Filipino Americans and Polyculturalism in Seattle, Wa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transculturalism in Chicano Literature, Visual Art, and Film Master's

Transculturalism in Chicano Literature, Visual Art, and Film Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Global Studies Jerónimo Arellano, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Global Studies by Sarah Mabry August 2018 Transculturalism in Chicano Literature, Visual Art, and Film Copyright by Sarah Mabry © 2018 Dedication Here I acknowledge those individuals by name and those remaining anonymous that have encouraged and inspired me on this journey. First, I would like to dedicate this to my great grandfather, Jerome Head, a surgeon, published author, and painter. Although we never had the opportunity to meet on this earth, you passed along your works of literature and art. Gleaned from your manuscript entitled A Search for Solomon, ¨As is so often the way with quests, whether they be for fish or buried cities or mountain peaks or even for money or any other goal that one sets himself in life, the rewards are usually incidental to the journeying rather than in the end itself…I have come to enjoy the journeying.” I consider this project as a quest of discovery, rediscovery, and delightful unexpected turns. I would like mention one of Jerome’s six sons, my grandfather, Charles Rollin Head, a farmer by trade and an intellectual at heart. I remember your Chevy pickup truck filled with farm supplies rattling under the backseat and a tape cassette playing Mozart’s piano sonata No. 16. This old vehicle metaphorically carried a hard work ethic together with an artistic sensibility. -

Molos Dimitrios 201212 Phd.Pdf (1.418Mb)

CULTURE, COMMUNITY AND THE MULTICULTURAL INDIVIDUAL Liberalism and the Challenge of Multiculturality by DIMITRIOS (JIM) MOLOS A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in Philosophy in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada December, 2012 Copyright © Dimitrios (Jim) Molos, 2012 ABSTRACT Every theory of liberal multiculturalism is premised on some account of the nature of culture, cultural difference and social reality, or what I call “the conditions of multi- culturality”. In this dissertation, I offer a revised account of the conditions and challenge of multiculturality. Beginning with the widely accepted idea that individuals depend on both culture and community as social preconditions for choice, freedom and autonomy, and informing this idea with collectivist and individualist lessons from Tyler Burge’s famous externalist thought-experiment, my analysis shows that social contexts are multi- cultural when they are characterized by a plurality of social communities offering distinct sets of cultural norms, and individuals are multicultural to the extent that they are capable of using cultural norms from various social communities. The depth, pervasiveness, and complexity of multiculturality raises important normative questions about fair and just terms for protecting and promoting social communities under conditions of internal and external cultural contestation, and these questions are not only restricted to cases involv- ing internal minorities. As a theory of cultural justice, liberal multiculturalism must respond to the challenge of multiculturality generated by cultural difference per se, but it cannot do so adequately in all cases armed with only the traditional tools of toleration, freedom of association and exit, fundamental rights and freedoms, and internal political autonomy. -

Queer Theory, Ethno/Musicology, and the Disorientation of the Field

Queer Theory, Ethno/Musicology, and the Disorientation of the Field Steven Moon We spend significant time and space in our academic lives positioning ourselves: within the theory of the field, in regard to the institution, within networks of interlocutors, scholars, performers, and so on. We are likewise trained to critique those positions, to identify modes of power in their myriad manifestations, and to work towards more equitable methods and theory. That is, we constantly are subject to attempts of disciplinary orienta- tion, and constantly negotiate forms of re-orientation. Sara Ahmed reminds us that we might ask not only how we are oriented within our discipline, but also about 1) how the discipline itself is oriented, and 2) how orien- tation within sexuality shapes how our bodies extend into space (2006). This space—from disciplinary space, to performance space, to the space of fieldwork and the archive—is a boundless environment cut by the trails of the constant reorientation of those before us. But our options are more than the dichotomy between “be oriented” and “re-orient oneself.” In this essay, I examine the development of the ethno/musicologies’ (queer) theoretical borrowings from anthropology, sociology, and literary/cultural studies in order to historicize the contemporary queer moment both fields are expe- riencing and demonstrate the ways in which it might dis-orient the field. I trace the histories of this queer-ing trend by beginning with early concep- tualizations of the ethno/musicological projects, scientism, and quantita- tive methods. This is in relation to the anthropological method of ethno- cartography in order to understand the historical difficulties in creating a queer qualitative field, as opposed to those based in hermeneutics. -

Strong Cultures and Subcultures in Dynamic Organizations

02-091 The Role of Subcultures in Agile Organizations Alicia Boisnier Jennifer A. Chatman1 1 The second author wrote this paper while a Marvin Bower Fellow at the Harvard Business School and is grateful for their support. We also thank Elizabeth Mannix, Rita McGrath, and an anonymous reviewer for their insightful suggestions. Copyright © 2002 by Alicia Boisnier and Jennifer A. Chatman Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. The Role of Subcultures in Agile Organizations Alicia Boisnier and Jennifer A. Chatman1 Haas School of Business University of California, Berkeley May 24, 2002 To appear in, R. Petersen and E. Mannix, Leading and managing people in dynamic organizations. Forthcoming, 2002. 1 The second author wrote this paper while a Marvin Bower Fellow at the Harvard Business School and is grateful for their support. We also thank Elizabeth Mannix, Rita McGrath, and an anonymous reviewer for their insightful suggestions. 2 Organizations face increasingly dynamic environments characterized by substantial, and often unpredictable technological, political, and economic change. How can organizations respond rapidly to such changes or become more agile? Organizational agility, according to Lee Dyer, “requires a judicious mix of stability and reconfigurability” (2001: 4). We consider an unlikely source of agility: organizational culture. This may seem like an odd juxtaposition since strong unitary cultures exert a stabilizing force on organizations by encouraging cohesion, organizational commitment, and desirable work behaviors among members (e.g., Deal & Kennedy, 1982; Nemeth & Staw, 1989; O'Reilly & Chatman, 1986). -

"Model Minority" Myth Shuzi Meng | Soobin Im | Stephanie Campbell, MS YWCA Racial Justice Summit | Madison, WI 15 October 2019

Minoritized Yet Excluded: Dismantling the "Model Minority" Myth Shuzi Meng | Soobin Im | Stephanie Campbell, MS YWCA Racial Justice Summit | Madison, WI 15 October 2019 AGENDA ● Introductions ● Learning objectives ● What sparked our interest ● Asian Americans, the hyphenated Americans and perpetual foreigners in the U.S. ● Hidden in the Black/White racial binary ● The Model Minority myth: What’s wrong with the positive stereotype? ● Activity: The myth crusher ● Implications for mental health and education ● Activity: Application to your own occupational/interpersonal settings ● Questions 3 HELLO! ● name ● racial/ethnic identity ● preferred pronouns ● share about: ○ an experience in which you were over- or underestimated ○ your favorite Asian dish or food 4 LEARNING OBJECTIVES ◈ Understand history of Asian Americans in the U.S. and the experiences of discrimination and implicit racial biases against Asian Americans. ◈ Recognize and identify how “positive stereotypes” can hurt not only Asian American communities, but all racial/ethnic groups. ◈ Increase confidence in interacting with and advocating for individuals who fall victim to such biases. 5 What Sparked Our Interest “Say My Name” 6 7 8 Xenophobia? Or beyond? What are the experiences of Asian Americans with U.S. nationality? 9 10 11 DISCUSSION In your table groups… What are your reactions to these videos? Do these resonate with your ideas of Asian Americans? If yes, why? If no, why not? 12 Asian Americans the hyphenated Americans and perpetual foreigners in the U.S. Where are you from? Where were you born? What are you? Your English is very good. 13 “One indication that Asian Americans continue to be viewed as foreigners (i.e., not Americans) is that attitudes toward Asian Americans are highly influenced by international relations between the United States and Asian countries (Lowe, 1996; Nakayama, 1994; Wu, 2002).” - Lee, 2005, p.5 14 HISTORY OF ASIAN AMERICANS IN THE U.S. -

Marshall High School Mr. Cline Sociology Unit Four AB * What Is Culture?

CULTURE Marshall High School Mr. Cline Sociology Unit Four AB * What is Culture? • Integration and Diversity • Imagine that this is the early twentieth century and you are a teacher in a school in New York. Whom would you see around you? Some Irish kids, some Italians, maybe some Armenians, Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, African Americans? How do you reach all of these different languages and cultures to facilitate learning when you do not have the time to teach each one individually in their own way? • There are social forces that would state that assimilation is the way to go about this task. Assimilation is merely the process by which newcomers to America, as well as other “outsiders,” give up their culturally distinct beliefs, values and customs and take on those of the dominant culture. • The opposite viewpoint would acknowledge that there is a tendency to preserve cultural diversity, to keep one’s own personal heritage alive and to respect the rights of others to do so. This is known as multi culturalism. * What is Culture? • Integration and Diversity • The tension between assimilation and multi culturalism is evident in many schools and other public institutions throughout the United States. How much multi culturalism is good for society versus how much we want people to identify and share the common culture of America is an ongoing, and often heated argument. • One result of assimilation is cultural integration, that is the degree to which a culture is a functionally integrated system, so that all the parts fit together well. On another level, the elements of culture are functionally integrated with other facets of society, such as social structure and power relations. -

Sub-National Movements, Cultural Flow, the Modern State and the Malleability of Political Space: from Rational Choice to Transcultural Perspective and Back Again

8 Sub-National Movements, Cultural Flow Sub-National Movements, Cultural Flow, the Modern State and the Malleability of Political Space: From Rational Choice to Transcultural Perspective and Back Again Subrata Mitra, Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Introduction Using the Telengana movement in South India as a template, this article juxtaposes two methods of analysing the phenomenon of sub-national movements (a special type of ethno-national movement) within the larger framework of the challenge of state-formation and nation-building in multi- ethnic, post-colonial states.1 The methods are as follows: first, explanatory models based on conventional tools of comparative politics such as conflicts of interest, fixed national and regional boundaries, and the strategic manoeuvres of political leaders and their followers. Second, a transcultural approach that draws on political perceptions and behaviour influenced by deep memory, cultural flow, and the hybridisation of indigenous and imported categories. This article applies these methods to the Telengana movement in South India, first, within the theoretical perspective of the rational politics of cultural nationalism, and then extending the method to introduce explanatory phenomena that belong more broadly to the transcultural approach. Though the empirical exemplars are drawn mostly from India, the mthod is applicable to the wider world of sub-national challenges to the modern state. Sub-national movements belong to the generic category of collective efforts used to assert cultural nationalism in a territorial space that corresponds to a homeland that its advocates strongly believe to be legitimately theirs. Typically, 1 An earlier version of this article was presented at the annual conference of the Association for Asian Studies, Honolulu, March 31–April 3, 2011. -

The Culture of Support Services

The Culture of Support Services After completing this lesson you will be able to: þ Define the terms cultural capital; dominant culture; institutional bias; macro culture; and micro culture. þ Identify key values and views related to the macro culture of the United States. þ Identify key values and views related to the culture of the human services delivery system. þ Describe some differences in definitions and responses to disability based on culture. þ Give an example of cultural bias found in the use of jargon and disability labels. þ Describe ways in which design and delivery of services, including best practices, can conflict with the culture of people receiving supports. © 2004 College of Direct Support Cultural Competence Lesson 3 page 1 of 12 Terms for Understanding the Culture of Services and Supports In the last lesson you learned a lot about the culture in which you were raised. Learning about your culture helped you understand why you have certain views and beliefs. You got to compare your own views with some views from a few other cultures. These comparative activities will help you be more aware of when there are differences between your culture and others. They will help you learn not to make assumptions about others and they will support you to become more culturally competent. Now, take a minute to write your own definitions for these words. þ Macro culture – þ Dominant culture – þ Micro culture – þ Institutional bias – þ Cultural capital – Macro and Micro culture Macro (dominant) culture is the shared cultural perspective of the largest group. -

Religious Legacies and the Politics of Multiculturalism: a Comparative Analysis of Integration Policies in Western Democracies

RELIGIOUS LEGACIES AND THE POLITICS OF MULTICULTURALISM: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF INTEGRATION POLICIES IN WESTERN DEMOCRACIES Michael Minkenberg Europa-Universitaet Viadrina 2007-1 About the Matthew B. Ridgway Center The Matthew B. Ridgway Center for International Security Studies at the University of Pittsburgh is dedicated to producing original and impartial analysis that informs policymakers who must confront diverse challenges to international and human security. Center programs address a range of security concerns—from the spread of terrorism and technologies of mass destruction to genocide, failed states, and the abuse of human rights in repressive regimes. The Ridgway Center is affiliated with the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs (GSPIA) and the University Center for International Studies (UCIS), both at the University of Pittsburgh. The Ford Institute for Human Security is a constituent unit of the Ridgway Center. This working paper is a product of the Ford Institute for Human Security’s working group on “Immigration, Integration and Security: Europe and America in Comparative Perspective,” co-chaired by Ariane Chebel d’Appollonia and Simon Reich. This paper and the working group that produced it were made possible by a generous grant from the Ford Foundation to the Ridgway Center on The Determinants of Security Policy in the 21st Century, Grant # 1050-1036. Introduction Landmark events of global significance have repeatedly raised issues of policy convergence or divergence across nation states, as well as continuity or stability across time, or a combination of both. This is particularly true for events such as the end of the Cold War, 9/11, the area of immigration and integration policies, the politics of citizenship and multiculturalism. -

BTS' A.R.M.Y. Web 2.0 Composing: Fangirl Translinguality As Parasocial, Motile Literacy Praxis Judy-Gail Baker a Dissertation

BTS’ A.R.M.Y. Web 2.0 Composing: Fangirl Translinguality As Parasocial, Motile Literacy Praxis Judy-Gail Baker A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2019 Reading Committee: Anis Bawarshi, Chair Nancy Bou Ayash Juan C. Guerra Program Authorized to Offer Degree: English ©Copyright 2019 Judy-Gail Baker University of Washington Abstract BTS’ A.R.M.Y. Web 2.0 Composing: Fangirl Translinguality As Parasocial, Motile Literacy Praxis Judy-Gail Baker Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Anis Bawarshi English As a transcultural K-Pop fandom, 아미 [A.R.M.Y.] perform out-of-school, Web 2.0 English[es] composing to cooperatively translate, exchange and broker content for parasocially relating to/with members of the supergroup 방탄소년단 [BTS] and to/with each other. Using critical linguistic ethnography, this study traces how 아미 microbloggers’ digital conversations embody Jenkins’ principles of participatory fandom and Wenger’s characteristics of communities of learning practice. By creating Wei’s multilingual translanguaging spaces, 아미 assemble interest-based collectives Pérez González calls translation adhocracies, who collaboratively access resources, produce content and distribute fan compositions within and beyond fandom members. In-school K-12 and secondary learning writing Composition and Literacy Studies’ theory, research and pedagogy imagine learners as underdeveloped novices undergoing socialization to existing “native” discourses and genres and acquiring through “expert” instruction competencies for formal academic and professional “lived” composing. Critical discourse analysis of 아미 texts documents diverse learners’ initiating, mediating, translating and remixing transmodal, plurilingual compositions with agency, scope and sophistication that challenge the fields’ structural assumptions and deficit framing of students. -

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds an End to Antisemitism!

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds An End to Antisemitism! Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman Volume 5 Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman ISBN 978-3-11-058243-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-067196-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-067203-9 DOI https://10.1515/9783110671964 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number: 2021931477 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, Lawrence H. Schiffman, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com Cover image: Illustration by Tayler Culligan (https://dribbble.com/taylerculligan). With friendly permission of Chicago Booth Review. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com TableofContents Preface and Acknowledgements IX LisaJacobs, Armin Lange, and Kerstin Mayerhofer Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds: Introduction 1 Confronting Antisemitism through Critical Reflection/Approaches -

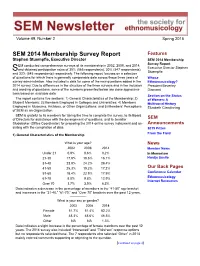

SEM 2014 Membership Survey Report Features Stephen Stuempfle, Executive Director SEM 2014 Membership

Volume 49, Number 2 Spring 2015 SEM 2014 Membership Survey Report Features Stephen Stuempfle, Executive Director SEM 2014 Membership EM conducted comprehensive surveys of its membership in 2002, 2008, and 2014, Survey Report Executive Director Stephen and obtained participation rates of 35% (565 respondents), 30% (547 respondents), S Stuempfle and 32% (545 respondents) respectively. The following report focuses on a selection of questions for which there is generally comparable data across these three years of Whose survey administration. Also included is data for some of the new questions added in the Ethnomusicology? 2014 survey. Due to differences in the structure of the three surveys and in the inclusion President Beverley and wording of questions, some of the numbers presented below are close approxima- Diamond tions based on available data. Section on the Status The report contains five sections: 1) General Characteristics of the Membership; 2) of Women: A Student Members; 3) Members Employed in Colleges and Universities; 4) Members Multivocal History Employed in Museums, Archives, or Other Organizations; and 5) Members’ Perceptions Elizabeth Clendinning of SEM as an Organization. SEM is grateful to its members for taking the time to complete the survey, to its Board of Directors for assistance with the development of questions, and to Jennifer SEM Studebaker (Office Coordinator) for preparing the 2014 online survey instrument and as- Announcements sisting with the compilation of data. 2015 Prizes From the Field 1) General Characteristics of the Membership What is your age? News 2002 2008 2014 Member News Under 21 0.9% 0.6% 0.2% In Memoriam 21-30 17.9% 19.6% 16.1% Hardja Susilo 31-40 23.9% 24.2% 29.4% 41-50 25.3% 19.2% 17.2% Our Back Pages 51-60 18.4% 22.9% 17.9% Conference Calendar 61-70 8.0% 9.8% 12.9% Ethnomusicology Internet Resources Over 70 3.7% 3.9% 6.3% Data indicates a decrease in the percentage of members in the “41-50” age bracket and increases in the “31-40,” “61-70,” and “Over 70” brackets over the past 12 years.