturbed. Most people come with the clear task of wanting to learn ‘authentic’ Argentine Tango. There surely are a high number of Tango dancers who nurture their longing for old role clichés, even though they perhaps refuse these in real everyday life. Also, the relationship to predominant images in Tango is frequently distorted, either through difficulties in converting these physical instructions and especially also on attitude and self-concept levels that pose a contradiction to this. How open our course participants are to further approaches is usually strongly dependant on the fact that they consider us to be competent and authoritative in the field of traditional Argentine Tango. -

The Queer Tango Salon 2017: Dancers Who Think and Thinkers Who Dance

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Roser i Puig, Montserrat (2018) Authentic by Choice, or by Chance? A Discussion of The Gods of Tango, by Carolina de Robertis. In: Batchelor, Ray and Havmøller, Birthe, eds. Queer Tango Salon Lonson 2017 Proceedings. Queer Tango Project, London, UK, pp. 70-81. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/79016/ Document Version Publisher pdf Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Queer Tango Salon London 2017 Proceedings A Queer Tango Project Publication Colophon and Copyright Statement Queer Tango Salon London 2017 - Proceedings Selection and editorial matter © 2018 Ray Batchelor and Birthe Havmøller Written materials © 2018 the individual authors All images and artworks © 2018 the individual artists and photographers This is a Queer Tango Project Publication. -

LE MONDE/PAGES<UNE>

LE MONDE DES LIVRES VENDREDI 4 MAI 2001 LE MONDE DES POCHES UNE VIE DOUCE ÉROTISME : NOIRS PARADIS PENSER HIER POUR PENSER DEMAIN ET TRANQUILLE DE PIONNIER Cinq mille ans d’écrits amoureux Deux volumes collectifs pour tirer le bilan A Québec, une colonie française à la fin par Jean-Jacques Pauvert, philosophique du XXe siècle et envisager du XVIIe, par l’Américaine Willa Cather p. III et quelques curiosités p. VIII des pistes nouvelles pour le XXIe p. X a Viktor Pelevine, Michael Collins, Cuba, Québec, les « Poches » du mois... SUPPLÉMENT AU MONDE DU VENDREDI 4 MAI. N˚ 17503 - DIRECTEUR DE LA PUBLICATION : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI - IMPRIMERIE LE MONDE www.lemonde.fr 57e ANNÉE – Nº 17503 – 7,50 F - 1,14 EURO FRANCE MÉTROPOLITAINE VENDREDI 4 MAI 2001 FONDATEUR : HUBERT BEUVE-MÉRY – DIRECTEUR : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI L’écologie de M. Chirac Enquête sur la folie « Loft Story » b b a Le chef de l’Etat L’émission de « télévision-réalité » de M6 attire massivement les jeunes Prévue pour dix semaines, défend une « écologie elle met en scène la vie intime d’un groupe de garçons et de filles b Coupés du monde, les participants humaniste » ont accepté de fortes contraintes b Exhibitionnisme, voyeurisme, manipulation : le débat fait rage LA CHAÎNE M6 bat tous ses çons (cinq depuis l’abandon de l’un Elle les divise aussi sur la légitimité ter de fortes contraintes : pas de con- qui allierait progrès records d’audience et fait flamber d’entre eux mercredi 2 mai) et cinq de donner à voir un tel spectacle, pré- tacts extérieurs, ni journaux ni ses tarifs publicitaires avec « Loft Sto- filles enfermés et filmés dans un vu pour durer dix semaines. -

TANGO… the Perfect Vehicle the Dialogues and Sociocultural Circumstances Informing the Emergence and Evolution of Tango Expressions in Paris Since the Late 1970S

TANGO… The Perfect Vehicle The dialogues and sociocultural circumstances informing the emergence and evolution of tango expressions in Paris since the late 1970s. Alberto Munarriz A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO March 2015 © Alberto Munarriz, 2015 i Abstract This dissertation examines the various dialogues that have shaped the evolution of contemporary tango variants in Paris since the late 1970s. I focus primarily on the work of a number of Argentine composers who went into political exile in the late 1970s and who continue to live abroad. Drawing on the ideas of Russian linguist Mikhail Bakhtin (concepts of dialogic relationships and polyvocality), I explore the creative mechanisms that allowed these and other artists to engage with a multiplicity of seemingly irreconcilable idioms within the framing concept of tango in order to accommodate their own musical needs and inquietudes. In addition, based on fieldwork conducted in Basel, Berlin, Buenos Aires, Gerona, Paris, and Rotterdam, I examine the mechanism through which musicians (some experienced tango players with longstanding ties with the genre, others young performers who have only recently fully embraced tango) engage with these new forms in order to revisit, create or reconstruct a sense of personal or communal identity through their performances and compositions. I argue that these novel expressions are recognized as tango not because of their melodies, harmonies or rhythmic patterns, but because of the ways these features are “musicalized” by the performers. I also argue that it is due to both the musical heterogeneity that shaped early tango expressions in Argentina and the primacy of performance practices in shaping the genre’s sound that contemporary artists have been able to approach tango as a vehicle capable of accommodating the new musical identities resulting from their socially diverse and diasporic realities. -

Construction D'une Identité Argentine Dans Les Paroles De Tango: Genèse Et Formes Contemporaines

Construction d’une identité argentine dans les paroles de tango : genèse et formes contemporaines Gabriela Constanza Rodriguez To cite this version: Gabriela Constanza Rodriguez. Construction d’une identité argentine dans les paroles de tango : genèse et formes contemporaines. Histoire. Université Toulouse le Mirail - Toulouse II, 2011. Français. NNT : 2011TOU20081. tel-00640819 HAL Id: tel-00640819 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00640819 Submitted on 14 Nov 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Université Toulouse Le Mirail Institut de Recherche Intersite Etudes Culturelles (EA 740) Ecole doctorale Alpha PAR GABRIELA C. RODRIGUEZ CONSTRUCTION D’UNE IDENTITÉ DANS LES PAROLES DE TANGO : GENÈSE ET FORMES CONTEMPORAINES ANNÉE 2010-2011 Sous la direction de Michèle Soriano Université Toulouse Le Mirail Nadia Norah Ghiraldi-Dei Cas Universi té de Lille (Rapporteure) Dardo Scavino Université Versailles Sain-Quentin (Rapporteur) Edmond Cros Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier III Sonia Rosse Université Toulouse Le Mirail 1 Remerciements ŖEl ciclo se ha cerrado. La búsqueda de la identidad es aquí une búsqueda de pasado. Sin embargo, ese hijo de inmigrantes que regresa al espacio de los antepasados, regresa a un espacio que no es suyo: el espacio de una memoria ajena, siempre huidizo.ŗ Rosalba Campra. -

Radio France. France Inter. Archives Papier Des Émissions De Patrice Gélinet « Les Jours Du Siècle » (1996-1999) Et « 2000 Ans D'histoire » (1999-2011)

Radio France. France Inter. Archives papier des émissions de Patrice Gélinet « Les jours du siècle » (1996-1999) et « 2000 ans d'histoire » (1999-2011). 1996-2011 Répertoire numérique détaillé du versement n° 20144583 Établi par Anne Briqueler, Service Archives écrites et Musée - Direction générale déléguée - Radio France Première édition électronique Archives nationales (France) Pierrefitte-sur-Seine 2014 1 https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/IR/FRAN_IR_055856 Cet instrument de recherche a été rédigé avec un logiciel de traitement de texte. Ce document est écrit en français. Conforme à la norme ISAD(G) et aux règles d'application de la DTD EAD (version 2002) aux Archives nationales, il a reçu le visa du Service interministériel des Archives de France le ..... 2 Archives nationales (France) Sommaire Radio France. France Inter. Archives papier des émissions de Patrice Gélinet « Les 9 Jours du siècle » (1996-1999) et « 2000 ans d'histoire » ... Les Jours du siècle 12 Dossiers d'émissions par saison radiophonique 12 Saison 1996-1997 12 1996, semaines 36 à 38 12 1996, semaines 39 à 41 13 1996, semaines 42 à 44 13 1996, semaines 45 à 47 14 1996, semaines 48 à 52 15 1997, semaines 1 à 3 16 1997, semaines 4 à 6 16 1997, semaines 7 à 9 17 1997, semaines 10 à 12 18 1997, semaines 13 à 17 18 1997, semaines 18 à 23 19 1997, semaines 24 à 27 20 Saison 1997-1998 21 1997, semaines 36 à 38 21 1997, semaines 39 à 41 22 1997, semaines 42 à 44 22 1997, semaines 45 à 48 23 1997, semaines 49 à 52 24 1998, semaines 1 à 6 25 1998, semaines -

Being Inappropriate: Queer

BEING INAPPROPRIATE: QUEER ACTIVISM IN CONTEXT By Amy Watson Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts in Gender Studies. Supervisor: Professor Allaine Cerwonka CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2009 Abstract This thesis offers a genealogical approach to queer activism. Starting from the gay liberation movement in the late 1960s, I end with what materialized of queer activism in the form of Queer Nation. Out of theoretical discourse, political events and conceptual problems in the United States, queer activism and theory emerged as a disruption. I depict deliberations of identity as essence and as basis for political action which shifted into the concept of identity as a relational process of practices, as can be seen in the political undertakings of ACT UP. Yet, queer activism is not without its limitations. Specifically, I consider particular practices of Queer Nation as well as mainstream gay and lesbian pride parades. These limitations largely depict queer activism as being class- and race-blind. Moreover, I engage with a critical view of the pink economy and the commodification of queer/gay and lesbian social identities. I take into account the speculation that consumerism has the capacity to depoliticize queer subjects. Contemporary queer activist networks are reformulating as a response to critical engagements with queer activism, the pink economy and a portrayal of the queer subject as commodified. They are engaging in “power-to-do” as part of a relational process. As such, the practices that these sites of activism engage in are indicators that there is an ongoing critique against CEU eTD Collection identity politics, homonormativity and consumerism. -

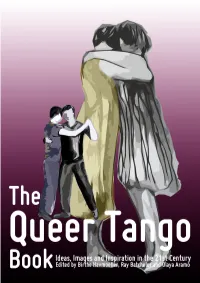

The Queer Tango Book Ideas, Images and Inspiration in the 21St Century

1 Colophon and Copyright Statement Selection and editorial matter © 2015 Birthe Havmoeller, Ray Batchelor and Olaya Aramo Written materials © 2015 the individual authors All images and artworks © 2015 the individual artists and photographers. This publication is protected by copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private research, criticism or reviews, no part of this text may be reproduced, decompiled, stored in or introduced into any website, or online information storage, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without written permission by the publisher. This publication is Free and Non Commercial. When you download this e-book, you have been granted the non-exclusive right to access and read the book using any kind of e-book reader software and hardware or via personal text-to-speech computer systems. You may also share/distribute it for free as long as you give appropriate credit to the editors and do not modify the book. You may not use the materials of this book for commercial purposes. If you remix, transform, or build upon the materials you may NOT distribute the modified material without permission by the individual copyright holders. ISBN 978-87-998024-0-1 (HTML) ISBN 978-87-998024-1-8 (PDF) Published: 2015 by Birthe Havmoeller / Queertangobook.org E-book and cover design © Birthe Havmoeller Text on the cover is designed with 'MISO', a free font made by Mårten Nettelbladt. 2 The Queer Tango Book Ideas, Images and Inspiration in the 21st Century Edited by Birthe Havmoeller, Ray Batchelor and Olaya Aramo In the memory of Ekatarina 'Kot' Khomenko We dedicate this work to the dancers who came before us and to those who will come after. -

Bibliographie Tango-Argentine-Uruguay

Pourquoi cette bibliographie ? Simplement parce que je suis passionnée depuis plus de vingt ans par la culture du Rio de la Plata et que j’aime à partager et si possible rendre plus accessible quelques aspects de cette culture si vaste et si riche auprès des tangueros ou autres curieux en tous genres. Cette bibliographie est un outil. Elle n’est pas exhaustive mais évolutive, perfectible et je l’actualise régulièrement, tant avec les nouvelles parutions que grâce à des contributions extérieures. Vous pourrez la retrouver sans doute sur de nos nombreux sites, mais la mise à jour sera présente sur le site du festival Tangopostale www.tangopostale.com Alors, n’hésitez pas à vous plonger dans ses livres, à en parler, à échanger, à les prêter et les emprunter... Solange Bazely Blog : bandoneonsansfrontiere.blogspot.com Sommaire Livres sur le Tango en français p 2 à 5 Revues sur le Tango en français p 6 à 8 Poésie en français p 9 et 10 Littérature du Rio de la Plata (romans et nouvelles) en français p 11 à 22 BD en français p 23 à 25 Essais, théâtre, documents sur le pays, la ville, l’immigration... p 26 à 33 Livres sur le tango et la culture Rioplatense en espagnol p 34 à 39 Mise à jour 3/12/2014 Bibliographie établie et mise à jour par Solange Bazely 1 Livres sur le Tango (en français) Titre Auteur Editeur ISBN Année Commentaires Le tango de Buenos Aires Claude Fléouter Lattès 79-3-45-0602-8 1979 133 p L’âge d’or du tango : Carlos Edmundo Denoël 978-220723069 1984 224 p Gardel Eichelbaum 5 Le Tango Hommage à Carlos Colloque Université de 2.86513.042.8 1985 302 p - en français et en espagnol Gardel international de Toulouse le Mirail Toulouse les Eché Editeur 13 & 14/11/84 Le tango, action poétique Saúl Yurkevitch Avon 03365816 ISSN 1985 80 p n°100 Annick Havranek Henry Deluy Les poètes du Tango Henry Deluy - Saúl P.O.L. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Social Tango Dancing in the Age of Neoliberal Competition Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6fc7h18z Author Shafie, Radman Publication Date 2019 License CC BY 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Social Tango Dancing in the Age of Neoliberal Competition A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Critical Dance Studies by Radman Shafie June 2019 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Anthea Kraut, Chairperson Dr. Marta Savigliano Dr. Jose Reynoso i Copyright by Radman Shafie 2019 ii The Dissertation of Radman Shafie is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside iii Acknowledgments I have deep gratitude for all the people who made this research possible. I would like to first thank Dr. Anthea Kraut, whose tireless and endless support carried me through the ups and downs of this journey. I am indebted to all the social tango dancers who inspired me, particularly in Buenos Aires, and to those who generously gave me their time and attention. I am grateful for my kind mother, Oranous, who always had my back. And lastly, but far from least, I thank my wife Oldřiška, who whenever I am stuck, magically has a solution. iv To all beings who strive to connect on multiple levels, and find words insufficient to express themselves. v ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Social Tango Dancing in the Age of Neoliberal Competition by Radman Shafie Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in Critical Dance Studies University of California, Riverside, June 2019 Dr. -

Comunicación Académica N° 1682 Nardo Zalko, De San

COMUNICACIÓN ACADÉMICA N° 1682 De la Académica de Número doña Otilia Da Veiga, acerca de NARDO ZALKO, DE SAN CRISTÓBAL A PARÍS Señor Presidente: El servicio latinoamericano de la agencia France-Presse, del que fue jefe hasta su jubilación, emitió el 3 de junio de 2011 la infausta noticia: Nardo Zalko, periodista, escritor e historiador, había fallecido el día anterior a los 69 años tras una triste enfermedad. Hijo de inmigrantes lituanos llegados al país a fines de los años 20 –una época en la que el tango formaba parte de la vida cotidiana–, Zalko nació el 1 de octubre de 1941 en el barrio porteño de San Cristóbal, barrio tanguero por antonomasia, hogar de Francisco Canaro, Vicente Greco y varias familias de músicos notables, donde se bailó el tango en su etapa de música prohibida, como lo cuenta en su libro José Sebastián Tallon. En 1960 dejó la casa natal de la calle Pichincha, y los vientos de la vida lo llevaron hasta la rue de Montorgueil, en París, en la que se afincó para cumplir la parábola de su existencia. Se radicó primero en Israel, donde fue corresponsal del semanario montevideano Marcha y conoció los avatares de la Guerra de los Seis Días, en la que le tocó actuar como paracaidista. En 1970 emigra nuevamente: su destino es París, y allí vive durante cuatro décadas en las que va reencontrándose con el tango que habían captado sus oídos, atesorado en hondos sentimientos. En afán de reconstruir la historia de su ligazón profunda entre Buenos Aires y París, alternó el ejercicio de la profesión periodística con una perseverante, entusiasta e inteligente investigación de las huellas que el tango había dejado en esa ciudad, la cual lo llevó a ser considerado uno de los principales historiadores del género.