Radio Okapi's Contribution to the Peace Process in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Unhas Drc Schedule Effect

UNHAS DRC FLIGHT SCHEDULE EFFECTIVE FROM SEPTEMBER 11th 2017 All Planned Flight Times are in LOCAL TIME: Kinshasa, Mbandaka, Brazzaville, Impfondo, Enyelle, Gemena, Libenge, Gbadolite, Zongo, Bangui (UTC + 1); All Other Destinations (UTC + 2) PASSENGERS ARE TO CHECK IN 2 HOURS BEFORE SCHEDULE TIME OF DEPARTURE - PLEASE NOTE THAT THE COUNTER WILL BE CLOSED 1 HOUR BEFORE TIME OF THE DEPARTURE MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY AIRCRAFT DESTINATION DEP ARR DESTINATION DEP ARR DESTINATION DEP ARR DESTINATION DEP ARR DESTINATION DEP ARR KINSHASA MBANDAKA 7:30 9:00 SPECIAL FLIGHTS KINSHASA BRAZZAVILLE 7:30 7:45 SPECIAL FLIGHTS KINSHASA MBANDAKA 7:30 9:00 SPECIAL FLIGHTS SPECIAL FLIGHTS UNO 113H MBANDAKA LIBENGE 9:30 10:30 BRAZZAVILLE MBANDAKA 8:45 10:15 MBANDAKA GBADOLITE 9:30 10:50 DHC8 LIBENGE ZONGO 11:00 11:20 MBANDAKA IMPFONDO 10:45 11:15 GBADOLITE BANGUI 11:20 12:05 5Y-STN ZONGO BANGUI 11:50 12:00 OR IMPFONDO ENYELLE 11:45 12:10 OR BANGUI LIBENGE 13:05 13:25 OR OR BANGUI GBADOLITE 13:00 13:45 ENYELLE MBANDAKA 12:40 13:30 LIBENGE MBANDAKA 13:55 14:55 GBADOLITE MBANDAKA 14:15 15:35 MBANDAKA BRAZZAVILLE 14:00 15:30 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 15:25 16:55 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 16:05 17:35 MAINTENANCE BRAZZAVILLE KINSHASA 16:00 16:15 MAINTENANCE MAINTENANCE MAINTENANCE KINSHASA KANANGA 7:15 9:30 SPECIAL FLIGHTS KINSHASA GOMA 7:15 10:30 SPECIAL FLIGHTS KINSHASA KANANGA 7:15 9:30 SPECIAL FLIGHTS SPECIAL FLIGHTS UNO 213H KANANGA KALEMIE 10:00 11:05 GOMA KALEMIE 12:15 13:05 KANANGA GOMA 10:00 11:25 EMB-135 KALEMIE GOMA 11:45 12:35 OR KALEMIE -

IMCK Newsletter 17.3.Pages

INSTITUT MEDICAL CHRETIEN DU KASAI !1 OFINSTITUT MEDICAL!5 CHRETIEN DU KASAI B.P. 205 KANANGA B.P. 205 KANANGA INSTITUT MEDICAL CHRETIENREPUBLIQUE DEMOCRATIQUE DU DUKASAI CONGO REPUBLIQUE DEMOCRATIQUE DU CONGO Christian Medical Institute Hôpitalof – theEcole d’infirmiers Kasai – Ecole de laborantins - Serving – Service de santé communautairein Central - Service d’ophtalmologie Congo Service dentaire – Centre d’études et de recyclage Hôpital – Ecole d’infirmiers – Ecole de laborantins – Service de santé communautaire - Service d’ophtalmologie E-mail : [email protected] Service dentaire – Centre d’études et de recyclage B. P. 205 Kananga, Republic Democratic du Congo ; Email: [email protected] E-mail : [email protected] 2. Find a way to channel a greater percentage of donations back into that unpopular category 2. Find a way to channel a greater percentage of donations back into that unpopular category of “undesignated” gifts so that we can have the flexibility to apply them where A Periodic Newsletter operational needs are Issuethe most desperate. No. 41 But ifJanuary you cannot (and - thatMarch is understandable, 2017 of “undesignated” gifts so that we can have the flexibility to apply them whereA considering all the news stories one sees about mismanaged funds), then consider operational needs are the most desperate. But if you cannot (and that is understandable, designating gifts carefully to those things that are at the core of IMCK’s operational considering all the news stories one sees about mismanaged funds), then consider The current conflict in the Kasai has needs.I askedFor example the new: Specify IMCK money Administrator, for medicines and Kastin medical Katawa, supplies; Specifyto describe money designating gifts carefully to those things that are at the core of IMCK’s operational added new suffering and danger. -

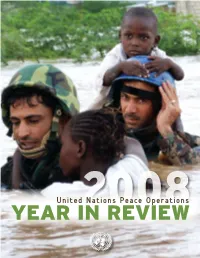

Year in Review 2008

United Nations Peace Operations YEAR IN2008 REVIEW asdf TABLE OF CONTENTS 12 ] UNMIS helps keep North-South Sudan peace on track 13 ] MINURCAT trains police in Chad, prepares to expand 15 ] After gaining ground in Liberia, UN blue helmets start to downsize 16 ] Progress in Côte d’Ivoire 18 ] UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea is withdrawn 19 ] UNMIN assists Nepal in transition to peace and democracy 20 ] Amid increasing insecurity, humanitarian and political work continues in Somalia 21 ] After nearly a decade in Kosovo, UNMIK reconfigures 23 ] Afghanistan – Room for hope despite challenges 27 ] New SRSG pursues robust UN mandate in electoral assistance, reconstruction and political dialogue in Iraq 29 ] UNIFIL provides a window of opportunity for peace in southern Lebanon 30 ] A watershed year for Timor-Leste 33 ] UN continues political and peacekeeping efforts in the Middle East 35 ] Renewed hope for a solution in Cyprus 37 ] UNOMIG carries out mandate in complex environment 38 ] DFS: Supporting peace operations Children of Tongo, Massi, North Kivu, DRC. 28 March 2008. UN Photo by Marie Frechon. Children of Tongo, 40 ] Demand grows for UN Police 41 ] National staff make huge contributions to UN peace 1 ] 2008: United Nations peacekeeping operations observes 60 years of operations 44 ] Ahtisaari brings pride to UN peace efforts with 2008 Nobel Prize 6 ] As peace in Congo remains elusive, 45 ] Security Council addresses sexual violence as Security Council strengthens threat to international peace and security MONUC’s hand [ Peace operations facts and figures ] 9 ] Challenges confront new peace- 47 ] Peacekeeping contributors keeping mission in Darfur 48 ] United Nations peacekeeping operations 25 ] Peacekeepers lead response to 50 ] United Nations political and peacebuilding missions disasters in Haiti 52 ] Top 10 troop contributors Cover photo: Jordanian peacekeepers rescue children 52 ] Surge in uniformed UN peacekeeping personnel from a flooded orphanage north of Port-au-Prince from1991-2008 after the passing of Hurricane Ike. -

Ituri:Stakes, Actors, Dynamics

ITURI STAKES, ACTORS, DYNAMICS FEWER/AIP/APFO/CSVR would like to stress that this report is based on the situation observed and information collected between March and August 2003, mainly in Ituri and Kinshasa. The 'current' situation therefore refers to the circumstances that prevailed as of August 2003, when the mission last visited the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the Swedish International Development Agency. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Swedish Government and its agencies. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the Department for Development Policy, Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Finnish Government and its agencies. Copyright 2003 © Africa Initiative Program (AIP) Africa Peace Forum (APFO) Centre for Study of Violence and Reconciliation (CSVR) Forum on Early Warning and Early Response (FEWER) The views expressed by participants in the workshop are not necessarily those held by the workshop organisers and can in no way be take to reflect the views of AIP, APFO, CSVR and FEWER as organisations. 2 List of Acronyms............................................................................................................................... 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...................................................................................................................................... -

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS for the DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20 BAS-UELE HAUT-UELE ITURI S O U T H S U D A N COUNTRYWIDE NORTH KIVU OCHA IMA World Health Samaritan’s Purse AIRD Internews CARE C.A.R. Samaritan’s Purse Samaritan’s Purse IMA World Health IOM UNHAS CAMEROON DCA ACTED WFP INSO Medair FHI 360 UNICEF Samaritan’s Purse Mercy Corps IMA World Health NRC NORD-UBANGI IMC UNICEF Gbadolite Oxfam ACTED INSO NORD-UBANGI Samaritan’s WFP WFP Gemena BAS-UELE Internews HAUT-UELE Purse ICRC Buta SCF IOM SUD-UBANGI SUD-UBANGI UNHAS MONGALA Isiro Tearfund IRC WFP Lisala ACF Medair UNHCR MONGALA ITURI U Bunia Mercy Corps Mercy Corps IMA World Health G A EQUATEUR Samaritan’s NRC EQUATEUR Kisangani N Purse WFP D WFPaa Oxfam Boende A REPUBLIC OF Mbandaka TSHOPO Samaritan’s ATLANTIC NORTH GABON THE CONGO TSHUAPA Purse TSHOPO KIVU Lake OCEAN Tearfund IMA World Health Goma Victoria Inongo WHH Samaritan’s Purse RWANDA Mercy Corps BURUNDI Samaritan’s Purse MAI-NDOMBE Kindu Bukavu Samaritan’s Purse PROGRAM KEY KINSHASA SOUTH MANIEMA SANKURU MANIEMA KIVU WFP USAID/BHA Non-Food Assistance* WFP ACTED USAID/BHA Food Assistance** SA ! A IMA World Health TA N Z A N I A Kinshasa SH State/PRM KIN KASAÏ Lusambo KWILU Oxfam Kenge TANGANYIKA Agriculture and Food Security KONGO CENTRAL Kananga ACTED CRS Cash Transfers For Food Matadi LOMAMI Kalemie KASAÏ- Kabinda WFP Concern Economic Recovery and Market Tshikapa ORIENTAL Systems KWANGO Mbuji T IMA World Health KWANGO Mayi TANGANYIKA a KASAÏ- n Food Vouchers g WFP a n IMC CENTRAL y i k -

UNJHRO) MONUSCO – OHCHR March 2021 REPORTED HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS in DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO (DRC)

Protection of civilians: Human rights violations documented in provinces affected by conflict United Nations Joint Human Rights Office in the DRC (UNJHRO) MONUSCO – OHCHR March 2021 REPORTED HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO (DRC) Figure 1. Percentage of violations per territory Figure 2. Number of violations per province in DRC SOUTH CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SUDAN North Kivu Tanganyika Bas-Uele Haut-Uele Masisi 79% 21 Kalemie 36% 65 North-Ubangi Beni 64 36 Manono0 100 2 UGANDA CAMEROON South-Ubangi Rutshuru 69 31 Moba0 100 Ituri Mongala Lubero 29 71 77 Nyiragongo 86 14 Maniema Tshopo Walikale 90 10 Kabambare 63% 395 CONGO Equateur North Butembo0 100 Kasongo0 100 Kivu Kibombo0 100 GABON Tshuapa 359 South Kivu RWANDA Kasai Shabunda 82% 18 Mai-Ndombe Kamonia (Kas.)0 100% Kinshasa Uvira 33 67 5 BURUNDI Llebo (Kas.)0 100 Sankuru 15 63 Fizi 33 67 Kasai South Tshikapa (Kas.)0 100 Maniema Kivu Kabare 100 0 Luebo (Kas.)0 100 Kwilu 23 TANZANIA Walungu 29 71 Kananga (Kas. C)0 100 Lomami Bukavu0 100 22 4 Demba (Kas. C)0 100 Kongo 46 Mwenga 67 33 Central Luiza (Kas. C)0 100 Kwango Tanganyika Kalehe0 100 Kasai Dimbelenge (Kas. C)0 100 Central Haut-Lomami Ituri Miabi (Kas. O)0 100 Kasai 0 100 ANGOLA Oriental Irumu 88% 12 Mbuji-Mayi (Kas. O) Haut- Djugu 64 36 Lualaba Bas-Uele Katanga Mambasa 30 70 Buta0 100% Mahagi 100 0 % by armed groups % by State agents The boundaries and names shown and designations ZAMBIA used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

DR-CONGO December 2013

COUNTRY REPORT: DR-CONGO December 2013 Introduction: other provinces are also grappling with consistently high levels of violence. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DR-Congo) is the sec- ond most violent country in the ACLED dataset when Likewise, in terms of conflict actors, recent international measured by the number of conflict events; and the third commentary has focussed very heavily on the M23 rebel most fatal over the course of the dataset’s coverage (1997 group and their interactions with Congolese military - September 2013). forces and UN peacekeepers. However, while ACLED data illustrates that M23 has constituted the most violent non- Since 2011, violence levels have increased significantly in state actor in the country since its emergence in April this beleaguered country, primarily due to a sharp rise in 2012, other groups including Mayi Mayi militias, FDLR conflict in the Kivu regions (see Figure 1). Conflict levels rebels and unidentified armed groups also represent sig- during 2013 to date have reduced, following an unprece- nificant threats to security and stability. dented peak of activity in late 2012 but this year’s event levels remain significantly above average for the DR- In order to explore key dynamics of violence across time Congo. and space in the DR-Congo, this report examines in turn M23 in North and South Kivu, the Lord’s Resistance Army Across the coverage period, this violence has displayed a (LRA) in northern DR-Congo and the evolving dynamics of very distinct spatial pattern; over half of all conflict events Mayi Mayi violence across the country. The report then occurred in the eastern Kivu provinces, while a further examines MONUSCO’s efforts to maintain a fragile peace quarter took place in Orientale and less than 10% in Ka- in the country, and highlights the dynamics of the on- tanga (see Figure 2). -

Justice - Plus

JUSTICE - PLUS PANEL OF RESEARCH ON THE PROLIFERATION AND ILLICIT TRAFFIC OF SMALL ARMS AND LIGHT WEAPONS IN THE FRONTIER AREAS BETWEEN SUDAN, UGANDA AND THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO PROLIFERATION AND ILLICIT TRAFFIC OF SMALL ARMS AND LIGHT WEAPONS IN THE NORTH EAST OF THE DRC Summary Report by Flory KAYEMBE SHAMBA Désiré NKOY ELELA Missak KASONGO MUZEU Kinshasa, January 2003 JUSTICE-PLUS • BUNIA • KINSHASA Siège social Bureau de liaison 39bis, Av. KASAVUBU,Q. Lumumba 3, Av. KITONA, Q. Righini, C/Lemba B.P 630-BUNIA B.P. 2063 Kinshasa 1 Tél. : (+) 871762568941 tél. : (+)243 98171 100 Fax : (+)871762568943 Fax : (+) 243 8801826 E-mail : [email protected] E-mail : [email protected] research on the proliferation and illicit traffic of small arms and light weapons in the north east of the drc – flodémis 1 _______________________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS INITIALS……..…………………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………….……………………………………………………………… 3 INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………………………………. 4 I. CONCEPTUAL AND METHODOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK …………………………..………….. 6 TERMES DE REFERENCE……………………………………………………………………… 6 METHODOLOGY AND UNFOLDING OF THE RESEARCH……………………………. 9 II. OUTLINE OF THE SITUATION IN THE NORTH EAST OF THE DRC ………………….. 10 MAPPING OF CONFLITS IN ITURI AND UPPER UELE (Alliances and counter-alliances)…………………………………………………………..…….. 12 III. PRESENTATION OF DATE BY INVESTIGATION CENTRE………………………………… 13 IV. SUMMARY OF RESEARCH FINDINGS ……………………..……………………………….… 14 4.1. GENERAL PERCEPTION OF THE CONFLITS ……………………………………... 14 4.2. SMALL ARMS AND LIGHT WEAPONS : CIRCUITS OF ACQUISITION, COST, SOURCES OF SUPPLY, COMMERCIAL FLOW, IMPORTANCE …………………………………………………………………………….. 17 4.3. CONTROL OF THE CIRCULATION OF SMALL ARMS & LIGHT WEAPONS AND PROSPECTS FOR PEACE IN AFRICA’S GREAT LAKES REGION …………… 20 4.4. VERIFICATION OF RESEARCH HYPOTHESES ……………………………..…… 23 V. STRATEGIES OF FIGHT AND RECOMMENDATIONS ………………………………………… 26 5.1. -

Democratic Republic of Congo Democratic Republic of Congo Gis Unit, Monuc Africa

Map No.SP. 103 ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO GIS UNIT, MONUC AFRICA 12°30'0"E 15°0'0"E 17°30'0"E 20°0'0"E 22°30'0"E 25°0'0"E 27°30'0"E 30°0'0"E Central African Republic N N " " 0 0 ' Sudan ' 0 0 ° ° 5 5 Z o n g oBangui Mobayi Bosobolo Gbadolite Yakoma Ango Yaounde Bondo Nord Ubangi Niangara Faradje Cameroon Libenge Bas Uele Dungu Bambesa Businga G e m e n a Haut Uele Poko Rungu Watsa Sud Ubangi Aru Aketi B u tt a II s ii rr o r e Kungu Budjala v N i N " R " 0 0 ' i ' g 0 n 0 3 a 3 ° b Mahagi ° 2 U L ii s a ll a Bumba Wamba 2 Orientale Mongala Co Djugu ng o R i Makanza v Banalia B u n ii a Lake Albert Bongandanga er Irumu Bomongo MambasaIturi B a s a n k u s u Basoko Yahuma Bafwasende Equateur Isangi Djolu Yangambi K i s a n g a n i Bolomba Befale Tshopa K i s a n g a n i Beni Uganda M b a n d a k a N N " Equateur " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Lubero ° 0 Ingende B o e n d e 0 Gabon Ubundu Lake Edward Opala Bikoro Bokungu Lubutu North Kivu Congo Tshuapa Lukolela Ikela Rutshuru Kiri Punia Walikale Masisi Monkoto G o m a Yumbi II n o n g o Kigali Bolobo Lake Kivu Rwanda Lomela Kalehe S S " KabareB u k a v u " 0 0 ' ' 0 Kailo Walungu 0 3 3 ° Shabunda ° 2 2 Mai Ndombe K ii n d u Mushie Mwenga Kwamouth Maniema Pangi B a n d u n d u Bujumbura Oshwe Katako-Kombe South Kivu Uvira Dekese Kole Sankuru Burundi Kas ai R Bagata iver Kibombo Brazzaville Ilebo Fizi Kinshasa Kasongo KasanguluKinshasa Bandundu Bulungu Kasai Oriental Kabambare K e n g e Mweka Lubefu S Luozi L u s a m b o S " Tshela Madimba Kwilu Kasai -

Dismissed! Victims of 2015-2018 Brutal Crackdowns in the Democratic Republic of Congo Denied Justice

DISMISSED! VICTIMS OF 2015-2018 BRUTAL CRACKDOWNS IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DENIED JUSTICE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: “Dismissed!”. A drawing by Congolese artist © Justin Kasereka (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 62/2185/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 2. METHODOLOGY 9 3. BACKGROUND: POLITICAL CRISIS 10 3.1 ATTEMPTS TO AMEND THE CONSTITUTION 10 3.2 THE « GLISSEMENT »: THE LONG-DRAWN-OUT ELECTORAL PROCESS 11 3.3 ELECTIONS AT LAST 14 3.3.1 TIMELINE 15 4. VOICES OF DISSENT MUZZLED 19 4.1 ARBITRARY ARRESTS, DETENTIONS AND SYSTEMATIC BANS ON ASSEMBLIES 19 4.1.1 HARASSMENT AND ARBITRARY ARRESTS OF PRO-DEMOCRACY ACTIVISTS AND OPPONENTS 20 4.1.2 SYSTEMATIC AND UNLAWFUL BANS ON ASSEMBLY 21 4.2 RESTRICTIONS OF THE RIGHT TO SEEK AND RECEIVE INFORMATION 23 5. -

FLASH INFO Liste Non Exhaustive Des Opérateurs Aériens Commerciaux De Fret De RDC

FLASH INFO Liste non exhaustive des opérateurs aériens commerciaux de fret de RDC Dans le but de faciliter les démarches des organisations humanitaires, le Cluster Logistique propose ce document informatif concernant les contacts, capacités et tarifs de certains opérateurs aériens commerciaux. Cependant nous tenons à signaler que cette liste vous est donnée à titre purement indicatif et que nous ne garantissons aucuns services. The Logistics Cluster is supported by the “Global Logistic Cluster Cell” Article written on 26 June 2009 Nom du adresse Personne à Adresse téléphone Type capacité transporteur contacter mail d’avions BANNAIR Mr Felly Kabeya.felly 0999921837 1 avion 25 tonnes Kabeha @yahoo.fr 0851306451 Boeing 727 SUPER C.A.A. Route des Tel commercia 0999939807 1 avion 25 tonnes Compagnie poids lourds Boeing super Africaine n1 727 d’Aviation Quartier Dépôt 0851462195 2 Antonov 6 tonnes Site web: Kingabwa/ 26 www.caacongo.co Commune de Comptoir 0815093560- m Limete 0851462194 Mr Daudet Daudetmufu 0995903851 mayi@yahoo. fr Avenue Dany filairaviat@ic 0999946002 Antonov 24 Tabora 1686- Philemotte .cd FILAIR Barumbu Mimie filairaviat@ic 0999946003 Let410UVP- Kinshasa Mulowayi .cd E RDC Opérations filairaviat@ic 0819946029 .cd GOMAIR Siège social 0810193962 2 x boeing 2 x 20 tonnes avenue du 0813127105 727-100 port n 9 /12 0810842395 Kinshasa 0898629413 1 boeing 14 tonnes Gombe 0815125417 737-219 avec trois Semi cargo palettes et 57 passagers en éco. 1 boeing 291 full 737- passager de 127 sièges éco. MALU Aéroport de Marion Jean marionjeanjacques -

UNHAS DRC Weekly Flight Schedule

UNHAS DRC Weekly Flight Schedule Effective from 09th June 2021 AIRCRAFT MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY KINSHASA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:00 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:30 08:30 KINSHASA BRAZZAVILLE 08:45 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:30 08:00 KINSHASA MBANDAKA 09:30 UNO-234H 09:30 MBANDAKA GBADOLITE 10:55 10:00 MBANDAKA YAKOMA 11:40 09:30 BRAZZAVILLE MBANDAKA 11:00 10:00 MBANDAKA GBADOLITE 11:25 10:00 MBANDAKA LIBENGE 11:00 5Y-VVI 11:25 GBADOLITE BANGUI 12:10 12:10 YAKOMA MBANDAKA 13:50 11:30 MBANDAKA IMPFONDO 12:00 11:55 GBADOLITE MBANDAKA 13:20 11:30 LIBENGE BANGUI 11:50 DHC-8-Q400 13:00 BANGUI MBANDAKA 14:20 14:20 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 15:50 12:30 IMPFONDO MBANDAKA 13:00 13:50 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 15:20 12:40 BANGUI MBANDAKA 14:00 SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE 14:50 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 16:20 13:30 MBANDAKA BRAZZAVILLE 15:00 14:30 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 16:00 15:30 BRAZZAVILLE KINSHASA 15:45 AD HOC CARGO FLIGHT TSA WITH UNHCR KINSHASA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA ETD From To ETA 09:00 KINSHASA KANANGA 11:15 08:00 KINSHASA KALEMIE 11:15 09:00 KINSHASA KANANGA 11:15 UNO-207H 11:45 KANANGA GOMA 13:10 11:45 KALEMIE GOMA 12:35 11:45 KANANGA GOMA 13:10 5Y-CRZ SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE SPECIAL FLIGHTS OR MAINTENANCE EMB-145 LR 14:10 GOMA KANANGA 15:35 13:35 GOMA KINSHASA 14:50 14:10 GOMA KANANGA 15:35 16:05 KANANGA KINSHASA 16:20 16:05 KANANGA KINSHASA 16:20