Queer Theory, Ethno/Musicology, and the Disorientation of the Field

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SEM 2014 Membership Survey Report Features Stephen Stuempfle, Executive Director SEM 2014 Membership

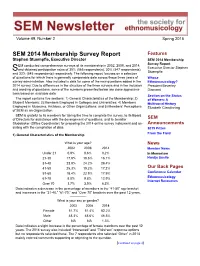

Volume 49, Number 2 Spring 2015 SEM 2014 Membership Survey Report Features Stephen Stuempfle, Executive Director SEM 2014 Membership EM conducted comprehensive surveys of its membership in 2002, 2008, and 2014, Survey Report Executive Director Stephen and obtained participation rates of 35% (565 respondents), 30% (547 respondents), S Stuempfle and 32% (545 respondents) respectively. The following report focuses on a selection of questions for which there is generally comparable data across these three years of Whose survey administration. Also included is data for some of the new questions added in the Ethnomusicology? 2014 survey. Due to differences in the structure of the three surveys and in the inclusion President Beverley and wording of questions, some of the numbers presented below are close approxima- Diamond tions based on available data. Section on the Status The report contains five sections: 1) General Characteristics of the Membership; 2) of Women: A Student Members; 3) Members Employed in Colleges and Universities; 4) Members Multivocal History Employed in Museums, Archives, or Other Organizations; and 5) Members’ Perceptions Elizabeth Clendinning of SEM as an Organization. SEM is grateful to its members for taking the time to complete the survey, to its Board of Directors for assistance with the development of questions, and to Jennifer SEM Studebaker (Office Coordinator) for preparing the 2014 online survey instrument and as- Announcements sisting with the compilation of data. 2015 Prizes From the Field 1) General Characteristics of the Membership What is your age? News 2002 2008 2014 Member News Under 21 0.9% 0.6% 0.2% In Memoriam 21-30 17.9% 19.6% 16.1% Hardja Susilo 31-40 23.9% 24.2% 29.4% 41-50 25.3% 19.2% 17.2% Our Back Pages 51-60 18.4% 22.9% 17.9% Conference Calendar 61-70 8.0% 9.8% 12.9% Ethnomusicology Internet Resources Over 70 3.7% 3.9% 6.3% Data indicates a decrease in the percentage of members in the “41-50” age bracket and increases in the “31-40,” “61-70,” and “Over 70” brackets over the past 12 years. -

Filipino Americans and Polyculturalism in Seattle, Wa

FILIPINO AMERICANS AND POLYCULTURALISM IN SEATTLE, WA THROUGH HIP HOP AND SPOKEN WORD By STEPHEN ALAN BISCHOFF A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN AMERICAN STUDIES WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Department of American Studies DECEMBER 2008 To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the thesis of STEPHEN ALAN BISCHOFF find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. _____________________________________ Chair, Dr. John Streamas _____________________________________ Dr. Rory Ong _____________________________________ Dr. T.V. Reed ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Since I joined the American Studies Graduate Program, there has been a host of faculty that has really helped me to learn what it takes to be in this field. The one professor that has really guided my development has been Dr. John Streamas. By connecting me to different resources and his challenging the confines of higher education so that it can improve, he has been an inspiration to finish this work. It is also important that I mention the help that other faculty members have given me. I appreciate the assistance I received anytime that I needed it from Dr. T.V. Reed and Dr. Rory Ong. A person that has kept me on point with deadlines and requirements has been Jean Wiegand with the American Studies Department. She gave many reminders and explained answers to my questions often more than once. Debbie Brudie and Rose Smetana assisted me as well in times of need in the Comparative Ethnic Studies office. My cohort over the years in the American Studies program have developed my thinking and inspired me with their own insight and work. -

The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: a Multilevel Process Theory1

The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: A Multilevel Process Theory1 Andreas Wimmer University of California, Los Angeles Primordialist and constructivist authors have debated the nature of ethnicity “as such” and therefore failed to explain why its charac- teristics vary so dramatically across cases, displaying different de- grees of social closure, political salience, cultural distinctiveness, and historical stability. The author introduces a multilevel process theory to understand how these characteristics are generated and trans- formed over time. The theory assumes that ethnic boundaries are the outcome of the classificatory struggles and negotiations between actors situated in a social field. Three characteristics of a field—the institutional order, distribution of power, and political networks— determine which actors will adopt which strategy of ethnic boundary making. The author then discusses the conditions under which these negotiations will lead to a shared understanding of the location and meaning of boundaries. The nature of this consensus explains the particular characteristics of an ethnic boundary. A final section iden- tifies endogenous and exogenous mechanisms of change. TOWARD A COMPARATIVE SOCIOLOGY OF ETHNIC BOUNDARIES Beyond Constructivism The comparative study of ethnicity rests firmly on the ground established by Fredrik Barth (1969b) in his well-known introduction to a collection 1 Various versions of this article were presented at UCLA’s Department of Sociology, the Institute for Migration Research and Intercultural Studies of the University of Osnabru¨ ck, Harvard’s Center for European Studies, the Center for Comparative Re- search of Yale University, the Association for the Study of Ethnicity at the London School of Economics, the Center for Ethnicity and Citizenship of the University of Bristol, the Department of Political Science and International Relations of University College Dublin, and the Department of Sociology of the University of Go¨ttingen. -

AS-3438-20/AA Recommended Core Competencies for Ethnic Studies

ACADEMIC SENATE OF THE CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY AS-3438-20/AA September 17-18, 2020 RECOMMENDED CORE COMPETENCIES FOR ETHNIC STUDIES: RESPONSE TO CALIFORNIA EDUCATION CODE 89032C RESOLVED: That the ASCSU acknowledge that the California Education Code 89032c requires “The California State University shall collaborate with the California State University Council on Ethnic Studies and the Academic Senate of the California State University to develop core competencies* to be achieved by students who complete an ethnic studies course…”, and be it further RESOLVED: That the ASCSU recommend the adoption of the following five core ethnic studies competencies iteratively developed by the CSU Council on Ethnic Studies and the ASCSU: • analyze and articulate concepts of ethnic studies, including but not limited to race and ethnicity, racialization, equity, ethno-centrism, eurocentrism, white supremacy, self-determination, liberation, decolonization and anti-racism. • apply theory to describe critical events in the histories, cultures, and intellectual traditions, with special focus on the lived- experiences and social struggles of one or more of the following four historically defined racialized core groups: Native Americans, African Americans, Latina/o Americans, and/or Asian Americans, and emphasizing agency and group-affirmation. • critically discuss the intersection of race and ethnicity with other forms of difference affected by hierarchy and oppression, such as class, gender, sexuality, religion, spirituality, national origin, immigration status, ability, and/or age. • describe how struggle, resistance, social justice, solidarity, and liberation as experienced by communities of color are relevant to current issues. • demonstrate active engagement with anti-racist issues, practices and movements to build a diverse, just, and equitable society beyond the classroom. -

Ethnic Studies Review (ESR) Is the Journal of the National Association for Ethnic Studies (NAES)

The National Association for Ethnic Studies Ethnic Studies Review (ESR) is the journal of the National Association for Ethnic Studies (NAES). ESR is a multi-disciplinary international journal devoted to the study of ethnicity, ethnic groups and their cultures, and intergroup relations. NAES has as its basic purpose the promotion of activities and scholarship in the field of Ethnic Studies. The Association is open to any person or institution and serves as a forum for its members in promoting research, study, and curriculum as well as producing publications of interest in the field. NAES sponsors an annual spring conference. General Editor: Faythe E. Turner, Greenfield Community College Book Review Editor: Jonathan A. Majak, University of Wisconsin-Lacrosse Editorial Advisory Board Edna Acosta-Belen Rhett S. Jones University at Albany, SUNY Brown University Jorge A. Bustamante Paul Lauter El Colegio de la Frontera Norte (Mexico) Trinity College Duane W. Champagne Robert L. Perry University of California, Los Angeles Eastern Michigan University Laura Coltelli Otis L. Scott Universita de Pisa (Italy) California State University Sacramento Russell Endo Alan J. Spector University of Colorado Purdue University, Calumet David M. Gradwohl K. Victor Ujimoto Iowa State University University of Guelph (Canada) Maria Herrera-Sobek John C. Walter University of California, Irvine University of Washington Evelyn Hu-DeHart Bernard Young University of Colorado, Boulder Arizona State University Designed by Eileen Claveloux Ethnic Studies Review (ESR) is published by the National Associaton for Ethnic Studies for its individual members and subscribing libraries and institutions. NAES is a member of the Council of Editors of Learned Journals. -

The Importance of Collecting Data and Doing Social Scientific Research on Race ABOUT the AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

STATEMENT OF THE AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION ON The Importance of Collecting Data and Doing Social Scientific Research on Race ABOUT THE AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION The American Sociological Association (ASA), founded in 1905, is a non-profit membership association dedicated to serving sociologists in their work, advancing sociology as a scientific discipline and profession, and promoting the contributions and use of sociology to society. As the national organization for 13,000 sociologists, the ASA is well positioned to provide a unique set of benefits to its members and to promote the vitality, visibility, and diversity of the discipline. Working at the national and international levels, the Association aims to articulate policy and implement programs likely to have the broadest possible impact for sociology now and in the future. William T. Bielby President Barbara F. Reskin Past-President Michael Burawoy President-Elect Sally T. Hillsman Executive Officer Cite publication as: American Sociological Association. 2003. The Importance of Collecting Data and Doing Social Scientific Research on Race. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association. For Information: American Sociological Association 1307 New York Avenue NW, Suite 700 Washington, DC 20005-4701 Telephone: (202) 383-9005 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.asanet.org Copyright © 2003 by the American Sociological Association The Importance of Collecting Data and Doing Social Scientific Research on Race The question of whether to collect statistics that allow the comparison of differences among racial and ethnic groups in the census, public surveys, and administrative databases is not an abstract one. Some scholarly and civic leaders believe that measuring these differences promotes social divisions and fuels a mistaken perception that race is a biological concept. -

Ethnicity, Multiculturalism and the Problem of Culture

Ethnicity, Multiculturalism and the Problem of Culture Aleksandra Ålund The self-archived postprint version of this journal article is available at Linköping University Institutional Repository (DiVA): http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-45213 N.B.: When citing this work, cite the original publication. This is an electronic version of an article published in: Ålund, A., (1999), Ethnicity, Multiculturalism and the Problem of Culture, European Societies, 1(1), 105-116. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.1999.10749927 Original publication available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.1999.10749927 Copyright: Taylor & Francis (Routledge) (SSH Titles - no Open Select) http://www.routledge.com/ ETHNICITY, MULTICULTURALISM AND THE PROBLEM OF CULTURE Aleksandra Alund Universityof UmeA, Sweden Abstract: This articlediscusses the complex meaning of ethnicity and identity in the multicultural society of today with reference to Swedish society. Sweden, a pronouncedly multiethnic society, is today undergoing division along ethnic lines. Social inequalities tend to be understood in terms of cultural difference. This development seems to be characteristic of most European countries. Culture is usually connected with ethnicity and race and understood as pure, as an 'essence', as related to some original and eternal ethnic core. In this way importantaspects of cultural dynamic in multicultural societya re leftunobserved. What is usually not recognized are cultural crossings and the emergence of composite identities. Within the framework of multicultural society new cultures, identities and ethnicities are created. Departing from some general features of the dominant discourse on ethnicity, its historical roots and its relations to culture and multiculturalism, I discuss problems of cultural essentialism. -

Ethnic Studies Minor Update Proposal Submitted to the Academic Senate

Ethnic Studies Minor Update Proposal submitted to the Academic Senate of Westmont College By Dinora Cardoso, Jason Cha, Kya Mangrum, Felicia Song, Meredith Whitnah, and Sameer Yadav March 19, 2020 Proposal Summary and Rationale We propose an update to the Ethnic Studies Minor as it is currently listed in the College Catalog. Our aim is to better reflect our current course listings, reinvigorate attention to scholarly work around race and ethnicity, and provide institutional support and faculty expertise for campus conversations concerning race and ethnicity. We propose to keep the existing structure of the Minor, but to update the elective offerings and provide an institutional home for the Minor. We also request additional institutional support to allow the Minor to thrive as a vibrant intellectual community within the College that will prepare students to engage with issues of diversity and equity with greater depth and breadth of knowledge. In addition to better serving our current students, we also anticipate that the Ethnic Studies Minor can become an attractive feature of our college curriculum as the changing demographic trends for incoming students will bring in more students, especially students of color, who may particularly be interested in pursuing this minor. We see this Minor as essential to Westmont’s mission as a Christian liberal arts institution that seeks to prepare our students faithfully to engage and to lead in the pluralistic environment that is our contemporary world. Fundamentally interdisciplinary and concerned with issues of both historical and contemporary significance, the Ethnic Studies Minor provides needed institutional space and support for intellectual inquiry around complex and pressing issues faced both by American society generally and American Christianity specifically. -

Race and Ethnicity and Latin America's United Nations Millennium Development Goals

Race and Ethnicity and Latin America’s United Nations Millennium Development Goals Edward E. Telles CCPR‐048‐07 December 2007 California Center for Population Research On-Line Working Paper Series This article was downloaded by:[CDL Journals Account] On: 11 September 2007 Access Details: [subscription number 780222585] Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Latin American and Caribbean Ethnic Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t724921261 Race and Ethnicity and Latin America's United Nations Millennium Development Goals Online Publication Date: 01 October 2007 To cite this Article: Telles, Edward E. (2007) 'Race and Ethnicity and Latin America's United Nations Millennium Development Goals', Latin American and Caribbean Ethnic Studies, 2:2, 185 - 200 To link to this article: DOI: 10.1080/17442220701489571 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17442220701489571 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article maybe used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

High School ELA: ETHNIC STUDIES FRAMEWORK

SEATTLE PUBLIC SCHOOLS High School ELA: ETHNIC STUDIES FRAMEWORK THEMES Origins, Identity, and Agency Power and Oppression Resistance and Liberation Reflection and Action Definition of theme: Definition of theme: Definition of theme: Definition of theme: The theme of identity, as defined by Power and oppression, as defined The history of resistance and Student action, as defined by ethnic ethnic studies, involves looking at by ethnic studies, is: looking at who liberation, as defined by ethnic studies, is fostering a sense of the ways in which our identities and creates the master narrative and studies, is the history of resisting advocacy, empowerment, and sense of belonging affect our how that impacts the lived oppression as carried out by the action in the students that creates worldviews and the choices we experiences of different groups; the oppressed groups themselves. This internal motivation to be a make; at how our identities affect understanding that laws & policies theme directly challenges the “White changemaker. Students will believe the ways we are perceived, and how are not objective; the forces that Savior” narrative. How individuals they can change their current we view ourselves as members of a create a system of white supremacy. who are part of oppressed groups experiences and the experiences of community with distinct cultures and find empowerment and claim people in their community, and feel mores. ownership over their own a sense of accountability to do so. experience. Students understand that a lack of action equates to maintaining the status quo. Learning Targets: Learning Targets: Learning Targets: Learning Targets: ● Students will be able to ● Students can determine who ● Students will recognize ● Students understand that identify their own culture and has power, who doesn’t, and factors and conditions that engaging in social justice analyze how their cultural why, and the implications of motivated people to resist requires humbleness, identities inform their that. -

Ethnic Studies (ETHN) 1

Ethnic Studies (ETHN) 1 ETHN 2013 (3) Critical Issues in Native North America ETHNIC STUDIES (ETHN) Explores a series of issues including regulations of population, land and resource holdings, water rights, education, religious freedom, military Courses obligations, the sociopolitical role of men and women, self-governance, and legal standing as these pertain to American Indian life. ETHN 1022 (3) Introduction to Africana Studies Additional Information: Arts Sci Core Curr: Human Diversity Overview of Africana studies as a field of investigation, its origins and Arts Sci Core Curr: United States Context history. Arts Sci Gen Ed: Diversity-U.S. Perspective Additional Information: Arts Sci Core Curr: Human Diversity Arts Sci Gen Ed: Distribution-Social Sciences Arts Sci Gen Ed: Distribution-Social Sciences Arts Sci Gen Ed: Distribution-Arts Humanities Arts Sci Gen Ed: Distribution-Arts Humanities Departmental Category: American Indian Studies Arts Sci Gen Ed: Diversity-Global Perspective Departmental Category: Africana Studies ETHN 2014 (3) Themes in American Culture 2 Enables students to explore various themes in post-1865 American ETHN 1023 (3) Introduction to Native American and Indigenous Studies culture. Examines these themes, which vary each year, in their social Introduces critical terms, issues, and questions that inform the discipline context. of American Indian Studies. Examines "historical silences" and highlights Additional Information: Arts Sci Core Curr: United States Context how American Indian scholars, poets, and filmmakers use their work Arts Sci Gen Ed: Distribution-Social Sciences to address/redress historical subjects, and represent their Native Departmental Category: American Studies communities. Additional Information: Arts Sci Core Curr: Human Diversity ETHN 2044 (3) Crime and Society Arts Sci Gen Ed: Distribution-Arts Humanities Explores issues related to crime, the criminal justice system, and crime- Arts Sci Gen Ed: Distribution-Social Sciences related public policy. -

Rwanda, Burundi, and Their "Ethnic" Conflicts

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by VCU Scholars Compass Ethnic Studies Review Volume 23 Rwanda, Burundi, and Their "Ethnic" Conflicts Stephen B. Isabirye and Kooros M. Mahmoudi NorthernArizona University. This paper demonstrably dispels the assumption that ethnic conflict in Rwanda and Burundi is a chronic endemic phenomenon. It emphasizes the consolida tion of the caste system during the colonial era, intra regional disparities within the two communities, high population densities, very weak economic bases, poverty, and international interference as some of the cardinal dynamics behind the current deadly con tentions within the two states. An analysis behind the genocidal tendencies in the two countries is well illus trated, with special emphasis on the Rwandese tragedy of 1994 as well as its parallels and diver gences with the Nazi Holocaust. The reason for writing this paper was inspired by a ques tion in the African HistoryAffa irs Paper at the Advanced School Certificate level by the now defunct East African Examinations Council in 1976, which asked why Rwanda and Burundi had frequently fallen prey to "tribal" wars. It is quite obvious that the situation in Rwanda and Burundi in 1976 was by any stretch of imagination "more tame" than the one in 1996. Nevertheless this examination question of 1976 was timely in that by that year Rwanda had experienced its first fully-fledged post colo- 62 lsabirye/Mahmoudi-Conflicts nial military coup that had taken place in 1973, while Burundi had undergone its first mass scale pogroms directed against the majority-Hutu population, which had left up to 250,000 of them dead in 1972.