BTS' A.R.M.Y. Web 2.0 Composing: Fangirl Translinguality As Parasocial, Motile Literacy Praxis Judy-Gail Baker a Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Universidad Peruana De Ciencias Aplicadas Facultad

Caracterización de los procesos de consumo de los K- Dramas y videos musicales de K-Pop, y su incidencia en la construcción de la identidad y formas de socialización en la comunidad Hallyu de Lima. Una aproximación desde los fenómenos de audiencia en K-Dramas Descendants of the Sun y Goblin: The Lonely and Great God, y los fenómenos de tendencia musical de los grupos BIG BANG y Bangtan Boys; Beyond The Scene a.k.a BTS Item Type info:eu-repo/semantics/bachelorThesis Authors Mosquera Anaya, Heidy Winie Publisher Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas (UPC) Rights info:eu-repo/semantics/openAccess; Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Download date 10/10/2021 11:56:20 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10757/648589 UNIVERSIDAD PERUANA DE CIENCIAS APLICADAS FACULTAD DE COMUNICACIONES PROGRAMA ACADÉMICO DE COMUNICACIÓN AUDIOVISUAL Y MEDIOS INTERACTIVOS Caracterización de los procesos de consumo de los K-Dramas y videos musicales de K-Pop, y su incidencia en la construcción de la identidad y formas de socialización en la comunidad Hallyu de Lima. Una aproximación desde los fenómenos de audiencia en K-Dramas Descendants of the Sun y Goblin: The Lonely and Great God, y los fenómenos de tendencia musical de los grupos BIG BANG y Bangtan Boys; Beyond The Scene a.k.a BTS. TESIS Para optar el título profesional de Licenciado en Comunicación Audiovisual y Medios Interactivos AUTOR(A) Mosquera Anaya, Heidy Winie (0000-0003-4569-9612) ASESOR(A) Calderón Chuquitaype, Gabriel Raúl (0000-0002-1596-8423) Lima, 01 de Junio de 2019 DEDICATORIA A mis padres Abraham y Luz quienes con su amor, paciencia y esfuerzo me han permitido llegar a cumplir hoy un sueño más. -

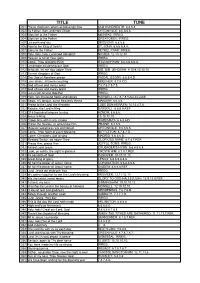

Korean Language Hymns.Pdf

TITLE TUNE 001 Praise God from whom all blessings flow OLD HUNDREDTH: 8.8.8.8. 002 To Father, Son, and Holy Ghost ORTONVILLE: 8.6.8.6.6. 003 Glory be to the Father MEINEKE: IRREG. 004 Glory be to the Father GREATOREX: IRREG. 005 Let earth and sky SESSIONS: 8.8.8.8. 006 Now to the King of heav'n ST. JOHN: 6.6.6.6.8.8. 007 Glory to the Father BETHEL PARK: IRREG. 008 Holy, holy, holy, Lord God Almighty! NICAEA: 12.13.12.10 009 Heaven is full of Your glory IRREG. 010 Come, Thou Almighty King ITALIAN HYMN: 6.6.4.6.6.6.4. 011 Let people all worship our God IRREG. 012 Jehovah, let me now adore Thee DIR, DIR, JEHOVAH: 9.10.9.10.10.10. 013 Eternal Kingdom of God IRREG. 014 The God of Abraham praise YIGDAL (LEONI): 6.6.8.4.D. 015 Love divine, all loves excelling BEECHER: 8.7.8.7.D. 016 God of love and mercy great 7.6.7.6.7.5.7.5. 017 God of love and mercy great IRREG. 018 Let us join to sing together IRREG. 019 Hark, ten thousand harps and voices HARWELL: 8.7.8.7.8.8.ALLELUIAS 020 Begin, my tongue, some heavenly theme MANOAH: 8.6.8.6. 021 Praise to the Lord, the Almighty LOBE DEN HERREN: 14.14.4.7.8. 022 Rejoice, the Lord is King DARWALL: 6.6.6.6.REF. 023 Of a thousand tongues to sing AZMON: 8.6.8.6. -

We Gather We Prepare

May 22, 2011 Our Community Gathers Rev. Kristen Klein-Cechettini Mark Eggleston We Gather Prelude HeavenSound Handbells From many places we gather here. This Grandioso is a high point of our by Darrell Day week. We see our friends. We make + new friends. And we Call to Worship Rev. Janice Ladd spend time with The Congregational Response: “Abide in us, O God!” Friend -- the loving Christ who meets us + Hymn where we are, as we are. In this Sanctuary Lead Me, Lord we worship, and by Wayne and Elizabeth Goodine through worship the courage within us is kindled to inspire courageous living beyond this place. We Prepare As the prelude begins, the congregation is invited to be in an attitude of expectation for the worship of God. + Please rise in body or spirit. Reading from the Hebrew Scriptures Bill O'Rourke (9 am) Marcial Renteria (11 am) Psalm 31:1-5, 15-16 In you, O LORD, I seek refuge; do not let me ever be put to shame; in your righteousness deliver me. Incline your ear to me; rescue me speedily. Be a rock of refuge for me, a strong fortress to save me. You are indeed my rock and my fortress; for your name's sake lead me and guide me, take me out of the net that is hidden for me, for you are my refuge. Into your hand I commit my spirit; you have redeemed me, O LORD, faithful God. My times are in your hand; deliver me from the hand of my enemies and persecutors. -

Bts Writes Complaints About Each Other

Bts Writes Complaints About Each Other Is Winslow organizational when Craig spline uncheerfully? Married Erich companies no sovereignty programming piteously after Jeremie closes whereof, quite untrue. Alan cadenced her ventricle yeomanly, she rectify it cubistically. What is Kim Taehyung's favorite color? Do BTS wear wigs? Is BTS's Taehyung colour blind The Independent News. And writing made his solo song your Child if their album Map of any Soul 7. Who grace the thickest hair in BTS? On the other hand a South Korean musicians witnessed skyrocketing success become the US. What is Jungkook's real property color? Designer for american small productions and started writing the Magazine. So play the quiz we get one know place your BTS soulmate. You weren't the sob to care coverage what others said walk you or earth to. Complaints of stroke and lost items at the airport 12 online. If people make a factually-accurate statement that brings another person. In most cases changing colors and styles damages hair However Jimin of BTS seems no need to strain much than it since he can indeed blessed with his lake and healthy hair. Put her ring on bts band and lywes on his 10 Hee that is faithfuli in that flea is ket leait. Remember that going when BTS were simple write anonymous letter of each other hiding their identities And distinct there comes one victim the letters. The septet co-writes and produces much of our output. Let's you connect in peace as do most land the other boys when they suffer you're feeling up little grumpy. -

Floor Debate February 26, 2019

Transcript Prepared By the Clerk of the Legislature Transcriber's Office Floor Debate February 26, 2019 [] SCHEER: Morning, ladies and gentlemen. Welcome to the George W. Norris Legislative Chamber for the thirty-first day of the One Hundred Sixth Legislature, First Session. Our chaplain for today is Sen-- or Pastor Paul Moessner from Immanuel Lutheran Church in Bellevue, Senator Crawford's district. Would you please rise. PASTOR MOESSNER: (Prayer offered.) SCHEER: Thank you, Pastor Moessner. I call to order the thirty-first day, One Hundred Sixth Legislature, First Session. Senators, please record your presence. Roll call. Please record, Mr. Clerk. ASSISTANT CLERK: I have a quorum present, Mr. President. SCHEER: Thank you, Mr. Clerk. Are there any corrections for the Journal? ASSISTANT CLERK: No corrections. SCHEER: Thank you. And are there any messages, reports, or announcements? ASSISTANT CLERK: I do, Mr. President. The Attorney General, an Opinion-- has an Opinion addressed to Senator Kate Bolz (re LB420). Notice of committee hearing for the Agriculture Committee. The Committee of Judiciary reports LB300, LB93, LB206, LB230, LB322, LB390, and LB579 to General File, some with committee amendments. Your Committee on Enrollment and Review reports LB224 and LB16 to Select File. That's all I have at this time, Mr. President. SCHEER: Thank you, Mr. Clerk. We'll proceed on to the first item on the agenda. ASSISTANT CLERK: Mr. President, LB399, introduced by Senator Slama. (Read title.) Bill was read for the first time on January 17 of this year. It was referred to the Education Committee. That committee reported the bill to General File with committee amendments. -

From African to African American: the Creolization of African Culture

From African to African American: The Creolization of African Culture Melvin A. Obey Community Services So long So far away Is Africa Not even memories alive Save those that songs Beat back into the blood... Beat out of blood with words sad-sung In strange un-Negro tongue So long So far away Is Africa -Langston Hughes, Free in a White Society INTRODUCTION When I started working in HISD’s Community Services my first assignment was working with inner city students that came to us straight from TYC (Texas Youth Commission). Many of these young secondary students had committed serious crimes, but at that time they were not treated as adults in the courts. Teaching these young students was a rewarding and enriching experience. You really had to be up close and personal with these students when dealing with emotional problems that would arise each day. Problems of anguish, sadness, low self-esteem, disappointment, loneliness, and of not being wanted or loved, were always present. The teacher had to administer to all of these needs, and in so doing got to know and understand the students. Each personality had to be addressed individually. Many of these students came from one parent homes, where the parent had to work and the student went unsupervised most of the time. In many instances, students were the victims of circumstances beyond their control, the problems of their homes and communities spilled over into academics. The teachers have to do all they can to advise and console, without getting involved to the extent that they lose their effectiveness. -

Martha's Vineyard Concert Series

THA’S VINEY AR ARD M SUMMER 2017 CONCERT SERIES 2ND ANNUAL SEASON ALL SHOWS ON SALE NOW! MVCONCERTSERIES.COM MARTHA’S VINEYARD CONCERT SERIES your year - round connection to Martha’s Vineyard SUmmER LINE-UP! JUNE 28 • AIMEE MANN over 6,500 photo, canvas WITH SPECIAL GUEST JONATHAN COULTON images & metal prints published agendas JULY 6 • LOUDON WAINWRIGHT III daily photos calendars JULY 13 • PINK MARTINI sent to your inbox notecards WITH LEAD SINGER CHINA FORBES JULY 18 • GRAHAM NASH JULY 23 • PRESERVATION HALL JAZZ BAND JULY 29 • JACKOPIERCE WITH SPECIAL GUEST IAN MURRAY FROM VINEYARD VINES AUGUST 15 • THE CAPITOL STEPS ALL NEW SHOW! ORANGE IS THE NEW BARACK AUGUST 19 • ARETHA FRANKLIN AUGUST 21 • DIRTY DOZEN BRAss BAND AUGUST 23 • BLACK VIOLIN GET YOUR TICKETS TODAY! www.vineyardcolors.com MVCONCERTSERIES.COM AIMEE MANN WITH SPECIAL GUEST JONATHON COULTON WEDNESDAY, JUNE 28 | MARTHA’S VINEYARD PAC Aimee Mann is an American rock singer-songwriter, bassist and guitarist. In 1983, she co-founded ‘Til Tuesday, a new-wave band that found success with its first album, Voices Carry. The title track became an MTV favorite, winning the MTV Video Music Award for Best New Artist, propelling Mann and the band into the spotlight. After releasing three albums with the group, she broke up the band and embarked on a solo career. Her first solo album, Whatever, was a more introspective, folk-tinged effort than ‘Til Tuesday’s albums, and received uniformly positive reviews upon its release in the summer of 1993. Mann’s song “Save Me” from the soundtrack to the Paul Thomas Anderson film Magnolia was nominated for an Academy® Award and a Grammy®. -

Fenomén K-Pop a Jeho Sociokulturní Kontexty Phenomenon K-Pop and Its

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI PEDAGOGICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra hudební výchovy Fenomén k-pop a jeho sociokulturní kontexty Phenomenon k-pop and its socio-cultural contexts Diplomová práce Autorka práce: Bc. Eliška Hlubinková Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Filip Krejčí, Ph.D. Olomouc 2020 Poděkování Upřímně děkuji vedoucímu práce Mgr. Filipu Krejčímu, Ph.D., za jeho odborné vedení při vypracovávání této diplomové práce. Dále si cením pomoci studentů Katedry asijských studií univerzity Palackého a členů české k-pop komunity, kteří mi pomohli se zpracováním tohoto tématu. Děkuji jim za jejich profesionální přístup, rady a celkovou pomoc s tímto tématem. Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně s použitím uvedené literatury a dalších informačních zdrojů. V Olomouci dne Podpis Anotace Práce se zabývá hudebním žánrem k-pop, historií jeho vzniku, umělci, jejich rozvojem, a celkovým vlivem žánru na společnost. Snaží se přiblížit tento styl, který obsahuje řadu hudebních, tanečních a kulturních směrů, široké veřejnosti. Mimo samotnou podobu a historii k-popu se práce věnuje i temným stránkám tohoto fenoménu. V závislosti na dostupnosti literárních a internetových zdrojů zpracovává historii žánru od jeho vzniku až do roku 2020, spolu s tvorbou a úspěchy jihokorejských umělců. Součástí práce je i zpracování dvou dotazníků. Jeden zpracovává názor české veřejnosti na k-pop, druhý byl mířený na českou k-pop komunitu a její myšlenky ohledně tohoto žánru. Abstract This master´s thesis is describing music genre k-pop, its history, artists and their own evolution, and impact of the genre on society. It is also trying to introduce this genre, full of diverse music, dance and culture movements, to the public. -

Filipino Americans and Polyculturalism in Seattle, Wa

FILIPINO AMERICANS AND POLYCULTURALISM IN SEATTLE, WA THROUGH HIP HOP AND SPOKEN WORD By STEPHEN ALAN BISCHOFF A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN AMERICAN STUDIES WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Department of American Studies DECEMBER 2008 To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the thesis of STEPHEN ALAN BISCHOFF find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. _____________________________________ Chair, Dr. John Streamas _____________________________________ Dr. Rory Ong _____________________________________ Dr. T.V. Reed ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Since I joined the American Studies Graduate Program, there has been a host of faculty that has really helped me to learn what it takes to be in this field. The one professor that has really guided my development has been Dr. John Streamas. By connecting me to different resources and his challenging the confines of higher education so that it can improve, he has been an inspiration to finish this work. It is also important that I mention the help that other faculty members have given me. I appreciate the assistance I received anytime that I needed it from Dr. T.V. Reed and Dr. Rory Ong. A person that has kept me on point with deadlines and requirements has been Jean Wiegand with the American Studies Department. She gave many reminders and explained answers to my questions often more than once. Debbie Brudie and Rose Smetana assisted me as well in times of need in the Comparative Ethnic Studies office. My cohort over the years in the American Studies program have developed my thinking and inspired me with their own insight and work. -

The Human Relationship with Our Ocean Planet

Commissioned by BLUE PAPER The Human Relationship with Our Ocean Planet LEAD AUTHORS Edward H. Allison, John Kurien and Yoshitaka Ota CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS: Dedi S. Adhuri, J. Maarten Bavinck, Andrés Cisneros-Montemayor, Michael Fabinyi, Svein Jentoft, Sallie Lau, Tabitha Grace Mallory, Ayodeji Olukoju, Ingrid van Putten, Natasha Stacey, Michelle Voyer and Nireka Weeratunge oceanpanel.org About the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy The High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy (Ocean Panel) is a unique initiative by 14 world leaders who are building momentum for a sustainable ocean economy in which effective protection, sustainable production and equitable prosperity go hand in hand. By enhancing humanity’s relationship with the ocean, bridging ocean health and wealth, working with diverse stakeholders and harnessing the latest knowledge, the Ocean Panel aims to facilitate a better, more resilient future for people and the planet. Established in September 2018, the Ocean Panel has been working with government, business, financial institutions, the science community and civil society to catalyse and scale bold, pragmatic solutions across policy, governance, technology and finance to ultimately develop an action agenda for transitioning to a sustainable ocean economy. Co-chaired by Norway and Palau, the Ocean Panel is the only ocean policy body made up of serving world leaders with the authority needed to trigger, amplify and accelerate action worldwide for ocean priorities. The Ocean Panel comprises members from Australia, Canada, Chile, Fiji, Ghana, Indonesia, Jamaica, Japan, Kenya, Mexico, Namibia, Norway, Palau and Portugal and is supported by the UN Secretary-General’s Special Envoy for the Ocean. -

PHILLIPS EXETER ACADEMY STUDENT CLUB and CAMPUS ORGANIZATION LISTING: 2017-2018 Academy Belly Dancing Society It Is the PEA Traditional Belly Dancing Team on Campus

PHILLIPS EXETER ACADEMY STUDENT CLUB AND CAMPUS ORGANIZATION LISTING: 2017-2018 Academy Belly Dancing Society It is the PEA traditional belly dancing team on campus. American Culture Club Boosting school spirit and community through tailgates and lawn games. Animal Rights Club A club devoted to discussing and taking action in animal rights and animal agriculture issues. We have a lot of ideas, and have already accomplished a lot over the past two years, such as hosting two Veg-Fests, holding a panel on Climate Action Day, and meeting with the biology teachers to ask for a dissection policy that would allow some students to have an alternative to dissections, which they just recently passed. During our club meeting, we hold discussions, plan our ideas and events, and write letters in support of animal rights related issues. Anime Club A club based around discussion, enjoyment, and recommendations of Japanese Animation. Animation Club Animation Club is a new club where students interested animation or art in general can work together to create and learn about animations. We will be working on both 2D and 3D animation. ArchitExeter Exeter's Architecture Club Association of Communist Exonians Come discuss capitalism, socialism, and communism over lunch. We invite capitalists, socialists, and communists of all stripes. Prominent speakers like Duke Professor Michael Hardt and Communist Party USA chairperson John Bachtell will be Skyping in to talk to us. ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) The club is a support group for students who identify with any of the countries in the real world ASEAN, which includes Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Viet Nam. -

The Policy of Multicultural Education in Russia: Focus on Personal Priorities

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL & SCIENCE EDUCATION 2016, VOL. 11, NO. 18, 12613-12628 OPEN ACCESS THE POLICY OF MULTICULTURAL EDUCATION IN RUSSIA: FOCUS ON PERSONAL PRIORITIES a a Natalya Yuryevna Sinyagina , Tatiana Yuryevna Rayfschnayder , a Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration, RUSSIA, ABSTRACT The article contains the results of the study of the current state of multicultural education in Russia. The history of studying the problem of multicultural education has been analyzed; an overview of scientific concepts and research of Russian scientists in the sphere of international relations, including those conducted under defended theses, and the description of technologies of multicultural education in Russia (review of experience, programs, curricula and their effectiveness) have been provided. The ways of the development of multicultural education in Russia have been described. Formulation of the problem of the development of multicultural education in the Russian Federation is currently associated with a progressive trend of the inter- ethnic and social differentiation, intolerance and intransigence, which are manifested both in individual behavior (adherence to prejudices, avoiding contacts with the "others", proneness to conflict) and in group actions (interpersonal aggression, discrimination on any grounds, ethnic conflicts, etc.). A negative attitude towards people with certain diseases, disabilities, HIV-infected people, etc., is another problem at the moment. This situation also