Of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNHCR Republic of Congo Fact Sheet

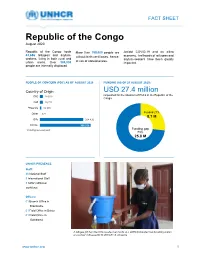

FACT SHEET Republic of the Congo August 2020 Republic of the Congo hosts More than 155,000 people are Amidst COVID-19 and an ailing 43,656 refugees and asylum- without birth certificates, hence, economy, livelihoods of refugees and seekers, living in both rural and asylum-seekers have been greatly at risk of statelessness. urban areas. Over 304,000 impacted. people are internally displaced PEOPLE OF CONCERN (POC) AS OF AUGUST 2020 FUNDING (AS OF 25 AUGUST 2020) Country of Origin USD 27.4 million requested for the situation of PoCs in the Republic of the DRC 20 810 Congo CAR 20,722 *Rwanda 10 565 Funded 27% Other 421 8.1 M IDPs 304 430 TOTAL: 356 926 * Including non-exempted Funding gap 73% 25.8 M UNHCR PRESENCE Staff: 46 National Staff 9 International Staff 8 IUNV (affiliated workforce) Offices: 01 Branch Office in Brazzaville 01 Field Office in Betou 01 Field Office in Gamboma A refugee girl from the DRC washes her hands at a UNHCR-installed handwashing station at a school in Brazzaville © UNHCR / S. Duysens www.unhcr.org 1 FACT SHEET > Republic of the Congo / August 2020 Working with Partners ■ Aligning with the Global Compact on Refugees (GCR), UNHCR in the Republic of the Congo (RoC) has diversified its partnership base to include five implementing partners, comprising local governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), as well as international NGOs. ■ The National Committee for Assistance to Refugees (CNAR), is UNHCR’s main governmental partner, covering general refugee issues, particularly Refugee Status Determination (RSD). Other specific governmental partners include the Ministry of Social and Humanitarian Affairs (MASAH), the Ministries of Justice and Interior (for judicial issues and policies on issues related to statelessness and civil status registration), and the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH). -

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) Reports Children in Need of Humanitarian Assistance Its First COVID-19 Confirmed Case

ef Democratic Republic of the Congo Humanitarian Situation Report No. 03 © UNICEF/UN0231603/Herrmann Reporting Period: March 2020 Highlights Situation in Numbers 9,100,000 • 10 March, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) reports children in need of humanitarian assistance its first COVID-19 confirmed case. As of 31 March 2020, 109 confirmed cases have been recorded, of which 9 deaths and 3 (OCHA, HNO 2020) recovered patients have been reported. During the reporting period, the virus has affected the province of Kinshasa and North Kivu 15,600,000 people in need • In addition to UNICEF’s Humanitarian Action for Children (HAC) (OCHA, HNO 2020) 2020 appeal of $262 million, UNICEF’s COVID-19 response plan has a funding appeal of $58 million to support UNICEF’s response 5,010,000 in WASH/Infection Prevention and Control, risk communication, and community engagement. UNICEF’s response to COVID-19 Internally displaced people can be found on the following link (HNO 2020) 6,297 • During the reporting period, 26,789 in cholera-prone zones and cases of cholera reported other epidemic-affected areas benefiting from prevention and since January response WASH packages (Ministry of Health) UNICEF’s Response and Funding Status UNICEF Appeal 2020 9% US$ 262 million 11% 21% Funding Status (in US$) 15% Funds Carry- received forward, 10% $5.5 M $28.8M 10% 49% 21% 15% Funding gap, 3% $229.3M 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% 1 Funding Overview and Partnerships UNICEF appeals for US$ 262M to sustain the provision of humanitarian services for women and children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). -

Actor Heatmap

2017 Q3 Report CONTENTS 1. Results & Overall Progress 2. Sectors 3. Regions 4. Cross-Cutting Sectors, Operations & Management 5. Business Development Services 6. Markets in Crisis 7. Women’s Economic Empowerment INTRODUCTION The third quarter was another busy one at ELAN RDC, as the programme balanced a mid-term evaluation and data verification process in addition to ongoing implementation. A number of new consultants contributed to increased activity for the technical team during the quarter, resulting in concrete workstreams on business development services (BDS), the launch of scoping to replicate existing interventions in conflict-affected Kasai Central, and a renewed focus on gender through increased support from our senior gender adviser. A number of large partnerships were finalised thanks to agreement with DFID on an improved non-objection review process, however, several large partnerships remained delayed due to multiple factors including increasing unstable market conditions. Partnerships in the energy and agriculture sectors were finalised during the quarter, while several partnerships in the financial sector faced delays. The programme has initiated a drive to increase and improve communications of programme results, resulting in an increase in visibility across various media. The launch of the Congo Coffee Atlas, completion of research for The Africa Seed Access Index (TASAI), meeting with mobile network operators to establish a lobbying platform and the finalisation of the contract for a renewable energy marketing campaign are all examples of activities through which ELAN RDC has made more market information available to the broader private sector. More details about third quarter results are found in the following slides. -

Eradicating Ebola: Lessons Learned and Medical Advancements Hearing

ERADICATING EBOLA: LESSONS LEARNED AND MEDICAL ADVANCEMENTS HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA, GLOBAL HEALTH, GLOBAL HUMAN RIGHTS, AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JUNE 4, 2019 Serial No. 116–44 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/, http://docs.house.gov, or http://www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 36–558PDF WASHINGTON : 2019 COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York, Chairman BRAD SHERMAN, California MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas, Ranking GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York Member ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia STEVE CHABOT, Ohio THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida JOE WILSON, South Carolina KAREN BASS, California SCOTT PERRY, Pennsylvania WILLIAM KEATING, Massachusetts TED S. YOHO, Florida DAVID CICILLINE, Rhode Island ADAM KINZINGER, Illinois AMI BERA, California LEE ZELDIN, New York JOAQUIN CASTRO, Texas JIM SENSENBRENNER, Wisconsin DINA TITUS, Nevada ANN WAGNER, Missouri ADRIANO ESPAILLAT, New York BRIAN MAST, Florida TED LIEU, California FRANCIS ROONEY, Florida SUSAN WILD, Pennsylvania BRIAN FITZPATRICK, Pennsylvania DEAN PHILLIPS, Minnesota JOHN CURTIS, Utah ILHAN OMAR, Minnesota KEN BUCK, Colorado COLIN ALLRED, Texas RON WRIGHT, Texas ANDY LEVIN, Michigan GUY RESCHENTHALER, Pennsylvania ABIGAIL SPANBERGER, Virginia TIM BURCHETT, Tennessee CHRISSY HOULAHAN, Pennsylvania GREG PENCE, Indiana -

Reconstruction Under Fire: Case Studies and Further Analysis Of

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Reconstruction Under Fire Case Studies and Further Analysis of Civil Requirements A COMPANION VOLUME TO RECONSTRUCTION UNDER FIRE: UNIFYING CIVIL AND MILITARY COUNTERINSURGENCY Brooke Stearns Lawson, Terrence K. -

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS for the DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20

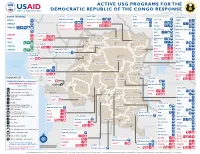

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20 BAS-UELE HAUT-UELE ITURI S O U T H S U D A N COUNTRYWIDE NORTH KIVU OCHA IMA World Health Samaritan’s Purse AIRD Internews CARE C.A.R. Samaritan’s Purse Samaritan’s Purse IMA World Health IOM UNHAS CAMEROON DCA ACTED WFP INSO Medair FHI 360 UNICEF Samaritan’s Purse Mercy Corps IMA World Health NRC NORD-UBANGI IMC UNICEF Gbadolite Oxfam ACTED INSO NORD-UBANGI Samaritan’s WFP WFP Gemena BAS-UELE Internews HAUT-UELE Purse ICRC Buta SCF IOM SUD-UBANGI SUD-UBANGI UNHAS MONGALA Isiro Tearfund IRC WFP Lisala ACF Medair UNHCR MONGALA ITURI U Bunia Mercy Corps Mercy Corps IMA World Health G A EQUATEUR Samaritan’s NRC EQUATEUR Kisangani N Purse WFP D WFPaa Oxfam Boende A REPUBLIC OF Mbandaka TSHOPO Samaritan’s ATLANTIC NORTH GABON THE CONGO TSHUAPA Purse TSHOPO KIVU Lake OCEAN Tearfund IMA World Health Goma Victoria Inongo WHH Samaritan’s Purse RWANDA Mercy Corps BURUNDI Samaritan’s Purse MAI-NDOMBE Kindu Bukavu Samaritan’s Purse PROGRAM KEY KINSHASA SOUTH MANIEMA SANKURU MANIEMA KIVU WFP USAID/BHA Non-Food Assistance* WFP ACTED USAID/BHA Food Assistance** SA ! A IMA World Health TA N Z A N I A Kinshasa SH State/PRM KIN KASAÏ Lusambo KWILU Oxfam Kenge TANGANYIKA Agriculture and Food Security KONGO CENTRAL Kananga ACTED CRS Cash Transfers For Food Matadi LOMAMI Kalemie KASAÏ- Kabinda WFP Concern Economic Recovery and Market Tshikapa ORIENTAL Systems KWANGO Mbuji T IMA World Health KWANGO Mayi TANGANYIKA a KASAÏ- n Food Vouchers g WFP a n IMC CENTRAL y i k -

Monusco and Drc Elections

MONUSCO AND DRC ELECTIONS With current volatility over elections in Democratic Republic of the Congo, this paper provides background on the challenges and forewarns of MONUSCO’s inability to quell large scale electoral violence due to financial and logistical constraints. By Chandrima Das, Director of Peacekeeping Policy, UN Foundation. OVERVIEW The UN Peacekeeping Mission in the Dem- ment is asserting their authority and are ready to ocratic Republic of the Congo, known by the demonstrate their ability to hold credible elec- acronym “MONUSCO,” is critical to supporting tions. DRC President Joseph Kabila stated during peace and stability in the Democratic Republic the UN General Assembly high-level week in of the Congo (DRC). MONUSCO battles back September 2018: “I now reaffirm the irreversible militias, holds parties accountable to the peace nature of our decision to hold the elections as agreement, and works to ensure political stabil- planned at the end of this year. Everything will ity. Presidential elections were set to take place be done in order to ensure that these elections on December 23 of this year, after two years are peaceful and credible.” of delay. While they may be delayed further, MONUSCO has worked to train security ser- due to repressive tactics by the government, vices across the country to minimize excessive the potential for electoral violence and fraud is use of force during protests and demonstrations. high. In addition, due to MONUSCO’s capacity However, MONUSCO troops are spread thin restraints, the mission will not be able to protect across the entire country, with less than 1,000 civilians if large scale electoral violence occurs. -

E Story of UNMIL

e story of UNMIL United Nations Mission in Liberia >>Return to table of contents<< >>Return to table of contents<< The story of UNMIL >>Return to table of contents<< Dedication This book is dedicated, first and foremost, to the people of Liberia, whose resilience and determination have lifted their country from the ashes of war to attain 14 years of peace. It is also dedicated to all United Nations personnel who have worked in Liberia since 2003, and those colleagues who lost their lives while serving with UNMIL--all of whom made invaluable sacrifices, leaving behind their families and loved ones to help consolidate and support the peace that Liberians enjoy today. The flags of the United Nations and Liberia fly side by side at the UNMIL Headquarters in Monrovia, Liberia. Photo: Staton Winter | UNMIL | 13 May 11 >>Return to table of contents<< Table of Contents Dedication ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 António Guterres, Secretary-General of the United Nations (2016-) .....................................................................................6 Preface ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 His Excellency Mr. George Manneh Weah, President of the Republic of Liberia (2018-) .....................................................8 -

Banyamulenge, Congolese Tutsis, Kinshasa

Response to Information Request COD103417.FE Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada www.irb-cisr.gc.ca Français Home Contact Us Help Search canada.gc.ca Home > Research > Responses to Information Requests RESPONSES TO INFORMATION REQUESTS (RIRs) New Search | About RIRs | Help The Board 31 March 2010 About the Board COD103417.FE Biographies Organization Chart Democratic Republic of the Congo: The treatment of the Banyamulenge, or Congolese Tutsis, living in Kinshasa and in the provinces of North Kivu and South Employment Kivu Legal and Policy Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa References Publications Situation of the Banyamulenge in Kinshasa Tribunal Several sources consulted by the Research Directorate indicated that the Refugee Protection Banyamulenge, or Congolese Tutsis, do not have any particular problems in Division Kinshasa (Journalist 9 Mar. 2010; Le Phare 22 Feb. 2010; VSV 18 Feb. 2010). Immigration Division During a 18 February 2010 telephone interview with the Research Directorate, Immigration Appeal a representative of Voice of the Voiceless for the Defence of Human Rights (La Voix Division des sans voix pour les droits de l'homme, VSV), a human rights non-governmental Decisions organization (NGO) dedicated to defending human rights in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) (VSV n.d.), stated that his organization has never Forms been aware of [translation] “a case in which a person was mistreated by the Statistics authorities or the Kinshasa population in general” solely because that person was Research of Banyamulenge ethnic origin. Moreover, in correspondence sent to the Research Directorate on 22 February 2010, the manager of the Kinshasa newspaper Le Phare Research Program wrote the following: National Documentation [translation] Packages There are no problems where the Banyamulenge-or Tutsis-in Kinshasa are Issue Papers and concerned. -

Togo an Election Tainted by Escalating Violence

Public amnesty international TOGO AN ELECTION TAINTED BY ESCALATING VIOLENCE AI Index: AFR 57/005/2003 6 June 2003 INTERNATIONAL SECRETARIAT, 1 EASTON STREET, LONDON WC1X 0DW, UNITED KINGDOM TOGO : AN ELECTION TAINTED BY ESCALATING VIOLENCE The presidential election that took place in Togo on 1 June 2003 resulted, as many independent observers feared, in clashes between opposition supporters and the security forces, who made arrests and used force to suppress demonstrations and discontent in several parts of the country. During the last month, the security forces have arrested about forty people who the military suspect of voting for opposition candidates or inciting other people to do so. One person was shot in the back in an extrajudicial manner by a member of the security forces. The man was escaping on a motor bike when he was shot. Another person was seriously wounded in this incident. Security forces are on patrol throughout the country, especially in Lomé. Passers-by, some of whom were suspected of being close to the opposition, have been stopped in the street by the security forces and beaten up. The authorities have also put pressure on journalists to publish only the results announced by the Commission électorale nationale indépendante (CENI) 1 , National Independent Electoral Commission. On 4 June 2003, CENI officially declared the winner of the election to be the outgoing president, Gnassingbé Eyadéma, in power since 1967. Two days previously, two opposition candidates, Emmanuel Bob Akitani and Maurice Dahuku Péré, representatives, of l’Union des forces du changement (UFC) the Union of Forces for Change and the Pacte socialiste pour le renouveau (PSR), Socialist Pact for Renewal respectively, proclaimed themselves winners of the election. -

The Chair of the African Union

Th e Chair of the African Union What prospect for institutionalisation? THE EVOLVING PHENOMENA of the Pan-African organisation to react timeously to OF THE CHAIR continental and international events. Th e Moroccan delegation asserted that when an event occurred on the Th e chair of the Pan-African organisation is one position international scene, member states could fail to react as that can be scrutinised and defi ned with diffi culty. Its they would give priority to their national concerns, or real political and institutional signifi cance can only be would make a diff erent assessment of such continental appraised through a historical analysis because it is an and international events, the reason being that, con- institution that has evolved and acquired its current trary to the United Nations, the OAU did not have any shape and weight through practical engagements. Th e permanent representatives that could be convened at any expansion of the powers of the chairperson is the result time to make a timely decision on a given situation.2 of a process dating back to the era of the Organisation of Th e delegation from Sierra Leone, a former member African Unity (OAU) and continuing under the African of the Monrovia group, considered the hypothesis of Union (AU). the loss of powers of the chairperson3 by alluding to the Indeed, the desirability or otherwise of creating eff ect of the possible political fragility of the continent on a chair position had been debated among members the so-called chair function. since the creation of the Pan-African organisation. -

Dismissed! Victims of 2015-2018 Brutal Crackdowns in the Democratic Republic of Congo Denied Justice

DISMISSED! VICTIMS OF 2015-2018 BRUTAL CRACKDOWNS IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DENIED JUSTICE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: “Dismissed!”. A drawing by Congolese artist © Justin Kasereka (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 62/2185/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 2. METHODOLOGY 9 3. BACKGROUND: POLITICAL CRISIS 10 3.1 ATTEMPTS TO AMEND THE CONSTITUTION 10 3.2 THE « GLISSEMENT »: THE LONG-DRAWN-OUT ELECTORAL PROCESS 11 3.3 ELECTIONS AT LAST 14 3.3.1 TIMELINE 15 4. VOICES OF DISSENT MUZZLED 19 4.1 ARBITRARY ARRESTS, DETENTIONS AND SYSTEMATIC BANS ON ASSEMBLIES 19 4.1.1 HARASSMENT AND ARBITRARY ARRESTS OF PRO-DEMOCRACY ACTIVISTS AND OPPONENTS 20 4.1.2 SYSTEMATIC AND UNLAWFUL BANS ON ASSEMBLY 21 4.2 RESTRICTIONS OF THE RIGHT TO SEEK AND RECEIVE INFORMATION 23 5.