Justice Strategy for Bunia-DRC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ituri:Stakes, Actors, Dynamics

ITURI STAKES, ACTORS, DYNAMICS FEWER/AIP/APFO/CSVR would like to stress that this report is based on the situation observed and information collected between March and August 2003, mainly in Ituri and Kinshasa. The 'current' situation therefore refers to the circumstances that prevailed as of August 2003, when the mission last visited the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the Swedish International Development Agency. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Swedish Government and its agencies. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the Department for Development Policy, Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Finnish Government and its agencies. Copyright 2003 © Africa Initiative Program (AIP) Africa Peace Forum (APFO) Centre for Study of Violence and Reconciliation (CSVR) Forum on Early Warning and Early Response (FEWER) The views expressed by participants in the workshop are not necessarily those held by the workshop organisers and can in no way be take to reflect the views of AIP, APFO, CSVR and FEWER as organisations. 2 List of Acronyms............................................................................................................................... 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...................................................................................................................................... -

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS for the DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20 BAS-UELE HAUT-UELE ITURI S O U T H S U D A N COUNTRYWIDE NORTH KIVU OCHA IMA World Health Samaritan’s Purse AIRD Internews CARE C.A.R. Samaritan’s Purse Samaritan’s Purse IMA World Health IOM UNHAS CAMEROON DCA ACTED WFP INSO Medair FHI 360 UNICEF Samaritan’s Purse Mercy Corps IMA World Health NRC NORD-UBANGI IMC UNICEF Gbadolite Oxfam ACTED INSO NORD-UBANGI Samaritan’s WFP WFP Gemena BAS-UELE Internews HAUT-UELE Purse ICRC Buta SCF IOM SUD-UBANGI SUD-UBANGI UNHAS MONGALA Isiro Tearfund IRC WFP Lisala ACF Medair UNHCR MONGALA ITURI U Bunia Mercy Corps Mercy Corps IMA World Health G A EQUATEUR Samaritan’s NRC EQUATEUR Kisangani N Purse WFP D WFPaa Oxfam Boende A REPUBLIC OF Mbandaka TSHOPO Samaritan’s ATLANTIC NORTH GABON THE CONGO TSHUAPA Purse TSHOPO KIVU Lake OCEAN Tearfund IMA World Health Goma Victoria Inongo WHH Samaritan’s Purse RWANDA Mercy Corps BURUNDI Samaritan’s Purse MAI-NDOMBE Kindu Bukavu Samaritan’s Purse PROGRAM KEY KINSHASA SOUTH MANIEMA SANKURU MANIEMA KIVU WFP USAID/BHA Non-Food Assistance* WFP ACTED USAID/BHA Food Assistance** SA ! A IMA World Health TA N Z A N I A Kinshasa SH State/PRM KIN KASAÏ Lusambo KWILU Oxfam Kenge TANGANYIKA Agriculture and Food Security KONGO CENTRAL Kananga ACTED CRS Cash Transfers For Food Matadi LOMAMI Kalemie KASAÏ- Kabinda WFP Concern Economic Recovery and Market Tshikapa ORIENTAL Systems KWANGO Mbuji T IMA World Health KWANGO Mayi TANGANYIKA a KASAÏ- n Food Vouchers g WFP a n IMC CENTRAL y i k -

Justice - Plus

JUSTICE - PLUS PANEL OF RESEARCH ON THE PROLIFERATION AND ILLICIT TRAFFIC OF SMALL ARMS AND LIGHT WEAPONS IN THE FRONTIER AREAS BETWEEN SUDAN, UGANDA AND THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO PROLIFERATION AND ILLICIT TRAFFIC OF SMALL ARMS AND LIGHT WEAPONS IN THE NORTH EAST OF THE DRC Summary Report by Flory KAYEMBE SHAMBA Désiré NKOY ELELA Missak KASONGO MUZEU Kinshasa, January 2003 JUSTICE-PLUS • BUNIA • KINSHASA Siège social Bureau de liaison 39bis, Av. KASAVUBU,Q. Lumumba 3, Av. KITONA, Q. Righini, C/Lemba B.P 630-BUNIA B.P. 2063 Kinshasa 1 Tél. : (+) 871762568941 tél. : (+)243 98171 100 Fax : (+)871762568943 Fax : (+) 243 8801826 E-mail : [email protected] E-mail : [email protected] research on the proliferation and illicit traffic of small arms and light weapons in the north east of the drc – flodémis 1 _______________________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS INITIALS……..…………………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………….……………………………………………………………… 3 INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………………………………. 4 I. CONCEPTUAL AND METHODOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK …………………………..………….. 6 TERMES DE REFERENCE……………………………………………………………………… 6 METHODOLOGY AND UNFOLDING OF THE RESEARCH……………………………. 9 II. OUTLINE OF THE SITUATION IN THE NORTH EAST OF THE DRC ………………….. 10 MAPPING OF CONFLITS IN ITURI AND UPPER UELE (Alliances and counter-alliances)…………………………………………………………..…….. 12 III. PRESENTATION OF DATE BY INVESTIGATION CENTRE………………………………… 13 IV. SUMMARY OF RESEARCH FINDINGS ……………………..……………………………….… 14 4.1. GENERAL PERCEPTION OF THE CONFLITS ……………………………………... 14 4.2. SMALL ARMS AND LIGHT WEAPONS : CIRCUITS OF ACQUISITION, COST, SOURCES OF SUPPLY, COMMERCIAL FLOW, IMPORTANCE …………………………………………………………………………….. 17 4.3. CONTROL OF THE CIRCULATION OF SMALL ARMS & LIGHT WEAPONS AND PROSPECTS FOR PEACE IN AFRICA’S GREAT LAKES REGION …………… 20 4.4. VERIFICATION OF RESEARCH HYPOTHESES ……………………………..…… 23 V. STRATEGIES OF FIGHT AND RECOMMENDATIONS ………………………………………… 26 5.1. -

Democratic Republic of Congo Democratic Republic of Congo Gis Unit, Monuc Africa

Map No.SP. 103 ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO GIS UNIT, MONUC AFRICA 12°30'0"E 15°0'0"E 17°30'0"E 20°0'0"E 22°30'0"E 25°0'0"E 27°30'0"E 30°0'0"E Central African Republic N N " " 0 0 ' Sudan ' 0 0 ° ° 5 5 Z o n g oBangui Mobayi Bosobolo Gbadolite Yakoma Ango Yaounde Bondo Nord Ubangi Niangara Faradje Cameroon Libenge Bas Uele Dungu Bambesa Businga G e m e n a Haut Uele Poko Rungu Watsa Sud Ubangi Aru Aketi B u tt a II s ii rr o r e Kungu Budjala v N i N " R " 0 0 ' i ' g 0 n 0 3 a 3 ° b Mahagi ° 2 U L ii s a ll a Bumba Wamba 2 Orientale Mongala Co Djugu ng o R i Makanza v Banalia B u n ii a Lake Albert Bongandanga er Irumu Bomongo MambasaIturi B a s a n k u s u Basoko Yahuma Bafwasende Equateur Isangi Djolu Yangambi K i s a n g a n i Bolomba Befale Tshopa K i s a n g a n i Beni Uganda M b a n d a k a N N " Equateur " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Lubero ° 0 Ingende B o e n d e 0 Gabon Ubundu Lake Edward Opala Bikoro Bokungu Lubutu North Kivu Congo Tshuapa Lukolela Ikela Rutshuru Kiri Punia Walikale Masisi Monkoto G o m a Yumbi II n o n g o Kigali Bolobo Lake Kivu Rwanda Lomela Kalehe S S " KabareB u k a v u " 0 0 ' ' 0 Kailo Walungu 0 3 3 ° Shabunda ° 2 2 Mai Ndombe K ii n d u Mushie Mwenga Kwamouth Maniema Pangi B a n d u n d u Bujumbura Oshwe Katako-Kombe South Kivu Uvira Dekese Kole Sankuru Burundi Kas ai R Bagata iver Kibombo Brazzaville Ilebo Fizi Kinshasa Kasongo KasanguluKinshasa Bandundu Bulungu Kasai Oriental Kabambare K e n g e Mweka Lubefu S Luozi L u s a m b o S " Tshela Madimba Kwilu Kasai -

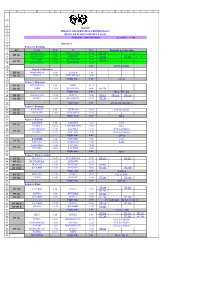

UNHAS DRC Weekly Flight Schedule

UNHAS DRC Weekly Flight Schedule Effective from 09th June 2021 AIRCRAFT MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY KINSHASA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:00 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:30 08:30 KINSHASA BRAZZAVILLE 08:45 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:30 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:30 UNO-234H 09:30 MBANDAKA GBADOLITE 10:55 10:00 MBANDAKA YAKOMA 11:40 09:30 BRAZZAVILLE MBANDAKA 11:00 10:00 MBANDAKA GBADOLITE 11:25 10:00 MBANDAKA LIBENGE 11:00 5Y-VVI 11:25 GBADOLITE BANGUI 12:10 12:10 YAKOMA MBANDAKA 13:50 11:30 MBANDAKA IMPFONDO 12:00 11:55 GBADOLITE MBANDAKA 13:20 11:30 LIBENGE BANGUI 11:50 DHC-8-Q400 13:00 BANGUI MBANDAKA 14:20 14:20 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 15:50 12:30 IMPFONDO MBANDAKA 13:00 13:50 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 15:20 12:40 BANGUI MBANDAKA 14:00 SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE 14:50 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 16:20 13:30 MBANDAKA BRAZZAVILLE 15:00 14:30 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 16:00 15:30 BRAZZAVILLE KINSHASA 15:45 AD HOC CARGO FLIGHT TSA WITH UNHCR KINSHASA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA 09:00 KINSHASA KANANGA 11:15 08:00 KINSHASA KALEMIE 11:15 09:00 KINSHASA KANANGA 11:15 UNO-207H 11:45 KANANGA GOMA 13:10 11:45 KALEMIE GOMA 12:35 11:45 KANANGA GOMA 13:10 5Y-CRZ SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE EMB-145 LR 14:10 GOMA KANANGA 15:35 13:35 GOMA KINSHASA 14:50 14:10 GOMA KANANGA 15:35 16:05 KANANGA KINSHASA 16:20 16:05 KANANGA KINSHASA 16:20 -

Radio Okapi's Contribution to the Peace Process in The

PUBLIC INFORMATION AND THE MEDIA: RADIO OKAPI’S CONTRIBUTION TO THE PEACE PROCESS IN THE DRC Jerome Ngongo Taunya1 Introduction There are many reasons to be optimistic about the progress made thus far on the way to peace in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The DRC now has one government, one parliament, one army commander. This much has already been achieved. However, we still have a long way to go before making this process a success. The northeastern Ituri district and the two Kivu provinces are still unstable; the question of the integration of the armies and police remains and is yet to be addressed; several delicate issues still face the new government; and all the transitional institutions will need some time to be consolidated. The electoral challenge, which is the final objective of the process, is still to be met, and this will require a great deal of commitment from those working in public infor- mation. Therefore, media support to the peace process must continue apace. The role of the media and the public information division of MONUC is certainly crucial. The success of the reconciliation process will depend heavily on the capacity of the Congolese media to capture the attention of the population, to provide them with fluid, useful, and balanced information. The media are needed to harness wide participation in the process by the Congolese people. The people of Congo need to be given the tools to allow them to master their destiny. They need to be accurately informed and educated, so they can better understand what is done for them and what they have to do for themselves. -

OCHA DRC Kinshasa Goma Kisangani Kisangani Bukavu Bunia

OCHA DRC Kinshasa Goma Kisangani Bukavu Bunia Mbandaka CONTEXT More than ever before since the onset of the war, the reporting period provided ample and eloquent arguments to perceive the humanitarian crisis in the DRC as a unique drama caused in the first place by unbridled violence, defiant impunity and ongoing violation of fundamental humanitarian principles. What comes first is the cold-blooded settlement of scores between two foreign troops in DRC’s third largest town, using heavy armament and ignoring humanitarian cease-fires in a total disregard for the fate of 600,000 civilians. Such exceptional circumstances led to the non less remarkable adoption of the UNSC Resolution 1304, marked by references to Chapter VII of the UN Charter, and by the presence of Ugandan and Rwandan Foreign ministers. Parallel to blatant violations of humanitarian principles, the level of daily mortality as a direct effect of the ongoing war in eastern DRC, as surveyed recently by International Rescue Committee, gives a horrific account of the silent disaster experienced by Congolese civilians in eastern provinces. Daily violence, mutual fears combined with shrinking access to most basic health services, are breeding an environment of vulnerability that led civilians of Kivu to portray themselves as the “wrecked of the earth”. In a poorly inhabited and remote province such as Maniema, an FAO mission estimated at 68% of the population the proportion of those who had to flee from home at one point since August 1998 (110,000 are still hiding in the forest). A third, most ordinary facet of DRC’s humanitarian crisis, is that witnessed by a humanitarian team in a village on the frontline in northern Katanga, where the absence of food and non food trade across the frontline (with the exception of discreet exchanges between troops) brings both displaced and host communities on the verge of starvation. -

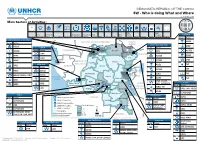

Who Is Doing What and Where As of 31 May, 2018 Main Sectors of Activities

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO 3W - Who is doing What and Where as of 31 May, 2018 Main Sectors of Activities : Multi- Water, Camp Community Empowerment Environmental Food Multi- sectoral Sanitation BAS UELE Basic Needs Management Service Data Collection Education and Self-reliance Protection Security Health Livelihood Logistic Sector protection Nutrition Protection Shelter and Hygiene Distribution Sector Partner NORD UBANGI & SUD UBANGI CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SOUTH ADES Sector Partner Bili SUDAN HAUT UELE AND ITURI ADSSE Zongo Gbadolite AIRD GABON Monga Aba Sector Partner Bight of Dungu Sector Partner Libenge ADSSE Biafra CAMEROON Nord-Ubangi Bas-Uele Aru DRC ACTED Haut-Uele CNR Sud-Ubangi UGANDA ADES Mongala ADSSE ADES Gulf of Lake CNR Ituri Albert Guinea Bunia ADES COOPI CNR REPUBLIC OF Tshopo Libreville Equateur KINSHASA THE CONGO Lake Edward ADES TSF AIRD GABON Tshuapa Sector Partner Goma Lake Victoria ADSSE TSF ADES ADSSE RWANDA Bukavu Mai-Ndombe TSF Sud-Kivu AIRD ADSSE, AIDES, CNR ADSSE BURUNDI ATLANTIC Sankuru Uvira Baraka ADES ADSSE Kinshasa Maniema TSF AIRD OCEAN Kasai Kwilu Kasai CNR, COOPI, Kongo Central Central UNITED SUD KIVU ADES AIRD Kalemie DRC, INTERSOS Tshikapa Mbuji-Mayi Lomami Sector Partner REPUBLIC OF AIRD, TSF CNR Kwango Kananga Kasai Tanganyika Lake TANZANIA AIRD, CNR, AIDES Oriental Tanganyika ADES Haut-Lomami ACTIONAID KASAI NORD KIVU Sector Partner UNHCR Regional Office ANGOLA Lake Mweru ADRA Haut-Katanga Sector Partner ACTIONAID UNHCR Sub-Office Lualaba ADRA AIRD UNHCR Country-Office ADRA, AIDES OIM UNHCR Field Office Number of Sectoral Activities Lubumbashi AIDES, CNR, 0 UNHCR Field Unit INTERSOS ACTIONAID 0 - 1 ADES Hydrography ACTIONAID, WAR 1 - 7 International boundary 7 - 13 AIRD CHILD UK, CNR, NRC ZAMBIA Provincial boundary 13 - 15 100km The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply ocial endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Rapport Final De L'accident De L'aeronef De Type Beech

BUREAU PERMANENT D’ENQUÊTES ACCIDENTS D’AVIATIONS RAPPORT FINAL D’ENQUETE Page 1 TECHNIQUE SUR L’ACCIDENT DE Date : 17/09/2014 L’AERONEF DE TYPE BEECH SUPER KINGAIR 200 IMMATRICULE 9Q-CAJ RAPPORT FINAL DE L’ACCIDENT DE L’AERONEF DE TYPE BEECH CRAFTB-200 IMMATRICULE 9Q-CAJ, DE LA COMPAGNIE AERIENNE AIR TROPIQUES SURVENU LE 27 JUIN 2014 A BUKAVU BUREAU PERMANENT D’ENQUÊTES ACCIDENTS D’AVIATIONS RAPPORT FINAL D’ENQUETE Page 2 TECHNIQUE SUR L’ACCIDENT DE Date : 17/09/2014 L’AERONEF DE TYPE BEECH SUPER KINGAIR 200 IMMATRICULE 9Q-CAJ Table des matières GLOSSAIRE ............................................................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 5 TITRE .................................................................................................................................................... 5 SYNOPSIS ............................................................................................................................................. 5 ORGANISATION DE L’ENQUETE ............................................................................................................. 6 RESUME ............................................................................................................................................... 6 RENSEIGNEMENTS DE BASE .................................................................................................................. -

MONUC MAOC Regular Flight Schedule PUB 060116

ABCDEFGHIJ 1 2 3 MONUC 4 MISSION AIR OPERATION CENTER(MAOC) 5 REGULAR FLIGHT SCHEDULE (PAX) 6 JANUARY 2006 EDITION) AVAMDT 01/06 7 8 MONDAY 9 Region 10- Kinshasa 10 RF# From ETD To ETA Remarks & Connection 11 KINSHASA 8:00 KISANGANI 10:45 RF 123 RF 101 12 KISANGANI 11:50 ENTEBBE 14:00 RF-152 RF 163 RF-151A 13 ENTEBBE 16:00 KISANGANI 16:10 RF124 RF 102 14 KISANGANI 17:10 KINSHASA 17:55 15 5:50 B-727-COMBI 16 Region 1-Mbandaka 17 RF 111 MBANDAKA 8:30 LISALA 9:50 18 RF 112 LISALA 14:30 MBANDAKA 15:50 19 Flight time: 2:40 AN-24 20 Region 2- Kisangani 21 RF 121 KISANGANI 8:15 ISIRO 10:15 22 RF 122 ISIRO 14:00 KISANGANI 16:00 RF-102 23 Flight time: 4:00 MI-8 / BE -200 24 RF 123 KISANGANI 11:30 BUNIA 13:00 RF101 RF160B RF-166 25 RF 124 BUNIA 15:00 KISANGANI 16:30 RF-102 26 Flight time 3:00 AN-24 /BE-200/ MI -8 27 Region 3- Kananga 28 RF 131 KANANGA 9:00 TSHIKAPA 10:10 PAX &CARGO 29 RF 132 TSHIKAPA 14:00 KANANGA 15:10 30 Flight Time: 2:20 MI-8 31 Region 4- Kalemie 32 KALEMIE 8:00 KAMINA 9:30 PAX RF 141 33 KAMINA 10:00 LUBUMBASHI 11:00 PAX 34 LUBUMBASHI 14:30 KAMINA 15:30 PAX & CARGO RF 142 35 KAMINA 16:00 KALEMIE 17:30 PAX & CARGO 36 Flight time: 5:00 AN-72 37 KALEMIE 8:00 NYUNZU 9:00 PAX RF 143 38 NYUNZU 10:00 KONGOLO 11:00 PAX 39 KONGOLO 12:00 NYUNZU 13:00 RF 144 40 NYUNZU 14:00 KALEMIE 15:00 41 Flight time: 4:00 MI-8 42 Region 5- Bukavu / Kindu 43 RF 151 BUKAVU 10:00 BUJUMBURA 10:30 RF-172 RF 163 44 RF-152 BUJUMBURA 11:45 BUKAVU 12:05 45 RF151A BUKAVU 12:45 ENTEBBE 15:05 RF102 46 RF 151B ENTEBBE 15:45 BUKAVU 16:05 RF-184 RF-186 47 Flight time: -

Rapport Annuel 2014

Rapport Annuel 2014 FONDS POUR LES FEMMES CONGOLAISES Site web: www.ffcrdc.org - E-mail: [email protected] Téléphone +243-822-221-195, Numéro Id.Nat :P04597L N°Impôt : A1104830N 1527 av. Colonel Mondjiba-Kinshasa/Ngaliema République Démocratique du Congo TABLE DES MATIERES ACRONYME ET ABREVIATION...................................................................................................................... 4 QUI SOMMES NOUS? ........................................................................................................................................ 6 CONTEXTE ........................................................................................................................................................... 7 I. OCTROI DES SUBVENTIONS AUX ORGANISATIONS DE FEMMES/FILLES .............................. 9 I.A. DIAGNOSTIC INSTITUTIONNEL, SUIVI ET EVALUATION DES PROJETS ................................ 10 I.B. QUELQUES EXEMPLES DE PROJETS APPUYES EN 2014. ............................................................ 11 A) LEADERSHIP FEMININ ET PARTICIPATION DES FEMMES AUX INSTANCES DE PRISE DES DECISIONS ......................................................................................................................................................................... 11 B) VIOLENCES SEXUELLES ET CELLES BASEES SUR LE GENRE .................................................................. 12 C) VIH/SIDA ET SANTE DE LA REPRODUCTION ............................................................................................... -

Conflict and Displacement in Nord Kivu and Ituri Briefing Note – 14 May 2019

DRC Conflict and displacement in Nord Kivu and Ituri Briefing note – 14 May 2019 Since 1 May, attacks and clashes between armed groups and Congolese security forces triggered the displacement of more than 12,000 people in Nord Kivu and Ituri provinces in eastern DRC. Although exact numbers and humanitarian needs of newly displaced people are unknown, they add to more than 100,000 people who were displaced in Nord Kivu in April. Food, WASH, health, protection and shelter are reported as imminent needs of displaced people, who currently rely on host communities to meet their most basic needs. Anticipated scope and scale Key priorities Humanitarian constraints Attacks by armed groups, particularly the Allied Democratic Humanitarian access can be challenging in +12,000 Forces (ADF), have increased in frequency in recent eastern DRC due to the volatile security situation, people displaced months and are likely to trigger more displacement and remoteness, and poor condition of roads. The drive humanitarian needs in Nord Kivu and Ituri province. ongoing rainy season and an increase of attacks The lack of humanitarian assistance is likely to push WASH by the armed group ADF since December likely displaced communities to prematurely return to areas of further hampers access. assistance to prevent spread of origin, despite persistent protection concerns. diseases Displacement in Ebola-affected territories could Limitations Food & livelihoods facilitate spreading of the disease. IDPs resorting to informal Detailed and reliable information on security incidents and internal displacement is scarce in conflict-affected Nord Kivu. Local media provide crossings to Uganda, without screening, increase the risk of assistance for displaced people only fragmented insight into local security incidents in the provinces Ebola spreading to neighbouring countries.