Eradicating Ebola: Lessons Learned and Medical Advancements Hearing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO

Assessing the of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO REPORT 3/2019 Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2019 ISBN: 978-82-7002-346-2 Any views expressed in this publication are those of the author. Tey should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. Te text may not be re-published in part or in full without the permission of NUPI and the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: effectivepeaceops.net | www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 99 40 50 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 Assessing the Efectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC (MONUC-MONUSCO) Lead Author Dr Alexandra Novosseloff, International Peace Institute (IPI), New York and Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo Co-authors Dr Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Prof. Tomas Mandrup, Stellenbosch University, South Africa, and Royal Danish Defence College, Copenhagen Aaron Pangburn, Social Science Research Council (SSRC), New York Data Contributors Ryan Rappa and Paul von Chamier, Center on International Cooperation (CIC), New York University, New York EPON Series Editor Dr Cedric de Coning, NUPI External Reference Group Dr Tatiana Carayannis, SSRC, New York Lisa Sharland, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra Dr Charles Hunt, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, Australia Adam Day, Centre for Policy Research, UN University, New York Cover photo: UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti UN Photo/ Abel Kavanagh Contents Acknowledgements 5 Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 13 Te effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC across eight critical dimensions 14 Strategic and Operational Impact of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Constraints and Challenges of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Current Dilemmas 19 Introduction 21 Section 1. -

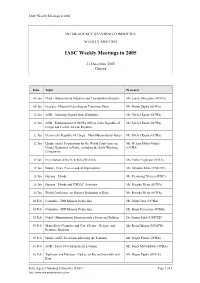

20051212-673, Weekly Meetings in 2005

IASC Weekly Meetings in 2005 INTER-AGENCY STANDING COMMITTEE WEEKLY MEETING IASC Weekly Meetings in 2005 21 December 2005 Geneva Date Topic Presenter 05 Jan Chad - Humanitarian Situation and Coordination Structure Ms. Lucia Alberghini (OCHA) 05 Jan Georgia - Mission Debriefing on Transition Phase Mr. Dusan Zupka (OCHA) 12 Jan AOB - Alarming Signals from Zimbabwe Mr. Michel Kassa (OCHA) 12 Jan AOB - Establishment of OCHA Offices in the Republic of Mr. Michel Kassa (OCHA) Congo and Central African Republic 12 Jan Democratic Republic of Congo - Main Humanitarian Issues Mr. Michel Kassa (OCHA) 12 Jan Update on the Preparations for the World Conference on Ms. Helena Molin-Valdes Diaster Reduction in Kobe, including the Early Warning (OCHA) Component 19 Jan Presentation of the New ReliefWeb Site Ms. Esther Vigneau (OCHA) 19 Jan Sudan - Peace Process and its Implications Mr. Sikander Khan (UNICEF) 26 Jan Guyana - Floods Mr. Flemming Nielsen (IFRC) 26 Jan Guyana - Floods and UNDAC Activities Mr. Ricardo Mena (OCHA) 26 Jan World Conference on Disaster Reduction in Kobe Mr. Ricardo Mena (OCHA) 02 Feb Columbia - IDD Mission Debriefing Mr. Mark Cutts (OCHA) 02 Feb Columbia - IDD Mission Debriefing Mr. Bjorn Pettersson (OCHA) 02 Feb Nepal - Humanitarian Situation with a Focus on Children Dr. Suomi Sakai (UNICEF) 09 Feb Mano River Countries and Cote d'Iviore - Refugee and Mr. Raouf Mazou (UNHCR) Returnee Situation 09 Feb Update on EU Decisions following the Tsunami Mr. Sergio Piazzi (OCHA) 16 Feb AOB - Latest Developments in Lebanon Mr. Jamie McGoldrick (OCHA) 16 Feb Tajikistan and Pakistan - Update on Recent Snowfalls and Mr. Dusan Zupka (OCHA) Rain Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Page 1 of 5 http://www.humanitarianinfo.org/iasc IASC Weekly Meetings in 2005 Date Topic Presenter 16 Feb Togo - Update on the Current Situation Mr. -

Informal Interactive Dialogues and Other Informal Meetings of the Security Council (As of 13 December 2019)

Informal Interactive Dialogues and Other Informal Meetings of the Security Council (as of 13 December 2019) DATE/ VENUE DESCRIPTIVE SUBJECT BRIEFERS NON‐SC / LISTED IN: NAME NON‐UN PARTICIPANTS JOURNAL SC ANNUAL POW REPORT 27 November 2019 Informal Peace consolidation in Abdoulaye Bathily, former head of the UN Regional Office for Central None NO NO N/A Conf. Rm. 7 interactive West Africa/UNOWAS Africa (UNOCA) and the author of the independent strategic review of dialogue the UN Office for West Africa and the Sahel (UNOWAS); Bintou Keita (Assistant Secretary‐General for Africa); Guillermo Fernández de Soto Valderrama (Permanent Representative of Colombia and Peace Building Commission Chair) 28 August 2019 Informal The situation in Burundi Michael Kingsley‐Nyinah (Director for Central and Southern Africa United Republic of NO NO N/A Conf. Rm. 6 interactive Division, DPPA/DPO), Jürg Lauber (Switzerland PR as Chair of PBC Tanzania dialogue Burundi configuration) 31 July 2019 Informal Peace and security in Amira Elfadil Mohammed Elfadil (AU Comissioner for Social Affairs), Democratic Republic NO NO N/A Conf. Room 7 interactive Africa (Ebola outbreak in David Gressly (Ebola Emergency Response Coordinator), Mark Lowcock of the Congo dialogue the DRC) (Under‐Secretary‐General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator), Michael Ryan (WHO Health Emergencies Programme Executive Director) 7 June 2019 Informal The situation in Libya Mr. Pedro Serrano, Deputy Secretary General of the European External none NO NO N/A Conf. Rm. 7 interactive (Resolution 2292 (2016) Action Service dialogue implementation) 21 March 2019 Informal The situation in the Joost R. Hiltermann (Program Director for Middle East & North Africa, NO NO N/A Conf. -

WHO's Response to the 2018–2019 Ebola Outbreak in North Kivu and Ituri, the Democratic Republic of the Congo

WHO's response to the 2018–2019 Ebola outbreak in North Kivu and Ituri, the Democratic Republic of the Congo Report to donors for the period August 2018 – June 2019 2 | 2018-2019 North Kivu and Ituri Ebola virus disease outbreak: WHO report to donors © World Health Organization 2019 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Ebola Virus Disease October 2014 • $12.00 US

SPECIAL DIGITAL ISSUE: Ebola Virus Disease October 2014 • $12.00 US EBOLA VIRUS DISEASE A Primer for Infection Preventionists Ebola Virus Disease: A Primer for Infection Preventionists By Kelly M. Pyrek ccording to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Ebola — previously known as AEbola hemorrhagic fever — is a rare and deadly disease caused by infection with one of the Ebola virus strains. Ebola can cause disease in humans and non- human primates. Ebola is caused by infection with a virus of the family Filoviridae, genus Ebolavirus. There Ebola, previously known are five identified Ebola virus species, four of which are known to cause disease in humans: Ebola virus as Ebola hemorrhagic (Zaire ebolavirus); Sudan virus (Sudan ebolavirus); fever, is a rare and Taï Forest virus (Taï Forest ebolavirus, formerly Côte d’Ivoire ebolavirus); and Bundibugyo virus (Bundibugyo deadly disease caused ebolavirus). The fifth, Reston virus (Reston ebolavirus), by infection with one of has caused disease in non-human primates, but not in humans. the Ebola virus strains. Ebola was first discovered in 1976 near the Ebola River in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Since then, outbreaks have appeared sporadically in Africa. The natural reservoir host of Ebola virus remains unknown; however, on the basis of evidence and the nature of similar viruses, researchers believe that the virus is animal-borne and that bats are the most likely reservoir. Four of the five virus strains occur in an animal host native to Africa. INFECTION CONTROL TODAY Ebola Virus Disease www.infectioncontroltoday.com 3 The Outbreak Situation at Home and Abroad: An Update As of Oct. -

S/2014/886 Security Council

United Nations S/2014/886 Security Council Distr.: General 16 December 2014 English Original: French Letter dated 11 December 2014 from the Permanent Representative of Mali to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council I have the honour to transmit herewith the conclusions of the third ministerial meeting of the coordination platform on strategies for the Sahel (see annex), which was held in Bamako on 18 November 2014. I should be grateful if you would have this letter and its annex circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Sékou Kassé Ambassador Permanent Representative 14-67359 (E) 181214 191214 *1467359* S/2014/886 Annex to the letter dated 11 December 2014 from the Permanent Representative of Mali to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council Third ministerial meeting of the coordination platform on strategies for the Sahel Conclusions [Bamako, 18 November 2014] 1. The third ministerial meeting of the coordination platform on strategies for the Sahel was held on 18 November 2014 at the Bamako International Conference Centre and was chaired by His Excellency Mr. Abdoulaye Diop, Minister for Foreign Affairs, African Integration and International Cooperation of the Republic of Mali, which currently holds the chairmanship of the Platform. 2. At the opening ceremony, a message from Mr. Ban Ki-moon, Secretary- General of the United Nations, was delivered by Ms. Hiroute Guebre Sellassie, Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for the Sahel. Statements were also made by Mr. Pierre Buyoya, High Representative of the African Union for Mali and the Sahel; Mr. -

S/PV.8584 the Situation Concerning the Democratic Republic of the Congo 24/07/2019

United Nations S/ PV.8584 Security Council Provisional Seventy-fourth year 8584th meeting Wednesday, 24 July 2019, 10 a.m. New York President: Mr. Meza-Cuadra ............................... (Peru) Members: Belgium ....................................... Mr. Pecsteen de Buytswerve China ......................................... Mr. Wu Haitao Côte d’Ivoire ................................... Mr. Ipo Dominican Republic .............................. Mr. Singer Weisinger Equatorial Guinea ............................... Mrs. Mele Colifa France ........................................ Mr. De Rivière Germany ...................................... Mr. Heusgen Indonesia. Mr. Djani Kuwait ........................................ Mr. Alotaibi Poland ........................................ Ms. Wronecka Russian Federation ............................... Mr. Polyanskiy South Africa ................................... Mr. Mabhongo United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland .. Mr. Hickey United States of America .......................... Ms. Norman-Chalet Agenda The situation concerning the Democratic Republic of the Congo Report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (S/2019/575) This record contains the text of speeches delivered in English and of the translation of speeches delivered in other languages. The final text will be printed in the Official Records of the Security Council. Corrections should be submitted to the original languages only. They should -

The Mali Migration Crisis at a Glance

THE MALI MIGRATION CRISIS AT A GLANCE March 2013 The Mali Migration Crisis at a Glance International Organization for Migration TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents 2 Introduction 3 I Mali Migration Picture Prior to the 2012 Crisis 4 1. Important and Complex Circular Migration Flows including Pastoralist Movements 4 2. Migration Routes through Mali: from smuggling to trafficking of people and goods 4 3. Internal Migration Trends: Increased Urbanization and Food Insecurity 4 4. Foreign Population in Mali: Centered on regional migration 4 5. Malians Abroad: A significant diaspora 5 II Migration Crisis in Mali: From January 2012 to January 2013 6 1. Large Scale Internal Displacement to Southern Cities 6 2. Refugee Flows to Neighbouring Countries 6 3. Other Crisis-induced Mobility Patterns and Flows 7 III Mobility Patterns since the January 2013 International Military Intervention 8 1. Internal and Cross-Border Displacement since January 2013 8 2. Movements and Intention of Return of IDPs 8 IV Addressing the Mali Migration Crisis through a Holistic Approach 10 1. Strengthening information collection and management 10 2. Continuing responding to the most pressing humanitarian needs 10 3. Carefully supporting return, reintegration and stabilization 10 4. Integrating a cross-border and regional approach 10 5. Investing in building resilience and peace 10 References 12 page 2 Introduction INTRODUCTION variety of sources, including data collected through the Com- mission on Population Movement led by IOM and composed MIGRATION CRISIS of two national government entities, several UN agencies, and a number of NGOs. In terms of structure it looks at the Mali migration picture before January 2012 (Part I); the migration IOM uses the term “migration crisis” as a way to crisis as it evolved between January 2012 and the January refer to and analyse the often large-scale and 2013 international military intervention (Part II); and the situa- unpredictable migration flows and mobility tion since the military intervention (Part III). -

Protection Cluster Digest

Protection Cluster Digest The Newsletter of The Global Protection Cluster - 5th Edition vol. 02/2013 Adding to the voices of IDPs: WHY OUR PROTECTION ADVOCACY MATTERS Special contributions: Humanitarian Coordinators on Protection and Advocacy Feature: DISPLACEMENT IN THE 21st CENTURY - KEEPING IDPs ON THE AGENDA Interview with Volker Turk, Director of International Protection, UNHCR © UNAMID / Albert González Farran • Voices from the Field: Special Contribution • News from clusters • Areas of Responsibilities • What’s Been Happening • News from your GPC Support Cell • Technical Briefings • Training and Learning • GPC Essential Contact List • and more... A WORD from the Global Protection Cluster Coordinator Dear Colleagues, So much has happened this past year in terms of protection advocacy that it seemed most appropriate to dedicate this newest edition of the DIGEST to share what these efforts have achieved. A particular focus of our collective advocacy has been to draw attention to the risks faced by internally displaced persons, and with reason: with a succession of humanitarian crises, notably inside Syria and the Central African Republic, and more recently in the Philippines, the number of forcefully displaced LOUISE AUBIN persons has never been greater. Responding to their critical protection and assistance needs is challenging enough, but to do this in a timely and appropriate manner particularly where IDPs are Global Protection less visible in urban centers or in remote areas is increasingly challenging. Cluster Coordinator Protection funding has proven to be volatile, mostly because it is not always understood as life- saving. And yet, there is growing consensus of the role protection plays in articulating the purpose of humanitarian response strategies and in helping to prioritize critical interventions during emergencies. -

Understanding Ebola: the 2014 Epidemic Jolie Kaner1,2 and Sarah Schaack2*

Kaner and Schaack Globalization and Health (2016) 12:53 DOI 10.1186/s12992-016-0194-4 REVIEW Open Access Understanding Ebola: the 2014 epidemic Jolie Kaner1,2 and Sarah Schaack2* Abstract Near the end of 2013, an outbreak of Zaire ebolavirus (EBOV) began in Guinea, subsequently spreading to neighboring Liberia and Sierra Leone. As this epidemic grew, important public health questions emerged about how and why this outbreak was so different from previous episodes. This review provides a synthetic synopsis of the 2014–15 outbreak, with the aim of understanding its unprecedented spread. We present a summary of the history of previous epidemics, describe the structure and genetics of the ebolavirus, and review our current understanding of viral vectors and the latest treatment practices. We conclude with an analysis of the public health challenges epidemic responders faced and some of the lessons that could be applied to future outbreaks of Ebola or other viruses. Keywords: Ebola, Ebolavirus, 2014 outbreak, Epidemic, Review Abbreviations: BEBOV, Bundibugyo ebolavirus;CIEBOV,Côte d’Ivoire ebolavirus;EBOV,Ebolavirus; EVD, Ebola virus disease or Ebola; Kb, Kilobase; MSF, Médecins Sans Frontières; REBOV, Reston ebolavirus; SEBOV, Sudan ebolavirus;WHO,World Health Organization; ZEBOV, Zaire ebolavirus Background NP (nucleoprotein), VP35 (polymerase cofactor), VP40 As of April 13th, 2016 there have been 28,652 total cases (matrix protein), GP (glycoprotein), VP30 (transcrip- of Ebola virus disease (EVD; or more generally Ebola) in tion activator), VP24 (secondary matrix protein), and the 2014–2015 West African epidemic [1]. Of these, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase [6]. There are currently 11,325 cases (40 %) were fatal [1]. -

Senior Officials of the United Nations and Officers of Equivalent Rank Whose Duty Station Is New York ______

SENIOR OFFICIALS OF THE UNITED NATIONS AND OFFICERS OF EQUIVALENT RANK WHOSE DUTY STATION IS NEW YORK ___________________________________ HAUTS FONCTIONNAIRES DES NATIONS UNIES ET FONCTIONNAIRES DE RANG ÉQUIVALENT DONT LE LIEU D’AFFECTATION EST NEW YORK _____________________________________ ALTOS FUNCIONARIOS DE LAS NACIONES UNIDAS Y OFICIALES DEL MISMO RANGO CUYO LUGAR DE DESTINO ES NUEVA YORK Last updated: Monday, 28 June 2021 Highlighted items may be pending translation and/or additional details _______________________________________ 1 Table of contents A-Deputy Secretary-General Page 3 B-Under-Secretaries-General and Officers of equivalent rank Page 4 C-Assistant Secretaries-General and Officers of equivalent rank Page 9 D-Under-Secretaries-General and Officers of equivalent rank – Away from Headquarters Page 14 E-Assistant Secretaries-General and Officers of equivalent rank – Away from Headquarters Page 22 2 A. Deputy Secretary-General Vice-Secrétaire générale Vicesecretaria General Name / Nom / Nombre* Title / Titre / Título Extension / Poste / Tel. Interno Room / Bureau / Oficina Ms. Amina J. Mohammed Deputy Secretary-General 3-8010 (Nigeria) Vice-Secrétaire générale S-3847 3-8845 (fax) Vices ecretaria General 3 B. Under-Secretaries-General and Officers of equivalent rank Secrétaires généraux adjoints et fonctionnaires de rang équivalent Secretarios Generales Adjuntos y Oficiales del mismo rango Name / Nom / Nombre* Title / Titre / Título Extension / Poste / Tel. Interno Room / Bureau / Oficina Mr. Movses Abelian Under-Secretary-General for General Assembly and Conference Management (Armenia) Secrétaire général adjoint chargé du Département de l’Assemblée générale et de la gestion 212-963-4151 Mrs. Ruzanna Abelian des conférences S-3065 212-963-8196 (fax) Secretario General Adjunto, Departamento de la Asamblea General y de Gestión de Conferencias Mr. -

Texas Ebola Patient Gets Experimental Drug (Update) 6 October 2014, by Kerry Sheridan

Texas Ebola patient gets experimental drug (Update) 6 October 2014, by Kerry Sheridan A Liberian man diagnosed with Ebola in Texas was fellow heads of state and government around the given an experimental drug for the first time, world to make sure that they are doing everything officials said Monday as the White House mulled that they can to join us in this effort." tougher airport screening at home and abroad. He said the United States is considering tougher Thomas Eric Duncan was given the investigational airport screening to ward against the spread of medication, brincidofovir, on Saturday, the day his cases by airline travelers. condition worsened from serious to critical, said Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas. "We're also going to be working on protocols to do additional passenger screening both at the source The medication is made by the North Carolina- and here in the United States," Obama told based pharmaceutical company Chimerix, and until reporters. now had never been tried in humans with Ebola, the company said. In Nebraska, a US photojournalist who tested positive for Ebola in Liberia arrived at a hospital However, it has been tested in about 1,000 people and was able to walk off the airplane that carried against adenovirus and cytomegalovirus. him. The drug "works by keeping viruses from creating "We are really happy that his symptoms are not additional copies of themselves," Chimerix said. extreme yet," Ashoka Mukpo's mother, Diana, told reporters, adding that he was feverish and Duncan is the first person to be diagnosed with nauseous. Ebola in the United States, and he is believed to have become infected while in Liberia.