Toward an Ethnic Studies Pedagogy: Implications for K-12 Schools from the Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(NAME) Conference

30th Annual NAME Conference • 7-11 October 2020 2020 Decolonizing Minds: Forging a New Future through Conference Co-Sponsors Multicultural Education Join us for the 30th NAME conference in this dynamic city with a bold vision of the future. Conference Co-Sponsors: Home to the Southern Poverty Law Center, the Teaching Tolerance • Tennessee Tech • Tucson Unified School District Rosa Parks Museum and the Equal Justice Teachers College Press • Taylor & Francis • Western Ed Equity Assistance Center Initiative's National Memorial for Peace and Justice. NAME CONFERENCE at a GLANCE (CAAG) Wed., Nov. 6 Thur., Nov. 7 Fri., Nov. 8 Sat. , Nov. 9 Sun., Nov. 10 7am-6pm 7:30am-6:30pm 7:30am-5pm 7:30am-12noon 9am-11am Registration Registration Registration Registration Sankofa Sunday 7:30a-5pm 8-8:45am 8-8:45am 8-8:45am Special Border Visit NAME Board meeting Regional meetings Chapter meetings w/continental breakfast w/lcontinental breakfast w/lite continent 11am-6pm 9-9:50 am Special Title IX 9-10:15am 9-10:15am GENERAL Coordinator Training GENERAL GENERAL SESSION — Intensive Institute SESSION — SESSION — Special local panel JEREMY GARCIA MANDY MANNING 12pm-6pm Facilitator - Raul Aguirre 10-10:50am Bill Howe Institute 10:30-11:20am* 10:30-11:20am 11am-11:50pm on Developing a 11:30am-12:20pm** 11:30am-12:20pm breakout sessions MCE Curriculum breakout sessions breakout sessions Marketplace Writing for roundtables Marketplace posters Publication posters posters MC Film Festival Institute MC Film Festival MC Film Festival Conversations… Conversations With… -

Queer Theory, Ethno/Musicology, and the Disorientation of the Field

Queer Theory, Ethno/Musicology, and the Disorientation of the Field Steven Moon We spend significant time and space in our academic lives positioning ourselves: within the theory of the field, in regard to the institution, within networks of interlocutors, scholars, performers, and so on. We are likewise trained to critique those positions, to identify modes of power in their myriad manifestations, and to work towards more equitable methods and theory. That is, we constantly are subject to attempts of disciplinary orienta- tion, and constantly negotiate forms of re-orientation. Sara Ahmed reminds us that we might ask not only how we are oriented within our discipline, but also about 1) how the discipline itself is oriented, and 2) how orien- tation within sexuality shapes how our bodies extend into space (2006). This space—from disciplinary space, to performance space, to the space of fieldwork and the archive—is a boundless environment cut by the trails of the constant reorientation of those before us. But our options are more than the dichotomy between “be oriented” and “re-orient oneself.” In this essay, I examine the development of the ethno/musicologies’ (queer) theoretical borrowings from anthropology, sociology, and literary/cultural studies in order to historicize the contemporary queer moment both fields are expe- riencing and demonstrate the ways in which it might dis-orient the field. I trace the histories of this queer-ing trend by beginning with early concep- tualizations of the ethno/musicological projects, scientism, and quantita- tive methods. This is in relation to the anthropological method of ethno- cartography in order to understand the historical difficulties in creating a queer qualitative field, as opposed to those based in hermeneutics. -

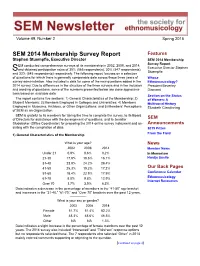

SEM 2014 Membership Survey Report Features Stephen Stuempfle, Executive Director SEM 2014 Membership

Volume 49, Number 2 Spring 2015 SEM 2014 Membership Survey Report Features Stephen Stuempfle, Executive Director SEM 2014 Membership EM conducted comprehensive surveys of its membership in 2002, 2008, and 2014, Survey Report Executive Director Stephen and obtained participation rates of 35% (565 respondents), 30% (547 respondents), S Stuempfle and 32% (545 respondents) respectively. The following report focuses on a selection of questions for which there is generally comparable data across these three years of Whose survey administration. Also included is data for some of the new questions added in the Ethnomusicology? 2014 survey. Due to differences in the structure of the three surveys and in the inclusion President Beverley and wording of questions, some of the numbers presented below are close approxima- Diamond tions based on available data. Section on the Status The report contains five sections: 1) General Characteristics of the Membership; 2) of Women: A Student Members; 3) Members Employed in Colleges and Universities; 4) Members Multivocal History Employed in Museums, Archives, or Other Organizations; and 5) Members’ Perceptions Elizabeth Clendinning of SEM as an Organization. SEM is grateful to its members for taking the time to complete the survey, to its Board of Directors for assistance with the development of questions, and to Jennifer SEM Studebaker (Office Coordinator) for preparing the 2014 online survey instrument and as- Announcements sisting with the compilation of data. 2015 Prizes From the Field 1) General Characteristics of the Membership What is your age? News 2002 2008 2014 Member News Under 21 0.9% 0.6% 0.2% In Memoriam 21-30 17.9% 19.6% 16.1% Hardja Susilo 31-40 23.9% 24.2% 29.4% 41-50 25.3% 19.2% 17.2% Our Back Pages 51-60 18.4% 22.9% 17.9% Conference Calendar 61-70 8.0% 9.8% 12.9% Ethnomusicology Internet Resources Over 70 3.7% 3.9% 6.3% Data indicates a decrease in the percentage of members in the “41-50” age bracket and increases in the “31-40,” “61-70,” and “Over 70” brackets over the past 12 years. -

Filipino Americans and Polyculturalism in Seattle, Wa

FILIPINO AMERICANS AND POLYCULTURALISM IN SEATTLE, WA THROUGH HIP HOP AND SPOKEN WORD By STEPHEN ALAN BISCHOFF A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN AMERICAN STUDIES WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Department of American Studies DECEMBER 2008 To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the thesis of STEPHEN ALAN BISCHOFF find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. _____________________________________ Chair, Dr. John Streamas _____________________________________ Dr. Rory Ong _____________________________________ Dr. T.V. Reed ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Since I joined the American Studies Graduate Program, there has been a host of faculty that has really helped me to learn what it takes to be in this field. The one professor that has really guided my development has been Dr. John Streamas. By connecting me to different resources and his challenging the confines of higher education so that it can improve, he has been an inspiration to finish this work. It is also important that I mention the help that other faculty members have given me. I appreciate the assistance I received anytime that I needed it from Dr. T.V. Reed and Dr. Rory Ong. A person that has kept me on point with deadlines and requirements has been Jean Wiegand with the American Studies Department. She gave many reminders and explained answers to my questions often more than once. Debbie Brudie and Rose Smetana assisted me as well in times of need in the Comparative Ethnic Studies office. My cohort over the years in the American Studies program have developed my thinking and inspired me with their own insight and work. -

The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: a Multilevel Process Theory1

The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: A Multilevel Process Theory1 Andreas Wimmer University of California, Los Angeles Primordialist and constructivist authors have debated the nature of ethnicity “as such” and therefore failed to explain why its charac- teristics vary so dramatically across cases, displaying different de- grees of social closure, political salience, cultural distinctiveness, and historical stability. The author introduces a multilevel process theory to understand how these characteristics are generated and trans- formed over time. The theory assumes that ethnic boundaries are the outcome of the classificatory struggles and negotiations between actors situated in a social field. Three characteristics of a field—the institutional order, distribution of power, and political networks— determine which actors will adopt which strategy of ethnic boundary making. The author then discusses the conditions under which these negotiations will lead to a shared understanding of the location and meaning of boundaries. The nature of this consensus explains the particular characteristics of an ethnic boundary. A final section iden- tifies endogenous and exogenous mechanisms of change. TOWARD A COMPARATIVE SOCIOLOGY OF ETHNIC BOUNDARIES Beyond Constructivism The comparative study of ethnicity rests firmly on the ground established by Fredrik Barth (1969b) in his well-known introduction to a collection 1 Various versions of this article were presented at UCLA’s Department of Sociology, the Institute for Migration Research and Intercultural Studies of the University of Osnabru¨ ck, Harvard’s Center for European Studies, the Center for Comparative Re- search of Yale University, the Association for the Study of Ethnicity at the London School of Economics, the Center for Ethnicity and Citizenship of the University of Bristol, the Department of Political Science and International Relations of University College Dublin, and the Department of Sociology of the University of Go¨ttingen. -

AS-3438-20/AA Recommended Core Competencies for Ethnic Studies

ACADEMIC SENATE OF THE CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY AS-3438-20/AA September 17-18, 2020 RECOMMENDED CORE COMPETENCIES FOR ETHNIC STUDIES: RESPONSE TO CALIFORNIA EDUCATION CODE 89032C RESOLVED: That the ASCSU acknowledge that the California Education Code 89032c requires “The California State University shall collaborate with the California State University Council on Ethnic Studies and the Academic Senate of the California State University to develop core competencies* to be achieved by students who complete an ethnic studies course…”, and be it further RESOLVED: That the ASCSU recommend the adoption of the following five core ethnic studies competencies iteratively developed by the CSU Council on Ethnic Studies and the ASCSU: • analyze and articulate concepts of ethnic studies, including but not limited to race and ethnicity, racialization, equity, ethno-centrism, eurocentrism, white supremacy, self-determination, liberation, decolonization and anti-racism. • apply theory to describe critical events in the histories, cultures, and intellectual traditions, with special focus on the lived- experiences and social struggles of one or more of the following four historically defined racialized core groups: Native Americans, African Americans, Latina/o Americans, and/or Asian Americans, and emphasizing agency and group-affirmation. • critically discuss the intersection of race and ethnicity with other forms of difference affected by hierarchy and oppression, such as class, gender, sexuality, religion, spirituality, national origin, immigration status, ability, and/or age. • describe how struggle, resistance, social justice, solidarity, and liberation as experienced by communities of color are relevant to current issues. • demonstrate active engagement with anti-racist issues, practices and movements to build a diverse, just, and equitable society beyond the classroom. -

Ethnic Studies Review (ESR) Is the Journal of the National Association for Ethnic Studies (NAES)

The National Association for Ethnic Studies Ethnic Studies Review (ESR) is the journal of the National Association for Ethnic Studies (NAES). ESR is a multi-disciplinary international journal devoted to the study of ethnicity, ethnic groups and their cultures, and intergroup relations. NAES has as its basic purpose the promotion of activities and scholarship in the field of Ethnic Studies. The Association is open to any person or institution and serves as a forum for its members in promoting research, study, and curriculum as well as producing publications of interest in the field. NAES sponsors an annual spring conference. General Editor: Faythe E. Turner, Greenfield Community College Book Review Editor: Jonathan A. Majak, University of Wisconsin-Lacrosse Editorial Advisory Board Edna Acosta-Belen Rhett S. Jones University at Albany, SUNY Brown University Jorge A. Bustamante Paul Lauter El Colegio de la Frontera Norte (Mexico) Trinity College Duane W. Champagne Robert L. Perry University of California, Los Angeles Eastern Michigan University Laura Coltelli Otis L. Scott Universita de Pisa (Italy) California State University Sacramento Russell Endo Alan J. Spector University of Colorado Purdue University, Calumet David M. Gradwohl K. Victor Ujimoto Iowa State University University of Guelph (Canada) Maria Herrera-Sobek John C. Walter University of California, Irvine University of Washington Evelyn Hu-DeHart Bernard Young University of Colorado, Boulder Arizona State University Designed by Eileen Claveloux Ethnic Studies Review (ESR) is published by the National Associaton for Ethnic Studies for its individual members and subscribing libraries and institutions. NAES is a member of the Council of Editors of Learned Journals. -

“They Tried to Bury Us, but They Didn't Know We Were Seeds.” “Trataron De Enterrarnos, Pero No Sabían Que Éramos Semil

"They Tried to Bury Us, But They Didn't Know We Were Seeds." "Trataron de Enterrarnos, Pero No Sabían Que Éramos Semillas" - The Mexican American/Raza Studies Political and Legal Struggle: A Content Analysis Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Arce, Martin Sean Citation Arce, Martin Sean. (2020). "They Tried to Bury Us, But They Didn't Know We Were Seeds." "Trataron de Enterrarnos, Pero No Sabían Que Éramos Semillas" - The Mexican American/Raza Studies Political and Legal Struggle: A Content Analysis (Doctoral dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA). Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 24/09/2021 20:52:15 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/656744 “THEY TRIED TO BURY US, BUT THEY DIDN’T KNOW WE WERE SEEDS.” “TRATARON DE ENTERRARNOS, PERO NO SABÍAN QUE ÉRAMOS SEMILLAS.” - THE MEXICAN AMERICAN/RAZA STUDIES POLITICAL AND LEGAL STRUGGLE: A CONTENT ANALYSIS by Martín Arce ______________________________ Copyright © Martín Arce 2020 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF TEACHING, LEARNING & SOCIOCULTURAL STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2020 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Without the love and support of my familia, the completion of this dissertation would not have been possible. My brothers Tom Arce, Gil Arce, and Troy Arce are foundational to my upbringing and to who I am today. -

The Importance of Collecting Data and Doing Social Scientific Research on Race ABOUT the AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

STATEMENT OF THE AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION ON The Importance of Collecting Data and Doing Social Scientific Research on Race ABOUT THE AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION The American Sociological Association (ASA), founded in 1905, is a non-profit membership association dedicated to serving sociologists in their work, advancing sociology as a scientific discipline and profession, and promoting the contributions and use of sociology to society. As the national organization for 13,000 sociologists, the ASA is well positioned to provide a unique set of benefits to its members and to promote the vitality, visibility, and diversity of the discipline. Working at the national and international levels, the Association aims to articulate policy and implement programs likely to have the broadest possible impact for sociology now and in the future. William T. Bielby President Barbara F. Reskin Past-President Michael Burawoy President-Elect Sally T. Hillsman Executive Officer Cite publication as: American Sociological Association. 2003. The Importance of Collecting Data and Doing Social Scientific Research on Race. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association. For Information: American Sociological Association 1307 New York Avenue NW, Suite 700 Washington, DC 20005-4701 Telephone: (202) 383-9005 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.asanet.org Copyright © 2003 by the American Sociological Association The Importance of Collecting Data and Doing Social Scientific Research on Race The question of whether to collect statistics that allow the comparison of differences among racial and ethnic groups in the census, public surveys, and administrative databases is not an abstract one. Some scholarly and civic leaders believe that measuring these differences promotes social divisions and fuels a mistaken perception that race is a biological concept. -

Ethnicity, Multiculturalism and the Problem of Culture

Ethnicity, Multiculturalism and the Problem of Culture Aleksandra Ålund The self-archived postprint version of this journal article is available at Linköping University Institutional Repository (DiVA): http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-45213 N.B.: When citing this work, cite the original publication. This is an electronic version of an article published in: Ålund, A., (1999), Ethnicity, Multiculturalism and the Problem of Culture, European Societies, 1(1), 105-116. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.1999.10749927 Original publication available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.1999.10749927 Copyright: Taylor & Francis (Routledge) (SSH Titles - no Open Select) http://www.routledge.com/ ETHNICITY, MULTICULTURALISM AND THE PROBLEM OF CULTURE Aleksandra Alund Universityof UmeA, Sweden Abstract: This articlediscusses the complex meaning of ethnicity and identity in the multicultural society of today with reference to Swedish society. Sweden, a pronouncedly multiethnic society, is today undergoing division along ethnic lines. Social inequalities tend to be understood in terms of cultural difference. This development seems to be characteristic of most European countries. Culture is usually connected with ethnicity and race and understood as pure, as an 'essence', as related to some original and eternal ethnic core. In this way importantaspects of cultural dynamic in multicultural societya re leftunobserved. What is usually not recognized are cultural crossings and the emergence of composite identities. Within the framework of multicultural society new cultures, identities and ethnicities are created. Departing from some general features of the dominant discourse on ethnicity, its historical roots and its relations to culture and multiculturalism, I discuss problems of cultural essentialism. -

Ethnic Studies Minor Update Proposal Submitted to the Academic Senate

Ethnic Studies Minor Update Proposal submitted to the Academic Senate of Westmont College By Dinora Cardoso, Jason Cha, Kya Mangrum, Felicia Song, Meredith Whitnah, and Sameer Yadav March 19, 2020 Proposal Summary and Rationale We propose an update to the Ethnic Studies Minor as it is currently listed in the College Catalog. Our aim is to better reflect our current course listings, reinvigorate attention to scholarly work around race and ethnicity, and provide institutional support and faculty expertise for campus conversations concerning race and ethnicity. We propose to keep the existing structure of the Minor, but to update the elective offerings and provide an institutional home for the Minor. We also request additional institutional support to allow the Minor to thrive as a vibrant intellectual community within the College that will prepare students to engage with issues of diversity and equity with greater depth and breadth of knowledge. In addition to better serving our current students, we also anticipate that the Ethnic Studies Minor can become an attractive feature of our college curriculum as the changing demographic trends for incoming students will bring in more students, especially students of color, who may particularly be interested in pursuing this minor. We see this Minor as essential to Westmont’s mission as a Christian liberal arts institution that seeks to prepare our students faithfully to engage and to lead in the pluralistic environment that is our contemporary world. Fundamentally interdisciplinary and concerned with issues of both historical and contemporary significance, the Ethnic Studies Minor provides needed institutional space and support for intellectual inquiry around complex and pressing issues faced both by American society generally and American Christianity specifically. -

U.S. Teacher Education, and the Need to Address Systemic Injustices

SEVEN TRENDS IN U.S. TEACHER EDUCATION, AND THE NEED TO ADDREss SYstEMIC INJustICES Photograph by Jodi Miller for The Ohio State University Education Deans for Justice and Equity In partnership with the National Education Policy Center October 2019 National Education Policy Center School of Education, University of Colorado Boulder Boulder, CO 80309-0249 (802) 383-0058 nepc.colorado.edu Acknowledgements NEPC Staff Kevin Welner Project Director William Mathis Managing Director Alex Molnar Publications Director Publication Type: For Your Information (FYI) documents present important content in a brief, engaging manner intended to promote further learning or action. Suggested Citation: Education Deans for Justice and Equity (2019). Seven Trends in U.S. Teacher Education, and the Need to Address Systemic Injustices. Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center. Retrieved [date] from http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/seven-trends This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. This material is provided free of cost to NEPC’s readers, who may make non-commercial use of the material as long as NEPC and its author(s) are credited as the source. For inquiries about commercial use, please contact NEPC at [email protected]. http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/seven-trends 2 of 16 SEVEN TRENDS IN U.S. TEACHER EDUCATION, AND THE NEED TO ADDREss SYstEMIC INJustICES Education Deans for Justice and Equity In partnership with the National Education Policy Center Teachers are important, as is their preparation. We, Education Deans for Justice and Equity, support efforts to improve both. But improving teaching and teacher education must be part of larger efforts to advance equity in society.