Ethnicity, Multiculturalism and the Problem of Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cooperation Across Cultures: an Analysis of Intercultural Competence in Development Organizations

Lisa Armbruster COOPERATION ACROSS CULTURES: AN ANALYSIS OF INTERCULTURAL COMPETENCE IN DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS WORKING PAPER VOLUME | 205 BOCHUM 2014 www.development-research.org | www.ruhr-uni-bochum.de IEE WORKING PAPERS 205 Lisa Armbruster COOPERATION ACROSS CULTURES: AN ANALYSIS OF INTERCULTURAL COMPETENCE IN DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS Copyright 2014 Herausgeber: © Institut für Entwicklungsforschung und Entwicklungspolitik der Ruhr-Universität Bochum Postfach 10 21 48, D-44780 Bochum E-Mail: [email protected] www.development-research.org ISSN 0934-6058 ISBN 978-3-927276-91-8 Abstract Behavior, attitudes, and values differ extremely throughout the world. Whenever two members of different groups such as cultures, nations, or societies interact, such differ- ences become a determining factor for the process of interaction. When thinking of such areas where interactions among members of different cultures constitute a crucial pre- condition, development cooperation comes to one’s mind right away. Development policy and cooperation take place in intercultural settings as members of so-called more devel- oped countries interfere in the development of so-called less developed countries, which always includes a cultural component. Hence, such international and intercultural inter- actions require a competent way of dealing with cultural differences. Consequently, this paper examines the extent to what intercultural competence is a determining factor for the success of organizations of development cooperation. It does so by analyzing the case of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) in Bolivia. Bolivia rep- resents a highly interesting context for studies dealing with interculturality as the country has passed a constitution in 2006 which explicitly includes concepts of interculturality (interculturalidad). -

Enculturation Trajectories and Individual Attainment: an Interactional Language Use Model of Cultural Dynamics in Organizations

IRLE IRLE WORKING PAPER #107-16 March 2016 Enculturation Trajectories and Individual Attainment: An Interactional Language Use Model of Cultural Dynamics in Organizations Sameer B. Srivastava, Amir Goldberg, V. Govind Manian, and Christopher Potts Cite as: Sameer B. Srivastava, Amir Goldberg, V. Govind Manian, and Christopher Potts. (2016). “Enculturation Trajectories and Individual Attainment: An Interactional Language Use Model of Cultural Dynamics in Organizations”. IRLE Working Paper No. 107-16. http://irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/107-16.pdf irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers Enculturation Trajectories and Individual Attainment: An Interactional Language Use Model of Cultural Dynamics in Organizations Sameer B. Srivastava Haas School of Business, University of California, Berkeley Amir Goldberg* Stanford Graduate School of Business V. Govind Manian Stanford Graduate School of Business Christopher Potts Department of Linguistics, Stanford University How do people adapt to organizational culture and what are the consequences for their outcomes in the organization? These fundamental questions about culture have previously been examined using self-report measures, which are subject to reporting bias, rely on coarse cultural categories defined by researchers, and provide only static snapshots of cultural fit. In contrast, we develop an interactional language use model that overcomes these limitations and opens new avenues for theoretical development about the dynamics of organizational culture. To illustrate the power of this approach, we trace the enculturation trajectories of employees in a mid-sized technology firm based on analyses of 10.24 million internal emails. Our language- based measure of changing cultural fit: (1) predicts individual attainment; (2) reveals distinct patterns of adaptation for employees who exit voluntarily, exit involuntarily, and remain employed; and (3) demonstrates that rapid early cultural adaptation reduces the risk of involuntary, but not voluntary, exit. -

Cultural Materialism and Behavior Analysis: an Introduction to Harris Brian D

The Behavior Analyst 2007, 30, 37–47 No. 1 (Spring) Cultural Materialism and Behavior Analysis: An Introduction to Harris Brian D. Kangas University of Florida The year 2007 marks the 80th anniversary of the birth of Marvin Harris (1927–2001). Although relations between Harris’ cultural materialism and Skinner’s radical behaviorism have been promulgated by several in the behavior-analytic community (e.g., Glenn, 1988; Malagodi & Jackson, 1989; Vargas, 1985), Harris himself never published an exclusive and comprehensive work on the relations between the two epistemologies. However, on May 23rd, 1986, he gave an invited address on this topic at the 12th annual conference of the Association for Behavior Analysis in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, entitled Cultural Materialism and Behavior Analysis: Common Problems and Radical Solutions. What follows is the publication of a transcribed audio recording of the invited address that Harris gave to Sigrid Glenn shortly after the conference. The identity of the scribe is unknown, but it has been printed as it was written, with the addendum of embedded references where appropriate. It is offered both as what should prove to be a useful asset for the students of behavior who are interested in the studyofcultural contingencies, practices, and epistemologies, and in commemoration of this 80th anniversary. Key words: cultural materialism, radical behaviorism, behavior analysis Cultural Materialism and Behavior Analysis: Common Problems and Radical Solutions Marvin Harris University of Florida Cultural materialism is a research in rejection of mind as a cause of paradigm which shares many episte- individual human behavior, radical mological and theoretical principles behaviorism is not radically behav- with radical behaviorism. -

Queer Theory, Ethno/Musicology, and the Disorientation of the Field

Queer Theory, Ethno/Musicology, and the Disorientation of the Field Steven Moon We spend significant time and space in our academic lives positioning ourselves: within the theory of the field, in regard to the institution, within networks of interlocutors, scholars, performers, and so on. We are likewise trained to critique those positions, to identify modes of power in their myriad manifestations, and to work towards more equitable methods and theory. That is, we constantly are subject to attempts of disciplinary orienta- tion, and constantly negotiate forms of re-orientation. Sara Ahmed reminds us that we might ask not only how we are oriented within our discipline, but also about 1) how the discipline itself is oriented, and 2) how orien- tation within sexuality shapes how our bodies extend into space (2006). This space—from disciplinary space, to performance space, to the space of fieldwork and the archive—is a boundless environment cut by the trails of the constant reorientation of those before us. But our options are more than the dichotomy between “be oriented” and “re-orient oneself.” In this essay, I examine the development of the ethno/musicologies’ (queer) theoretical borrowings from anthropology, sociology, and literary/cultural studies in order to historicize the contemporary queer moment both fields are expe- riencing and demonstrate the ways in which it might dis-orient the field. I trace the histories of this queer-ing trend by beginning with early concep- tualizations of the ethno/musicological projects, scientism, and quantita- tive methods. This is in relation to the anthropological method of ethno- cartography in order to understand the historical difficulties in creating a queer qualitative field, as opposed to those based in hermeneutics. -

Ethnicity, Confession and Intercultural Dialogue at the European Union's

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Ethnicity, Confession and Intercultural Dialogue at the European Union’s East Border Brie, Mircea and Horga, Ioan and Şipoş, Sorin University of Oradea, Romania 2011 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/44082/ MPRA Paper No. 44082, posted 31 Jan 2013 05:28 UTC ETHNICITY, CONFESSION AND INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE AT THE EUROPEAN UNION EASTERN BORDER ETHNICITY, CONFESSION AND INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE AT THE EUROPEAN UNION EASTERN BORDER Mircea BRIE Ioan HORGA Sorin ŞIPOŞ (Coordinators) Debrecen/Oradea 2011 This present volume contains the papers of the international conference Ethnicity, Confession and Intercultural Dialogue at the European Union‟s East Border, held in Oradea between 2nd-5th of June 2011, organized by Institute for Euroregional Studies Oradea-Debrecen, University of Oradea and Department of International Relations and European Studies, with the support of the European Commission and Bihor County Council. CONTENTS INTRODUCTORY STUDIES Mircea BRIE Ethnicity, Religion and Intercultural Dialogue in the European Border Space.......11 Ioan HORGA Ethnicity, Religion and Intercultural Education in the Curricula of European Studies .......19 MINORITY AND MAJORITY IN THE EASTERN EUROPEAN AREA Victoria BEVZIUC Electoral Systems and Minorities Representations in the Eastern European Area........31 Sergiu CORNEA, Valentina CORNEA Administrative Tools in the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Ethnic Minorities .............................................................................................................47 -

African Refugee Youth's Experiences of Navigating Different Cultures in Canada

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article African Refugee Youth’s Experiences of Navigating Different Cultures in Canada: A “Push and Pull” Experience Roberta L. Woodgate 1,* and David Shiyokha Busolo 2 1 Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, College of Nursing, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB R3T 2N2, Canada 2 Faculty of Nursing, University of New Brunswick, Moncton, NB E1C 0L2, Canada; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Refugee youth face challenges in navigating different cultures in destination countries and require better support. However, we know little about the adaptation experiences of African refugee youth in Canada. Accordingly, this paper presents the adaptation experiences of African refugee youth and makes recommendations for ways to support youth. Twenty-eight youth took part in semi-structured interviews. Using a thematic analysis approach, qualitative data revealed four themes of: (1) ‘disruption in the family,’ where youth talked about being separated from their parent(s) and the effect on their adaptation; (2) ‘our cultures are different,’ where youth shared differences between African and mainstream Canadian culture; (3) ‘searching for identity: a cultural struggle,’ where youth narrated their struggles in finding identity; and (4) ‘learning the new culture,’ where youth narrated how they navigate African and Canadian culture. Overall, the youth presented with challenges in adapting to cultures in Canada and highlighted how these struggles were influenced Citation: Woodgate, R.L.; Busolo, D.S. African Refugee Youth’s by their migration journey. To promote better settlement and adaptation, youth could benefit from Experiences of Navigating Different supports and activities that promote cultural awareness with attention to their migration experiences. -

Durkheim and Organizational Culture

IRLE IRLE WORKING PAPER #108-04 June 2004 Durkheim and Organizational Culture James R. Lincoln and Didier Guillot Cite as: James R. Lincoln and Didier Guillot. (2004). “Durkheim and Organizational Culture.” IRLE Working Paper No. 108-04. http://irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/108-04.pdf irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers Durkheim and Organizational Culture James R. Lincoln Walter A. Haas School of Business University of California Berkeley, CA 94720 Didier Guillot INSEAD Singapore June , 2004 Prepared for inclusion in Marek Kocsynski, Randy Hodson, and Paul Edwards (editors): Social Theory at Work . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Durkheim and Organizational Culture “The degree of consensus over, and intensity of, cognitive orientations and regulative cultural codes among the members of a population is an inv erse function of the degree of structural differentiation among actors in this population and a positive, multiplicative function of their (a) rate of interpersonal interaction, (b) level of emotional arousal, and (c) rate of ritual performance. ” Durkheim’ s theory of culture as rendered axiomatically by Jonathan Turner (1990) Introduction This paper examines the significance of Emile Durkheim’s thought for organization theory , particular attention being given to the concept of organizational culture. We ar e not the first to take the project on —a number of scholars have usefully addressed the extent and relevance of this giant of Western social science for the study of organization and work. Even so, there is no denying that Durkheim’s name appears with vast ly less frequency in the literature on these topics than is true of Marx and W eber, sociology’ s other founding fathers . -

Literacy As a Socio-Cultural Tool’ Cindy Bird

FOCUS ON PRACTICE When Cultures Meet When Cultures Meet, What’s a Teacher To Do? Highlighting the ‘Cultural’ in ‘Literacy as a Socio-cultural Tool’ Cindy Bird ABSTRACT Cultures determine identity in that they prescribe the “food, festivals, and fashion” of their members; for example, rap music, baggy pants and gestured dancing identify the hip hop culture (recognizable to both “members” and “non-members”). Cultural identities are created and maintained by “literacy” -- the ability to read and write the “texts” of a culture. Thus in this broad sense, literacy is a socio-cultural “tool,” and mastering it means “success” within a culture. The purpose of this article is to explore the socio-cultural nature of literacy as it relates to identity both for teacher and student, and to examine the use of literacy as a tool for “success” in the culture of school. The article concludes by delineating four pedagogical choices: the “uni-cultural,” the “uni- cultural plus,” the “multi-cultural as motivator,” and the “multi-cultural as curriculum.” These are available to all teachers who stand in their classroom doorways at the meeting place of multiple cultures -- their own, the school’s, the classroom’s, and their students’. AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY Cindy M. Bird is Assistant Professor of Education in the Graduate Literacy Program at the State University of New York at Fredonia, where she currently teaches the Sociological and Psychological Foundations of Literacy courses. Her areas of expertise include adolescent literacies and media literacy. She may be reached at [email protected] Not long ago I heard a commencement address wherein the speaker spent several minutes listing the multiple communities to which an individual belongs. -

Cultural Theorizing Has Dramatically Increased

Cultural CHAPTER 9 Theorizing Another Embarassing Confession Like the concept of social structure, the conceptualization of culture in sociology is rather vague, despite a great deal of attention by sociologists to the properties and dynamics of cul- ture. There has always been the recognition that culture is attached to social structures, and vice versa, with the result that sociologists often speak in terms of sociocultural formations or sociocultural systems and structures. This merging of structure and culture rarely clarifies but, instead, further conflates a precise definition of culture. And so, sociology’s big idea— culture—is much like the notion of social structure. Its conceptualization is somewhat meta- phorical, often rather imprecise, and yet highly evocative. There is no consensus in defini- tions of culture beyond the general idea that humans create symbol systems, built from our linguistic capacities, which are used to regulate conduct. And even this definition would be challenged by some. Since the 1980s and accelerating with each decade, the amount of cultural theorizing has dramatically increased. Mid-twentieth-century functional theory had emphasized the importance of culture but not in a context-specific or robust manner; rather, functional- ism viewed culture as a mechanism by which actions are controlled and regulated,1 whereas much of the modern revival of culture has viewed culture in a much more robust and inclusive manner. When conflict theory finally pushed functionalism from center stage, it also tended to bring forth a more Marxian view of culture as a “superstructure” generated by economic substructures. Culture became the sidekick, much like Tonto for the Lone Ranger, to social structure, with the result that its autonomy and force indepen- dent of social structures were not emphasized and, in some cases, not even recognized. -

Complementary International Standards First Session Geneva, 11-22 February 2008

UNITED NATIONS A General Assembly Distr. GENERAL A/HRC/AC.1/1/CRP.4 18 February 2008 Original: ENGLISH ONLY HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL Ad Hoc Committee on the Elaboration of Complementary International Standards First session Geneva, 11-22 February 2008 COMPLEMENTARY INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS COMPILATION OF CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE STUDY BY THE FIVE EXPERTS ON THE CONTENT AND SCOPE OF SUBSTANTIVE GAPS IN THE EXISTING INTERNATIONAL INSTRUMENTS TO COMBAT RACISM RACIAL DISCRIMINATION, XENOPHOBIA AND RELATED INTOLERANCE A/HRC/AC.1/1/CRP.4 Page 2 I. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ON THE CONTENT AND SCOPE OF SUBSTANTIVE GAPS ON COMPLEMENTARY INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS WITH REGARD TO POSITIVE OBLIGATIONS OF STATES PARTIES Assessment and recommendations 1. The role of human rights education 29. The DDPA underlines the importance of human rights education as a key to changing attitudes and behaviour and to promoting tolerance and respect for diversity in societies1 and, therefore as crucial in the struggle against racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance.2 The importance of human rights education is also underlined in several other human rights documents. The Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action assert that “human rights education, training and public information are essential for the promotion and achievement of stable and harmonious relations among communities and for fostering mutual understanding, tolerance and peace.”3 The World Programme for Human Rights Education identifies the promotion of understanding, tolerance, gender equality and friendship among all nations, indigenous peoples and racial, national, ethnic, religious and linguistic groups as one of the constitutive elements of human rights education that aims at building a universal culture of human rights.4 The 2005 World Summit Outcome calls for the implementation of the World Programme for Human Rights Education and encourages all States to develop initiatives in this regard.5 30. -

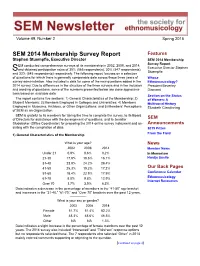

SEM 2014 Membership Survey Report Features Stephen Stuempfle, Executive Director SEM 2014 Membership

Volume 49, Number 2 Spring 2015 SEM 2014 Membership Survey Report Features Stephen Stuempfle, Executive Director SEM 2014 Membership EM conducted comprehensive surveys of its membership in 2002, 2008, and 2014, Survey Report Executive Director Stephen and obtained participation rates of 35% (565 respondents), 30% (547 respondents), S Stuempfle and 32% (545 respondents) respectively. The following report focuses on a selection of questions for which there is generally comparable data across these three years of Whose survey administration. Also included is data for some of the new questions added in the Ethnomusicology? 2014 survey. Due to differences in the structure of the three surveys and in the inclusion President Beverley and wording of questions, some of the numbers presented below are close approxima- Diamond tions based on available data. Section on the Status The report contains five sections: 1) General Characteristics of the Membership; 2) of Women: A Student Members; 3) Members Employed in Colleges and Universities; 4) Members Multivocal History Employed in Museums, Archives, or Other Organizations; and 5) Members’ Perceptions Elizabeth Clendinning of SEM as an Organization. SEM is grateful to its members for taking the time to complete the survey, to its Board of Directors for assistance with the development of questions, and to Jennifer SEM Studebaker (Office Coordinator) for preparing the 2014 online survey instrument and as- Announcements sisting with the compilation of data. 2015 Prizes From the Field 1) General Characteristics of the Membership What is your age? News 2002 2008 2014 Member News Under 21 0.9% 0.6% 0.2% In Memoriam 21-30 17.9% 19.6% 16.1% Hardja Susilo 31-40 23.9% 24.2% 29.4% 41-50 25.3% 19.2% 17.2% Our Back Pages 51-60 18.4% 22.9% 17.9% Conference Calendar 61-70 8.0% 9.8% 12.9% Ethnomusicology Internet Resources Over 70 3.7% 3.9% 6.3% Data indicates a decrease in the percentage of members in the “41-50” age bracket and increases in the “31-40,” “61-70,” and “Over 70” brackets over the past 12 years. -

Philosophy Emerging from Culture

Cultural Heritage and Contemporary Change Series I. Culture and Values, Volume 42 General Editor: George F. McLean Associate General Editor: William Sweet Philosophy Emerging from Culture Edited by William Sweet George F. McLean Oliva Blanchette Wonbin Park The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Copyright © 2013 by The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Box 261 Cardinal Station Washington, D.C. 20064 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Philosophy emerging from culture / edited by William Sweet, George F. McLean, Oliva Blanchette. -- 1st [edition]. pages cm. -- (Cultural heritage and contemporary change. Series I, Culture and values ; Volume 42) 1. Philosophy and civilization. 2. Philosophy. 3. Culture. I. Sweet, William, editor of compilation. B59.P57 2013 2013015164 100--dc23 CIP ISBN 978-1-56518-285-1 (pbk.) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: Philosophy Emerging From Culture 1 William Sweet and George F. McLean Part I: The Dynamics of Change Chapter I. What Remains of Modernity? Philosophy and 25 Culture in the Transition to a Global Era William Sweet Chapter II. Principles of Western Bioethics and 43 the HIV/AIDS Epidemic in Africa Workineh Kelbessa Chapter III. Rationality in Islamic Peripatetic and 71 Enlightenment Philosophies Sayyed Hassan Houssaini Chapter IV. Theanthropy and Culture According to Karol Wojtyla 87 Andrew N. Woznicki Chapter V. Al-Fārābī’s Approach to Aristotle’s Eudaimonia 99 Mostafa Younesie Part II: The Nature of Culture and its Potential as a Philosophical Source Chapter VI. A Realistic Interpretation of Culture 121 Jeu-Jenq Yuann Chapter VII. Rehabilitating Value: Questions of 145 Meaning and Adequacy Karim Crow Chapter VIII.