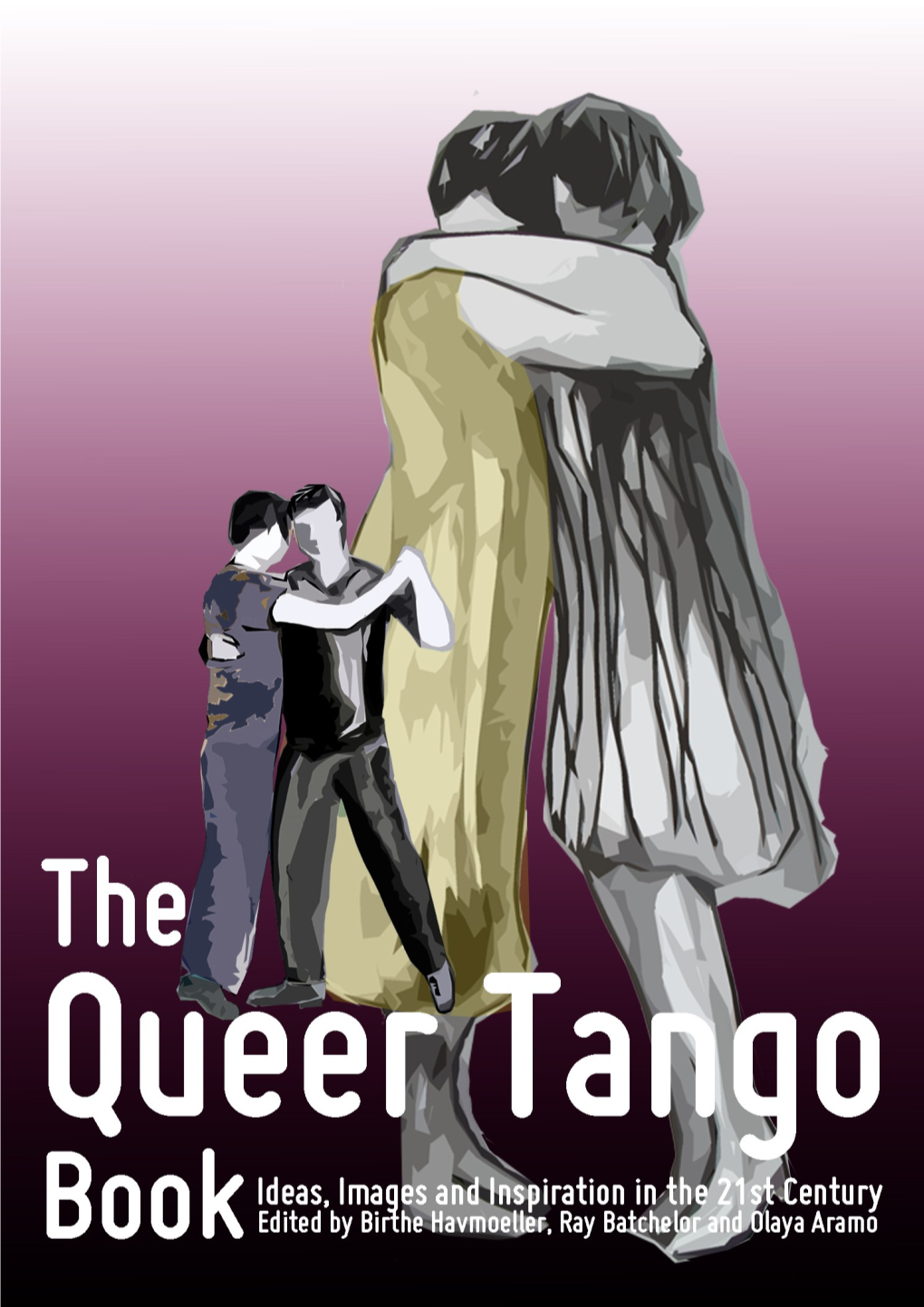

The Queer Tango Book –

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PARIS VISION 2018 5 6 Sur Lascèneinternationale

Paris vision Commerces Gotan Eterno 2018 4 ÉDITO Chers amis, net regain d’optimisme des ménages, du retour des touristes et de l’arrivée en J’ai le plaisir de vous présenter France de nouvelles enseignes étrangères. Paris Vision 2018. Five Guys est l’un de ces acteurs, dans C’est une édition toute particulière car un secteur très en vogue, celui de la nous fêtons le dixième anniversaire de restauration. Philippe Cebral, son Directeur cette publication, qui avait vu le jour la du Développement, détaille dans ces première fois en 2008 dans un tout autre pages la stratégie immobilière du nouveau environnement de marché, j’allais dire à roi des burgers et ses ambitions pour les une autre époque. années à venir. Le projet d’origine était simple : produire Le marché locatif des bureaux en Île- une étude différente, vivante, fidèle à la de-France est au diapason, avec un réalité du terrain vécue par les équipes de volume placé au plus haut depuis 2007 Knight Frank, mais aussi par nos clients, et une activité particulièrement intense qui ont bien voulu chaque année nous sur le créneau des grandes transactions. PHILIPPE PERELLO livrer leur vision et nous en dire plus sur L’accélération de l’activité économique Associé Gérant leur stratégie. Qu’ils en soient tous ici a sans aucun doute joué son rôle. La Knight Frank France chaleureusement remerciés. croissance française est désormais en ligne avec la moyenne européenne, le monde Le deuxième objectif de Paris Vision des affaires a retrouvé la confiance, et Paris était de livrer une analyse prospective s’est vu attribuer l’organisation des Jeux s'inscrivant dans un temps long. -

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

FEATURE PRESENTATION • G1 CHAMPAGNE S. Her Second Trip to the Bluegrass Ended a Lot Happier Than Did Her First

SUNDAY, OCTOBER 10, 2010 For information about TDN, call 732-747-8060. PROVISO STREAKS HOME IN FIRST LADY FEATURE PRESENTATION • G1 CHAMPAGNE S. Her second trip to the Bluegrass ended a lot happier than did her first. Disqualified from the victory in last year=s GI Spinster S., Juddmonte Farm=s Proviso (GB) (Dansili {GB}) un- leashed a furious rally from eighth entering the Keeneland stretch and charged past C. S. Silk (Medaglia d=Oro) for a half- length tally in the GI Abu SAY UNCLE Coady Photography Repole Stables= Uncle Mo (Indian Charlie) proved that Dhabi First Lady S. As to his towering debut success on the Travers Day whether a start against Goldikova (Ire) (Anabaa) in the undercard Aug. 28 was no fluke, GI Breeders= Cup Mile is in the offing, Juddmonte=s attending a very strong pace be- Garrett O=Rourke said, AIt=s our home turf. It=s obviously fore dusting his rivals in the going to be up entirely to what [trainer] Bill [Mott] rec- stretch to take the GI Cham- ommends and what Prince Khalid [Abdullah] wants to pagne S. by a commanding do.@ Cont. p2 4 3/4 lengths. The final time of 1:34.51 was a tick off Devil=s QUALITY ROAD TO Bag=s 1983 stakes record, and STAND AT LANE’S END equaled that of the 1976 winner Edward Evans=s homebred Horsephotos --Seattle Slew. Cont. p2 Quality Road (Elusive Quality-- Kobla, by Mt. Livermore) will Saturday, Belmont Park retire to stud in 2011 and will CHAMPAGNE S.-GI, $300,000, BEL, 10-9, 2yo, 1m, stand at William S. -

Cisco SCA BB Protocol Reference Guide

Cisco Service Control Application for Broadband Protocol Reference Guide Protocol Pack #60 August 02, 2018 Cisco Systems, Inc. www.cisco.com Cisco has more than 200 offices worldwide. Addresses, phone numbers, and fax numbers are listed on the Cisco website at www.cisco.com/go/offices. THE SPECIFICATIONS AND INFORMATION REGARDING THE PRODUCTS IN THIS MANUAL ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE. ALL STATEMENTS, INFORMATION, AND RECOMMENDATIONS IN THIS MANUAL ARE BELIEVED TO BE ACCURATE BUT ARE PRESENTED WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED. USERS MUST TAKE FULL RESPONSIBILITY FOR THEIR APPLICATION OF ANY PRODUCTS. THE SOFTWARE LICENSE AND LIMITED WARRANTY FOR THE ACCOMPANYING PRODUCT ARE SET FORTH IN THE INFORMATION PACKET THAT SHIPPED WITH THE PRODUCT AND ARE INCORPORATED HEREIN BY THIS REFERENCE. IF YOU ARE UNABLE TO LOCATE THE SOFTWARE LICENSE OR LIMITED WARRANTY, CONTACT YOUR CISCO REPRESENTATIVE FOR A COPY. The Cisco implementation of TCP header compression is an adaptation of a program developed by the University of California, Berkeley (UCB) as part of UCB’s public domain version of the UNIX operating system. All rights reserved. Copyright © 1981, Regents of the University of California. NOTWITHSTANDING ANY OTHER WARRANTY HEREIN, ALL DOCUMENT FILES AND SOFTWARE OF THESE SUPPLIERS ARE PROVIDED “AS IS” WITH ALL FAULTS. CISCO AND THE ABOVE-NAMED SUPPLIERS DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES, EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, THOSE OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT OR ARISING FROM A COURSE OF DEALING, USAGE, OR TRADE PRACTICE. IN NO EVENT SHALL CISCO OR ITS SUPPLIERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY INDIRECT, SPECIAL, CONSEQUENTIAL, OR INCIDENTAL DAMAGES, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, LOST PROFITS OR LOSS OR DAMAGE TO DATA ARISING OUT OF THE USE OR INABILITY TO USE THIS MANUAL, EVEN IF CISCO OR ITS SUPPLIERS HAVE BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES. -

Transgender-Identiti

Transgender Identities Overview Transgender is an umbrella term for a wide variety of identities describing an individual’s embodiment or gender presentation challenging the cultural or societal norm of their assigned sex at birth. An individual can identify as one or many of these identities. “Trans” is shorthand for “transgender.” Terminology has changed over time so we need to be sensitive to usage within particular communities. Gender Identity: An individual’s internal sense of Bi-Gendered: One who has a significant gender being male, female, or something beyond the binary. identity encompassing both male and female Gender identity is internal; ones gender identity is genders. Some may feel one side is stronger, but not necessarily visible to others. both sides are engaged. Gender Expression: How a person represents or Two-Spirit: Contemporary term referring to the expresses their gender identity to others, often historical and current First Nations people whose through behavior, clothing, hairstyles, voice or body individuals spirits were a blend of male and female characteristics. spirits. This term has been reclaimed by some Native American LGBT communities to honor their Intersex: Term used for people who are born with heritage and provide an alternative to the Western reproductive or sexual anatomy and/or chromosome labels of gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender. patter that dos not align with typical definitions of male or female. Cross-Dresser: A term used for an individual who dress in clothing traditionally or stereotypically worn Transsexual: An older term for people whose by the other sex, but generally do not have an intent gender identity is different from their assigned sex at to live full-time as the other gender. -

Tangoing Gender. Power and Subversion in Argentine Tango

TANGOING GENDER. POWER AND SUBVERSION IN ARGENTINE TANGO. Conference. 10 November 2008. Institute for Cultural Inquiry (ICI) Berlin. Website: http://gendertango.wordpress.com Ute Walter and Marga Nagel Beyond the usual: Experiences and suggestions for the development of a qualitatively different communication culture in Tango. We have been dancing and teaching Tango for over 20 years and today it forms the basis of our livelihood. Our experiences and relationships with this topic are very diverse. Our course participants come from very different background contexts. They are mixed with regard to their sexual orientation and gender identity. This unusual fact alone already brings about a certain awareness process: an interest in and experience with different ways of life, and with this, possibilities for self-change and respecting diversity without making it an explicit theme. As the individual expressiveness of gay and lesbian Tango dancer lifestyles can barely concur with the highly heterosexual relationship model seen in Tango, the heterosexual norm gets disturbed. Most people come with the clear task of wanting to learn ‘authentic’ Argentine Tango. There surely are a high number of Tango dancers who nurture their longing for old role clichés, even though they perhaps refuse these in real everyday life. Also, the relationship to predominant images in Tango is frequently distorted, either through difficulties in converting these physical instructions and especially also on attitude and self-concept levels that pose a contradiction to this. How open our course participants are to further approaches is usually strongly dependant on the fact that they consider us to be competent and authoritative in the field of traditional Argentine Tango. -

The Queer Tango Salon 2017: Dancers Who Think and Thinkers Who Dance

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Roser i Puig, Montserrat (2018) Authentic by Choice, or by Chance? A Discussion of The Gods of Tango, by Carolina de Robertis. In: Batchelor, Ray and Havmøller, Birthe, eds. Queer Tango Salon Lonson 2017 Proceedings. Queer Tango Project, London, UK, pp. 70-81. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/79016/ Document Version Publisher pdf Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Queer Tango Salon London 2017 Proceedings A Queer Tango Project Publication Colophon and Copyright Statement Queer Tango Salon London 2017 - Proceedings Selection and editorial matter © 2018 Ray Batchelor and Birthe Havmøller Written materials © 2018 the individual authors All images and artworks © 2018 the individual artists and photographers This is a Queer Tango Project Publication. -

A Look at 'Fishy Drag' and Androgynous Fashion: Exploring the Border

This is a repository copy of A look at ‘fishy drag’ and androgynous fashion: Exploring the border spaces beyond gender-normative deviance for the straight, cisgendered woman. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/121041/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Willson, JM orcid.org/0000-0002-1988-1683 and McCartney, N (2017) A look at ‘fishy drag’ and androgynous fashion: Exploring the border spaces beyond gender-normative deviance for the straight, cisgendered woman. Critical Studies in Fashion and Beauty, 8 (1). pp. 99-122. ISSN 2040-4417 https://doi.org/10.1386/csfb.8.1.99_1 (c) 2017, Intellect Ltd. This is an author produced version of a paper published in Critical Studies in Fashion and Beauty. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 JACKI WILLSON University of Leeds NICOLA McCARTNEY University of the Arts, London and University of London A look at ‘fishy drag’ and androgynous fashion: Exploring the border spaces beyond gender-normative deviance for the straight, cisgendered woman Abstract This article seeks to re-explore and critique the current trend of androgyny in fashion and popular culture and the potential it may hold for gender deviant dress and politics. -

Moses in Switzerland | Norient.Com 25 Sep 2021 03:01:16 Moses in Switzerland PODCAST by Moses Iten

Moses in Switzerland | norient.com 25 Sep 2021 03:01:16 Moses in Switzerland PODCAST by Moses Iten In the philosophical DJ-Set «The B Side of Switzerland» and the radio Podcast «Stranger than caribbean music: My swiss roots» the swiss-australian artist Moses Iten travelles through Switzerland and back to his own swiss past. Based in Melbourne he is gaining an international reputation as a DJ and producer with the Cumbia Cosmonauts – a fresh outlook to search for remains and revivals of «real» Swiss folk music. The B Side of Switzerland Swiss-Australian artist Moses Iten recently travelled around the tiny nation of Switzerland by bus, train, plane and steamship, along the way digging in record stores for forgotten classics, cult jewels, experimental gems, and interviewing some of the artists behind music Made in Switzerland. Moses introduces us to the likes of a man who spent ten years recording the sounds of steamboats; a spaghetti western soundtrack composer; a son of yodellers who is a well-known dancehall producer; and a duo of like-minded sonic explorers sharing some of their insights. This road trip through the sonic landscape of Switzerland is the B-Side to a documentary Moses produced for Into The Music, which explored his quest as a musician of how to best produce contemporary music that is https://norient.com/podcasts/moses-in-switzerland Page 1 of 7 Moses in Switzerland | norient.com 25 Sep 2021 03:01:16 representative of his birth country. In this B-Side version, Switzerland and its music is ripped apart and put together again without paying much attention to tradition or history, but sense of place remains all-important in this philosophical DJ set. -

Ww10online1.Pdf

First Masses of School Year St. Thomas More Newman Center Sunday 10am-11am Austin M. Schafer September 19 [email protected] , Residence Hall 614.291.4674 http://www.buckeyecatholic.com/mass-times Move-In All Over Campus // 8am-3pm The St. Thomas More Newman Center and Catholic Students Association welcomes all [email protected] to attend the First Mass of the School Year. http://housing.osu.edu/ Sat @ 5:30 p.m. Sun. @ 10 a.m., Noon, 6 Behold the legendary move-in process that p.m., 9 p.m. Location: 64 W Lane Ave. OSU families have raved about for years! Prepare to be amazed as our student Ohio Welcome Week State Welcome Leaders (OWLs) help you Photo Op take your luggage, gadgets, and goodies up Ohio Union, 12pm-6pm to your room with lightning speed. Sponsored by the Office of Student Life. Erica Baumker [email protected], 419.270.2123 http://www.ohiostatealumni.org/sac Student-Alumni Council welcomes you to The Ohio State University! Capture your move-in day experience with a commemorative photo outside the Alumni Association Office on the first floor of the Ohio Union. Honors & Scholars Move In Day Open House Kuhn Honors & Scholars House 2pm-4:30pm Vicki Pitstick [email protected], 614.292.1794 Honors & Scholars students and their family members are invited to come by the Kuhn Buckeye Prize Brigade Honors & Scholars House to enjoy some Various Locations // 10am-1pm refreshments, meet other Honors & Scholars students, and mingle with the staff. Sharrell Hassell-Goodman [email protected], 614.247.8609 It’s -

Le Cas Paris-Buenos Aires Charlotte Renaudat Ravel

Villes Capitales et dialogues interculturels : dispositifs, lieux et médiations thématiques : le cas Paris-Buenos Aires Charlotte Renaudat Ravel To cite this version: Charlotte Renaudat Ravel. Villes Capitales et dialogues interculturels : dispositifs, lieux et médiations thématiques : le cas Paris-Buenos Aires. Sciences de l’information et de la communication. 2019. dumas-02530212 HAL Id: dumas-02530212 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02530212 Submitted on 2 Apr 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright Master professionnel Mention : Information et communication Spécialité : Communication Entreprises et institutions Option : Entreprises, institutions, culture et tourisme Villes Capitales et dialogues interculturels : dispositifs, lieux et médiations thématiques Le cas Paris - Buenos Aires Responsable de la mention information et communication Professeure Karine Berthelot-Guiet Tuteur universitaire : Dominique Pagès Nom, prénom : RENAUDAT RAVEL Charlotte Promotion : 2018 Soutenu le : 18/06/2019 Mention du mémoire : Très bien École des hautes études en sciences de l'information et de la communication – Sorbonne Université 77, rue de Villiers 92200 Neuilly-sur-Seine I tél. : +33 (0)1 46 43 76 10 I fax : +33 (0)1 47 45 66 04 I celsa.fr TABLE DES MATIÈRES REMERCIEMENTS 2 DOMAINES D’INVESTIGATION ET MOTS CLÉS 4 INTRODUCTION 5 Dispositifs de médiation interculturelle entre les villes-mondes : la construction d’un regard sur l’autre dans le paysage urbain 13 A. -

Memoria Y Representación Audiovisual De Las Prácticas Travestis

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA INFORMACIÓN TESIS DOCTORAL Memoria y representación audiovisual de las prácticas travestis, transformistas y drag queens, de los carnavales de Barranquilla, Baranoa, Puerto Colombia y Santo Tomás en el Caribe colombiano MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTOR PRESENTADA POR Danny Armando González Cueto Director Francisco A. Zurian Madrid Ed. electrónica 2019 © Danny Armando González Cueto, 2019 DOCTORADO EN COMUNICACIÓN AUDIOVISUAL, PUBLICIDAD Y RELACIONES PÚBLICAS FACULTAD DE CC. DE LA INFORMACIÓN TESIS DOCTORAL Memoria y representación audiovisual de las prácticas travestis, transformistas y drag queens, de los carnavales de Barranquilla, Baranoa, Puerto Colombia y Santo Tomás en el Caribe colombiano Autor: Danny Armando González Cueto Director: Prof. Dr. Francisco A. Zurian Fecha: Madrid, 2019. AGRADECIMIENTOS Durante cuatro años se desarrolló esta investigación, que desafió mi manera de ver el mundo, debido también a que esta experiencia llena de novedades, tuvo como epicentro la ciudad de Madrid, en España, un fuerte contraste con el mundo del trópico del que provengo, por lo cual el proceso de adaptación fue fundamental para profundizar en el proyecto. Por eso, quiero agradecer en especial a Madrid, por su acogida, sus librerías, su Feria del Libro, sus parques, sus cines, sus espacios para el ocio, su particular forma de ser cómplice cuando el tiempo de una conversación se hizo interminable, y a las amigas y a los amigos que aquí me abrazaron y me permitieron crear en la tertulia nocturna. Expreso mi agradecimiento a mi director, el profesor Francisco A. Zurian, por tener la dedicación, la paciencia y la sabiduría para orientar este proceso de investigación, llevándolo más allá del mero hecho de lograrlo, alentándome en publicar artículos, apoyarle en proyectos editoriales, en la organización de eventos y muy importante, ser capaz de que el discurso y el enunciado devenido de mi visión sobre las cosas, se hiciera fuerte y decidido.