The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: a Multilevel Process Theory1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Racism Is a Virus Toolkit

Table of Contents About This Toolkit.............................................................................................................03 Know History, Know Racism: A Brief History of Anti-AANHPI Racism............04 Exclusion and Colonization of AANHPI People.............................................04 AANHPI Panethnicity.............................................................................................07 Racism Resurfaced: COVID-19 and the Rise of Xenophobia...............................08 Continued Trends....................................................................................................08 Testimonies...............................................................................................................09 What Should I Do If I’m a Victim of a Hate Crime?.........................................10 What Should I Do If I Witness a Hate Crime?..................................................12 Navigating Unsteady Waters: Confronting Racism with your Parents..............13 On Institutional and Internalized Anti-Blackness..........................................14 On Institutionalized Violence...............................................................................15 On Protests................................................................................................................15 General Advice for Explaning Anti-Blackness to Family.............................15 Further Resources...................................................................................................15 -

SEMANTIC DEMARCATION of the CONCEPTS of ENDONYM and EXONYM PRISPEVEK K POMENSKI RAZMEJITVI TERMINOV ENDONIM in EKSONIM Drago Kladnik

Acta geographica Slovenica, 49-2, 2009, 393–428 SEMANTIC DEMARCATION OF THE CONCEPTS OF ENDONYM AND EXONYM PRISPEVEK K POMENSKI RAZMEJITVI TERMINOV ENDONIM IN EKSONIM Drago Kladnik BLA@ KOMAC Bovec – Flitsch – Plezzo je mesto na zahodu Slovenije. Bovec – Flitsch – Plezzo is a town in western Slovenia. Drago Kladnik, Semantic Demarcation of the Concepts of Endonym and Exonym Semantic Demarcation of the Concepts of Endonym and Exonym DOI: 10.3986/AGS49206 UDC: 81'373.21 COBISS: 1.01 ABSTRACT: This article discusses the delicate relationships when demarcating the concepts of endonym and exonym. In addition to problems connected with the study of transnational names (i.e., names of geographical features extending across the territory of several countries), there are also problems in eth- nically mixed areas. These are examined in greater detail in the case of place names in Slovenia and neighboring countries. On the one hand, this raises the question of the nature of endonyms on the territory of Slovenia in the languages of officially recognized minorities and their respective linguistic communities, and their relationship to exonyms in the languages of neighboring countries. On the other hand, it also raises the issue of Slovenian exonyms for place names in neighboring countries and their relationship to the nature of Slovenian endonyms on their territories. At a certain point, these dimensions intertwine, and it is there that the demarcation between the concepts of endonym and exonym is most difficult and problematic. KEY WORDS: geography, geographical names, endonym, exonym, exonimization, geography, linguistics, terminology, ethnically mixed areas, Slovenia The article was submitted for publication on May 4, 2009. -

Queer Theory, Ethno/Musicology, and the Disorientation of the Field

Queer Theory, Ethno/Musicology, and the Disorientation of the Field Steven Moon We spend significant time and space in our academic lives positioning ourselves: within the theory of the field, in regard to the institution, within networks of interlocutors, scholars, performers, and so on. We are likewise trained to critique those positions, to identify modes of power in their myriad manifestations, and to work towards more equitable methods and theory. That is, we constantly are subject to attempts of disciplinary orienta- tion, and constantly negotiate forms of re-orientation. Sara Ahmed reminds us that we might ask not only how we are oriented within our discipline, but also about 1) how the discipline itself is oriented, and 2) how orien- tation within sexuality shapes how our bodies extend into space (2006). This space—from disciplinary space, to performance space, to the space of fieldwork and the archive—is a boundless environment cut by the trails of the constant reorientation of those before us. But our options are more than the dichotomy between “be oriented” and “re-orient oneself.” In this essay, I examine the development of the ethno/musicologies’ (queer) theoretical borrowings from anthropology, sociology, and literary/cultural studies in order to historicize the contemporary queer moment both fields are expe- riencing and demonstrate the ways in which it might dis-orient the field. I trace the histories of this queer-ing trend by beginning with early concep- tualizations of the ethno/musicological projects, scientism, and quantita- tive methods. This is in relation to the anthropological method of ethno- cartography in order to understand the historical difficulties in creating a queer qualitative field, as opposed to those based in hermeneutics. -

North American Academic Research Introduction

+ North American Academic Research Journal homepage: http://twasp.info/journal/home Research Between the Forest and the Village: the New Social Forms of the Baka’s Life in Transition Richard Atimniraye Nyelade 1,2* 1This article is an excerpt of my Master thesis in Visual Cultural Studies defended at the University of Tromso in Norway in December 2015 under the supervision of Prof Bjørn Arntsen 2Research Officer, Institute of Agricultural Research for Development, P.O.Box 65 Ngaoundere, Cameroon; PhD student in sociology, University of Shanghai, China *Corresponding author [email protected] Accepted: 29 February , 2020; Online: 07 March, 2020 DOI : https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3700533 Abstract: The Baka are part of hunter-gatherers group of central Africa generally called “pygmies”. They are most often presented as an indigenous, monolithic and marginalised entity. After a fieldwork carried out in Nomedjoh village in South-Easthern Cameroon, audiovisual and qualitative data have been collected. The theoretical framework follows the dichotomy between structuralism and constructivism. While the former considers identity as a sum of artefacts identifiable and transmissible from generation to generation, the latter, notably with Fredrik Barth, defines ethnicity as a heterogeneous and dynamic entity that changes according to the time and space. Beyond this controversy, the data from Nomedjoh reveal that the Baka community is characterised by two trends: while one group is longing for the integration into modernity at any cost, the other group stands for the preservation of traditional values. Hence, the Baka are in a process of transition. Keywords: Ethnicity, identity, structuralism, constructivism, transition. Introduction After the Cold War and the fall of the Berlin Wall, the world entered into a new era characterised by the triumph of globalisation. -

A Silent Crisis in Congo: the Bantu and the Twa in Tanganyika

CONFLICT SPOTLIGHT A Silent Crisis in Congo: The Bantu and the Twa in Tanganyika Prepared by Geoffroy Groleau, Senior Technical Advisor, Governance Technical Unit The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), with 920,000 new Bantus and Twas participating in a displacements related to conflict and violence in 2016, surpassed Syria as community 1 meeting held the country generating the largest new population movements. Those during March 2016 in Kabeke, located displacements were the result of enduring violence in North and South in Manono territory Kivu, but also of rapidly escalating conflicts in the Kasaï and Tanganyika in Tanganyika. The meeting was held provinces that continue unabated. In order to promote a better to nominate a Baraza (or peace understanding of the drivers of the silent and neglected crisis in DRC, this committee), a council of elders Conflict Spotlight focuses on the inter-ethnic conflict between the Bantu composed of seven and the Twa ethnic groups in Tanganyika. This conflict illustrates how representatives from each marginalization of the Twa minority group due to a combination of limited community. access to resources, exclusion from local decision-making and systematic Photo: Sonia Rolley/RFI discrimination, can result in large-scale violence and displacement. Moreover, this document provides actionable recommendations for conflict transformation and resolution. 1 http://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2017/pdfs/2017-GRID-DRC-spotlight.pdf From Harm To Home | Rescue.org CONFLICT SPOTLIGHT ⎯ A Silent Crisis in Congo: The Bantu and the Twa in Tanganyika 2 1. OVERVIEW Since mid-2016, inter-ethnic violence between the Bantu and the Twa ethnic groups has reached an acute phase, and is now affecting five of the six territories in a province of roughly 2.5 million people. -

Ethnicity and Its Issues and Perspectives: a Critical Study

European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine ISSN 2515-8260 Volume 07, Issue 07, 2020 Ethnicity And Its Issues And Perspectives: A Critical Study Sanjay Kumar1, Dr. Gowher Ahmad Naik2 1Research Scholar, Lovely Professional University, Phagwara, Department of English 2Assistant Professor Lovely Professional University, Phagwara, Department of English. Abstract: Ethnicity is a complex phenomenon. It is a highly controversial, disputable, problematic term that does not have any fixed meaning and is used as a less emotive term for a race. Ethnicity is a social construct like race, but the main difference is that race refers to phenotypical differences, whereas ethnicity refers to cultural differences. Ethnicity helps an individual to identify with a larger group, and one’s ethnicity may identify an individual. Too many writers like Max Weber, Michael Brown, Wsevolod Isajiw, etc. have discussed many features to define 'ethnicity.' To explain and outline an apparent meaning for ethnicity, authors like Fredrik Barth, Abner Cohen, Michael Hechter, etc. have postulated different approaches such as primordialism, instrumentalism, materialism and constructivism. Robert E. Park has contributed to the theory of ethnicity by focusing on assimilation theory. Authors like Omi and Vinant have openly opposed this theory and considered the immigrant as the basis of ethnicity. The chief motive of this paper is to discuss the shifting meanings of ethnicity and to depict the purpose behind the divisions based on ethnicity. Keywords: Race, Ethnicity, Classification, Primordialism, Instrumentalism. 1. INTRODUCTION Categorization is part of life. We classify people to gain access to them and to identify them quickly. Without classification, it would be difficult to define and identify worldly objects and human beings. -

The Ethnic Security Dilemma and Ethnic Violence: an Alternative Empirical Model and Its Explanatory Power

Res Publica - Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 17 Issue 1 Article 9 July 2012 The Ethnic Security Dilemma and Ethnic Violence: An Alternative Empirical Model and its Explanatory Power Jiaxing Xu Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/respublica Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Xu, Jiaxing (2012) "The Ethnic Security Dilemma and Ethnic Violence: An Alternative Empirical Model and its Explanatory Power," Res Publica - Journal of Undergraduate Research: Vol. 17 Available at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/respublica/vol17/iss1/9 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by editorial board of Res Publica and the Political Science Department at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. The Ethnic Security Dilemma and Ethnic Violence: An Alternative Empirical Model and its Explanatory Power Abstract Beginning in the 1990s, a trend of using the security dilemma to explain ethnic violence has emerged. However, previous research mainly focuses on individual cases with large-scale violence; whether ethnic security dilemma theory is a sound approach to explain less violent ethnic conflict remains unclear. -

Introduction

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction The Invention of an Ethnic Nationalism he Hindu nationalist movement started to monopolize the front pages of Indian newspapers in the 1990s when the political T party that represented it in the political arena, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP—which translates roughly as Indian People’s Party), rose to power. From 2 seats in the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Indian parliament, the BJP increased its tally to 88 in 1989, 120 in 1991, 161 in 1996—at which time it became the largest party in that assembly—and to 178 in 1998. At that point it was in a position to form a coalition government, an achievement it repeated after the 1999 mid-term elections. For the first time in Indian history, Hindu nationalism had managed to take over power. The BJP and its allies remained in office for five full years, until 2004. The general public discovered Hindu nationalism in operation over these years. But it had of course already been active in Indian politics and society for decades; in fact, this ism is one of the oldest ideological streams in India. It took concrete shape in the 1920s and even harks back to more nascent shapes in the nineteenth century. As a movement, too, Hindu nationalism is heir to a long tradition. Its main incarnation today, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS—or the National Volunteer Corps), was founded in 1925, soon after the first Indian communist party, and before the first Indian socialist party. -

Domestic Ethnic Nationalism and Regional European Transnationalism: a Confluence of Impediments Opposing Turkey’S EU Accession Bid Glen M.E

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville History and Government Faculty Presentations Department of History and Government 4-3-2013 Domestic Ethnic Nationalism and Regional European Transnationalism: A Confluence of Impediments Opposing Turkey’s EU Accession Bid Glen M.E. Duerr Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ history_and_government_presentations Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Duerr, Glen M.E., "Domestic Ethnic Nationalism and Regional European Transnationalism: A Confluence of Impediments Opposing Turkey’s EU Accession Bid" (2013). History and Government Faculty Presentations. 26. https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/history_and_government_presentations/26 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in History and Government Faculty Presentations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Domestic Ethnic Nationalism and Regional European Transnationalism: A Confluence of Impediments Opposing Turkey’s EU Accession Bid Glen M.E. Duerr Assistant Professor of International Studies Cedarville University [email protected] Paper prepared for the International Studies Association (ISA) conference in San Francisco, California, April 2-5, 2013 This paper constitutes a preliminary -

Millennials' National and Global Identities As Drivers of Materialism and Consumer Ethnocentrism Mario V

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity School of Business Faculty Research School of Business 2019 Millennials' National and Global Identities as Drivers of Materialism and Consumer Ethnocentrism Mario V. González Fuentes Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/busadmin_faculty Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons Repository Citation Gonzales-Fuentes, M.V. (2019) Millennials' national and global identities as drivers of materialism and consumer ethnocentrism. Journal of Social Psychology, 159(2), 170-189. doi:10.1080/00224545.2019.1570904 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Business at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Business Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gonzalez-Fuentes, M. Millennials’ Consumer Identities 1 MILLENNIALS’ NATIONAL AND GLOBAL IDENTITIES AS DRIVERS OF MATERIALISM AND CONSUMER ETHNOCENTRISM Mario V. Gonzalez-Fuentes, Trinity University. Abstract A major effect of globalization is one that occurs on the self-concept. This is especially the case for young consumers and particularly for millennials. Despite this cohort’s idiosyncrasies, little attention has been paid to the study of their consumer identities, an important aspect of self-concept. The current research addresses this gap by examining the way millennial consumers’ global and national identities help explain two attitudinal outcomes associated with globalization: materialism and consumer ethnocentrism. Data were collected from millennials in two distinct socio-cultural contexts. A key finding suggests that distinct contexts (i.e., collectivist and ethnically homogeneous vs. -

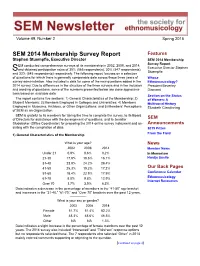

SEM 2014 Membership Survey Report Features Stephen Stuempfle, Executive Director SEM 2014 Membership

Volume 49, Number 2 Spring 2015 SEM 2014 Membership Survey Report Features Stephen Stuempfle, Executive Director SEM 2014 Membership EM conducted comprehensive surveys of its membership in 2002, 2008, and 2014, Survey Report Executive Director Stephen and obtained participation rates of 35% (565 respondents), 30% (547 respondents), S Stuempfle and 32% (545 respondents) respectively. The following report focuses on a selection of questions for which there is generally comparable data across these three years of Whose survey administration. Also included is data for some of the new questions added in the Ethnomusicology? 2014 survey. Due to differences in the structure of the three surveys and in the inclusion President Beverley and wording of questions, some of the numbers presented below are close approxima- Diamond tions based on available data. Section on the Status The report contains five sections: 1) General Characteristics of the Membership; 2) of Women: A Student Members; 3) Members Employed in Colleges and Universities; 4) Members Multivocal History Employed in Museums, Archives, or Other Organizations; and 5) Members’ Perceptions Elizabeth Clendinning of SEM as an Organization. SEM is grateful to its members for taking the time to complete the survey, to its Board of Directors for assistance with the development of questions, and to Jennifer SEM Studebaker (Office Coordinator) for preparing the 2014 online survey instrument and as- Announcements sisting with the compilation of data. 2015 Prizes From the Field 1) General Characteristics of the Membership What is your age? News 2002 2008 2014 Member News Under 21 0.9% 0.6% 0.2% In Memoriam 21-30 17.9% 19.6% 16.1% Hardja Susilo 31-40 23.9% 24.2% 29.4% 41-50 25.3% 19.2% 17.2% Our Back Pages 51-60 18.4% 22.9% 17.9% Conference Calendar 61-70 8.0% 9.8% 12.9% Ethnomusicology Internet Resources Over 70 3.7% 3.9% 6.3% Data indicates a decrease in the percentage of members in the “41-50” age bracket and increases in the “31-40,” “61-70,” and “Over 70” brackets over the past 12 years. -

Conceptual and Methodological Issues in the Use of Race As a Variable: Policy Implications

Conceptual and Methodological Issues in the Use of Race as a Variable: Policy Implications DORIS Y. WILKINSON and GARY KING University of Kentucky; Westat, Inc. he classification of populations into discrete categories based on phenotypic or genotypic criteria is an accepted Tpractice in the physical and social sciences. In attempting to explain diverse physical characteristics and sociogeographical experiences among populations, the term “ race** has been employed for taxonomic purposes. In most scientific research, however, controversy and confusion have surrounded its use (Fortney 1977). For many scientists such as biologists, geneticists, and physical anthropologists, definitions have consisted primarily o f biological subject matter (e.g., gene pools, blood type, skin color). Social scientists, in contrast, have used the term to refer to behavioral practices (e .g ., cultural patterns, language), social factors (e.g., stratification, income status, discrimination) as well as phenotypic characteristics (e.g. hair texture, skin color, facial features). Yet, neither the biological nor sociological approach to racial classification is devoid o f serious theoretical and methodological shortcomings. Depending on the contextual application, the classification, definition, and recording o f data by race have important implications for health research and health policy. The social science translation has involved considerable complexity and varied theoretical and empirical emphases. Although the concept permeates social and behavioral science as well as epidemiologic research, its meaning is rarely specific or precise with respect to its components and the possible consequences of defining it in a particular way. The Milbank Quarterly, Vol. 65, Suppl. 1, 1987 © 1987 Milbank Memorial Fund . 56 The Use of Race as a 'Variable 57 Moreover, in examining human genetics and the racial proclivity for certain diseases, it is recognized that races are highly heterogeneous categories (McKusick 1969).