Notes on Tango (As) Queer (Commodity)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Poesía Tanguera De Eladia Blázquez: De La Melancolía Tradicional a La Vanguardia Renovadora

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University World Languages and Cultures Theses Department of World Languages and Cultures 11-28-2007 La Poesía Tanguera de Eladia Blázquez: De la Melancolía Tradicional a la Vanguardia Renovadora María Marta López Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/mcl_theses Recommended Citation López, María Marta, "La Poesía Tanguera de Eladia Blázquez: De la Melancolía Tradicional a la Vanguardia Renovadora." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2007. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/mcl_theses/2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of World Languages and Cultures at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in World Languages and Cultures Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LA POESÍA TANGUERA DE ELADIA BLÁZQUEZ: DE LA MELANCOLÍA TRADICIONAL A LA VANGUARDIA RENOVADORA by MARÍA MARTA LÓPEZ Under the Direction of Elena del Río Parra ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to explore and analyze the ars poetica in the work of Eladia Blázquez (1936-2005), and to appreciate to what extent it converges or separates detaches itself from the traditional tango lyrics. Due to her numerous pieces, she is the first and only woman to write both music and lyrics consistently, while proposing a different viewpoint in tone and themes in order to update them to current times. Among them, the major are Buenos Aires, life and identity. The researcher proposes that Blázquez nourished herself on the classics, recreating them while offering new expressive possibilities, shifting at times from their melancholic tone and the moaning sound of the bandoneón, tango’s soul-haunting instrument, to a more hopeful one. -

Holland America's Shore Excursion Brochure

Continental Capers Travel and Cruises ms Westerdam November 27, 2020 shore excursions Page 1 of 51 Welcome to Explorations Central™ Why book your shore excursions with Holland America Line? Experts in Each Destination n Working with local tour operators, we have carefully curated a collection of enriching adventures. These offer in-depth travel for first- Which Shore Excursions Are Right for You? timers and immersive experiences for seasoned Choose the tours that interest you by using the icons as a general guide to the level of activity alumni. involved, and select the tours best suited to your physical capabilities. These icons will help you to interpret this brochure. Seamless Travel Easy Activity: Very light activity including short distances to walk; may include some steps. n Pre-cruise, on board the ship, and after your cruise, you are in the best of hands. With the assistance Moderate Activity: Requires intermittent effort throughout, including walking medium distances over uneven surfaces and/or steps. of our dedicated call center, the attention of our Strenuous Activity: Requires active participation, walking long distances over uneven and steep terrain or on on-board team, and trustworthy service at every steps. In certain instances, paddling or other non-walking activity is required and guests must be able to stage of your journey, you can truly travel without participate without discomfort or difficulty breathing. a care. Panoramic Tours: Specially designed for guests who enjoy a slower pace, these tourss offer sightseeing mainly from the transportation vehicle, with few or no stops, and no mandatory disembarkation from the vehicle Our Best Price Guarantee during the tour. -

The Dance Series from Ortofon Is Now Complete – MC Tango Joins MC Samba & MC Salsa for Almost Sixty Years, Ortofon Has

March, 2007 The dance series from Ortofon is now complete – MC Tango joins MC Samba & MC Salsa For almost sixty years, Ortofon has been at the forefront of music reproduction from analogue records. Throughout the years Ortofon have developed many new and creative designs for the enjoyment of music lovers and audio enthusiasts all over the world. WHY AN ORTOFON MOVING COIL CARTIDGE? Many have asked the question: Why is the sound of a moving coil cartridge so superior to that of a traditional magnetic: The answer in one word is linearity. The patented Ortofon low-impedance, low-output design is inherently linear over the entire audible range. This coupled with unequalled tracking ability and unique diamond profiles combines to deliver a sound previously deemed unattainable. The MC Tango, MC Samba and MC Salsa is a direct result of our endeavours. MC Tango has an elliptical diamond which is cut and polished to Ortofon’s standards, and the output is 0.5 mV. The MC Tango is our MC entry level cartridge with a very high cost/performance ratio. MC Samba and MC Salsa have a tiny, nude Elliptical or Fine Line diamond, mounted on a very light and rigid cantilever. This results in low equivalent stylus tip mass and cantilever compliance on 14 and 15 µm/mN, which means that MC Samba and MC Salsa will give excellent results with virtually any tone arm. The armature has been designed as a tiny lightweight cross, and the coils are mounted at exactly 90 degree to each other (just like the walls of the record groove), which is improving the channel separation. -

Tangoing Gender. Power and Subversion in Argentine Tango

TANGOING GENDER. POWER AND SUBVERSION IN ARGENTINE TANGO. Conference. 10 November 2008. Institute for Cultural Inquiry (ICI) Berlin. Website: http://gendertango.wordpress.com Ute Walter and Marga Nagel Beyond the usual: Experiences and suggestions for the development of a qualitatively different communication culture in Tango. We have been dancing and teaching Tango for over 20 years and today it forms the basis of our livelihood. Our experiences and relationships with this topic are very diverse. Our course participants come from very different background contexts. They are mixed with regard to their sexual orientation and gender identity. This unusual fact alone already brings about a certain awareness process: an interest in and experience with different ways of life, and with this, possibilities for self-change and respecting diversity without making it an explicit theme. As the individual expressiveness of gay and lesbian Tango dancer lifestyles can barely concur with the highly heterosexual relationship model seen in Tango, the heterosexual norm gets disturbed. Most people come with the clear task of wanting to learn ‘authentic’ Argentine Tango. There surely are a high number of Tango dancers who nurture their longing for old role clichés, even though they perhaps refuse these in real everyday life. Also, the relationship to predominant images in Tango is frequently distorted, either through difficulties in converting these physical instructions and especially also on attitude and self-concept levels that pose a contradiction to this. How open our course participants are to further approaches is usually strongly dependant on the fact that they consider us to be competent and authoritative in the field of traditional Argentine Tango. -

The Queer Tango Salon 2017: Dancers Who Think and Thinkers Who Dance

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Roser i Puig, Montserrat (2018) Authentic by Choice, or by Chance? A Discussion of The Gods of Tango, by Carolina de Robertis. In: Batchelor, Ray and Havmøller, Birthe, eds. Queer Tango Salon Lonson 2017 Proceedings. Queer Tango Project, London, UK, pp. 70-81. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/79016/ Document Version Publisher pdf Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Queer Tango Salon London 2017 Proceedings A Queer Tango Project Publication Colophon and Copyright Statement Queer Tango Salon London 2017 - Proceedings Selection and editorial matter © 2018 Ray Batchelor and Birthe Havmøller Written materials © 2018 the individual authors All images and artworks © 2018 the individual artists and photographers This is a Queer Tango Project Publication. -

The Intimate Connection of Rural and Urban Music in Argentina at the Beginning of the Twentieth Century

Swarthmore College Works Spanish Faculty Works Spanish 2018 Another Look At The History Of Tango: The Intimate Connection Of Rural And Urban Music In Argentina At The Beginning Of The Twentieth Century Julia Chindemi Vila Swarthmore College, [email protected] P. Vila Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-spanish Part of the Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Julia Chindemi Vila and P. Vila. (2018). "Another Look At The History Of Tango: The Intimate Connection Of Rural And Urban Music In Argentina At The Beginning Of The Twentieth Century". Sound, Image, And National Imaginary In The Construction Of Latin/o American Identities. 39-90. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-spanish/119 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Spanish Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chapter 2 Another Look at the History of Tango The Intimate Connection of Rural ·and Urban Music in Argentina at the Beginning of the Twentieth Century Julia Chindemi and Pablo Vila Since the late nineteenth century, popular music has actively participated in the formation of different identities in Argentine society, becoming a very relevant discourse in the production, not only of significant subjectivities, but also of emotional and affective agencies. In the imaginary of the majority of Argentines, the tango is identified as "music of the city," fundame ntally linked to the city of Buenos Aires and its neighborhoods. In this imaginary, the music of the capital of the country is distinguished from the music of the provinces (including the province of Buenos Aires), which has been called campera, musica criolla, native, folk music, etc. -

El Tango Y La Cultura Popular En La Reciente Narrativa Argentina

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2018 El tango y la cultura popular en la reciente narrativa argentina Monica A. Agrest The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2680 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EL TANGO Y LA CULTURA POPULAR EN LA RECIENTE NARRATIVA ARGENTINA by Mónica Adriana Agrest A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Latin American, Iberian and Latino Cultures in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 MÓNICA ADRIANA AGREST All Rights Reserved ii EL TANGO Y LA CULTURA POPULAR EN LA RECIENTE NARRATIVA ARGENTINA by Mónica Adriana Agrest This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Latin American, Iberian and Latino Cultures in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________________ ________________________________________ November 16th, 2017 Malva E. Filer Chair of Examining Committee ________________________________________ ________________________________________ November 16th, 2017 Fernando DeGiovanni Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Silvia Dapía Nora Glickman Margaret E. Crahan THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT EL TANGO Y LA CULTURA POPULAR EN LA RECIENTE NARRATIVA ARGENTINA by Mónica Adriana Agrest Advisor: Malva E. Filer The aim of this doctoral thesis is to show that Tango as scenario, background, atmosphere or lending its stanzas and language, helps determine the tone and even the sentiment of disappointment and nostalgia, which are in much of Argentine recent narrative. -

Yo Soy El Tango

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES Melanie Carolina Mertz Matrikelnummer: 9902134 Stkz: A 353 590 S YO SOY EL TANGO Descripción de la figura tanguera en su primera época (1900-1930) a través del yo-narrativo en las letras de tango Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des Magistergrades der Philosophie aus der Studienrichtung LA Spanisch eingereicht an der Geistes- und Kulturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Wien bei o. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Michael Metzeltin Wien, 2005 Índice Introducción .................................................................. 4 1. El tango...................................................................... 5 1.1. La historia del tango........................................................... 5 1.2. El lunfardo....................................................................... 18 1.3. Textos primarios y literatura secundaria .......................... 21 1.3.1. Corpus ...........................................................................21 1.3.2. Enfoque teórico .............................................................22 2. El yo-narrativo: narrador y personaje tanguero ......... 24 2.1. Introducción al yo en el tango........................................... 24 2.1.1. Tango y ritual ................................................................25 2.1.2. El gran tango universal ..................................................26 2.1.3. Ficcionalización en el tango...........................................28 2.2. Yo en las constelaciones -

Catálogo De Documentales Uruguayos

Por primera vez se realiza en Uruguay un encuentro For the first time in Uruguay we have an international internacional dedicado especialmente a la producción meeting dedicated specifically to documentaries. It brings documental, que reúne a televisoras y productores latino- together Latin American television representatives and americanos con la intención de construir redes de coopera- producers, and the aim is to construct networks for ción, intercambio y coproducción. Esa convocatoria motivó cooperation, sharing and co-production. This event a los organizadores de DocMontevideo a proponer una prompted the organizers of DocMontevideo to propose a recopilación de nuestra propia producción. En esa iniciati- compilation of our own documentaries, and this collection va está el origen del presente trabajo. is the fruit of that initiative. Como forma de explicitar el criterio que adoptamos a Our criteria for selecting material for this collection was la hora de seleccionar el material, vayan las siguientes to take documentaries made since 1985 that, in the aclaraciones: el catálogo reúne los documentales realiza- broadest sense, deal with Uruguayan subjects. We excluded dos desde 1985 a la fecha, que abordan, en sentido amplio, work from before that year, films of less than 25 minutes temas uruguayos. Excluimos las producciones anteriores a duration, documentary series and productions from schools esa fecha, las que tienen una duración inferior a 25', las of cinema or communications. Although we carried out series documentales y las realizaciones de escuelas de cine exhaustive research we may possibly have overlooked some y comunicación. Aunque la investigación fue exhaustiva, documentaries produced in the period, but we feel that the es posible que no hayamos alcanzado a relevar todas las 81 films in the collection provide an excellent sample of what obras producidas en el período. -

Being Inappropriate: Queer

BEING INAPPROPRIATE: QUEER ACTIVISM IN CONTEXT By Amy Watson Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts in Gender Studies. Supervisor: Professor Allaine Cerwonka CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2009 Abstract This thesis offers a genealogical approach to queer activism. Starting from the gay liberation movement in the late 1960s, I end with what materialized of queer activism in the form of Queer Nation. Out of theoretical discourse, political events and conceptual problems in the United States, queer activism and theory emerged as a disruption. I depict deliberations of identity as essence and as basis for political action which shifted into the concept of identity as a relational process of practices, as can be seen in the political undertakings of ACT UP. Yet, queer activism is not without its limitations. Specifically, I consider particular practices of Queer Nation as well as mainstream gay and lesbian pride parades. These limitations largely depict queer activism as being class- and race-blind. Moreover, I engage with a critical view of the pink economy and the commodification of queer/gay and lesbian social identities. I take into account the speculation that consumerism has the capacity to depoliticize queer subjects. Contemporary queer activist networks are reformulating as a response to critical engagements with queer activism, the pink economy and a portrayal of the queer subject as commodified. They are engaging in “power-to-do” as part of a relational process. As such, the practices that these sites of activism engage in are indicators that there is an ongoing critique against CEU eTD Collection identity politics, homonormativity and consumerism. -

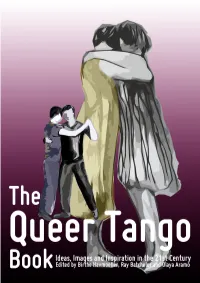

The Queer Tango Book Ideas, Images and Inspiration in the 21St Century

1 Colophon and Copyright Statement Selection and editorial matter © 2015 Birthe Havmoeller, Ray Batchelor and Olaya Aramo Written materials © 2015 the individual authors All images and artworks © 2015 the individual artists and photographers. This publication is protected by copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private research, criticism or reviews, no part of this text may be reproduced, decompiled, stored in or introduced into any website, or online information storage, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without written permission by the publisher. This publication is Free and Non Commercial. When you download this e-book, you have been granted the non-exclusive right to access and read the book using any kind of e-book reader software and hardware or via personal text-to-speech computer systems. You may also share/distribute it for free as long as you give appropriate credit to the editors and do not modify the book. You may not use the materials of this book for commercial purposes. If you remix, transform, or build upon the materials you may NOT distribute the modified material without permission by the individual copyright holders. ISBN 978-87-998024-0-1 (HTML) ISBN 978-87-998024-1-8 (PDF) Published: 2015 by Birthe Havmoeller / Queertangobook.org E-book and cover design © Birthe Havmoeller Text on the cover is designed with 'MISO', a free font made by Mårten Nettelbladt. 2 The Queer Tango Book Ideas, Images and Inspiration in the 21st Century Edited by Birthe Havmoeller, Ray Batchelor and Olaya Aramo In the memory of Ekatarina 'Kot' Khomenko We dedicate this work to the dancers who came before us and to those who will come after. -

El Tango En La Medicina

UNIVERSIDAD DE LA REPÚBLICA Facultad de Medicina Departamento de Historia de la Medicina Con motivo de una nueva edición del Día del Patrimonio 2013 El tango en la Medicina Br. Mariángela Santurio Scocozza, Gr. 1 Docente Ayudante Depto. Historia de la Med 0 Algunas consideraciones previas: Agradezco la posibilidad de haber llevado a cabo esta actividad, es mi segunda participación en el recorrido, siendo la primera en la organización de la coordinación. A las autoridades de la Facultad, Secretaria Sra. Laura Mariño, al Dr. Gustavo Armand Ugónd, del Servicio de Anatomía, al personal de Biblioteca, en nombre de la Lic. Mercedes Surroca, y la invalorable colaboración de la Lic. Amparo de los Santos. Al personal de Historia de la Medicina, Prof. Em. Dr. Fernando Mañé Garzón, Prof. Aste. Dra. Sandra Burgues Roca, Adms. Marianela Ramírez y Romina Villoldo. Al personal de Vigilancia y Recursos Humanos. Al Sr. Moris “Pocho Zibil”, un estudioso del tema, estimado vecino y floridense de ley. Muy especialmente al Dr. Ricardo Pou Ferrari, Presidente de la Sociedad Uruguaya de Historia de la Medicina, por sus generosos aporte. A todos ellos, gracias por su colaboración… 1 Con motivo de haberse llevado a cabo una nueva edición del Día del Patrimonio (sábado 5 y domingo 6 de octubre), dedicado en esta ocasión a “El Tango ”, y en el marco de la denominación de Montevideo, como Capital Iberoamericana de la Cultura, la Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad de la República, atenta a la importancia de esta temática, ha decido ser partícipe de tal evento, para ello, se me ha propuesto coordinar las actividades del mismo.