Mapping Conflict Motives: M23

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catastrophes Naturelles Sud-Kivu

Deux mini-stations d’épuration d’eau installées sur les rivières Mulongwe et Kamvivira et près de 50 points de chloration de l’eau assurent la disponibilité de l’eau potable aux populations sinistrés d’Uvira Briefing Humanitaire hebdomadaire Bukavu, 8 mai 2020 Coronavirus: aperçu national de l’épidémie • 23 cas confirmés au Kongo Central le 05 mai 2020 • Depuis le début de l’épidémie (10 mars 2020), 897 cas confirmés, 119 guéris et 36 décès . • 16 nouvelles personnes guéries en date du 07 mai • Les 7 provinces touchées : • • Kinshasa : 844 cas ; • Kongo Central : 29 cas ; • Haut-Katanga : 10 cas ; • Nord-Kivu : 7 cas ; • Sud-Kivu : 4 cas ; • Ituri : 2 cas ; • Kwilu : 1 cas. • ROUGEOLE : • 50 nouveaux cas de rougeole sur les deux dernières semaines, soit un cumul de 1 792 cas de janvier à début mai; • Une baisse de moitié par rapport aux deux semaines précédentes. Sud-Kivu • Fizi, Minova, Bunyakiri et Kalole restent en tête du nombre de Profil cas • Zéro décès de rougeole depuis au moins 4 semaines épidémiologique • CHOLERA: • 244 nouveaux cas enregistrés les deux dernières semaines, ce qui amène le total provincial à 2 323 cas de janvier à début mai • Zéro décès depuis deux semaines; ce qui dénote une certaine efficacité dans la prise en charge médicale. • Augmentation du nombre de cas à Fizi, Minova, Bagira et Idjwi, Katana et Kadutu (par ordre d’importance) • 08 nouveaux cas à Uvira; 07 cas en S17 et 01 seul cas en S18; ce qui fait un tableau épidémiologique relativement sous contrôle dans le contexte d’inondation • Paludisme • Plus -

Ocha Drc Population Movements in Eastern Dr Congo October – December 2009

Population Movements in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo OCHA DRC POPULATION MOVEMENTS IN EASTERN DR CONGO OCTOBER – DECEMBER 2009 January 2010 1 Population Movements in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo 1. OVERVIEW The humanitarian situation and movement of populations in 2009 have been heavily influenced by military operations and the still prevailing insecurity in a number of areas in the eastern provinces. Between January 20 and February 25 2009, the Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo (FARDC) and the Rwanda Defence Forces (RDF) conducted joint operations (Umoja Wetu) in North Kivu against the Forces Démocratiques pour le Liberation du Rwanda (FDLR). In March 2009 a second military operation (Kimia II) was launched in North Kivu and South Kivu. Lubero, Rutshuru, Masisi and Walikale are the territories in North Kivu where major displacements have been reported since March 2009. In South Kivu the most affected areas are Kalehe, Uvira and Shabunda. The attacks carried out by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a Ugandan militia, in the Orientale province since September 2008 have spread from the Haut Uele district to the Bas Uele in 2009. The population is victim of atrocities and acts of extreme violence: killings, rapes, kidnapping and looting leading to population displacements in many locations of the districts. N. IDPs per Province 800 000 767 399 730 941 700 000 600 000 Haut Uele 500 000 Bas Uele Ituri North Kivu 400 000 South Kivu Equateur 239 210 Katanga 300 000 165 472 200 000 58 937 60 000 100 000 14 000 0 Note: Ituri, Haut Uele and Bas Uele are districts of the Orientale province During the reporting period (October ‐ December 2009) some displacements have been reported in the Katanga province where about 14.000 people have moved from South Kivu due to the military operations in the area bordering Katanga. -

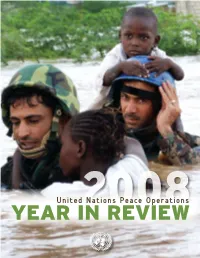

Year in Review 2008

United Nations Peace Operations YEAR IN2008 REVIEW asdf TABLE OF CONTENTS 12 ] UNMIS helps keep North-South Sudan peace on track 13 ] MINURCAT trains police in Chad, prepares to expand 15 ] After gaining ground in Liberia, UN blue helmets start to downsize 16 ] Progress in Côte d’Ivoire 18 ] UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea is withdrawn 19 ] UNMIN assists Nepal in transition to peace and democracy 20 ] Amid increasing insecurity, humanitarian and political work continues in Somalia 21 ] After nearly a decade in Kosovo, UNMIK reconfigures 23 ] Afghanistan – Room for hope despite challenges 27 ] New SRSG pursues robust UN mandate in electoral assistance, reconstruction and political dialogue in Iraq 29 ] UNIFIL provides a window of opportunity for peace in southern Lebanon 30 ] A watershed year for Timor-Leste 33 ] UN continues political and peacekeeping efforts in the Middle East 35 ] Renewed hope for a solution in Cyprus 37 ] UNOMIG carries out mandate in complex environment 38 ] DFS: Supporting peace operations Children of Tongo, Massi, North Kivu, DRC. 28 March 2008. UN Photo by Marie Frechon. Children of Tongo, 40 ] Demand grows for UN Police 41 ] National staff make huge contributions to UN peace 1 ] 2008: United Nations peacekeeping operations observes 60 years of operations 44 ] Ahtisaari brings pride to UN peace efforts with 2008 Nobel Prize 6 ] As peace in Congo remains elusive, 45 ] Security Council addresses sexual violence as Security Council strengthens threat to international peace and security MONUC’s hand [ Peace operations facts and figures ] 9 ] Challenges confront new peace- 47 ] Peacekeeping contributors keeping mission in Darfur 48 ] United Nations peacekeeping operations 25 ] Peacekeepers lead response to 50 ] United Nations political and peacebuilding missions disasters in Haiti 52 ] Top 10 troop contributors Cover photo: Jordanian peacekeepers rescue children 52 ] Surge in uniformed UN peacekeeping personnel from a flooded orphanage north of Port-au-Prince from1991-2008 after the passing of Hurricane Ike. -

Rwanda's Support to the March 23 Movement (M23)

Opinion Beyond the Single Story: Rwanda’s Support to the March 23 Movement (M23) Alphonse Muleefu* Introduction Since the news broke about the mutiny of some of the Congolese Armed Forces - Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo (FARDC) in April 2012 and their subsequent creation of the March 23 Movement (M23), we have been consistently supplied with one story about the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). A story that puts much emphasis on allegations that the government of Rwanda and later to some lesser extent that of Uganda are supporting M23 against the government of the DRC. This narrative was reinforced when the UN Group of Experts for the DRC (GoE) issued an Addendum of 48 pages on June 25, 20121 making allegations similar to those already made in Human Rights Watch’s (HRW) report of June 3, 20122, that the government of Rwanda was providing direct support in terms of recruitment, encouraging desertion of FARDC soldiers, providing weapons, ammunitions, intelligence, political advice to the M23, violating measures concerning the freezing of assets and collaborating with certain individuals. In response, the government of Rwanda issued a 131-page rebuttal on July 27, 2012, in which it denied all allegations and challenged the evidence given in support of each claim.3 On November 15, 2012, the GoE submitted its previously leaked report in which, in addition to the allegations made earlier, it claimed that the effective commander of M23 is Gen. James Kabarebe, Rwanda’s Minister of Defence, and that the senior officials of the government of Uganda had provided troop reinforcements, supplied weapons, offered technical assistance, joint planning, political advice and external relations.4 The alleged support provided by Ugandan officials was described as “subtle but crucial”, and the evidence against Rwanda was described as “overwhelming and compelling”. -

Executive Summary

Monthly Protection Monitoring Report – North Kivu September 2015 Executive Summary 2845 incidents have been recorded in September 2015. The number has decreased by 6,3% compared to August 2015 pendant, when 3037 incidents were reported. The territory Incidents per territory of Rutshuru has had the BENI 369 highest LUBERO 369 number of MASISI 639 incidents in NYIRAGONGO 133 September RUTSHURU 919 2015 WALIKALE 416 TOTAL 2845 Incidents per Incidents per alleged perpetrator category of victim Nombre des cas par type d’incident The majority of incidents in September 2015 were violations to the right of property and liberty PROTECTION MONITORING PMS Province du Nord Kivu 2 | UNHCR Protection Monitoring Nor th K i v u – Sept. Monthly Report PROTECTION MONITORING PMS Province du Nord Kivu I. Summary of main protection concerns Throughout September 2015, the PMS has registered 59,8% less internal displacement than in August 2015. This decrease can be justified by the relative calm perceived in significant displacement areas. On 17 September 2015, alleged NDC Cheka members pillaged Kalehe village to the Northeast of Bunyatenge and kidnapped around 30 people that were forced to transport the stolen goods to Mwanza and Mutiri, in Lubero territory. II. Protection context by territory MASISI The security situation in Masisi was characterised by clashes between FARDC and FDLR, between two different factions of FDDH (FDDH/Tuombe and FDDH/Mugwete) and between FARDC and APCLS. These conflicts have led to the massive displacement of the population from the areas affected by fighting followed by looting, killings and other violations. In Bibwe, around 400 families were displaced, among which 72 households are staying in a church and a school in Bibwe and around 330 families created a new site, accessible by car, around 2km from the Bibwe site. -

Of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO

Assessing the of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO REPORT 3/2019 Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2019 ISBN: 978-82-7002-346-2 Any views expressed in this publication are those of the author. Tey should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. Te text may not be re-published in part or in full without the permission of NUPI and the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: effectivepeaceops.net | www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 99 40 50 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 Assessing the Efectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC (MONUC-MONUSCO) Lead Author Dr Alexandra Novosseloff, International Peace Institute (IPI), New York and Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo Co-authors Dr Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Prof. Tomas Mandrup, Stellenbosch University, South Africa, and Royal Danish Defence College, Copenhagen Aaron Pangburn, Social Science Research Council (SSRC), New York Data Contributors Ryan Rappa and Paul von Chamier, Center on International Cooperation (CIC), New York University, New York EPON Series Editor Dr Cedric de Coning, NUPI External Reference Group Dr Tatiana Carayannis, SSRC, New York Lisa Sharland, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra Dr Charles Hunt, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, Australia Adam Day, Centre for Policy Research, UN University, New York Cover photo: UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti UN Photo/ Abel Kavanagh Contents Acknowledgements 5 Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 13 Te effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC across eight critical dimensions 14 Strategic and Operational Impact of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Constraints and Challenges of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Current Dilemmas 19 Introduction 21 Section 1. -

620290Wp0democ0box036147

Public Disclosure Authorized WORLD DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2011 BACKGROUND CASE STUDY EMOCRATIC EPUBLIC OF THE ONGO Public Disclosure Authorized D R C Tony Gambino March 2, 2011 (Final Revisions Received) The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the author. They do not necessarily represent the views of the World Development Report 2011 team, the World Public Disclosure Authorized Bank and its affiliated organizations, or those of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent Tony Gambino has worked on development and foreign policy issues for more than thirty years. For the last fourteen years, he has concentrated on the problems of fragile states, with a special focus on the states of Central Africa. He coordinated USAID’s re-engagement in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in 1997 and served there as USAID Mission Director from 2001-2004. He began his work in the Congo in 1979. The author wishes to thank Gérard Prunier, René Lemarchand, Ivor Fung (Director of the UN Regional Centre for Peace and Disarmament in Africa), Rachel Locke, (Head, Africa Team, Office for Conflict Mitigation and Management, Bureau for Africa, USAID), and Thierry Vircoulon (Project Director, Central Africa, International Crisis Group) for their thoughtful, insightful comments. The paper was greatly improved as a result of their questions, concerns, and comments. Remaining flaws are due to the author’s own analytical shortcomings. This paper was largely Public Disclosure Authorized completed in early 2010. Therefore, it does not include information on or analysis of the change from MONUC to MONUSCO or other important events that occurred later in 2010 or in early 2011. -

DR-CONGO December 2013

COUNTRY REPORT: DR-CONGO December 2013 Introduction: other provinces are also grappling with consistently high levels of violence. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DR-Congo) is the sec- ond most violent country in the ACLED dataset when Likewise, in terms of conflict actors, recent international measured by the number of conflict events; and the third commentary has focussed very heavily on the M23 rebel most fatal over the course of the dataset’s coverage (1997 group and their interactions with Congolese military - September 2013). forces and UN peacekeepers. However, while ACLED data illustrates that M23 has constituted the most violent non- Since 2011, violence levels have increased significantly in state actor in the country since its emergence in April this beleaguered country, primarily due to a sharp rise in 2012, other groups including Mayi Mayi militias, FDLR conflict in the Kivu regions (see Figure 1). Conflict levels rebels and unidentified armed groups also represent sig- during 2013 to date have reduced, following an unprece- nificant threats to security and stability. dented peak of activity in late 2012 but this year’s event levels remain significantly above average for the DR- In order to explore key dynamics of violence across time Congo. and space in the DR-Congo, this report examines in turn M23 in North and South Kivu, the Lord’s Resistance Army Across the coverage period, this violence has displayed a (LRA) in northern DR-Congo and the evolving dynamics of very distinct spatial pattern; over half of all conflict events Mayi Mayi violence across the country. The report then occurred in the eastern Kivu provinces, while a further examines MONUSCO’s efforts to maintain a fragile peace quarter took place in Orientale and less than 10% in Ka- in the country, and highlights the dynamics of the on- tanga (see Figure 2). -

Dismissed! Victims of 2015-2018 Brutal Crackdowns in the Democratic Republic of Congo Denied Justice

DISMISSED! VICTIMS OF 2015-2018 BRUTAL CRACKDOWNS IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DENIED JUSTICE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: “Dismissed!”. A drawing by Congolese artist © Justin Kasereka (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 62/2185/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 2. METHODOLOGY 9 3. BACKGROUND: POLITICAL CRISIS 10 3.1 ATTEMPTS TO AMEND THE CONSTITUTION 10 3.2 THE « GLISSEMENT »: THE LONG-DRAWN-OUT ELECTORAL PROCESS 11 3.3 ELECTIONS AT LAST 14 3.3.1 TIMELINE 15 4. VOICES OF DISSENT MUZZLED 19 4.1 ARBITRARY ARRESTS, DETENTIONS AND SYSTEMATIC BANS ON ASSEMBLIES 19 4.1.1 HARASSMENT AND ARBITRARY ARRESTS OF PRO-DEMOCRACY ACTIVISTS AND OPPONENTS 20 4.1.2 SYSTEMATIC AND UNLAWFUL BANS ON ASSEMBLY 21 4.2 RESTRICTIONS OF THE RIGHT TO SEEK AND RECEIVE INFORMATION 23 5. -

Virunga Landscape

23. Virunga Landscape Th e Landscape in brief Coordinates: 1°1’29’’N – 1°44’21’’S – 28°56’11’’E – 30°5’2’’E. Area: 15,155 km2 Elevation: 680–5,119 m Terrestrial ecoregions: Ecoregion of the Afroalpine barrens of Ruwenzori-Virunga Ecoregion of the Afromontane forests of the Albertine Rift Ecoregion of the forest-savannah mosaic of Lake Victoria Aquatic ecoregions: Mountains of the Albertine Rift Lakes Kivu, Edward, George and Victoria Protected areas: Virunga National Park, DRC, 772,700 ha, 1925 Volcans National Park, Rwanda, 16,000 ha, 1925 Rutshuru Hunting Domain, 64,200 ha, 1946 added Bwindi-Impenetrable National Park situ- ated a short distance away from the volcanoes in southwest Uganda. Th is complex functions as a single ecosystem and many animals move across the borders, which permits restoration of the populations1. Physical environment Relief and altitude Th e Landscape is focused on the central trough of the Albertine Rift, occupied by Lake Figure 23.1. Map of Virunga Landscape (Sources: CARPE, Edward (916 m, 2,240 km²), and vast plains DFGFI, JRC, SRTM, WWF-EARPO). at an altitude of between 680 and 1,450 m. Its western edge stretches along the eastern bluff of Location and area the Mitumba Mountain Range forming the west- ern ridge of the rift. In the northeast, it includes he Virunga Landscape covers 15,155 km² the western bluff of the Ruwenzori horst (fault Tand includes two contiguous national parks, block) with its active glaciers, whose peak reaches Virunga National Park in DRC and Volcans a height of 5,119 m and whose very steep relief National Park in Rwanda, the Rutshuru Hunting comprises numerous old glacial valleys (Figure Zone and a 10 km-wide strip at the edge of the 23.2). -

Le Président Du Conseil De Sécurité Présente

Le Président du Conseil de sécurité présente ses compliments aux membres du Conseil et a l'honneur de transmettre, pour information, le texte d'une lettre datée du 2 juin 2020, adressée au Président du Conseil de sécurité, par le Groupe d’experts sur la République démocratique du Congo reconduit suivant la résolution 2478 (2019) du Conseil de sécurité, ainsi que les pièces qui y sont jointes. Cette lettre et les pièces qui y sont jointes seront publiées comme document du Conseil de sécurité sous la cote S/2020/482. Le 2 juin 2020 The President of the Security Council presents his compliments to the members of the Council and has the honour to transmit herewith, for their information, a copy of a letter dated 2 June 2020 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo extended pursuant to Security Council resolution 2478 (2019) addressed to the President of the Security Council, and its enclosures. This letter and its enclosures will be issued as a document of the Security Council under the symbol S/2020/482. 2 June 2020 UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES POSTAL ADDRESS-ADRESSE POSTALE: UNITED NATIONS, N.Y. 10017 CABLE ADDRESS -ADRESSE TELEGRAPHIQUE: UNATIONS NEWYORK REFERENCE: S/AC.43/2020/GE/OC.171 2 juin 2020 Monsieur Président, Les membres du Groupe d’experts sur la République démocratique du Congo, dont le mandat a été prorogé par le Conseil de sécurité dans sa résolution 2478 (2019), ont l’honneur de vous faire parvenir leur rapport final, conformément au paragraphe 4 de ladite résolution. -

KAS International Reports 06/2013

56 KAS INTERNATIONAL REPORTS 6|2013 M23 REBELLION A FURTHER CHAPTER IN THE VIOLENCE IN EASTERN CONGO Steffen Krüger Steffen Krüger is Resident Representa- In recent years, the provinces of North Kivu and South tive of the Konrad- Kivu in the east of the Democratic Republic of the Congo Adenauer- Stiftung have once again become the epicentre of various conflicts in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. in the African Great Lakes Region. The two provinces and their population of ten million were affected particularly strongly by the three Congo Wars between 1996 and 2006. For years they have been the scene of looting, indiscrimi- nate killing and other crimes committed by various parties to the conflict. The region is very densely populated and rich in mineral resources. The reserves of gold, diamonds, tin, coltan1 and other raw materials are worth hundreds of billions of euros. In April 2012, the M23 Rebellion2 began with the mutiny of 600 Congolese soldiers, bringing a new wave of violence and destruction to the region. Many women, children and men fell victim to the conflict and over 900,000 people had to flee their homes yet again. Nobody knows the precise figures because many are left to their own devices and have hardly any access to assistance. The fighting has now stopped, but the insecurity of not knowing whether a new conflict may break out remains. Various national and inter- national actors have analysed the events during the past few months and discussed solutions for a lasting peace. 1 | Coltan is an ore, which is mainly processed to extract the metal tantalum.