Rwanda, Burundi, and Their "Ethnic" Conflicts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Worst Place in the World to Be a Woman?: Women's Conflict

DePauw University Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University Student research Student Work 2016 The orsW t Place in the World to be a Woman?: Women's Conflict Experiences in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Megan Bailey DePauw University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.depauw.edu/studentresearch Part of the Peace and Conflict Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bailey, Megan, "The orW st Place in the World to be a Woman?: Women's Conflict Experiences in the Democratic Republic of the Congo" (2016). Student research. Paper 43. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student research by an authorized administrator of Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Worst Place in the World to be a Woman?: Women’s Conflict Experiences in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Megan Bailey Spring 2016 Prof. Brett O’Bannon (sponsor) Prof. Tamara Beauboeuf Tiamo Katsonga-Phiri 3 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my committee members for the constant support they have given me during the past two semesters. You’ve taken so much time out of your busy schedules to help me, and I couldn’t be more appreciative. A special thank you to Prof. Brett O’Bannon, for telling me that it’s okay to have feelings about difficult topics and that this work is most definitely important. To Prof. Tamara Beauboeuf, for always asking the hard questions and pushing this project to be the best it can be. -

Business Ethics As Field of Training, Teaching and Research in Francophone Africa

Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Original Business Ethics as field of training, teaching and Article research in Francophone Africa Liboire Kagabo Department of African Languages and Literature, University of Burundi, Burundi ABSTRACT This article has been written within the framework of the Global Survey of Business Ethics 2010. It is seemingly the first attempt to investigate Business Ethics as academic field in Francophone Africa. After a discussion of methodological considerations, the article provides an overview of how Business Ethics is distributed in Francophone Africa. Even though, it is not well established in that part of Africa, some interesting data have been found in some countries like Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ivory Coast, Rwanda and Senegal. Business Ethics has been investigated in three areas: teaching, training and research. In Francophone Africa, teaching Business Ethics does not seem to be a reality in traditional faculties of Economics, Management or Commerce. Training in Business Ethics, however, is a reality in Francophone Africa, notably with the non-governmental organizations that deal with political and economic governance, development, and women and gender issues. Research on Business Ethics can be found in journals, bulletins, consultancy reports, university term papers, seminars and colloquia as well as in books. Key words: Business Ethics, Teaching, Training, Research, Francophone Africa INTRODUCTION Madagascar. For the purpose of the survey some French speaking countries in West For the purpose of the Global Survey of Africa, namely Cameroun, Tchad, Niger, Business Ethics 2010, the world was divided Benin and Togo was however included in into nine world regions, one of which was the the West African region. -

Queer Theory, Ethno/Musicology, and the Disorientation of the Field

Queer Theory, Ethno/Musicology, and the Disorientation of the Field Steven Moon We spend significant time and space in our academic lives positioning ourselves: within the theory of the field, in regard to the institution, within networks of interlocutors, scholars, performers, and so on. We are likewise trained to critique those positions, to identify modes of power in their myriad manifestations, and to work towards more equitable methods and theory. That is, we constantly are subject to attempts of disciplinary orienta- tion, and constantly negotiate forms of re-orientation. Sara Ahmed reminds us that we might ask not only how we are oriented within our discipline, but also about 1) how the discipline itself is oriented, and 2) how orien- tation within sexuality shapes how our bodies extend into space (2006). This space—from disciplinary space, to performance space, to the space of fieldwork and the archive—is a boundless environment cut by the trails of the constant reorientation of those before us. But our options are more than the dichotomy between “be oriented” and “re-orient oneself.” In this essay, I examine the development of the ethno/musicologies’ (queer) theoretical borrowings from anthropology, sociology, and literary/cultural studies in order to historicize the contemporary queer moment both fields are expe- riencing and demonstrate the ways in which it might dis-orient the field. I trace the histories of this queer-ing trend by beginning with early concep- tualizations of the ethno/musicological projects, scientism, and quantita- tive methods. This is in relation to the anthropological method of ethno- cartography in order to understand the historical difficulties in creating a queer qualitative field, as opposed to those based in hermeneutics. -

Ituri:Stakes, Actors, Dynamics

ITURI STAKES, ACTORS, DYNAMICS FEWER/AIP/APFO/CSVR would like to stress that this report is based on the situation observed and information collected between March and August 2003, mainly in Ituri and Kinshasa. The 'current' situation therefore refers to the circumstances that prevailed as of August 2003, when the mission last visited the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the Swedish International Development Agency. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Swedish Government and its agencies. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the Department for Development Policy, Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Finnish Government and its agencies. Copyright 2003 © Africa Initiative Program (AIP) Africa Peace Forum (APFO) Centre for Study of Violence and Reconciliation (CSVR) Forum on Early Warning and Early Response (FEWER) The views expressed by participants in the workshop are not necessarily those held by the workshop organisers and can in no way be take to reflect the views of AIP, APFO, CSVR and FEWER as organisations. 2 List of Acronyms............................................................................................................................... 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...................................................................................................................................... -

IN SEARCH of Africa's Greatest Safaris

IN SEARCH of Africa's Greatest Safaris A S E R I E S O F L I F E C H A N G I N G J O U R N E Y S T H A T L E A V E A F R I C A ' S W I L D L I F E I N A B E T T E R P L A C E Who We Are Vayeni is owned and run by Luke & Suzanne Brown. Together they have built a formidable reputation for seeking out the finest safari experiences Africa can offer and combining these into cathartic experiences for the most judicious travellers. Luke and Suzanne also co- founded the Zambesia Conservation Alliance together with Luke's brother Robin. Through Zambesia their goal is to successfully assist Africa's increasingly threatened habitats and wildlife. Where We Take You East Africa Indian Ocean Islands Southern Africa Antarctica Comfort Between Destinations All journeys include a private jet between destinations & a dedicated, highly acclaimed African specialist guide throughout. CA AFRI EAST NDS ISLA CEAN AN O INDI ly p s e S e e E d d f i o R v a s U o . h r f e c S p o d i r A l t e r r a E c o a e e R n h w S t e S T d n S e i d y ' c v e T t e I la e c F p s e n I n s r R e n A l o u d c o n u J o re b atu ign S S OU T HE IND RN IA AF N R OC ICA ch of EA In Sear N ISL ICA AN T AFR DS EAS FRICA ERN A DS ECRETS UTH SLAN ZAMBESIA'S S SO EAN I N OC A INDIA CTIC NTAR A A vast & rich region of s, s, wildlife presided over by the o d of in r rgest African elephant herd 7 h pa s la ch R o le r T , e a on the planet. -

Burundi-SCD-Final-06212018.Pdf

Document of The World Bank Report No. 122549-BI Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF BURUNDI ADDRESSING FRAGILITY AND DEMOGRAPHIC CHALLENGES TO REDUCE POVERTY AND BOOST SUSTAINABLE GROWTH Public Disclosure Authorized SYSTEMATIC COUNTRY DIAGNOSTIC June 15, 2018 Public Disclosure Authorized International Development Association Country Department AFCW3 Africa Region International Finance Corporation (IFC) Sub-Saharan Africa Department Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) Sub-Saharan Africa Department Public Disclosure Authorized BURUNDI - GOVERNMENT FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective as of December 2016) Currency Unit = Burundi Franc (BIF) US$1.00 = BIF 1,677 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ACLED Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project AfDB African Development Bank BMM Burundi Musangati Mining CE Cereal Equivalent CFSVA Comprehensive Food Security and Vulnerability Assessment CNDD-FDD Conseil National Pour la Défense de la Démocratie-Forces pour la Défense de la Démocratie (National Council for the Defense of Democracy-Forces for the Defense of Democracy) CPI Consumer Price Index CPIA Country Policy and Institutional Assessment DHS Demographic and Health Survey EAC East African Community ECVMB Enquête sur les Conditions de Vie des Menages au Burundi (Survey on Household Living Conditions in Burundi) ENAB Enquête Nationale Agricole du Burundi (National Agricultural Survey of Burundi) FCS Fragile and conflict-affected situations FDI Foreign Direct Investment FNL Forces Nationales -

Burundi: the Issues at Stake

BURUNDI: THE ISSUES AT STAKE. POLITICAL PARTIES, FREEDOM OF THE PRESS AND POLITICAL PRISONERS 12 July 2000 ICG Africa Report N° 23 Nairobi/Brussels (Original Version in French) Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..........................................................................................i INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................1 I. POLITICAL PARTIES: PURGES, SPLITS AND CRACKDOWNS.........................1 A. Beneficiaries of democratisation turned participants in the civil war (1992-1996)3 1. Opposition groups with unclear identities ................................................. 4 2. Resorting to violence to gain or regain power........................................... 7 B. Since the putsch: dangerous games of the government................................... 9 1. Purge of opponents to the peace process (1996-1998)............................ 10 2. Harassment of militant activities ............................................................ 14 C. Institutionalisation of political opportunism................................................... 17 1. Partisan putsches and alliances of convenience....................................... 18 2. Absence of fresh political attitudes......................................................... 20 D. Conclusion ................................................................................................. 23 II WHICH FREEDOM FOR WHAT MEDIA ?...................................................... 25 A. Media -

ARMING RWANDA the Arms Trade and Human Rights Abuses in the Rwandan War

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH ARMS PROJECT January 1994 Vol. 6, Issue 1 ARMING RWANDA The Arms Trade and Human Rights Abuses in the Rwandan War Contents MapMap...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 IntroductionIntroduction....................................................................................................................................................................................4 Summary of Key Findings ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 Summary of Recommendations .......................................................................................................................................... 6 I. Historical Background to the WarWar......................................................................................................................................7 The Banyarwanda and Uganda..............................................................................................................................................7 Rwanda and the Habyarimana Regime............................................................................................................................ 9 II. The Record on Human RightsRights..............................................................................................................................................11 -

The International Response to Conflict and Genocide:Lessom from the Rwanda Experience

The International Response to Conflict and Genocide: Lessons from the Rwanda Experience March 1996 Published by: Steering Committee of the Joint Evaluation of Emergency Assistance to Rwanda Editor: David Millwood Cover illustrations: Kiure F. Msangi Graphic design: Designgrafik, Copenhagen Prepress: Dansk Klich‚, Copenhagen Printing: Strandberg Grafisk, Odense ISBN: 87-7265-335-3 (Synthesis Report) ISBN: 87-7265-331-0 (1. Historical Perspective: Some Explanatory Factors) ISBN: 87-7265-332-9 (2. Early Warning and Conflict Management) ISBN: 87-7265-333-7 (3. Humanitarian Aid and Effects) ISBN: 87-7265-334-5 (4. Rebuilding Post-War Rwanda) This publication may be reproduced for free distribution and may be quoted provided the source - Joint Evaluation of Emergency Assistance to Rwanda - is mentioned. The report is printed on G-print Matt, a wood-free, medium-coated paper. G-print is manufactured without the use of chlorine and marked with the Nordic Swan, licence-no. 304 022. 2 The International Response to Conflict and Genocide: Lessons from the Rwanda Experience Study 2 Early Warning and Conflict Management by Howard Adelman York University Toronto, Canada Astri Suhrke Chr. Michelsen Institute Bergen, Norway with contributions by Bruce Jones London School of Economics, U.K. Joint Evaluation of Emergency Assistance to Rwanda 3 Contents Preface 5 Executive Summary 8 Acknowledgements 11 Introduction 12 Chapter 1: The Festering Refugee Problem 17 Chapter 2: Civil War, Civil Violence and International Response 20 (1 October 1990 - 4 August -

The Rwandan Genocide: Combating Stereotypes And

The Rwandan Genocide: Combating Stereotypes and Understanding the Origins Nicola Skakel Senior Honors Thesis Department of History April 9th 2018 Defense Committee: Dr. Susan K. Kent, Department of History, Primary Advisor Dr. Matthew Gerber, Department of History, Honors Council Representative Dr. Paul Shankman, Department of Anthropology, Advisor 1 Introduction On the 7th of April 1994, the small east African country of Rwanda erupted into one of the most deadly and intimate genocides the modern world had ever witnessed. Whilst the western world stood by and watched in just 100 days over 800,000 Rwandans out of a total population of 7 million, were systematically murdered in the most brutal and violent of ways. Those who were targeted made up the country’s minority ethnic group the Tutsis, and moderates from the majority group, the Hutus. For many, the legacy of Rwanda is a monstrous example of extreme pent up ethnic tensions that has its roots in European colonialism. In contrast, I will argue that the events not just of 1994 but also the unrest that proceeded it, arose from a highly complex culmination of long-standing historical tensions between ethnic groups that long pre-dated colonialism. In conjunction, a set of short-term triggers including foreign intervention, civil war, famine, state terrorism and ultimately the assassination of President Habyarimana also contributed to the outburst of genocide in 1994. Whilst it would be easy to place sole responsibility on European colonists for implementing a policy of divide and rule and therefore exacerbating ethnic tensions, it seems to me that genocide is never that cut and dried: it can never be explained by one factor. -

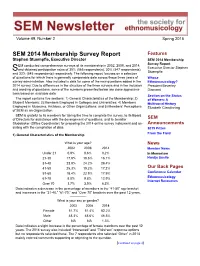

SEM 2014 Membership Survey Report Features Stephen Stuempfle, Executive Director SEM 2014 Membership

Volume 49, Number 2 Spring 2015 SEM 2014 Membership Survey Report Features Stephen Stuempfle, Executive Director SEM 2014 Membership EM conducted comprehensive surveys of its membership in 2002, 2008, and 2014, Survey Report Executive Director Stephen and obtained participation rates of 35% (565 respondents), 30% (547 respondents), S Stuempfle and 32% (545 respondents) respectively. The following report focuses on a selection of questions for which there is generally comparable data across these three years of Whose survey administration. Also included is data for some of the new questions added in the Ethnomusicology? 2014 survey. Due to differences in the structure of the three surveys and in the inclusion President Beverley and wording of questions, some of the numbers presented below are close approxima- Diamond tions based on available data. Section on the Status The report contains five sections: 1) General Characteristics of the Membership; 2) of Women: A Student Members; 3) Members Employed in Colleges and Universities; 4) Members Multivocal History Employed in Museums, Archives, or Other Organizations; and 5) Members’ Perceptions Elizabeth Clendinning of SEM as an Organization. SEM is grateful to its members for taking the time to complete the survey, to its Board of Directors for assistance with the development of questions, and to Jennifer SEM Studebaker (Office Coordinator) for preparing the 2014 online survey instrument and as- Announcements sisting with the compilation of data. 2015 Prizes From the Field 1) General Characteristics of the Membership What is your age? News 2002 2008 2014 Member News Under 21 0.9% 0.6% 0.2% In Memoriam 21-30 17.9% 19.6% 16.1% Hardja Susilo 31-40 23.9% 24.2% 29.4% 41-50 25.3% 19.2% 17.2% Our Back Pages 51-60 18.4% 22.9% 17.9% Conference Calendar 61-70 8.0% 9.8% 12.9% Ethnomusicology Internet Resources Over 70 3.7% 3.9% 6.3% Data indicates a decrease in the percentage of members in the “41-50” age bracket and increases in the “31-40,” “61-70,” and “Over 70” brackets over the past 12 years. -

HIV DR in CENTRAL AFRICA

WHO HIVRESNET STEERING COMMITTEE MEETING, November 10–12, 2009, Geneva, Switzerland HIV DR in CENTRAL AFRICA Pr Belabbes Intercountry Support Team Central Africa COUNTRIES COVERED BY THE INTERCOUNTRY SUPPORT TEAM / CENTRAL AFRICA Angola Burundi Cameroon Central African Republic Chad Congo Democratic Republic of Congo Equatorial Guinea Gabon Rwanda Sao Tome & Principe HIV PREVALENCE AMONG THE POPULATION Legend Generalized epidemic in 10 <1% countries /11 1-5% >5% Excepted Sao Tome& Principe nd HIV PREVALENCE AMONG PREGNANT WOMEN Legend <1% 1-5% >5% nd PATIENTS UNDER ART 2005-2008 70000 2005 2006 2007 2008 60000 50000 40000 30000 20000 10000 0 Angola Burundi Cameroon Congo Equatorial Gabon CAR DRC Rwanda Sao Tome Guinea Source of data Towards universal access: scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector. WHO, UNAIDS,UNICEF;September 2009. Training on HIVDR Protocols ANGOLA BURUNDI CAMEROON CENTRAL AFRICA REPUBLIC CHAD CONGO DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC CONGO EQUATORIAL GUINEA GABON RWANDA SAO TOME&PRINCIPE Training on HIVDR Protocols Douala, Cameroon 27-29 April 2009 The opening ceremony Participants to the Training on HIVDR Protocols, Douala Cameroon 27-29 April 2009 ON SITE STRENGTHENING CAPACITIES OF THE TECHNICAL WORKING GROUPS ANGOLA BURUNDI CAMEROON CENTRAL AFRICA REPUBLIC CHAD EQUATORIAL GUINEA RWANDA TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PROVIDED TO DEVELOP HIVDR PROTOCOLS ANGOLA BURUNDI CAMEROON CENTRAL AFRICA REPUBLIC CHAD EQUATORIAL GUINEA RWANDA EARLY WARNING INDICATORS BURUNDI : EWI abstraction in 19 sites (October) using paper-based.