Queer Festivalsqueer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Berlin - Wikipedia

Berlin - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berlin Coordinates: 52°30′26″N 13°8′45″E Berlin From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Berlin (/bɜːrˈlɪn, ˌbɜːr-/, German: [bɛɐ̯ˈliːn]) is the capital and the largest city of Germany as well as one of its 16 Berlin constituent states, Berlin-Brandenburg. With a State of Germany population of approximately 3.7 million,[4] Berlin is the most populous city proper in the European Union and the sixth most populous urban area in the European Union.[5] Located in northeastern Germany on the banks of the rivers Spree and Havel, it is the centre of the Berlin- Brandenburg Metropolitan Region, which has roughly 6 million residents from more than 180 nations[6][7][8][9], making it the sixth most populous urban area in the European Union.[5] Due to its location in the European Plain, Berlin is influenced by a temperate seasonal climate. Around one- third of the city's area is composed of forests, parks, gardens, rivers, canals and lakes.[10] First documented in the 13th century and situated at the crossing of two important historic trade routes,[11] Berlin became the capital of the Margraviate of Brandenburg (1417–1701), the Kingdom of Prussia (1701–1918), the German Empire (1871–1918), the Weimar Republic (1919–1933) and the Third Reich (1933–1945).[12] Berlin in the 1920s was the third largest municipality in the world.[13] After World War II and its subsequent occupation by the victorious countries, the city was divided; East Berlin was declared capital of East Germany, while West Berlin became a de facto West German exclave, surrounded by the Berlin Wall [14] (1961–1989) and East German territory. -

Tangoing Gender. Power and Subversion in Argentine Tango

TANGOING GENDER. POWER AND SUBVERSION IN ARGENTINE TANGO. Conference. 10 November 2008. Institute for Cultural Inquiry (ICI) Berlin. Website: http://gendertango.wordpress.com Ute Walter and Marga Nagel Beyond the usual: Experiences and suggestions for the development of a qualitatively different communication culture in Tango. We have been dancing and teaching Tango for over 20 years and today it forms the basis of our livelihood. Our experiences and relationships with this topic are very diverse. Our course participants come from very different background contexts. They are mixed with regard to their sexual orientation and gender identity. This unusual fact alone already brings about a certain awareness process: an interest in and experience with different ways of life, and with this, possibilities for self-change and respecting diversity without making it an explicit theme. As the individual expressiveness of gay and lesbian Tango dancer lifestyles can barely concur with the highly heterosexual relationship model seen in Tango, the heterosexual norm gets disturbed. Most people come with the clear task of wanting to learn ‘authentic’ Argentine Tango. There surely are a high number of Tango dancers who nurture their longing for old role clichés, even though they perhaps refuse these in real everyday life. Also, the relationship to predominant images in Tango is frequently distorted, either through difficulties in converting these physical instructions and especially also on attitude and self-concept levels that pose a contradiction to this. How open our course participants are to further approaches is usually strongly dependant on the fact that they consider us to be competent and authoritative in the field of traditional Argentine Tango. -

The Queer Tango Salon 2017: Dancers Who Think and Thinkers Who Dance

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Roser i Puig, Montserrat (2018) Authentic by Choice, or by Chance? A Discussion of The Gods of Tango, by Carolina de Robertis. In: Batchelor, Ray and Havmøller, Birthe, eds. Queer Tango Salon Lonson 2017 Proceedings. Queer Tango Project, London, UK, pp. 70-81. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/79016/ Document Version Publisher pdf Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Queer Tango Salon London 2017 Proceedings A Queer Tango Project Publication Colophon and Copyright Statement Queer Tango Salon London 2017 - Proceedings Selection and editorial matter © 2018 Ray Batchelor and Birthe Havmøller Written materials © 2018 the individual authors All images and artworks © 2018 the individual artists and photographers This is a Queer Tango Project Publication. -

Diversity & Inclusion Committee

DIVERSITY & INCLUSION COMMITTEE JUNE 2021 EDITION JUNETEENTH: BLACK AMERICANS’ TRUE INDEPENDENCE DAY Juneteenth (short for “June Nineteenth”) is the oldest nationally How To Celebrate Juneteenth: celebrated commemoration of the end of racial slavery in the • Find an event in your United States. It was on June 19, 1965 that Union Army general neighborhood. Gordon Grander proclaimed freedom from slavery in Texas, • Support Black-owned businesses two and a half years after President Abraham Lincoln signed in your community. the Emancipation Proclamation. • Listen to Black musicians. The celebration that once started as a small community • Read works by Black authors and gathering in Texas quickly spread across the South. During the poets. Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, the commemoration grew • Watch Black TV shows and in popularity with a focus in postwar civil rights. movies. • Visit an exhibit or museum Juneteenth is now widely celebrated as a holiday of hope and dedicated to Black culture. a day to celebrate the end of racial slavery in the United States. • Donate to organizations and It is also a time to reflect on what freedom means today and charities. a time of joy to ease the pain, anger and sadness around the continued racial injustice in the United States. • Cook some traditional foods. CENTENNIAL OF THE TULSA RACE MASSACRE What the Juneteenth 100 years ago, America was shaken by one of its deadliest acts colors represent: of racial violence. The Tulsa Race Massacre took place on May • Red: the blood that 31 and June 1, 1921 when White citizens (many given weapons unites all people of by city officials) attacked Black citizens and destroyed homes Black African ancestry, and businesses in Tulsa, Oklahoma. -

Pride Around the World Plan Your Celebrations a Community United

ISSUE # 19 | 05.11.17 ARTUNDRESSED ART + NUDITY 7TH ANNUAL FESTIVAL DESTINATIONS: QUÉBEC FABULOUSLY FRENCH CANADIAN TOP TRAX: EMIN'S MIAMI TOUR FROM RUSSIA WITH LOVE PRIDE AROUND THE WORLD PLAN YOUR CELEBRATIONS A COMMUNITY UNITED DENTAL Insurance Physicians Mutual Insurance Company A less expensive way to help get the dental care you deserve If you’re over 50, you can get coverage for about $1 a day* Keep your own dentist! NO networks to worry about No wait for preventive care and no deductibles – you could get a checkup tomorrow Coverage for over 350 procedures – including cleanings, exams, fi llings, crowns…even dentures NO annual or lifetime cap on the cash benefi ts TABLE OF CONTENTS: you can receive 8. FEATURE: ARTUNDRESSED The fusion of art and sensuality in the form of nudity is explored extensively in the upcoming 7th FREE Information Kit annual ARTundressed Festival and Wire Magazine sat down with acclaimed artist Noel to discuss the occasion. PHOTO BY PETER ARNOW. COURTESY OF KEY WEST PRIDE COURTESY PHOTO BY PETER ARNOW. 14. COVER STORY: PRIDE AROUND THE WORLD Pride is an international experience, so Wire Mag- azine brings you a special issue that offers a look at many of the celebrations dotting the globe. 20. TOP TRAX: FROM RUSSIA WITH LOVE Emin Araz oglu Agalarov (we'll just call him Emin) is about to do what no other Russian male singer has done before – become America's newest pop star – and he's starting with Miami. 1-866-748-4542 22. DESTINATIONS: QUÉBEC www.dental50plus.com/wire Travelers can get all the French immersion and culture they might want much closer to home and enjoy a beneficial currency exchange in Canada's Québec. -

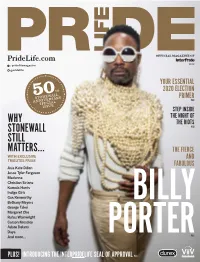

Why Stonewall Still Matters…

PrideLife Magazine 2019 / pridelifemagazine 2019 @pridelife YOUR ESSENTIAL th 2020 ELECTION 50 PRIMER stonewall P.68 anniversaryspecial issue STEP INSIDE THE NIGHT OF WHY THE RIOTS STONEWALL P.50 STILL MATTERS… THE FIERCE WITH EXCLUSIVE AND TRIBUTES FROM FABULOUS Asia Kate Dillon Jesse Tyler Ferguson Madonna Christian Siriano Kamala Harris Indigo Girls Gus Kenworthy Bethany Meyers George Takei BILLY Margaret Cho Rufus Wainwright Carson Kressley Adore Delano Daya And more... PORTERP.46 PLUS! INTRODUCING THE INTERPRIDELIFE SEAL OF APPROVAL P.14 B:17.375” T:15.75” S:14.75” Important Facts About DOVATO Tell your healthcare provider about all of your medical conditions, This is only a brief summary of important information about including if you: (cont’d) This is only a brief summary of important information about DOVATO and does not replace talking to your healthcare provider • are breastfeeding or plan to breastfeed. Do not breastfeed if you SO MUCH GOES about your condition and treatment. take DOVATO. You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should ° You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should HIV-1 to your baby. Know about DOVATO? INTO WHO I AM If you have both human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) and ° One of the medicines in DOVATO (lamivudine) passes into your breastmilk. hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, DOVATO can cause serious side ° Talk with your healthcare provider about the best way to feed your baby. -

Pink Pillow – New Network of Hotels in Berlin

pink pillow – New Network of Hotels in Berlin Berlin, 4 March 2013 | The ITB will be the official launch of the pink pillow Berlin Collection. This new initiative from visitBerlin and the Berlin hotel industry invites hotels to come out as especially welcoming to gay and lesbian visitors to Germany's capital. The pink pillow Berlin Collection provides further evidence that Berlin is a tolerant and open metropolis and one of the world's leading gay travel destinations. That´s why visitBerlin and the Berlin hotel industry wanted to strengthen the city's reputation as an attractive destination for gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) persons. The pink pillow Berlin Collection for the first time sets standards to be identified as especially welcoming. Each participating hotel of the pink pillow Berlin Collection stands for the right that everyone can be the way he wants to be and that every guest should feel safe and welcome. This unique project makes Berlin the first city in the world with a long-term LGBT tourism programme. Burkhard Kieker, CEO of visitBerlin, remarks: "In Berlin, tolerance is practised and all people are free to be themselves. The city has now created something new for the gay and lesbian travel market and has established a unique hotel network." Kicking off with 23 hotels in the pink pillow Berlin Collection The 23 hotels who have joined the pink pillow Berlin Collection at its launch include the nhow Berlin, the Grand Hotel Esplanade Berlin, the Novotel Berlin Am Tiergarten, the Radisson Blu Hotel Berlin, and The Westin Grand Berlin. -

GERMANY Population: 80+ Million Stonewall Global Diversity Champions: 74

STONEWALL GLOBAL WORKPLACE BRIEFINGS 2018 GERMANY Population: 80+ million Stonewall Global Diversity Champions: 74 THE LEGAL LANDSCAPE In Stonewall’s Global Workplace Equality Index, broad legal zoning is used to group the differing challenges faced by organisations across their global operations. Germany is classified as a Zone 1 country, which means sexual acts between people of the same sex are legal and clear national employment protections exist for lesbian, gay, and bi people. Two further zones exist. In Zone 2 countries, sexual acts between people of the same sex are legal but no clear national employment protections exist on grounds of sexual orientation. In Zone 3 countries, sexual acts between people of the same sex are illegal. FREEDOM OF FAMILY AND RELATIONSHIPS EQUALITY AND EMPLOYMENT GENDER IDENTITY IMMIGRATION EXPRESSION, ASSOCIATION AND ASSEMBLY Articles 5, 9 and 8 Sexual acts between people of The Equal Treatment Act The Transgender Law (1980) Section 27 (2) of the of the Constitution the same sex are legal. (2006) provides protection provides trans people the Act on the Residence, protect the general from discrimination on the right to change their legal Economic Activity rights to freedom There is an equal age of grounds of ‘sexual identity’ in name (Section 1) and/or their and Integration of of expression, consent of 14 years for sexual employment and occupation. legal gender to ‘female’ or Foreigners in the association and acts regardless of gender under ‘male’ (Section 8). Federal Territory assembly. Article 176 of the Criminal Code. The same law also provides enables family general protection from Legal gender can be changed reunification of Each of these rights Same-sex marriage was discrimination based on on all identification same-sex couples may be restricted legalised on 01 October 2017 ‘sexual identity’ in civil law documents including the if they are married or under certain specified under Section 1353 of the (Section 19) and in regard to the birth certificate if the legal their partnership is circumstances, Civil Code. -

Tel Aviv Kent Profili İsrail

Tel Aviv Kent Profili İsrail • Şubat 2018 Tel Aviv Kent Profili (İsrail) Coğrafya Tel Aviv, İsrail’in ikinci büyük şehri konumundadır. Şehrin de içinde bulunduğu Guş Dan metropoliten alanı ise ülkenin en büyük kentsel yerleşim alanıdır. Şehir aynı zamanda, Silicon Wadi olarak adlandırılan, ülkenin yeni(likçi) kuruluşlar ülkesi (Start-Up Nation) olarak anılmasını sağlayan ileri teknoloji üretimi yapan kurum ve kuruluşların yer aldığı, İsrail’in kıyı ovasındaki en önemli merkez konumundadır. Şehir, Birlemiş Milletler (BM) nezdinde İsrail’in başkenti konumundadır. Bu nedenle, şehir, çok sayıda dış temsilciliğe de ev sahipliği yapmaktadır. Katar Finans Merkezi tarafından yapılan 2017 tarihli bir çalışmaya göre, Tel Aviv, dünyanın önde gelen finans merkezleri sıralamasında 34. olmuş ve küresel şehir olarak kategorilendirilmiştir. Brookings Ensti- tüsü’nün 2014 tarihli bir çalışmasına göre, şehir, Abu Dabi ve Kuveyt’ten sonra, Ortado- ğu’nun en büyük şehir ekonomisine sahiptir. Şehir, 2012 yılı itibariyle, hayat pahalılığı endeksine göre, dünyanın en pahalı 31. şehri konumundadır. Şehir, hey yıl 2,5 milyon yabancı ziyaretçi ağırlamaktadır. Birçok farklı kuruluş tarafından, Ortadoğu’daki parti / eğlence başkenti olarak anılan Tel Aviv, 24 saat yaşayan bir şehir olarak nitelendirilmek- tedir. İsrail’in Akdeniz’e kıyısı olan şehirlerinden biri olan Tel Aviv; Avrupa, Asya ve Afrika kıtala- rının kesişim noktası olan ve sınırları değişken nitelikteki, Bereketli Hilal, Büyük Suriye, Levant gibi farklı isimlerle anılan tarihi-coğrafi-kültürel bölgenin sınırları içinde yer al- maktadır. Tel Aviv, göreceli olarak düşük toprak verimliliğinin olduğu, kumullarla kaplı bir alanda, Yafa şehrinin eski limanının kuzeyinde kurulmuş olan bir şehirdir. Şehrin ve Guş Dan bölgesinin gelişimi sonucu, Tel Aviv ile Yafa şehirleri arasındaki sınır giderek belirsizleşmiştir. -

30Th ANNIVERSARY 1982 – 2012 2012 Annual Report

International Association of Pride Organizers 30th ANNIVERSARY 1982 – 2012 2012 Annual Report InterPride Inc. – International Association of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex Pride Organizers Founded in 1982, InterPride is the world’s largest organization for organizers of Pride events. InterPride is incorporated in the State of Texas in the USA and is a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organiza- tion under US law. It is funded by membership dues, sponsor- ship, merchandise sales and donations from individuals and organizations. Our Mission InterPride’s mission is to promote Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans- gender and Intersex (LGBTI) Pride on an international level and to encourage diverse com munities to hold and attend Pride Events. InterPride increases networking, communication and education among Pride Organizations. InterPride works together with other LGBTI and Human Rights organizations. InterPride’s relationship with its member organizations is one of advice, guidance and assistance when requested. We do not have any control over, or take responsibility for, the way our member organizations conduct their events. Regional Director reports contained within this Annual Report are the words, personal accounts and opinions of the authors involved and do not necessarily reflect the views of InterPride as an organization. InterPride accepts no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of material contained within. InterPride can be contacted via email [email protected] or via our website. www.interpride.org © 2012 InterPride Inc. Information given in this Annual Report is known to be correct at the time of production September 20th, 2012 2 © InterPride Inc. | www.interpride.org 2012 Annual Report Table of Contents Corporate Governance 4 Executive Committee 4 Regional Directors 4 Regions and Member Organizations 6 InterPride Regions 6 Member Organizations 7 InterPride Inc. -

Media Kit 2021

MEDIA KIT SIEGESSÄULE 2021 L-MAG LGBTI*SIEGESSÄULE Kompass SIEGESSÄULE Gay Guide Online Events 1 Deutschland € 4,90 | Österreich € 5,60 | Schweiz CHF 6,50 | Luxemburg € 5,60 www.L-mag.de | September/Oktober 2020 Das Magazin für Lesben BLACK DYKES MATTER LGBT-Community SIEGESSAUWE ARE QUEER LEBERLIN und Rassismus-Debatte LIEBE IN ZEITEN VON CORONA Paare trotzen der Krise OKTOBER 2020 • SIEGESSAEULE.DE SO SICHTBAR WAR S Dyke-March- Fotos aus 8 Städten Enfant terrible des Deutschpop: Max Goldt im SCHNAUZE VOLL Jahr 1980 Zu Hause in der Subkultur: Von Gothic bis Burlesque König der Wörter: Der Schriftsteller und Musiker Max Goldt WIDERSTAND ZWECKLOS? Nein zum Hass: Künstliche Intelligenz, Cyborgs und Gemeinsam gegen Antisemitismus die Vision einer feministischen Zukunft BERLINS MEISTGELESENES STADTMAGAZIN EXPANDED CONTENT IN ENGLISH Cover 05-2020.indd 1 14.08.20 18:49 01 Cover SIS 10-2020.indd 1 21.09.20 17:40 SIEGESSÄULkompassE SPECIAL BRANDEN- QUEER BERLIN: BURG DAS BRANCHENBUCH SOMMER/HERBSTWINTER/FRÜHJAHR 2020 2018 www.siegessaeule-kompass.de MEHR ADRESSEN! ALS 1.000 2 Table of contents About us, our target market 04 Strengths 06 References Print media 08 SIEGESSÄULE 10 L-MAG 12 SIEGESSÄULE Kompass 14 SIEGESSÄULE Gay Guide Online media 16 SDL-Channel 16 Gay-Channel Events 18 CSD – Christopher Street Day Berlin 18 Lesbian and Gay City Festival Berlin 19 Contact 20 Terms and Conditions Corona-Update 2020 - crisis and opportunity! The worldwide pandemic has not failed to leave its mark on the Special Media publishing house and on our city magazine SIEGESSÄULE in particular. In spring 2020, we had to cope with a decline A few examples: in advertising in the event sector among ot- hers, and had problems getting our magazine • Bars, cafes and clubs that were closed created out to the usual 600 locations in Berlin since covered outdoor areas to display and distribute many of them were closed. -

להורדה Tel Aviv Gay Pride

Get ready to feel fun, free, and fabulous! Tel Aviv is one of the most FREE ENGLISH WALKING TOURS The Annual Tel Aviv Pride Festival welcomes thousands of LGBTQ attractive destinations for LGBTQ visitor in the world, with wonderful visitors and what's most interesting is that there's no gay "quarter" or Bauhaus sunny weather and beautiful sandy beaches, interesting architecture "neighborhood" – the whole city is gay-friendly! באוהאוס Tel-Aviv תל-אביב WHITE CITY Yafo יפו and culture, world-class Mediterranean cuisine, and above all - nonstop On Rothschild Blvd. see the impressive development of Tel nightlife. Designated 'World's Best Gay City' (gaycities.com), Tel Aviv is known Aviv. From a small neighborhood of Jaffa, to a city of eclectic for its accepting and pluralistic nature. The city prides itself on its style "dream buildings", to the 2003 proclaimed UNESCO world Whether you’re in town for the Pride Festival (June) or just for a short TEL AVIV embracing of diversity. heritage site of the "White City". Savor the experience of life in city break, Tel Aviv has plenty to offer, and we’re here to help you make Tel Aviv past and present. the most of it. Every Saturday at 11:00. Meeting point: 46 Rothschild Blvd. (corner of Shadal St.) * For additional information about Bauhaus, contact Tel. 03-5220249 [email protected] GAY VIBE OLD JAFFA (YAFO) This 2 hour tour is fully packed with tales and local legends. The tour covers archeological sites, a view of Tel Aviv from the Crest Garden (Gan Hapisga), the renewed alleys of Old Jaffa, and the picturesque Jaffa port.