Tangoing Gender. Power and Subversion in Argentine Tango

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Queer Tango Salon 2017: Dancers Who Think and Thinkers Who Dance

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Roser i Puig, Montserrat (2018) Authentic by Choice, or by Chance? A Discussion of The Gods of Tango, by Carolina de Robertis. In: Batchelor, Ray and Havmøller, Birthe, eds. Queer Tango Salon Lonson 2017 Proceedings. Queer Tango Project, London, UK, pp. 70-81. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/79016/ Document Version Publisher pdf Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Queer Tango Salon London 2017 Proceedings A Queer Tango Project Publication Colophon and Copyright Statement Queer Tango Salon London 2017 - Proceedings Selection and editorial matter © 2018 Ray Batchelor and Birthe Havmøller Written materials © 2018 the individual authors All images and artworks © 2018 the individual artists and photographers This is a Queer Tango Project Publication. -

Being Inappropriate: Queer

BEING INAPPROPRIATE: QUEER ACTIVISM IN CONTEXT By Amy Watson Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts in Gender Studies. Supervisor: Professor Allaine Cerwonka CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2009 Abstract This thesis offers a genealogical approach to queer activism. Starting from the gay liberation movement in the late 1960s, I end with what materialized of queer activism in the form of Queer Nation. Out of theoretical discourse, political events and conceptual problems in the United States, queer activism and theory emerged as a disruption. I depict deliberations of identity as essence and as basis for political action which shifted into the concept of identity as a relational process of practices, as can be seen in the political undertakings of ACT UP. Yet, queer activism is not without its limitations. Specifically, I consider particular practices of Queer Nation as well as mainstream gay and lesbian pride parades. These limitations largely depict queer activism as being class- and race-blind. Moreover, I engage with a critical view of the pink economy and the commodification of queer/gay and lesbian social identities. I take into account the speculation that consumerism has the capacity to depoliticize queer subjects. Contemporary queer activist networks are reformulating as a response to critical engagements with queer activism, the pink economy and a portrayal of the queer subject as commodified. They are engaging in “power-to-do” as part of a relational process. As such, the practices that these sites of activism engage in are indicators that there is an ongoing critique against CEU eTD Collection identity politics, homonormativity and consumerism. -

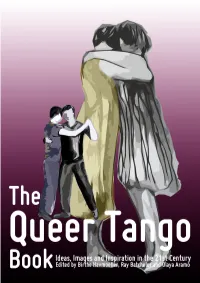

The Queer Tango Book Ideas, Images and Inspiration in the 21St Century

1 Colophon and Copyright Statement Selection and editorial matter © 2015 Birthe Havmoeller, Ray Batchelor and Olaya Aramo Written materials © 2015 the individual authors All images and artworks © 2015 the individual artists and photographers. This publication is protected by copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private research, criticism or reviews, no part of this text may be reproduced, decompiled, stored in or introduced into any website, or online information storage, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without written permission by the publisher. This publication is Free and Non Commercial. When you download this e-book, you have been granted the non-exclusive right to access and read the book using any kind of e-book reader software and hardware or via personal text-to-speech computer systems. You may also share/distribute it for free as long as you give appropriate credit to the editors and do not modify the book. You may not use the materials of this book for commercial purposes. If you remix, transform, or build upon the materials you may NOT distribute the modified material without permission by the individual copyright holders. ISBN 978-87-998024-0-1 (HTML) ISBN 978-87-998024-1-8 (PDF) Published: 2015 by Birthe Havmoeller / Queertangobook.org E-book and cover design © Birthe Havmoeller Text on the cover is designed with 'MISO', a free font made by Mårten Nettelbladt. 2 The Queer Tango Book Ideas, Images and Inspiration in the 21st Century Edited by Birthe Havmoeller, Ray Batchelor and Olaya Aramo In the memory of Ekatarina 'Kot' Khomenko We dedicate this work to the dancers who came before us and to those who will come after. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Social Tango Dancing in the Age of Neoliberal Competition Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6fc7h18z Author Shafie, Radman Publication Date 2019 License CC BY 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Social Tango Dancing in the Age of Neoliberal Competition A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Critical Dance Studies by Radman Shafie June 2019 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Anthea Kraut, Chairperson Dr. Marta Savigliano Dr. Jose Reynoso i Copyright by Radman Shafie 2019 ii The Dissertation of Radman Shafie is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside iii Acknowledgments I have deep gratitude for all the people who made this research possible. I would like to first thank Dr. Anthea Kraut, whose tireless and endless support carried me through the ups and downs of this journey. I am indebted to all the social tango dancers who inspired me, particularly in Buenos Aires, and to those who generously gave me their time and attention. I am grateful for my kind mother, Oranous, who always had my back. And lastly, but far from least, I thank my wife Oldřiška, who whenever I am stuck, magically has a solution. iv To all beings who strive to connect on multiple levels, and find words insufficient to express themselves. v ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Social Tango Dancing in the Age of Neoliberal Competition by Radman Shafie Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in Critical Dance Studies University of California, Riverside, June 2019 Dr. -

Erotic Transgression in Carlos Saura's Tango

EURAMERICA Vol. 50, No. 1 (March 2020), 79-135 DOI: 10.7015/JEAS.202003_50(1).0003 http://euramerica.org Erotic Transgression in Carlos Saura’s Tango* TP PT P P Yuh-Yi Tan Center for General Education, National Taipei University of Business No. 321, Sec. 1, Jinan Rd., Taipei 10051, Taiwan E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Carlos Saura’s musical film Tango, an audio-visual poem, is patterned upon the discourse of the Argentine tango in its pursuit of cultural otherness. The film elucidates the mid-life crisis of writer/director Mario reframed in an erotic site wherein his masculinity is challenged, distressed, and resurrected. With a playful metanarrative attached to love romance and dance spectacle, Tango crosses between the genres of melodrama and dark fantasy to conjure up the weakness of masculine hegemony threatened by murder and sexuality. A genealogy of the erotic via Georges Bataille’s taboo-transgression relation substantiates the perception that Mario’s self is being reconstituted in an erotic and sacrificial rite transpiring on the architectural terrain of tango dance and © Institute of European and American Studies, Academia Sinica Received March 14, 2019; accepted November 4, 2019; last revised December 2, 2019 Proofreaders: Wen-Chi Chang, Chih-Wei Wu, Chia-Chi Tseng * The authoress would like to show her gratitude for the three anonymous reviewers for their insightful suggestions. This article has been sponsored by Ministry of Science and Technology under the name of “Erotic Tango” project (NSC 101- 2410-H-141-011). 80 EURAMERICA musical scenes. In these mise-en-scènes, the subject separates his “other” self from a patriarchal figure with the help of revisionist femme fatales Elena and Laura, as well as with his competitors, Ernesto and Angelo, who challenge him to avoid a living death. -

Notes on Tango (As) Queer (Commodity)

CRITICAL ESSAYS: Marta E. Savigliano: Notes on Tango (as) Queer (Commodity) Notes on Tango (as) Queer (Commodity) Marta E. Savigliano University of California, [email protected] In this paper, I reflect on queer (non-heteronormative) interests in tango. Puzzled, I wonder why tango, an icon of hyper-heteronormative ‘love’, attracts dancers with queer sensibili- ties. In order to begin exploring answers, I look into tango as a commodity, composed of aesthetics and affects, which circulates as a fetish that can be consumed in globalisation unhinged from its socio-cultural moorings, gaining power precisely in its transgressive performance of same gender, counter-heteronormative ‘passion’. I will look into the que- er milongas of Buenos Aires attending to local and foreign dancers, into the presence of same gender dancers in regular Buenos Aires milongas and the traditional milongueros/ as’ responses to male and female tango partnering; and into queer tango expectations sha- red at a conference in Berlin in 2008 and a queer tango festival in Buenos Aires in 2010. Questions throughout, and only begun to be addressed, include: How does capitalism tap into queerness and tango, and how does globalisation enable connecting for marketing and consumption purposes? How is tango marketed to queer culture? How does queer tango intervene in the formation of queer subjectivities at ‘home’ and abroad? And how does it affect local Argentine milonga culture? Tango, (Post)Exoticism, and Globalisation I wish to enumerate the particularities of the tango scene in globalisation before moving to a discussion of queer tango. In doing so, I aim at contextualising the wide circulation of tango lore, of tango dancing practices and beliefs about what tangos stand for, its unique- ness as well as its availability for global consumption. -

The Queer Tango Book –

1 Colophon and Copyright Statement Selection and editorial matter © 2015 Birthe Havmoeller, Ray Batchelor and Olaya Aramo Written materials © 2015 the individual authors All images and artworks © 2015 the individual artists and photographers. This publication is protected by copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private research, criticism or reviews, no part of this text may be reproduced, decompiled, stored in or introduced into any website, or online information storage, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without written permission by the publisher. This publication is Free and Non Commercial. When you download this e-book, you have been granted the non-exclusive right to access and read the book using any kind of e-book reader software and hardware or via personal text-to-speech computer systems. You may also share/distribute it for free as long as you give appropriate credit to the editors and do not modify the book. You may not use the materials of this book for commercial purposes. If you remix, transform, or build upon the materials you may NOT distribute the modified material without permission by the individual copyright holders. ISBN 978-87-998024-0-1 (HTML) ISBN 978-87-998024-1-8 (PDF) Published: 2015 by Birthe Havmoeller / Queertangobook.org E-book and cover design © Birthe Havmoeller Text on the cover is designed with 'MISO', a free font made by Mårten Nettelbladt. 2 The Queer Tango Book Ideas, Images and Inspiration in the 21st Century Edited by Birthe Havmoeller, Ray Batchelor and Olaya Aramo In the memory of Ekaterina 'Kot' Khomenko We dedicate this work to the dancers who came before us and to those who will come after. -

Queer Tango Space Minority Stress, Sexual Potentiality, and Gender Utopias Juliet Mcmains

Queer Tango Space Minority Stress, Sexual Potentiality, and Gender Utopias Juliet McMains Tango Queer, San Telmo, Buenos Aires 16 October 2012 It is nearing 11:00 p.m., still early by tango time, when I duck into the dark entryway at 571 Perú in San Telmo, Buenos Aires’s oldest neighborhood. Once home to Argentina’s wealthy elite, by the early 1900s San Telmo housed the city’s diverse immigrant community. Italians, Russians, English, Spaniards, and Germans were crammed into its many conventillos (tenement houses). Whether it was the poverty, the homesickness, or the shared language of an evolving new music that drew the immigrants together, San Telmo became a crucible for the develop- ment of tango. It was a temporary means of staving off loneliness and despair by throwing one- self into a stranger’s arms as the wail of the bandoneón pressed the pair into motion. By 1912, San Telmo was teeming with tango in its streets, bars, dance halls, and brothels. By 2012, most milongas (tango dances) had moved closer to tourist-oriented venues in the fashionable neigh- borhood of Palermo. However, a few stalwarts remain in San Telmo, including Tango Queer, a Figure 1. Dancers at Tango Queer, Buenos Aires, 2012. (Photo by Léa Hamoignon) TDR: The Drama Review 62:2 (T238) Summer 2018. ©2018 Juliet McMains 59 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/DRAM_a_00748 by guest on 26 September 2021 weekly milonga held since 2007 where the roles of leader and follower are not assigned based on gender. According to founder Mariana Docampo’s manifesto, published in Spanish and English on the Tango Queer website, “we take for granted neither your sexual orientation nor your choice of one role or the other. -

Trouble with Tango: Conversations Across Boundaries Argentine Tango and Contact Improvision

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2016 Trouble with Tango: conversations across boundaries Argentine Tango and contact improvision Eleanor Brickhill University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Brickhill, Eleanor, Trouble with Tango: conversations across boundaries Argentine Tango and contact improvision, Master of Arts - Research thesis, School of Arts, English and Media, University of Wollongong, 2016. -

Argentine Tango and Contact Improvisation

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2016 Argentine tango and contact improvisation Eleanor Brickhill University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Brickhill, Eleanor, Argentine tango and contact improvisation, Master of Arts - Research thesis, Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts, University of Wollongong, 2016. https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/4728 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. -

Interactive Tango Milonga

Interactive Tango Milonga An Interactive Dance System for Argentine Tango Social Dance by Courtney Brown A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved April 2017 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Garth Paine, Chair Sabine Feisst Pavan Turaga ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2017 ABSTRACT “Warning: tango contains highly addictive ingredients, such as pain, pleasure, passion, excitement, connection, freedom, torment, and bliss. In seven out of ten cases it takes over a person's life.” --Naomi Hotta When dancers are granted agency over music, as in interactive dance systems, the actors are most often concerned with the problem of creating a staged performance for an audience. However, as is reflected by the above quote, the practice of Argentine tango social dance is most concerned with participants internal experience and their relationship to the broader tango community. In this dissertation I explore creative approaches to enrich the sense of connection, that is, the experience of oneness with a partner and complete immersion in music and dance for Argentine tango dancers by providing agency over musical activities through the use of interactive technology. Specifically, I create an interactive dance system that allows tango dancers to affect and create music via their movements in the context of social dance. The motivations for this work are multifold: 1) to intensify embodied experience of the interplay between dance and music, individual and partner, couple and community, 2) to create shared experience of the conventions of tango dance, and 3) to innovate Argentine tango social dance practice for the purposes of education and increasing musicality in dancers. -

Queer Festivalsqueer

PROTEST AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS Eleftheriadis Queer Festivals Konstantinos Eleftheriadis Queer Festivals Challenging Collective Identities in a Transnational Europe Queer Festivals Protest and Social Movements Recent years have seen an explosion of protest movements around the world, and academic theories are racing to catch up with them. This series aims to further our understanding of the origins, dealings, decisions, and outcomes of social movements by fostering dialogue among many traditions of thought, across European nations and across continents. All theoretical perspectives are welcome. Books in the series typically combine theory with empirical research, dealing with various types of mobilization, from neighborhood groups to revolutions. We especially welcome work that synthesizes or compares different approaches to social movements, such as cultural and structural traditions, micro- and macro-social, economic and ideal, or qualitative and quantitative. Books in the series will be published in English. One goal is to encourage non- native speakers to introduce their work to Anglophone audiences. Another is to maximize accessibility: all books will be available in open access within a year after printed publication. Series Editors Jan Willem Duyvendak is professor of Sociology at the University of Amsterdam. James M. Jasper teaches at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Queer Festivals Challenging Collective Identities in a Transnational Europe Konstantinos Eleftheriadis Amsterdam University Press The research presented in this book was funded by the IKY Foundation of Greece (State Scholarships Foundation of Greece) and the European University Institute (EUI) in Florence. Cover illustration: During the 2013 Tel Aviv Pride Parade, the anarcho-queer collective ‘Mashpritzot’ held a die-in to protest Israeli pinkwashing, and the homonormative priorities of the city-sposored LGBT center.