Ituri:Stakes, Actors, Dynamics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Worst Place in the World to Be a Woman?: Women's Conflict

DePauw University Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University Student research Student Work 2016 The orsW t Place in the World to be a Woman?: Women's Conflict Experiences in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Megan Bailey DePauw University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.depauw.edu/studentresearch Part of the Peace and Conflict Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bailey, Megan, "The orW st Place in the World to be a Woman?: Women's Conflict Experiences in the Democratic Republic of the Congo" (2016). Student research. Paper 43. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student research by an authorized administrator of Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Worst Place in the World to be a Woman?: Women’s Conflict Experiences in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Megan Bailey Spring 2016 Prof. Brett O’Bannon (sponsor) Prof. Tamara Beauboeuf Tiamo Katsonga-Phiri 3 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my committee members for the constant support they have given me during the past two semesters. You’ve taken so much time out of your busy schedules to help me, and I couldn’t be more appreciative. A special thank you to Prof. Brett O’Bannon, for telling me that it’s okay to have feelings about difficult topics and that this work is most definitely important. To Prof. Tamara Beauboeuf, for always asking the hard questions and pushing this project to be the best it can be. -

Addressing Root Causes of Conflict: a Case Study Of

Experience paper Addressing root causes of conflict: A case study of the International Security and Stabilization Support Strategy and the Patriotic Resistance Front of Ituri (FRPI) in Ituri Province, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo Oslo, May 2019 1 About the Author: Ingebjørg Finnbakk has been deployed by the Norwegian Resource Bank for Democracy and Human Rights (NORDEM) to the Stabilization Support Unit (SSU) in MONUSCO from August 2016 until February 2019. Together with SSU Headquarters and Congolese partners she has been a key actor in developing and implementing the ISSSS program in Ituri Province, leading to a joint MONUSCO and Government process and strategy aimed at demobilizing a 20-year-old armed group in Ituri, the Patriotic Resistance Front of Ituri (FRPI). The views expressed in this report are her own, and do not represent those of either the UN or the Norwegian Refugee Council/NORDEM. About NORDEM: The Norwegian Resource Bank for Democracy and Human Rights (NORDEM) is NORCAP’s civilian capacity provider specializing in human rights and support for democracy. NORDEM has supported the SSU with personnel since 2013, hence contribution significantly with staff through the various preparatory phases as well as during the implementation. Acknowledgements: Reaching the point of implementing ISSSS phase two programs has required a lot of analyses, planning and stakeholder engagement. The work presented in this report would not be possible without all the efforts of previous SSU staff under the leadership of Richard de La Falaise. The FRPI process would not have been possible without the support and visions from Francois van Lierde (deployed by NORDEM) and Frances Charles at SSU HQ level. -

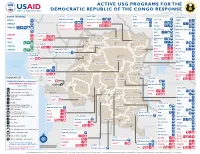

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS for the DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20 BAS-UELE HAUT-UELE ITURI S O U T H S U D A N COUNTRYWIDE NORTH KIVU OCHA IMA World Health Samaritan’s Purse AIRD Internews CARE C.A.R. Samaritan’s Purse Samaritan’s Purse IMA World Health IOM UNHAS CAMEROON DCA ACTED WFP INSO Medair FHI 360 UNICEF Samaritan’s Purse Mercy Corps IMA World Health NRC NORD-UBANGI IMC UNICEF Gbadolite Oxfam ACTED INSO NORD-UBANGI Samaritan’s WFP WFP Gemena BAS-UELE Internews HAUT-UELE Purse ICRC Buta SCF IOM SUD-UBANGI SUD-UBANGI UNHAS MONGALA Isiro Tearfund IRC WFP Lisala ACF Medair UNHCR MONGALA ITURI U Bunia Mercy Corps Mercy Corps IMA World Health G A EQUATEUR Samaritan’s NRC EQUATEUR Kisangani N Purse WFP D WFPaa Oxfam Boende A REPUBLIC OF Mbandaka TSHOPO Samaritan’s ATLANTIC NORTH GABON THE CONGO TSHUAPA Purse TSHOPO KIVU Lake OCEAN Tearfund IMA World Health Goma Victoria Inongo WHH Samaritan’s Purse RWANDA Mercy Corps BURUNDI Samaritan’s Purse MAI-NDOMBE Kindu Bukavu Samaritan’s Purse PROGRAM KEY KINSHASA SOUTH MANIEMA SANKURU MANIEMA KIVU WFP USAID/BHA Non-Food Assistance* WFP ACTED USAID/BHA Food Assistance** SA ! A IMA World Health TA N Z A N I A Kinshasa SH State/PRM KIN KASAÏ Lusambo KWILU Oxfam Kenge TANGANYIKA Agriculture and Food Security KONGO CENTRAL Kananga ACTED CRS Cash Transfers For Food Matadi LOMAMI Kalemie KASAÏ- Kabinda WFP Concern Economic Recovery and Market Tshikapa ORIENTAL Systems KWANGO Mbuji T IMA World Health KWANGO Mayi TANGANYIKA a KASAÏ- n Food Vouchers g WFP a n IMC CENTRAL y i k -

Justice - Plus

JUSTICE - PLUS PANEL OF RESEARCH ON THE PROLIFERATION AND ILLICIT TRAFFIC OF SMALL ARMS AND LIGHT WEAPONS IN THE FRONTIER AREAS BETWEEN SUDAN, UGANDA AND THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO PROLIFERATION AND ILLICIT TRAFFIC OF SMALL ARMS AND LIGHT WEAPONS IN THE NORTH EAST OF THE DRC Summary Report by Flory KAYEMBE SHAMBA Désiré NKOY ELELA Missak KASONGO MUZEU Kinshasa, January 2003 JUSTICE-PLUS • BUNIA • KINSHASA Siège social Bureau de liaison 39bis, Av. KASAVUBU,Q. Lumumba 3, Av. KITONA, Q. Righini, C/Lemba B.P 630-BUNIA B.P. 2063 Kinshasa 1 Tél. : (+) 871762568941 tél. : (+)243 98171 100 Fax : (+)871762568943 Fax : (+) 243 8801826 E-mail : [email protected] E-mail : [email protected] research on the proliferation and illicit traffic of small arms and light weapons in the north east of the drc – flodémis 1 _______________________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS INITIALS……..…………………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………….……………………………………………………………… 3 INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………………………………. 4 I. CONCEPTUAL AND METHODOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK …………………………..………….. 6 TERMES DE REFERENCE……………………………………………………………………… 6 METHODOLOGY AND UNFOLDING OF THE RESEARCH……………………………. 9 II. OUTLINE OF THE SITUATION IN THE NORTH EAST OF THE DRC ………………….. 10 MAPPING OF CONFLITS IN ITURI AND UPPER UELE (Alliances and counter-alliances)…………………………………………………………..…….. 12 III. PRESENTATION OF DATE BY INVESTIGATION CENTRE………………………………… 13 IV. SUMMARY OF RESEARCH FINDINGS ……………………..……………………………….… 14 4.1. GENERAL PERCEPTION OF THE CONFLITS ……………………………………... 14 4.2. SMALL ARMS AND LIGHT WEAPONS : CIRCUITS OF ACQUISITION, COST, SOURCES OF SUPPLY, COMMERCIAL FLOW, IMPORTANCE …………………………………………………………………………….. 17 4.3. CONTROL OF THE CIRCULATION OF SMALL ARMS & LIGHT WEAPONS AND PROSPECTS FOR PEACE IN AFRICA’S GREAT LAKES REGION …………… 20 4.4. VERIFICATION OF RESEARCH HYPOTHESES ……………………………..…… 23 V. STRATEGIES OF FIGHT AND RECOMMENDATIONS ………………………………………… 26 5.1. -

The Rwandan Genocide: Combating Stereotypes And

The Rwandan Genocide: Combating Stereotypes and Understanding the Origins Nicola Skakel Senior Honors Thesis Department of History April 9th 2018 Defense Committee: Dr. Susan K. Kent, Department of History, Primary Advisor Dr. Matthew Gerber, Department of History, Honors Council Representative Dr. Paul Shankman, Department of Anthropology, Advisor 1 Introduction On the 7th of April 1994, the small east African country of Rwanda erupted into one of the most deadly and intimate genocides the modern world had ever witnessed. Whilst the western world stood by and watched in just 100 days over 800,000 Rwandans out of a total population of 7 million, were systematically murdered in the most brutal and violent of ways. Those who were targeted made up the country’s minority ethnic group the Tutsis, and moderates from the majority group, the Hutus. For many, the legacy of Rwanda is a monstrous example of extreme pent up ethnic tensions that has its roots in European colonialism. In contrast, I will argue that the events not just of 1994 but also the unrest that proceeded it, arose from a highly complex culmination of long-standing historical tensions between ethnic groups that long pre-dated colonialism. In conjunction, a set of short-term triggers including foreign intervention, civil war, famine, state terrorism and ultimately the assassination of President Habyarimana also contributed to the outburst of genocide in 1994. Whilst it would be easy to place sole responsibility on European colonists for implementing a policy of divide and rule and therefore exacerbating ethnic tensions, it seems to me that genocide is never that cut and dried: it can never be explained by one factor. -

Democratic Republic of Congo Democratic Republic of Congo Gis Unit, Monuc Africa

Map No.SP. 103 ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO GIS UNIT, MONUC AFRICA 12°30'0"E 15°0'0"E 17°30'0"E 20°0'0"E 22°30'0"E 25°0'0"E 27°30'0"E 30°0'0"E Central African Republic N N " " 0 0 ' Sudan ' 0 0 ° ° 5 5 Z o n g oBangui Mobayi Bosobolo Gbadolite Yakoma Ango Yaounde Bondo Nord Ubangi Niangara Faradje Cameroon Libenge Bas Uele Dungu Bambesa Businga G e m e n a Haut Uele Poko Rungu Watsa Sud Ubangi Aru Aketi B u tt a II s ii rr o r e Kungu Budjala v N i N " R " 0 0 ' i ' g 0 n 0 3 a 3 ° b Mahagi ° 2 U L ii s a ll a Bumba Wamba 2 Orientale Mongala Co Djugu ng o R i Makanza v Banalia B u n ii a Lake Albert Bongandanga er Irumu Bomongo MambasaIturi B a s a n k u s u Basoko Yahuma Bafwasende Equateur Isangi Djolu Yangambi K i s a n g a n i Bolomba Befale Tshopa K i s a n g a n i Beni Uganda M b a n d a k a N N " Equateur " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Lubero ° 0 Ingende B o e n d e 0 Gabon Ubundu Lake Edward Opala Bikoro Bokungu Lubutu North Kivu Congo Tshuapa Lukolela Ikela Rutshuru Kiri Punia Walikale Masisi Monkoto G o m a Yumbi II n o n g o Kigali Bolobo Lake Kivu Rwanda Lomela Kalehe S S " KabareB u k a v u " 0 0 ' ' 0 Kailo Walungu 0 3 3 ° Shabunda ° 2 2 Mai Ndombe K ii n d u Mushie Mwenga Kwamouth Maniema Pangi B a n d u n d u Bujumbura Oshwe Katako-Kombe South Kivu Uvira Dekese Kole Sankuru Burundi Kas ai R Bagata iver Kibombo Brazzaville Ilebo Fizi Kinshasa Kasongo KasanguluKinshasa Bandundu Bulungu Kasai Oriental Kabambare K e n g e Mweka Lubefu S Luozi L u s a m b o S " Tshela Madimba Kwilu Kasai -

Reporting Principles

COMMON SECURITY AND DEFENCE POLICY EU BATTLEGROUPS Updated: January 2011 Battllegroups/07 Full operational capability in 2007 The European Union is a global actor, ready to undertake its share of responsibility for global security. With the introduction of the battlegroup concept, the Union formed a (further) military instrument at its disposal for early and rapid responses, when necessary. On 1 January 2007 the EU battlegroup concept reached full operational capability. Since that date, the EU is able to undertake, if so decided by the Council, two concurrent single-battlegroup-sized (about 1 500-strong) rapid response operations, including the ability to launch both operations nearly simultaneously. At the 1999 Helsinki European Council meeting, rapid response was identified as an important aspect of crisis management. As a result, the Helsinki Headline Goal 2003 assigned to member states the objective of being able to provide rapid response elements available and deployable at very high levels of readiness. Subsequently, an EU military rapid response concept was developed. In June 2003 the first autonomous EU-led military operation, Operation Artemis, was launched. It showed very successfully the EU's ability to operate with a rather small force at a significant distance from Brussels, in this case more than 6 000 km. Moreover, it also demonstrated the need for further development of rapid response capabilities. Subsequently, Operation Artemis became a reference model for the development of a battlegroup-sized rapid response capability. In 2004 the Headline Goal 2010 aimed for completion of the development of rapidly deployable battlegroups, including the identification of appropriate strategic lift, sustainability and disembarkation assets, by 2007. -

UNHAS DRC Weekly Flight Schedule

UNHAS DRC Weekly Flight Schedule Effective from 09th June 2021 AIRCRAFT MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY KINSHASA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:00 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:30 08:30 KINSHASA BRAZZAVILLE 08:45 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:30 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:30 UNO-234H 09:30 MBANDAKA GBADOLITE 10:55 10:00 MBANDAKA YAKOMA 11:40 09:30 BRAZZAVILLE MBANDAKA 11:00 10:00 MBANDAKA GBADOLITE 11:25 10:00 MBANDAKA LIBENGE 11:00 5Y-VVI 11:25 GBADOLITE BANGUI 12:10 12:10 YAKOMA MBANDAKA 13:50 11:30 MBANDAKA IMPFONDO 12:00 11:55 GBADOLITE MBANDAKA 13:20 11:30 LIBENGE BANGUI 11:50 DHC-8-Q400 13:00 BANGUI MBANDAKA 14:20 14:20 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 15:50 12:30 IMPFONDO MBANDAKA 13:00 13:50 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 15:20 12:40 BANGUI MBANDAKA 14:00 SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE 14:50 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 16:20 13:30 MBANDAKA BRAZZAVILLE 15:00 14:30 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 16:00 15:30 BRAZZAVILLE KINSHASA 15:45 AD HOC CARGO FLIGHT TSA WITH UNHCR KINSHASA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA 09:00 KINSHASA KANANGA 11:15 08:00 KINSHASA KALEMIE 11:15 09:00 KINSHASA KANANGA 11:15 UNO-207H 11:45 KANANGA GOMA 13:10 11:45 KALEMIE GOMA 12:35 11:45 KANANGA GOMA 13:10 5Y-CRZ SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE EMB-145 LR 14:10 GOMA KANANGA 15:35 13:35 GOMA KINSHASA 14:50 14:10 GOMA KANANGA 15:35 16:05 KANANGA KINSHASA 16:20 16:05 KANANGA KINSHASA 16:20 -

Finnish Defence Forces International Centre the Many Faces of Military

Finnish Defence Forces International Finnish Defence Forces Centre 2 The Many Faces of Military Crisis Management Lessons from the Field Edited by Mikaeli Langinvainio Finnish Defence Forces FINCENT Publication Series International Centre 1:2011 1 FINNISH DEFENCE FORCES INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FINCENT PUBLICATION SERIES 1:2011 The Many Faces of Military Crisis Management Lessons from the Field EDITED BY MIKAELI LANGINVAINIO FINNISH DEFENCE FORCES INTERNATIONAL CENTRE TUUSULA 2011 2 Mikaeli Langinvainio (ed.): The Many Faces of Military Crisis Management Lessons from the Field Finnish Defence Forces International Centre FINCENT Publication Series 1:2011 Cover design: Harri Larinen Layout: Heidi Paananen/TKKK Copyright: Puolustusvoimat, Puolustusvoimien Kansainvälinen Keskus ISBN 978–951–25–2257–6 ISBN 978–951–25–2258–3 (PDF) ISSN 1797–8629 Printed in Finland Juvenens Print Oy Tampere 2011 3 Contents Jukka Tuononen Preface .............................................................................................5 Mikaeli Langinvainio Introduction .....................................................................................8 Mikko Laakkonen Military Crisis Management in the Next Decade (2020–2030) ..............................................................12 Antti Häikiö New Military and Civilian Training - What can they learn from each other? What should they learn together? And what must both learn? .....................................................................................20 Petteri Kurkinen Concept for the PfP Training -

Civil–Military Relations in Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo: a Case Study on Crisis Management in Complex Emergencies

Chapter 19 Civil–Military Relations in Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo: A Case Study on Crisis Management in Complex Emergencies Gudrun Van Pottelbergh The humanitarian crisis in Kivu in the Democratic Republic of Congo deteriorated again in the second half of 2008. In reaction, the international community agreed to send additional peacekeepers to stabilize the region. Supporters of the Congolese peace process agree that a military reaction alone will however not be sufficient. A stable future of the region requires a combined civil and military approach. This will also necessitate the continuous support of the international community for the Congolese peace process. The European Union and the United States are the two main players in terms of providing disaster management and thus also in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The European Union in particular has set- up several crisis management operations in the country. For the purpose of an efficient and combined effort in disaster relief, this study will investigate how different or similar these two players are in terms of crisis management mechanisms. The chapter concludes that the development of new crisis management mechanisms and the requirements for a sustainable solution in Kivu create an opportunity for all stakeholders described. Through establishing a high- level dialogue, the European Union and the United States could come up with a joint strategic and long- term approach covering all of their instru- ments in place to support the security reform in Kivu. It is especially in this niche of civilian and military cooperation within crisis management operations that may lay a key to finally bring peace and stability in the East of the Democratic Republic of Congo. -

Sample Chapter

Copyright material – 9781137025746 Contents List of Figures, Tables and Boxes viii Preface to the Second Edition x List of Abbreviations xii Introduction 1 Scope, Rationale and Relevance of the Book 1 The Changing Context of EU Foreign Policy 4 Objectives and Approach 6 Outline of Chapters 6 1 The Nature of EU Foreign Policy 11 Understanding EU Foreign Policy 11 Areas of Tension in EU Foreign Policy 19 Back to the Treaties: Principles and Objectives 25 Relational and Structural Foreign Policy 27 The Globalizing Context of EU Foreign Policy 30 Conclusion 33 2 European Integration and Foreign Policy: Historical Overview 35 European Integration: The Product of a Structural Foreign Policy (1945–52) 35 The First Decades (1952–70): A Taboo on Defence, Decisive Steps on Trade and International Agreements 39 European Political Cooperation: Setting the Stage (1970–93) 42 The Maastricht Treaty (1993) and the Illusory CFSP 46 The Amsterdam Treaty (1999) and ESDP: Moving towards Action 51 Eastern Enlargement (2004/07), the Lisbon Treaty (2009) and New Challenges 55 Conclusion 60 3 The EU’s Foreign Policy System: Actors 61 One Framework, Two Policy-making Methods, or a Continuum? 61 The European Council 63 The Council 66 The Commission 72 The High Representative/Vice-President and the EEAS 77 The European Parliament 85 v Copyright material – 9781137025746 vi Contents The Court of Justice 89 Other Actors 90 Conclusion 93 4 The EU’s Foreign Policy System: Policy-making 94 Competences 94 Decision-making 97 Policy-making in Practice 104 Financing EU Foreign -

Policy Briefs

Rethinking EU Crisis Management From Battlegroups to a European Legion? Niklas Nováky Summary June 2020 This paper discusses an idea to create a European Legion that has been put forward by Radoslaw Sikorski, MEP. This would be a new kind of EU military unit, made up of volunteers rather than national contingents contributed by the member states. The idea stems from Sikorski’s desire to reform the EU’s existing battlegroups, which have been operational for 15 years but have never been used, despite numerous opportunities. The paper argues that although the EU’s 2007 Lisbon Treaty imposes heavy restrictions on the Union’s ability to deploy military force, it does not rule out conducting operations with a volunteer force. At the same time, a volunteer-based European Legion force would have to be created initially by a group of member states outside the EU framework. These states could then make it available to the EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy as, for example, a permanent battlegroup. An existing model would be the multinational Eurocorps. Keywords CSDP – Crisis management – Battlegroups – European Legion – European Council – Eurocorps 1 Introduction Since the EU’s Common (formerly European) Security and Defence Policy (ESDP/CSDP) became operational in 2003, the Union has launched a total of 13 military operations within its framework. Of these, eight have been executive in character, meaning that they were authorised to use force if this had been deemed necessary to fulfil their mandate. The most recent CSDP military operation is Operation IRINI in the Mediterranean, which the EU launched on 31 March 2020 to help enforce the UN’s arms embargo on Libya.