“The Only True People” Linking Maya Identities Past and Present “The Only True People”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Toltec Invasion and Chichen Itza

Other titles of interest published by Thames & Hudson include: Breaking the Maya Code Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs Angkor and the Khmer Civilization India: A Short History The Incas The Aztecs See our websites www.thamesandhudson.com www.thamesandhudsonusa.com 7 THE POSTCLASSIC By the close of the tenth century AD the destiny of the once proud and independent Maya had, at least in northern Yucatan, fallen into the hands of grim warriors from the highlands of central Mexico, where a new order of men had replaced the supposedly more intellectual rulers of Classic times. We know a good deal about the events that led to the conquest of Yucatan by these foreigners, and the subsequent replacement of their state by a resurgent but already decadent Maya culture, for we have entered into a kind of history, albeit far more shaky than that which was recorded on the monuments of the Classic Period. The traditional annals of the peoples of Yucatan, and also of the Guatemalan highlanders, transcribed into Spanish letters early in Colonial times, apparently reach back as far as the beginning of the Postclassic era and are very important sources. But such annals should be used with much caution, whether they come to us from Bishop Landa himself, from statements made by the native nobility, or from native lawsuits and land claims. These are often confused and often self-contradictory, not least because native lineages seem to have deliberately falsified their own histories for political reasons. Our richest (and most treacherous) sources are the K’atun Prophecies of Yucatan, contained in the “Books of Chilam Balam,” which derive their name from a Maya savant said to have predicted the arrival of the Spaniards from the east. -

North American Academic Research Introduction

+ North American Academic Research Journal homepage: http://twasp.info/journal/home Research Between the Forest and the Village: the New Social Forms of the Baka’s Life in Transition Richard Atimniraye Nyelade 1,2* 1This article is an excerpt of my Master thesis in Visual Cultural Studies defended at the University of Tromso in Norway in December 2015 under the supervision of Prof Bjørn Arntsen 2Research Officer, Institute of Agricultural Research for Development, P.O.Box 65 Ngaoundere, Cameroon; PhD student in sociology, University of Shanghai, China *Corresponding author [email protected] Accepted: 29 February , 2020; Online: 07 March, 2020 DOI : https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3700533 Abstract: The Baka are part of hunter-gatherers group of central Africa generally called “pygmies”. They are most often presented as an indigenous, monolithic and marginalised entity. After a fieldwork carried out in Nomedjoh village in South-Easthern Cameroon, audiovisual and qualitative data have been collected. The theoretical framework follows the dichotomy between structuralism and constructivism. While the former considers identity as a sum of artefacts identifiable and transmissible from generation to generation, the latter, notably with Fredrik Barth, defines ethnicity as a heterogeneous and dynamic entity that changes according to the time and space. Beyond this controversy, the data from Nomedjoh reveal that the Baka community is characterised by two trends: while one group is longing for the integration into modernity at any cost, the other group stands for the preservation of traditional values. Hence, the Baka are in a process of transition. Keywords: Ethnicity, identity, structuralism, constructivism, transition. Introduction After the Cold War and the fall of the Berlin Wall, the world entered into a new era characterised by the triumph of globalisation. -

Ancient Maya: the Rise and Fall of a Rainforest Civilization Arthur Demarest Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521592240 - Ancient Maya: The Rise and Fall of a Rainforest Civilization Arthur Demarest Index More information Index Abaj Takalik (Guatemala) 64, 67, 69, 72, animals 76, 78, 84, 102 association with kings and priests 184, aboriculture 144–145 185 acropoli see epicenters and bird life, rain forests 123–126 agriculture 117–118 and rulers 229 animal husbandry 145 apiculture 145 Classic period 90, 146–147 archaeology effects of the collapse, Petexbatun 254 and chronology 17, 26 operations in relation to the role of elites and cultural evolution 22–23, 26, 27 and rulers 213 history 31 post-Spanish Conquest 290 genesis of scientific archaeology 37–41 Postclassic period, Yucatan 278 multidisciplinary archaeology 41–43 in relation to kingship 206 nineteenth century 34–37 specialization 166 Spanish Conquest 31–33 and trade 150 processual archaeology 23, 26 see also farming practices; gardens; rain settlement pattern archaeology 50, 52 forests architecture 99 Aguateca 230, 251, 252, 259, 261 corbeled vault architecture 90, 94, 95 craft production 164 northern lowlands, Late Classic period destruction 253 235–236 specialist craft production 168 Puuc area, Late Classic period 236 Ajaw complex 16 roof combs 95 ajaws, cult 103 talud-tablero architectural facades alliances, and vassalages 209 (Teotihuacan) 105, 108 Alm´endariz, Ricardo 33 Arroyo de Piedras (western Pet´en)259 alphabet 46, 48 astronomy 201 Alta Vista 79 and astrology 192–193 Altar de Sacrificios (Petexbatun) 38, 49, Atlantis (lost continent) 33, 35 81, 256, -

Sources and Resources/ Fuentes Y Recursos

ST. FRANCIS AND THE AMERICAS/ SAN FRANCISCO Y LAS AMÉRICAS: Sources and Resources/ Fuentes y Recursos Compiled by Gary Francisco Keller 1 Table of Contents Sources and Resources/Fuentes y Recursos .................................................. 6 CONTROLLABLE PRIMARY DIGITAL RESOURCES 6 Multimedia Compilation of Digital and Traditional Resources ........................ 11 PRIMARY RESOURCES 11 Multimedia Digital Resources ..................................................................... 13 AGGREGATORS OF CONTROLLABLE DIGITAL RESOURCES 13 ARCHIVES WORLDWIDE 13 Controllable Primary Digital Resources 15 European 15 Mexicano (Nahuatl) Related 16 Codices 16 Devotional Materials 20 Legal Documents 20 Maps 21 Various 22 Maya Related 22 Codices 22 Miscellanies 23 Mixtec Related 23 Otomi Related 24 Zapotec Related 24 Other Mesoamerican 24 Latin American, Colonial (EUROPEAN LANGUAGES) 25 PRIMARY RESOURCES IN PRINTED FORM 25 European 25 Colonial Latin American (GENERAL) 26 Codices 26 2 Historical Documents 26 Various 37 Mexicano (Nahautl) Related 38 Codices 38 Lienzo de Tlaxcala 44 Other Lienzos, Mapas, Tiras and Related 45 Linguistic Works 46 Literary Documents 46 Maps 47 Maya Related 48 Mixtec Related 56 Otomí Related 58 (SPREAD OUT NORTH OF MEXICO CITY, ALSO HIDALGO CLOSELY ASSOCIATED WITH THE OTOMÍ) Tarasco Related 59 (CLOSELY ASSOCIATED WITH MICHOACÁN. CAPITAL: TZINTZUNRZAN, LANGUAGE: PURÉPECHA) Zapotec Related 61 Other Mesoamerican 61 Latin American, Colonial (EUROPEAN LANGUAGES) 61 FRANCISCAN AND GENERAL CHRISTIAN DISCOURSE IN NATIVE -

The Significance of Copper Bells in the Maya Lowlands from Their

The significance of Copper bells in the Maya Lowlands On the cover: 12 bells unearthed at Lamanai, including complete, flattened and miscast specimens. From Simmons and Shugar 2013: 141 The significance of Copper bells in the Maya Lowlands - from their appearance in the Late Terminal Classic period to the current day - Arthur Heimann Master Thesis S2468077 Prof. Dr. P.A.I.H. Degryse Archaeology of the Americas Leiden University, Faculty of Archaeology (1084TCTY-F-1920ARCH) Leiden, 16/12/2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 5 1.1. Subject of The Thesis ................................................................................................................... 6 1.2. Research Question........................................................................................................................ 7 2. MAYA SOCIETY ........................................................................................................................... 10 2.1. Maya Geography.......................................................................................................................... 10 2.2. Maya Chronology ........................................................................................................................ 13 2.2.1. Preclassic ............................................................................................................................................................. 13 2.2.2. -

Baking Pot Codex Restoration Project, Belize

FAMSI © 2005: Carolyn M. Audet Baking Pot Codex Restoration Project, Belize Research Year: 2003 Culture: Maya Chronology: Late Classic Location: Belize Site: Baking Pot Table of Contents Abstract Resumen Section I Discovery of Tomb 2, Baking Pot, Belize Tomb 2 Section II - Harriet Beaubien Excavation of the Artifacts Goals of Conservation and Technical Analysis Description of the Artifacts Goals of the Project Artifact Conservation Stabilization for Transport List of Components Conservation of Artifact R at SCMRE Technical Study of Paint Flakes Paint Layer Composition Ground Layer Composition Painting Technique and Decorative Scheme Indicators of the Original Substrate(s) Preliminary Interpretation of the Artifacts Object Types Contributions to Technical Studies of Maya Painting Traditions List of Figures Sources Cited Abstract During the 2002 field season a decayed stuccoed artifact was uncovered in a tomb at the site of Baking Pot. Initially, we believed that the painted stucco could be the remains of an ancient Maya codex. After funds were secured, Harriet Beaubien traveled to Belize to recover the material and bring it to the Smithsonian Institute for conservation and analysis. After more than a year of painstaking study Beaubien determined that the artifact was not a codex, but rather a number of smaller artifacts, similar in style and composition to gourds found at Cerén, El Salvador. Resumen Durante la temporada 2002, se encontró un artefacto de estuco en mal estado de preservación en una tumba de Baking Pot. En un principio, pensamos que el estuco pintado podrían ser los restos de un códice maya. Una vez asegurados los fondos necesarios, Harriet Beaubien viajó a Belice para recuperar el material y llevarlo al Instituto de Conservación de la Smithsonian para su conservación y análisis. -

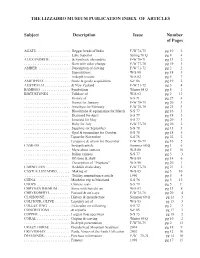

List of Articles

THE LIZZADRO MUSEUM PUBLICATION INDEX OF ARTICLES Subject Description Issue Number of Pages AGATE. .. Beggar beads of India F-W 74-75 pg 10 2 . Lake Superior Spring 70 Q pg 8 4 ALEXANDRITE . & Synthetic alexandrite F-W 70-71 pg 13 2 . Gem with color change F-W 77-78 pg 19 1 AMBER . Description of carving F-W 71-72 pg 2 2 . Superstitions W-S 80 pg 18 5 . in depth treatise W-S 82 pg 5 7 AMETHYST . Stone & geode acquisitions S-F 86 pg 19 2 AUSTRALIA . & New Zealand F-W 71-72 pg 3 4 BAMBOO . Symbolism Winter 68 Q pg 8 1 BIRTHSTONES . Folklore of W-S 93 pg 2 13 . History of S-S 71 pg 27 4 . Garnet for January F-W 78-79 pg 20 3 . Amethyst for February F-W 78-79 pg 22 3 . Bloodstone & aquamarine for March S-S 77 pg 16 3 . Diamond for April S-S 77 pg 18 3 . Emerald for May S-S 77 pg 20 3 . Ruby for July F-W 77-78 pg 20 2 . Sapphire for September S-S 78 pg 15 3 . Opal & tourmaline for October S-S 78 pg 18 5 . Topaz for November S-S 78 pg 22 2 . Turquoise & zircon for December F-W 78-79 pg 16 5 CAMEOS . In-depth article Summer 68 Q pg 1 6 . More about cameos W-S 80 pg 5 10 . Italian cameos S-S 77 pg 3 3 . Of stone & shell W-S 89 pg 14 6 . Description of “Neptune” W-S 90 pg 20 1 CARNELIAN . -

Chwa Nima Ab'aj ( Mixco Viejo)

1 2 Chwa Nima Ab’aj ( Mixco Viejo) “Recordación Florida”, o, “Historia del Reyno de Goathemala”, es una obra escrita por el Capitán Francisco Fuentes y Guzmán en 1690, o sea unos 165 años después de que fuerzas invasoras españolas ocuparan el territorio de la actual Guatemala. A Fuentes y Guzmán se le considera el primer historiador criollo guatemalteco, ya que en esta obra narra lo que se acredita como la primera historia general del país. Por los cargos ocupados: Cronista de Ciudad nombrado por el Rey, Regidor Perpetuo del Ayuntamiento y Alcalde Mayor tuvo acceso a numerosos documentos (muchos desaparecidos) que le permitió hacer esa monumental obra. Hoy día, con la aparición de otros antiguos documentos con narraciones tanto de indígenas, como de españoles y mestizos, algunos de los datos y hechos consignados en la famosa “Recordación Florida” han sido refutados, negados o impugnados, sin que por esos casos se ponga en cuestión la trascendencia de la obra del “Cronista de la Ciudad”. Esta obra es de capital importancia pues en ella se consigna por vez primera la existencia de Mixco, (Chwa Nima Ab’aj) así como los sucesos acaecidos en la batalla que finalizó con su destrucción por parte de los españoles. Sin embargo, a pesar de la autenticidad narrativa de Fuentes y Guzmán sobre la batalla librada para ocupar Mixco, el nombre que le dio a esta inigualable ciudadela ceremonial, así como los datos sobre la etnia indígena que la habitaba y defendió ante la invasión española, los Pokomames, han sido impugnados sobre la base de estudios antropológicos, arqueológicos y documentos indígenas escritos recién terminada la conquista. -

Physical Expression of Sacred Space Among the Ancient Maya

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Sociology & Anthropology Faculty Research Sociology and Anthropology Department 1-2004 Models of Cosmic Order: Physical Expression of Sacred Space Among the Ancient Maya Jennifer P. Mathews Trinity University, [email protected] J. F. Garber Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/socanthro_faculty Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the Sociology Commons Repository Citation Mathews, J. P., & Garber, J. F. (2004). Models of cosmic order: Physical expression of sacred space among the ancient Maya. Ancient Mesoamerica, 15(1), 49-59. doi: 10.1017/S0956536104151031 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology and Anthropology Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology & Anthropology Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ancient Mesoamerica, 15 (2004), 49–59 Copyright © 2004 Cambridge University Press. Printed in the U.S.A. DOI: 10.1017/S0956536104151031 MODELS OF COSMIC ORDER Physical expression of sacred space among the ancient Maya Jennifer P. Mathewsa and James F. Garberb aDepartment of Sociology and Anthropology, Trinity University, One Trinity Place, San Antonio, TX 78212, USA bDepartment of Anthropology, Texas State University, San Marcos, TX 78666, USA Abstract The archaeological record, as well as written texts, oral traditions, and iconographic representations, express the Maya perception of cosmic order, including the concepts of quadripartite division and layered cosmos. The ritual act of portioning and layering created spatial order and was used to organize everything from the heavens to the layout of altars. -

The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: a Multilevel Process Theory1

The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: A Multilevel Process Theory1 Andreas Wimmer University of California, Los Angeles Primordialist and constructivist authors have debated the nature of ethnicity “as such” and therefore failed to explain why its charac- teristics vary so dramatically across cases, displaying different de- grees of social closure, political salience, cultural distinctiveness, and historical stability. The author introduces a multilevel process theory to understand how these characteristics are generated and trans- formed over time. The theory assumes that ethnic boundaries are the outcome of the classificatory struggles and negotiations between actors situated in a social field. Three characteristics of a field—the institutional order, distribution of power, and political networks— determine which actors will adopt which strategy of ethnic boundary making. The author then discusses the conditions under which these negotiations will lead to a shared understanding of the location and meaning of boundaries. The nature of this consensus explains the particular characteristics of an ethnic boundary. A final section iden- tifies endogenous and exogenous mechanisms of change. TOWARD A COMPARATIVE SOCIOLOGY OF ETHNIC BOUNDARIES Beyond Constructivism The comparative study of ethnicity rests firmly on the ground established by Fredrik Barth (1969b) in his well-known introduction to a collection 1 Various versions of this article were presented at UCLA’s Department of Sociology, the Institute for Migration Research and Intercultural Studies of the University of Osnabru¨ ck, Harvard’s Center for European Studies, the Center for Comparative Re- search of Yale University, the Association for the Study of Ethnicity at the London School of Economics, the Center for Ethnicity and Citizenship of the University of Bristol, the Department of Political Science and International Relations of University College Dublin, and the Department of Sociology of the University of Go¨ttingen. -

Eta Y Iota En Guatemala

Evaluación de los efectos e impactos de las depresiones tropicales Eta y Iota en Guatemala México Belice Petén Huehuetenango Guatemala Quiché Alta Verapaz Izabal Baja Verapaz San Marcos Zacapa Quetzaltenango Chiquimula Honduras Guatemala Sololá Suchitepéquez Jutiapa Escuintla El Salvador Nicaragua Gracias por su interés en esta publicación de la CEPAL Publicaciones de la CEPAL Si desea recibir información oportuna sobre nuestros productos editoriales y actividades, le invitamos a registrarse. Podrá definir sus áreas de interés y acceder a nuestros productos en otros formatos. www.cepal.org/es/publications Publicaciones www.cepal.org/apps Evaluación de los efectos e impactos de las depresiones tropicales Eta y Iota en Guatemala Este documento fue coordinado por Omar D. Bello, Oficial de Asuntos Económicos de la Oficina de la Secretaría de la Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL), y Leda Peralta, Oficial de Asuntos Económicos de la Unidad de Comercio Internacional e Industria de la sede subregional de la CEPAL en México, en el marco de las actividades del Programa Ordinario de Cooperación Técnica implementado por la CEPAL. Fue preparado por Álvaro Monett, Asesor Regional en Gestión de Información Geoespacial de la División de Estadísticas de la CEPAL, y Juan Carlos Rivas y Jesús López, Oficiales de Asuntos Económicos de la Unidad de Desarrollo Económico de la sede subregional de la CEPAL en México. Participaron en su elaboración los siguientes consultores de la CEPAL: Raffaella Anilio, Horacio Castellaro, Carlos Espiga, Adrián Flores, Hugo Hernández, Francisco Ibarra, Sebastián Moya, María Eugenia Rodríguez y Santiago Salvador, así como los siguientes funcionarios del Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (BID): Ginés Suárez, Omar Samayoa y Renato Vargas, y los siguientes funcionarios del Banco Mundial: Osmar Velasco, Ivonne Jaimes, Doris Souza, Juan Carlos Cárdenas y Mariano González. -

Adoring Our Wounds: Suicide, Prevention, and the Maya in Yucatán, México

Adoring Our Wounds: Suicide, Prevention, and the Maya in Yucatán, México By Beatriz Mireya Reyes-Cortes A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Stanley Brandes, Chair Professor William F. Hanks Professor Lawrence Cohen Professor William B. Taylor Spring 2011 Adoring our Wounds: Suicide, Prevention, and the Maya in Yucatán, México Copyright 2011 by Beatriz Mireya Reyes-Cortes Abstract Adoring Our Wounds: Suicide, Prevention, and the Maya in Yucatán, México By Beatriz Mireya Reyes-Cortes Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Professor Stanley S. Brandes The first decade of the 21st century has seen a transformation in national and regional Mexican politics and society. In the state of Yucatán, this transformation has taken the shape of a newfound interest in indigenous Maya culture coupled with increasing involvement by the state in public health efforts. Suicide, which in Yucatán more than doubles the national average, has captured the attention of local newspaper media, public health authorities, and the general public; it has become a symbol of indigenous Maya culture due to an often cited association with Ixtab, an ancient Maya ―suicide goddess‖. My thesis investigates suicide as a socially produced cultural artifact. It is a study of how suicide is understood by many social actors and institutions and of how upon a close examination, suicide can be seen as a trope that illuminates the complexity of class, ethnicity, and inequality in Yucatán. In particular, my dissertation –based on extensive ethnographic and archival research in Valladolid and Mérida, Yucatán, México— is a study of both suicide and suicide prevention efforts.