A Mat of Serpents: Aztec Strategies of Control from an Empire in Decline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cobró Los Tributos Y Fungió Tan Sólo Como Un Intermediario En Los Proyectos Del Conquistador

El gobierno de Toluca en los inicios del siglo xvi cobró los tributos y fungió tan sólo como un intermediario en los proyectos del conquistador. Algunos testimonios confrman que Cortés confó “al descendiente de Chimaltecuhtli”, la administración de las tierras que Axayacatl y Moctezuma se habían adjudicado, es decir, aque- llas donde marcaron los contornos de la Villa de Toluca y de sus barrios.42 Ahora bien, Macacoyotzin reinó muy poco tiempo ya que Cortés pronto lo alejó acu- sándolo de idolatría. Al respecto, el testimonio de Francisco de Santiago destaca: “[…] por aver idolatrado y cometido delito con una hija suya lo llevaron a México y quedó en su lugar en la dicha población de Toluca don Pedro Cortés su hijo por manera que […] no fue señor ni cacique en la dicha villa y población y tierras a donde está agora fundada la dicha villa de Toluca el dicho Macacoyotzin cacique de ella sino principal como dicho tiene”. 43 En la época en que fray Juan de Zumárraga fue arzobispo de México, Macacoyotzin habría sido llevado al convento de San Francisco en la capital, donde cumplió años de con- dena. Nada indica que haya regresado a la región de Toluca. Su hijo, don Pedro Cortés indio, sucedió a su padre como gobernador. Lo cierto es que Cortés sacó provecho del alejamiento de Macacoyotzin de México para apresurar la creación de la villa de Toluca. Resumiendo, los testimonios anexados al expediente muestran cómo Cortés logró eli- minar la posible infuencia del señor matlatzinca, no sin haber utilizado sus funciones de gobernador lo mejor que pudo. -

Aztec Mythology

Aztec Mythology One of the main things that must be appreciated about Aztec mythology is that it has both similarities and differences to European polytheistic religions. The idea of what a god was, and how they acted, was not the same between the two cultures. Along with all other native American religions, the Aztec faith developed from the Shamanism brought by the first migrants over the Bering Strait, and developed independently of influences from across the Atlantic (and Pacific). The concept of dualism is one that students of Chinese religions should be aware of; the idea of balance was primary in this belief system. Gods were not entirely good or entirely bad, being complex characters with many different aspects and their own desires and motivations. This is highlighted by the relation between Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca. When the Spanish arrived with their European sensibilities, they were quick to name one good and one evil, identifying Quetzalcoatl with Christ and Tezcatlipoca with Satan during their attempts to integrate the Nahua peoples into Christianity. But to the Aztecs neither god would have been “better” than the other; they are just different and opposing sides of the same duality. Indeed, their identities are rather nebulous, with Quetzalcoatl often being referred to as “White Tezcatlipoca” and Tezcatlipoca as “Black Quetzalcoatl”. The Mexica, as is explained in the history section, came from North of Mexico in a location they named “Aztlan” (from which Europeans developed the term Aztec). During their migration south they were exposed to and assimilated elements of several native religions, including those of the Toltecs, Mayans, and Zapotecs. -

Collision of Civilizations

Collision of Civilizations Spaniards, Aztecs and Incas 1492- The clash begins Only two empires in the New World Cahokia Ecuador Aztec Empire The Aztec State in 1519 • Mexico 1325 Aztecs start to build their capital city, Tenochtitlan. • 1502 Montezuma II becomes ruler, wars against the independent city-states in the Valley of Mexico. The Aztec empire was in a fragile state, stricken with military failures, economic trouble, and social unrest. Montezuma II had attempted to centralize power and maintain the over-extended empire expanded over the Valley of Mexico, and into Central America. It was an extortionist regime, relied on force to extract prisoners, tribute, and food levies from neighboring peoples. As the Aztec state weakened, its rulers and priests continued to demand human sacrifice to feed its gods. In 1519, the Aztec Empire was not only weak within, but despised and feared from without. When hostilities with the Spanish began, the Aztecs had few allies. Cortes • 1485 –Cortes was born in in Medellin, Extremadura, Spain. His parents were of small Spanish nobility. • 1499, when Cortes was 14 he attended the University of Salamanca, at this university he studied law. • 1504 (19) he set sail for what is now the Dominican Republic to try his luck in the New World. • 1511, (26) he joined an army under the command of Spanish soldier named Diego Velázquez and played a part the conquest of Cuba. Velázquez became the governor of Cuba, and Cortes was elected Mayor-Judge of Santiago. • 1519 (34) Cortes expedition enters Mexico. • Aug. 13, 1521 15,000 Aztecs die in Cortes' final all-out attack on the city. -

Hierarchy in the Representation of Death in Pre- and Post-Conquest Aztec Codices

1 Multilingual Discourses Vol. 1.2 Spring 2014 Tanya Ball The Power of Death: Hierarchy in the Representation of Death in Pre- and Post-Conquest Aztec Codices hrough an examination of Aztec death iconography in pre- and post-Conquest codices of the central valley of Mexico T (Borgia, Mendoza, Florentine, and Telleriano-Remensis), this paper will explore how attitudes towards the Aztec afterlife were linked to questions of hierarchical structure, ritual performance and the preservation of Aztec cosmovision. Particular attention will be paid to the representation of mummy bundles, sacrificial debt- payment and god-impersonator (ixiptla) sacrificial rituals. The scholarship of Alfredo López-Austin on Aztec world preservation through sacrifice will serve as a framework in this analysis of Aztec iconography on death. The transformation of pre-Hispanic traditions of representing death will be traced from these pre- to post-Conquest Mexican codices, in light of processes of guided syncretism as defined by Hugo G. Nutini and Diana Taylor’s work on the performative role that codices play in re-activating the past. These practices will help to reflect on the creation of the modern-day Mexican holiday of Día de los Muertos. Introduction An exploration of the representation of death in Mexica (popularly known as Aztec) pre- and post-Conquest Central Mexican codices is fascinating because it may reveal to us the persistence and transformation of Aztec attitudes towards death and the after-life, which in some cases still persist today in the Mexican holiday Día de Tanya Ball 2 los Muertos, or Day of the Dead. This tradition, which hails back to pre-Columbian times, occurs every November 1st and 2nd to coincide with All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ day in the Christian calendar, and honours the spirits of the deceased. -

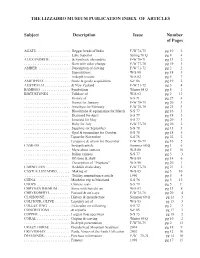

List of Articles

THE LIZZADRO MUSEUM PUBLICATION INDEX OF ARTICLES Subject Description Issue Number of Pages AGATE. .. Beggar beads of India F-W 74-75 pg 10 2 . Lake Superior Spring 70 Q pg 8 4 ALEXANDRITE . & Synthetic alexandrite F-W 70-71 pg 13 2 . Gem with color change F-W 77-78 pg 19 1 AMBER . Description of carving F-W 71-72 pg 2 2 . Superstitions W-S 80 pg 18 5 . in depth treatise W-S 82 pg 5 7 AMETHYST . Stone & geode acquisitions S-F 86 pg 19 2 AUSTRALIA . & New Zealand F-W 71-72 pg 3 4 BAMBOO . Symbolism Winter 68 Q pg 8 1 BIRTHSTONES . Folklore of W-S 93 pg 2 13 . History of S-S 71 pg 27 4 . Garnet for January F-W 78-79 pg 20 3 . Amethyst for February F-W 78-79 pg 22 3 . Bloodstone & aquamarine for March S-S 77 pg 16 3 . Diamond for April S-S 77 pg 18 3 . Emerald for May S-S 77 pg 20 3 . Ruby for July F-W 77-78 pg 20 2 . Sapphire for September S-S 78 pg 15 3 . Opal & tourmaline for October S-S 78 pg 18 5 . Topaz for November S-S 78 pg 22 2 . Turquoise & zircon for December F-W 78-79 pg 16 5 CAMEOS . In-depth article Summer 68 Q pg 1 6 . More about cameos W-S 80 pg 5 10 . Italian cameos S-S 77 pg 3 3 . Of stone & shell W-S 89 pg 14 6 . Description of “Neptune” W-S 90 pg 20 1 CARNELIAN . -

Stear Dissertation COGA Submission 26 May 2015

BEYOND THE FIFTH SUN: NAHUA TELEOLOGIES IN THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES By ©Copyright 2015 Ezekiel G. Stear Submitted to the graduate degree program in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson, Santa Arias ________________________________ Verónica Garibotto ________________________________ Patricia Manning ________________________________ Rocío Cortés ________________________________ Robert C. Schwaller Date Defended: May 6, 2015! ii The Dissertation Committee for Ezekiel G. Stear certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: BEYOND THE FIFTH SUN: NAHUA TELEOLOGIES IN THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES ________________________________ Chairperson, Santa Arias Date approved: May 6, 2015 iii Abstract After the surrender of Mexico-Tenochtitlan to Hernán Cortés and his native allies in 1521, the lived experiences of the Mexicas and other Nahuatl-speaking peoples in the valley of Mexico shifted radically. Indigenous elites during this new colonial period faced the disappearance of their ancestral knowledge, along with the imposition of Christianity and Spanish rule. Through appropriations of linear writing and collaborative intellectual projects, the native population, in particular the noble elite sought to understand their past, interpret their present, and shape their future. Nahua traditions emphasized balanced living. Yet how one could live out that balance in unknown times ahead became a topic of ongoing discussion in Nahua intellectual communities, and a question that resounds in the texts they produced. Writing at the intersections of Nahua studies, literary and cultural history, and critical theory, in this dissertation I investigate how indigenous intellectuals in Mexico-Tenochtitlan envisioned their future as part of their re-evaluations of the past. -

The Toro Historical Review

THE TORO HISTORICAL REVIEW Native Communities in Colonial Mexico Under Spanish Colonial Rule Vannessa Smith THE TORO HISTORICAL REVIEW Prior to World War II and the subsequent social rights movements, historical scholarship on colonial Mexico typically focused on primary sources left behind by Iberians, thus revealing primarily Iberian perspectives. By the 1950s, however, the approach to covering colonial Mexican history changed with the scholarship of Charles Gibson, who integrated Nahuatl cabildo records into his research on Tlaxcala.1 Nevertheless, in his subsequent book The Aztecs under Spanish Rule Gibson went back to predominantly Spanish sources and thus an Iberian lens to his research.2 It was not until the 1970s and 80s that U.S. scholars, under the leadership of James Lockhart, developed a methodology called the New Philology, which focuses on native- language driven research on colonial Mexican history.3 The New Philology has become an important research method in the examination of native communities and the ways in which they changed and adapted to Spanish rule while also holding on to some of their own social and cultural practices and traditions. This historiography focuses on continuities and changes in indigenous communities, particularly the evolution of indigenous socio-political structures and socio-economic relationships under Spanish rule, in three regions of Mexico: Central Mexico, Yucatan, and Oaxaca. Pre-Conquest Community Structure As previously mentioned, Lockhart provided the first scholarship following the New Philology methodology in the United States and applied it to Central Mexico. In his book, The Nahuas After the Conquest, Lockhart lays out the basic structure of Nahua communities in great detail.4 The Nahua, the prominent indigenous group in Central Mexico, organized into communities called altepetl. -

COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT for DISTRIBUTION Figure 0.3

Contents Acknowledgments ix A Brief Note on Usage xiii Introduction: History and Tlaxilacalli 3 Chapter 1: The Rise of Tlaxilacalli, ca. 1272–1454 40 Chapter 2: Acolhua Imperialisms, ca. 1420s–1583 75 Chapter 3: Community and Change in Cuauhtepoztlan Tlaxilacalli, ca. 1544–1575 97 Chapter 4: Tlaxilacalli Religions, 1537–1587 123 COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL Chapter 5: TlaxilacalliNOT FOR Ascendant, DISTRIBUTION 1562–1613 151 Chapter 6: Communities Reborn, 1581–1692 174 Conclusion: Tlaxilacalli and Barrio 203 List of Acronyms Used Frequently in This Book 208 Bibliography 209 Index 247 vii introduction History and Tlaxilacalli This is the story of how poor, everyday central Mexicans built and rebuilt autono- mous communities over the course of four centuries and two empires. It is also the story of how these self-same commoners constructed the unequal bonds of compul- sion and difference that anchored these vigorous and often beloved communities. It is a story about certain face-to-face human networks, called tlaxilacalli in both singular and plural,1 and about how such networks molded the shape of both the Aztec and Spanish rule.2 Despite this influence, however, tlaxilacalli remain ignored, subordinated as they often were to wider political configurations and most often appearing unmarked—that is, noted by proper name only—in the sources. With care, however, COPYRIGHTEDthe deeper stories of tlaxilacalli canMATERIAL be uncovered. This, in turn, lays bare a root-level history of autonomy and colonialism in central Mexico, told through the powerfulNOT and transformative FOR DISTRIBUTION tlaxilacalli. The robustness of tlaxilacalli over thelongue durée casts new and surprising light on the structures of empire in central Mexico, revealing a counterpoint of weakness and fragmentation in the canonical histories of centralizing power in the region. -

The Bilimek Pulque Vessel (From in His Argument for the Tentative Date of 1 Ozomatli, Seler (1902-1923:2:923) Called Atten- Nicholson and Quiñones Keber 1983:No

CHAPTER 9 The BilimekPulqueVessel:Starlore, Calendrics,andCosmologyof LatePostclassicCentralMexico The Bilimek Vessel of the Museum für Völkerkunde in Vienna is a tour de force of Aztec lapidary art (Figure 1). Carved in dark-green phyllite, the vessel is covered with complex iconographic scenes. Eduard Seler (1902, 1902-1923:2:913-952) was the first to interpret its a function and iconographic significance, noting that the imagery concerns the beverage pulque, or octli, the fermented juice of the maguey. In his pioneering analysis, Seler discussed many of the more esoteric aspects of the cult of pulque in ancient highland Mexico. In this study, I address the significance of pulque in Aztec mythology, cosmology, and calendrics and note that the Bilimek Vessel is a powerful period-ending statement pertaining to star gods of the night sky, cosmic battle, and the completion of the Aztec 52-year cycle. The Iconography of the Bilimek Vessel The most prominent element on the Bilimek Vessel is the large head projecting from the side of the vase (Figure 2a). Noting the bone jaw and fringe of malinalli grass hair, Seler (1902-1923:2:916) suggested that the head represents the day sign Malinalli, which for the b Aztec frequently appears as a skeletal head with malinalli hair (Figure 2b). However, because the head is not accompanied by the numeral coefficient required for a completetonalpohualli Figure 2. Comparison of face date, Seler rejected the Malinalli identification. Based on the appearance of the date 8 Flint on front of Bilimek Vessel with Aztec Malinalli sign: (a) face on on the vessel rim, Seler suggested that the face is the day sign Ozomatli, with an inferred Bilimek Vessel, note malinalli tonalpohualli reference to the trecena 1 Ozomatli (1902-1923:2:922-923). -

Anales Mexicanos

A~.\LES. Ml~XICO- AZCAPOTZALCO. 49. ANALES MEXICANOS. México- Azcapotzalco. 1.426-1.589. 11?.ADUCCION de un manuscrito antiguo 1nexicano, que c01ztienza con tnedia hoja rota, y al parecer empieza su contenido desde el año de 1415. En el año de doce conejos (1426) murió Tezozomoc, soberano de Azcapotzalco. Reinó en él sesenta años. Tuvo, segun consta y se sabe positivamente, cuatro hijos. Al primero, llamado Acolnahuacatl, le dió el Señorío y el gobierno de Tlacopan (hoy Tacuba). Al segundo, Cuacuauhpz'tzalmac, el gobierno de Tlatilolco. Al tercero, Ep coatzin, el de Atlacuihuayan (hoy Tacubaya). Al cuarto, Maxtlatzin, el de Coyoacan. Cumplidos nueve años de esta distribucion de reinos y gobiernos, murió Cua wauhpitzahuac, succedíéndole inmediatamente su hijo Tlacateotzin, nieto del an ciano y Señor Tezozomoctli é igualmente de Teociteuhtli, que gobernaba á la vez en Acxotlan, Chalco. Luego que murió Tezozomoctli, en ese mismo afio .Maxtlaton se apoderó del mando y Señorío de Azcapotzalco, viniendo de Coyoacan, en donde reinó diez y seis añ.os. Al llegar á Azcapotzalco manifestó que el objeto de su venida era el de tomar parte en el profundo sentimiento por la muerte de su padre. Mas al visitar el cadáver, inmediatamente se postró á sus pies y tomó posesion del imperio de Azcapotzalco. Gobernando Maxtlaton y andando por sus terrenos las mujeres de Chilnalpopoca, repentinamente mandó recogerlas, y estando reunidas las maltrató y les dijo con voz imponente: "vuestros hombres los mexicanos se andan escondiendo dentro de nues tras sementeras, yo los escarmentaré1 y haré morir á vuestro varon Chímalpopocatl y á toda la raza mexicana.» De esta amenaza dieron cuenta las mujeres á Chimalpo poca, diciéndole: ,, gran Señor nuestro, hemos ido á oir allá en Azcapotzalco la fu nesta y terrible sentencia; dizque la sangre mexicana será exterminada; las aves desde * Este manuscrito se escribió en mexicano, y el Sr. -

Encounter with the Plumed Serpent

Maarten Jansen and Gabina Aurora Pérez Jiménez ENCOUNTENCOUNTEERR withwith thethe Drama and Power in the Heart of Mesoamerica Preface Encounter WITH THE plumed serpent i Mesoamerican Worlds From the Olmecs to the Danzantes GENERAL EDITORS: DAVÍD CARRASCO AND EDUARDO MATOS MOCTEZUMA The Apotheosis of Janaab’ Pakal: Science, History, and Religion at Classic Maya Palenque, GERARDO ALDANA Commoner Ritual and Ideology in Ancient Mesoamerica, NANCY GONLIN AND JON C. LOHSE, EDITORS Eating Landscape: Aztec and European Occupation of Tlalocan, PHILIP P. ARNOLD Empires of Time: Calendars, Clocks, and Cultures, Revised Edition, ANTHONY AVENI Encounter with the Plumed Serpent: Drama and Power in the Heart of Mesoamerica, MAARTEN JANSEN AND GABINA AURORA PÉREZ JIMÉNEZ In the Realm of Nachan Kan: Postclassic Maya Archaeology at Laguna de On, Belize, MARILYN A. MASSON Life and Death in the Templo Mayor, EDUARDO MATOS MOCTEZUMA The Madrid Codex: New Approaches to Understanding an Ancient Maya Manuscript, GABRIELLE VAIL AND ANTHONY AVENI, EDITORS Mesoamerican Ritual Economy: Archaeological and Ethnological Perspectives, E. CHRISTIAN WELLS AND KARLA L. DAVIS-SALAZAR, EDITORS Mesoamerica’s Classic Heritage: Teotihuacan to the Aztecs, DAVÍD CARRASCO, LINDSAY JONES, AND SCOTT SESSIONS Mockeries and Metamorphoses of an Aztec God: Tezcatlipoca, “Lord of the Smoking Mirror,” GUILHEM OLIVIER, TRANSLATED BY MICHEL BESSON Rabinal Achi: A Fifteenth-Century Maya Dynastic Drama, ALAIN BRETON, EDITOR; TRANSLATED BY TERESA LAVENDER FAGAN AND ROBERT SCHNEIDER Representing Aztec Ritual: Performance, Text, and Image in the Work of Sahagún, ELOISE QUIÑONES KEBER, EDITOR The Social Experience of Childhood in Mesoamerica, TRACI ARDREN AND SCOTT R. HUTSON, EDITORS Stone Houses and Earth Lords: Maya Religion in the Cave Context, KEITH M. -

Aztec Empire

Summary: Egypt and Rome seem to get all the glory of ancient history and civilization, but what was happening in the rest of the world? Was everyone else just fumbling through life, trying to figure out how to put two syllables together? As it turns out, no. Astoundingly large, marvelous civilizations existed all throughout the world; we just rarely hear about them in our Eurocentric history. The Aztecs built a vast empire, one that outpaced, outstaged, and outpopulated the likes of Paris at the time. They were a powerhouse warrior based society with a devout religious following and growing empire. Then Hernan Cortes showed up with 400 soldiers and took them down, as the traditional story tells us. Or was it really that simple? To the victors, goes the history but let’s dig a little deeper and find out what really happened. Did Montezuma's bloody and superstitious Mexica empire crash at the hands of a few brave conquistadors, as Cortes and history often tell us? Or did a cruel and greedy Cortes walk into a brewing feud and capitalize on the situation? Let’s find out on today’s episode of Timesuck. Aztec History and Settlement: DISCLAIMER: Due to repeated attempts at cultural genocide, dates and figures regarding this topic have become extraordinarily difficult to verify. Book burning was such a rampant practice during Spanish missionary work, that the Aztec histories, lore, and documentation was all but entirely destroyed. Pair that with the nearly complete physical genocide that took place, and little is left. The Spanish recorded their own version of events but the politics at play and sheer volume of discrepancies make it clear that much of what was recorded and used as “history” was propaganda, while other texts (harder to access texts) seem more accurate.