DR-CONGO December 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Year in Review 2008

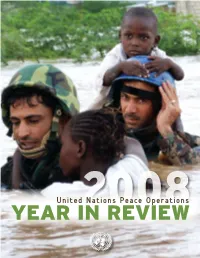

United Nations Peace Operations YEAR IN2008 REVIEW asdf TABLE OF CONTENTS 12 ] UNMIS helps keep North-South Sudan peace on track 13 ] MINURCAT trains police in Chad, prepares to expand 15 ] After gaining ground in Liberia, UN blue helmets start to downsize 16 ] Progress in Côte d’Ivoire 18 ] UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea is withdrawn 19 ] UNMIN assists Nepal in transition to peace and democracy 20 ] Amid increasing insecurity, humanitarian and political work continues in Somalia 21 ] After nearly a decade in Kosovo, UNMIK reconfigures 23 ] Afghanistan – Room for hope despite challenges 27 ] New SRSG pursues robust UN mandate in electoral assistance, reconstruction and political dialogue in Iraq 29 ] UNIFIL provides a window of opportunity for peace in southern Lebanon 30 ] A watershed year for Timor-Leste 33 ] UN continues political and peacekeeping efforts in the Middle East 35 ] Renewed hope for a solution in Cyprus 37 ] UNOMIG carries out mandate in complex environment 38 ] DFS: Supporting peace operations Children of Tongo, Massi, North Kivu, DRC. 28 March 2008. UN Photo by Marie Frechon. Children of Tongo, 40 ] Demand grows for UN Police 41 ] National staff make huge contributions to UN peace 1 ] 2008: United Nations peacekeeping operations observes 60 years of operations 44 ] Ahtisaari brings pride to UN peace efforts with 2008 Nobel Prize 6 ] As peace in Congo remains elusive, 45 ] Security Council addresses sexual violence as Security Council strengthens threat to international peace and security MONUC’s hand [ Peace operations facts and figures ] 9 ] Challenges confront new peace- 47 ] Peacekeeping contributors keeping mission in Darfur 48 ] United Nations peacekeeping operations 25 ] Peacekeepers lead response to 50 ] United Nations political and peacebuilding missions disasters in Haiti 52 ] Top 10 troop contributors Cover photo: Jordanian peacekeepers rescue children 52 ] Surge in uniformed UN peacekeeping personnel from a flooded orphanage north of Port-au-Prince from1991-2008 after the passing of Hurricane Ike. -

UN Security Council, Children and Armed Conflict in the DRC, Report of the Secretary General, October

United Nations S/2020/1030 Security Council Distr.: General 19 October 2020 Original: English Children and armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Report of the Secretary-General Summary The present report, submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 1612 (2005) and subsequent resolutions, is the seventh report of the Secretary-General on children and armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It covers the period from 1 January 2018 to 31 March 2020 and the information provided focuses on the six grave violations committed against children, the perpetrators thereof and the context in which the violations took place. The report sets out the trends and patterns of grave violations against children by all parties to the conflict and provides details on progress made in addressing grave violations against children, including through action plan implementation. The report concludes with a series of recommendations to end and prevent grave violations against children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and improve the protection of children. 20-13818 (E) 171120 *2013818* S/2020/1030 I. Introduction 1. The present report, submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 1612 (2005) and subsequent resolutions, is the seventh report of the Secretary-General on children and armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and covers the period from 1 January 2018 to 31 March 2020. It contains information on the trends and patterns of grave violations against children since the previous report (S/2018/502) and an outline of the progress and challenges since the adoption by the Working Group on Children and Armed Conflict of its conclusions on children and armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in July 2018 (S/AC.51/2018/2). -

Policy Briefing

Policy Briefing Africa Briefing N°91 Kinshasa/Nairobi/Brussels, 4 October 2012. Translation from French Eastern Congo: Why Stabilisation Failed government improves political dialogue and governance in I. OVERVIEW both the administration and in the army in the east, as rec- ommended by Crisis Group on several previous occasions. Since Bosco Ntaganda’s mutiny in April 2012 and the sub- sequent creation of the 23 March rebel movement (M23), In the short term, this crisis can be dealt with through the violence has returned to the Kivus. However today’s crisis following initiatives: bears the same hallmarks as yesterday’s, a consequence of the failure to implement the 2008 framework for resolu- the negotiation and monitoring of a ceasefire between tion of the conflict. Rather than effectively implementing the Congolese authorities and the M23 by the UN; the 23 March 2009 peace agreement signed by the gov- the reactivation of an effective and permanent joint ver- ernment and the CNDP (National Council for the Defence ification mechanism for the DRC and Rwandan border, of the People), the Congolese authorities have instead only as envisaged by the ICGLR, which should be provided feigned the integration of the CNDP into political institu- with the necessary technical and human resources; tions, and likewise the group appears to have only pretend- ed to integrate into the Congolese army. Furthermore in the addition of the individuals and entities that support- the absence of the agreed army reform, military pressure ed the M23 and other armed groups to the UN sanctions on armed groups had only a temporary effect and, more- list and the consideration of an embargo on weapons over, post-conflict reconstruction has not been accompa- sales to Rwanda; nied by essential governance reforms and political dia- the joint evaluation of the 23 March 2009 agreement logue. -

Dismissed! Victims of 2015-2018 Brutal Crackdowns in the Democratic Republic of Congo Denied Justice

DISMISSED! VICTIMS OF 2015-2018 BRUTAL CRACKDOWNS IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DENIED JUSTICE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: “Dismissed!”. A drawing by Congolese artist © Justin Kasereka (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 62/2185/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 2. METHODOLOGY 9 3. BACKGROUND: POLITICAL CRISIS 10 3.1 ATTEMPTS TO AMEND THE CONSTITUTION 10 3.2 THE « GLISSEMENT »: THE LONG-DRAWN-OUT ELECTORAL PROCESS 11 3.3 ELECTIONS AT LAST 14 3.3.1 TIMELINE 15 4. VOICES OF DISSENT MUZZLED 19 4.1 ARBITRARY ARRESTS, DETENTIONS AND SYSTEMATIC BANS ON ASSEMBLIES 19 4.1.1 HARASSMENT AND ARBITRARY ARRESTS OF PRO-DEMOCRACY ACTIVISTS AND OPPONENTS 20 4.1.2 SYSTEMATIC AND UNLAWFUL BANS ON ASSEMBLY 21 4.2 RESTRICTIONS OF THE RIGHT TO SEEK AND RECEIVE INFORMATION 23 5. -

Le Président Du Conseil De Sécurité Présente

Le Président du Conseil de sécurité présente ses compliments aux membres du Conseil et a l'honneur de transmettre, pour information, le texte d'une lettre datée du 2 juin 2020, adressée au Président du Conseil de sécurité, par le Groupe d’experts sur la République démocratique du Congo reconduit suivant la résolution 2478 (2019) du Conseil de sécurité, ainsi que les pièces qui y sont jointes. Cette lettre et les pièces qui y sont jointes seront publiées comme document du Conseil de sécurité sous la cote S/2020/482. Le 2 juin 2020 The President of the Security Council presents his compliments to the members of the Council and has the honour to transmit herewith, for their information, a copy of a letter dated 2 June 2020 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo extended pursuant to Security Council resolution 2478 (2019) addressed to the President of the Security Council, and its enclosures. This letter and its enclosures will be issued as a document of the Security Council under the symbol S/2020/482. 2 June 2020 UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES POSTAL ADDRESS-ADRESSE POSTALE: UNITED NATIONS, N.Y. 10017 CABLE ADDRESS -ADRESSE TELEGRAPHIQUE: UNATIONS NEWYORK REFERENCE: S/AC.43/2020/GE/OC.171 2 juin 2020 Monsieur Président, Les membres du Groupe d’experts sur la République démocratique du Congo, dont le mandat a été prorogé par le Conseil de sécurité dans sa résolution 2478 (2019), ont l’honneur de vous faire parvenir leur rapport final, conformément au paragraphe 4 de ladite résolution. -

Covert Networks in Conflict Zones

This is a repository copy of Brokering between (not so) overt and (not so) covert networks in conflict zones. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/156582/ Version: Published Version Article: Stys, P., Verweijen, J. orcid.org/0000-0002-4204-1172, Muzuri, P. et al. (3 more authors) (2020) Brokering between (not so) overt and (not so) covert networks in conflict zones. Global Crime, 21 (1). pp. 74-110. ISSN 1744-0572 https://doi.org/10.1080/17440572.2019.1596806 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. This licence allows you to distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon the work, even commercially, as long as you credit the authors for the original work. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Global Crime ISSN: 1744-0572 (Print) 1744-0580 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fglc20 Brokering between (not so) overt and (not so) covert networks in conflict zones Patrycja Stys, Judith Verweijen, Papy Muzuri, Samuel Muhindo, Christoph Vogel & Johan H. Koskinen To cite this article: Patrycja Stys, Judith Verweijen, Papy Muzuri, Samuel Muhindo, Christoph Vogel & Johan H. Koskinen (2020) Brokering between (not so) overt and (not so) covert networks in conflict zones, Global Crime, 21:1, 74-110, DOI: 10.1080/17440572.2019.1596806 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/17440572.2019.1596806 © 2019 The Author(s). -

Mapping Conflict Motives: M23

Mapping Conflict Motives: M23 1 Front Cover image: M23 combatants marching into Goma wearing RDF uniforms Antwerp, November 2012 2 Table of Contents Introduction 4 1. Background 5 2. The rebels with grievances hypothesis: unconvincing 9 3. The ethnic agenda: division within ranks 11 4. Control over minerals: Not a priority 14 5. Power motives: geopolitics and Rwandan involvement 16 Conclusion 18 3 Introduction Since 2004, IPIS has published various reports on the conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Between 2007 and 2010 IPIS focussed predominantly on the motives of the most significant remaining armed groups in the DRC in the aftermath of the Congo wars of 1996 and 1998.1 Since 2010 many of these groups have demobilised and several have integrated into the Congolese army (FARDC) and the security situation in the DRC has been slowly stabilising. However, following the November 2011 elections, a chain of events led to the creation of a ‘new’ armed group that called itself “M23”. At first, after being cornered by the FARDC near the Rwandan border, it seemed that the movement would be short-lived. However, over the following two months M23 made a remarkable recovery, took Rutshuru and Goma, and started to show national ambitions. In light of these developments and the renewed risk of large-scale armed conflict in the DRC, the European Network for Central Africa (EURAC) assessed that an accurate understanding of M23’s motives among stakeholders will be crucial for dealing with the current escalation. IPIS volunteered to provide such analysis as a brief update to its ‘mapping conflict motives’ report series. -

NO19-Digital Media in Central Africa.Indd

REFERENCE SERIES NO. 19 MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: NEWS AND NEW MEDIA IN CENTRAL AFRICA. CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES By Marie-Soleil Frère December 2012 News and New Media in Central Africa. Challenges and Opportunities WRITTEN BY Marie-Soleil Frère1 Th e Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is the largest country in sub-Saharan Africa. Rwanda and Burundi are among the continent’s smallest states. More than just neighbors, these three countries are locked together by overlapping histories and by extreme political and economic challenges. Th ey all score very low on the United Nations’ human development index, with DRC and Burundi among the half-dozen poorest and most corrupt countries in the world. Th ey are all recovering uncertainly from confl icts that involved violence on an immense scale, devastating communities and destroying infrastructure. Th eir populations are overwhelmingly rural and young. In terms of media, radio is by far the most popular source of news. Levels of state capture are high, and media quality is generally poor. Professional journalists face daunting obstacles. Th e threadbare markets can hardly sustain independent outlets. Amid continuing communal and political tensions, the legacy of “hate media” is insidious, and upholding journalism ethics is not easy when salaries are low. Ownership is non-transparent. Telecoms overheads are exorbitantly high. In these conditions, new and digital media—which fl ourish on consumers’ disposable income, strategic investment, and vibrant markets—have made a very slow start. Crucially, connectivity remains low. But change is afoot, led by the growth of mobile internet access. 1. Marie-Soleil Frère is Senior Research Associate at the National Fund for Scientifi c Research (Belgium) and Director of the Research Center in Information and Communication (ReSIC) at the University of Brussels. -

Radio Okapi's Contribution to the Peace Process in The

PUBLIC INFORMATION AND THE MEDIA: RADIO OKAPI’S CONTRIBUTION TO THE PEACE PROCESS IN THE DRC Jerome Ngongo Taunya1 Introduction There are many reasons to be optimistic about the progress made thus far on the way to peace in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The DRC now has one government, one parliament, one army commander. This much has already been achieved. However, we still have a long way to go before making this process a success. The northeastern Ituri district and the two Kivu provinces are still unstable; the question of the integration of the armies and police remains and is yet to be addressed; several delicate issues still face the new government; and all the transitional institutions will need some time to be consolidated. The electoral challenge, which is the final objective of the process, is still to be met, and this will require a great deal of commitment from those working in public infor- mation. Therefore, media support to the peace process must continue apace. The role of the media and the public information division of MONUC is certainly crucial. The success of the reconciliation process will depend heavily on the capacity of the Congolese media to capture the attention of the population, to provide them with fluid, useful, and balanced information. The media are needed to harness wide participation in the process by the Congolese people. The people of Congo need to be given the tools to allow them to master their destiny. They need to be accurately informed and educated, so they can better understand what is done for them and what they have to do for themselves. -

The Evolution of an Armed Movement in Eastern Congo Rift Valley Institute | Usalama Project

RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE | USALAMA PROJECT UNDERSTANDING CONGOLESE ARMED GROUPS FROM CNDP TO M23 THE EVOLUTION OF AN ARMED MOVEMENT IN EASTERN CONGO rift valley institute | usalama project From CNDP to M23 The evolution of an armed movement in eastern Congo jason stearns Published in 2012 by the Rift Valley Institute 1 St Luke’s Mews, London W11 1Df, United Kingdom. PO Box 30710 GPO, 0100 Nairobi, Kenya. tHe usalama project The Rift Valley Institute’s Usalama Project documents armed groups in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The project is supported by Humanity United and Open Square and undertaken in collaboration with the Catholic University of Bukavu. tHe rift VALLEY institute (RVI) The Rift Valley Institute (www.riftvalley.net) works in Eastern and Central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. tHe AUTHor Jason Stearns, author of Dancing in the Glory of Monsters: The Collapse of the Congo and the Great War of Africa, was formerly the Coordinator of the UN Group of Experts on the DRC. He is Director of the RVI Usalama Project. RVI executive Director: John Ryle RVI programme Director: Christopher Kidner RVI usalama project Director: Jason Stearns RVI usalama Deputy project Director: Willy Mikenye RVI great lakes project officer: Michel Thill RVI report eDitor: Fergus Nicoll report Design: Lindsay Nash maps: Jillian Luff printing: Intype Libra Ltd., 3 /4 Elm Grove Industrial Estate, London sW19 4He isBn 978-1-907431-05-0 cover: M23 soldiers on patrol near Mabenga, North Kivu (2012). Photograph by Phil Moore. rigHts: Copyright © The Rift Valley Institute 2012 Cover image © Phil Moore 2012 Text and maps published under Creative Commons license Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by/nc-nd/3.0. -

He Who Touches the Weapon Becomes Other: a Study of Participation in Armed Groups in South Kivu, Democratic Republic of The

The London School of Economics and Political Science He who touches the weapon becomes other: A Study of Participation in Armed groups In South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo Gauthier Marchais A thesis submitted to the Department of International Development of the London School of Economics and Political Science for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. London, January 2016 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgment is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 107 254 words. Gauthier Marchais London, January 2016 2 Table of Contents ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................. 7 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ........................................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 17 1.1. The persisting puzzle of participation in armed -

FY 2003 USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE to the DRC Agency Implementing Sector Regions Amount Partner FY 2003 USAID

FY 2003 USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO THE DRC Agency Implementing Sector Regions Amount Partner FY 2003 USAID ............................................................................................................................................... $35,042,261 USAID/ofda1 ..................................................................................................................................... $10,442,261 Action Against Food security Northern Katanga $700,000 Hunger/USA Province AirServ Air transport Country-wide $2,465,567 International German Agro Food security Ituri District $862,872 Action (GAA) IRC Health, and water and sanitation South Kivu Province $600,000 IRC Water and sanitation Mwenga, South Kivu $1,500,000 Province IRC Health Kalemie, Northern $500,000 Katanga Province MERLIN Health Ituri District $1,000,000 Premiere Urgence Food security Ituri District $600,000 SCF/UK Volcano monitoring and mitigation Goma, North Kivu $341,176 Province SCF/UK Child reunification Ituri District $39,386 Solidarites Food security Ituri District $71,000 UN FAO Food security Country-wide $700,000 UN OCHA Seismic monitoring and mitigation Country-wide $180,000 WFP Air transport of emergency food Northern Katanga $500,000 Province Administrative Kinshasa and $382,260 Costs Washington, D.C. USAID/FFP........................................................................................................................................ $20,000,000 WFP 21,770 MT in P.L. 480 Title II Emergency Country-wide $20,000,000 Food Assistance