The Mali Migration Crisis at a Glance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

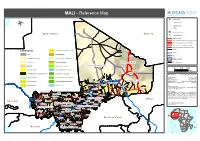

MALI - Reference Map

MALI - Reference Map !^ Capital of State !. Capital of region ® !( Capital of cercle ! Village o International airport M a u r ii t a n ii a A ll g e r ii a p Secondary airport Asphalted road Modern ground road, permanent practicability Vehicle track, permanent practicability Vehicle track, seasonal practicability Improved track, permanent practicability Tracks Landcover Open grassland with sparse shrubs Railway Cities Closed grassland Tesalit River (! Sandy desert and dunes Deciduous shrubland with sparse trees Region boundary Stony desert Deciduous woodland Region of Kidal State Boundary ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Bare rock ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Mosaic Forest / Savanna ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Region of Tombouctou ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 0 100 200 Croplands (>50%) Swamp bushland and grassland !. Kidal Km Croplands with open woody vegetation Mosaic Forest / Croplands Map Doc Name: OCHA_RefMap_Draft_v9_111012 Irrigated croplands Submontane forest (900 -1500 m) Creation Date: 12 October 2011 Updated: -

Côte D'ivoire

CÔTE D’IVOIRE COI Compilation August 2017 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Regional Representation for West Africa - RSD Unit UNHCR Côte d’Ivoire UNHCR Regional Representation for West Africa - RSD Unit UNHCR Côte d’Ivoire Côte d’Ivoire COI Compilation August 2017 This report collates country of origin information (COI) on Côte d’Ivoire up to 15 August 2017 on issues of relevance in refugee status determination for Ivorian nationals. The report is based on publicly available information, studies and commentaries. It is illustrative, but is neither exhaustive of information available in the public domain nor intended to be a general report on human-rights conditions. The report is not conclusive as to the merits of any individual refugee claim. All sources are cited and fully referenced. Users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. UNHCR Regional Representation for West Africa Immeuble FAALO Almadies, Route du King Fahd Palace Dakar, Senegal - BP 3125 Phone: +221 33 867 62 07 Kora.unhcr.org - www.unhcr.org Table of Contents List of Abbreviations .............................................................................................................. 4 1 General Information ....................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Historical background ............................................................................................ -

Eradicating Ebola: Lessons Learned and Medical Advancements Hearing

ERADICATING EBOLA: LESSONS LEARNED AND MEDICAL ADVANCEMENTS HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA, GLOBAL HEALTH, GLOBAL HUMAN RIGHTS, AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JUNE 4, 2019 Serial No. 116–44 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/, http://docs.house.gov, or http://www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 36–558PDF WASHINGTON : 2019 COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York, Chairman BRAD SHERMAN, California MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas, Ranking GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York Member ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia STEVE CHABOT, Ohio THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida JOE WILSON, South Carolina KAREN BASS, California SCOTT PERRY, Pennsylvania WILLIAM KEATING, Massachusetts TED S. YOHO, Florida DAVID CICILLINE, Rhode Island ADAM KINZINGER, Illinois AMI BERA, California LEE ZELDIN, New York JOAQUIN CASTRO, Texas JIM SENSENBRENNER, Wisconsin DINA TITUS, Nevada ANN WAGNER, Missouri ADRIANO ESPAILLAT, New York BRIAN MAST, Florida TED LIEU, California FRANCIS ROONEY, Florida SUSAN WILD, Pennsylvania BRIAN FITZPATRICK, Pennsylvania DEAN PHILLIPS, Minnesota JOHN CURTIS, Utah ILHAN OMAR, Minnesota KEN BUCK, Colorado COLIN ALLRED, Texas RON WRIGHT, Texas ANDY LEVIN, Michigan GUY RESCHENTHALER, Pennsylvania ABIGAIL SPANBERGER, Virginia TIM BURCHETT, Tennessee CHRISSY HOULAHAN, Pennsylvania GREG PENCE, Indiana -

Immeuble CCIA, Avenue Jean Paul II, 01 BP 1387, Abidjan 01 Cote D'ivoire

REQUEST FOR EXPRESSIONS OF INTEREST AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP Immeuble CCIA, Avenue Jean Paul II, 01 BP 1387, Abidjan 01 Cote d’Ivoire Gender, Women and Civil Society Department (AHGC) E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Telephone: +22520264246 Title of the assignment: Consultant-project coordinator to help the Department of Gender, Women and Civil Society (AHGC) in TSF funded project (titled Economic Empowerment of Vulnerable Women in the Sahel Region) in Chad, Mali and Niger. The African Development Bank, with funding from the Transition Support Facility (TSF), hereby invites individual consultants to express their interest for a consultancy to support the Multinational project Economic Empowerment of Vulnerable Women in three transition countries specifically Chad, Mali and Niger Brief description of the Assignment: The consultant-project coordinator will support the effective operationalization of the project that includes: (i) Developing the project’s annual work Plan and budget and coordinating its implementation; (ii) Preparing reports or minutes for various activities of the project at each stage of each consultancy in accordance with the Bank reporting guideline; (iii) Contributing to gender related knowledge products on G5 Sahel countries (including country gender profiles, country policy briefs, etc.) that lead to policy dialogue with a particular emphasis on fragile environments. Department issuing the request: Gender, Women and Civil Society Department (AHGC) Place of assignment: Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire Duration of the assignment: 12 months Tentative Date of commencement: 5th September 2020 Deadline for Applications: Wednesday 26th August 2020 at 17h30 GMT Applications to be submitted to: [email protected]; [email protected] ; [email protected] For the attention of: Ms. -

Of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO

Assessing the of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO REPORT 3/2019 Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2019 ISBN: 978-82-7002-346-2 Any views expressed in this publication are those of the author. Tey should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. Te text may not be re-published in part or in full without the permission of NUPI and the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: effectivepeaceops.net | www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 99 40 50 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 Assessing the Efectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC (MONUC-MONUSCO) Lead Author Dr Alexandra Novosseloff, International Peace Institute (IPI), New York and Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo Co-authors Dr Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Prof. Tomas Mandrup, Stellenbosch University, South Africa, and Royal Danish Defence College, Copenhagen Aaron Pangburn, Social Science Research Council (SSRC), New York Data Contributors Ryan Rappa and Paul von Chamier, Center on International Cooperation (CIC), New York University, New York EPON Series Editor Dr Cedric de Coning, NUPI External Reference Group Dr Tatiana Carayannis, SSRC, New York Lisa Sharland, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra Dr Charles Hunt, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, Australia Adam Day, Centre for Policy Research, UN University, New York Cover photo: UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti UN Photo/ Abel Kavanagh Contents Acknowledgements 5 Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 13 Te effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC across eight critical dimensions 14 Strategic and Operational Impact of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Constraints and Challenges of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Current Dilemmas 19 Introduction 21 Section 1. -

History, External Influence and Political Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies Economics Department 2014 History, External Influence and oliticalP Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR) Henry Kam Kah University of Buea, Cameroon Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jade Part of the Econometrics Commons, Growth and Development Commons, International Economics Commons, Political Economy Commons, Public Economics Commons, and the Regional Economics Commons Kam Kah, Henry, "History, External Influence and oliticalP Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR)" (2014). Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies. 5. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jade/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Economics Department at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies 2014 Volume 3 Issue 1 ISSN:2161-8216 History, External Influence and Political Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR) Henry Kam Kah University of Buea, Cameroon ABSTRACT This paper examines the complex involvement of neighbors and other states in the leadership or political crisis in the CAR through a content analysis. It further discusses the repercussions of this on the unity and leadership of the country. The CAR has, for a long time, been embroiled in a crisis that has impeded the unity of the country. It is a failed state in Africa to say the least, and the involvement of neighboring and other states in the crisis in one way or the other has compounded the multifarious problems of this country. -

Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel

Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel Towards Peaceful Coexistence UNOWAS STUDY 1 2 Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel Towards Peaceful Coexistence UNOWAS STUDY August 2018 3 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations p.8 Chapter 3: THE REPUBLIC OF MALI p.39-48 Acknowledgements p.9 Introduction Foreword p.10 a. Pastoralism and transhumance UNOWAS Mandate p.11 Pastoral Transhumance Methodology and Unit of Analysis of the b. Challenges facing pastoralists Study p.11 A weak state with institutional constraints Executive Summary p.12 Reduced access to pasture and water Introductionp.19 c. Security challenges and the causes and Pastoralism and Transhumance p.21 drivers of conflict Rebellion, terrorism, and the Malian state Chapter 1: BURKINA FASO p.23-30 Communal violence and farmer-herder Introduction conflicts a. Pastoralism, transhumance and d. Conflict prevention and resolution migration Recommendations b. Challenges facing pastoralists Loss of pasture land and blockage of Chapter 4: THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF transhumance routes MAURITANIA p.49-57 Political (under-)representation and Introduction passivity a. Pastoralism and transhumance in Climate change and adaptation Mauritania Veterinary services b. Challenges facing pastoralists Education Water scarcity c. Security challenges and the causes and Shortages of pasture and animal feed in the drivers of conflict dry season Farmer-herder relations Challenges relating to cross-border Cattle rustling transhumance: The spread of terrorism to Burkina Faso Mauritania-Mali d. Conflict prevention and resolution Pastoralists and forest guards in Mali Recommendations Mauritania-Senegal c. Security challenges and the causes and Chapter 2: THE REPUBLIC OF GUINEA p.31- drivers of conflict 38 The terrorist threat Introduction Armed robbery a. -

Appraisal Report Kankan-Kouremale-Bamako Road Multinational Guinea-Mali

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND ZZZ/PTTR/2000/01 Language: English Original: French APPRAISAL REPORT KANKAN-KOUREMALE-BAMAKO ROAD MULTINATIONAL GUINEA-MALI COUNTRY DEPARTMENT OCDW WEST REGION JANUARY 1999 SCCD : N.G. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PROJECT INFORMATION BRIEF, EQUIVALENTS, ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS, LIST OF ANNEXES AND TABLES, BASIC DATA, PROJECT LOGICAL FRAMEWORK, ANALYTICAL SUMMARY i-ix 1 INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Genesis and Background.................................................................................... 1 1.2 Performance of Similar Projects..................................................................................... 2 2 THE TRANSPORT SECTOR ........................................................................................... 3 2.1 The Transport Sector in the Two Countries ................................................................... 3 2.2 Transport Policy, Planning and Coordination ................................................................ 4 2.3 Transport Sector Constraints.......................................................................................... 4 3 THE ROAD SUB-SECTOR .............................................................................................. 5 3.1 The Road Network ......................................................................................................... 5 3.2 The Automobile Fleet and Traffic................................................................................. -

Building Resilience in Africa's Drylands

REGIONAL INITIATIVE FOR AFRICA Building resilience in Africa’s drylands FOCUS COUNTRIES Burkina Faso, Chad, Ethiopia, Kenya, Madagascar, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Somalia, South Sudan, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. OVERALL GOAL Enhance the capacity of dryland countries to anticipate, mitigate and respond to shocks, threats and crises affecting their livelihoods. ABOUT THE REGIONAL INITIATIVE Populations in Africa are increasingly exposed to the negative impact of natural and human-induced disasters such as drought, floods, disease epidemics and conflicts which threaten the agriculture production systems and livelihoods of vulnerable communities. The initiative on “Building Resilience in Africa’s Drylands” was developed to enhance the capacity of these communities to withstand and bounce back from these crises. It aims to strengthen institutional capacity for resilience; support early warning and information management systems; build community level resilience; and respond to emergencies and crises. ZIMBABWE Vegetable farming in Chirumhanzi district. ©FAO/Believe Nyakudjara ZIMBABWE Emergency drought mitigation for livestock in Matabeleland province. ©FAO/Believe Nyakudjara practices and knowledge in the region. The Regional MAKING A DIFFERENCE Initiative also seeks to support countries in meeting one of the key commitments of the Malabo Declaration on The Regional initiative strengthens institutional capacity reducing the number of people in Africa vulnerable to for resilience; supports early warning and information climate change and other threats. management systems; builds community level resilience; and responds to emergencies and crises. Priority actions include: IN PRACTICE > Provide support in areas of resilience policy development and implementation, resilience To achieve resilience in Africa’s drylands in the focus measurement, vulnerability analysis, and strategy countries, the initiative is focusing its efforts on: development and implementation. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE Symbol: "NAC" Toronto Stock Exchange North Atlantic acquires the Kourouba gold project in Mali Toronto, Canada, February 5, 2007: North Atlantic Resources Ltd. (“the Company”) reports: North Atlantic Resources is pleased to announce that it has acquired an option on the 185 square kilometer Kourouba gold exploration permit in southern Mali. The Kourouba project is located in the Koulikoro Region, 150 kilometers southeast of the capital, Bamako. The property covers a strike length of 14 kilometers of prospective stratigraphy in the Birimian Yanfolila greenstone belt. Under the terms of an option agreement, the Company can acquire the Kourouba exploration permit by paying an initial payment of US$60,000, US$100,000 on the first anniversary, US$140,000 on the second anniversary, and US$200,000 on the third anniversary, for a total of US$500,000. The property is subject to a 2.5% Net Smelter Returns Royalty which can be purchased any time by the Company for US$5.5 million. In the central part of the property, a previously-completed soil sampling program, at a density of 500 meters by 200 meters, defined a north-trending, continuous, gold in soil anomaly, with samples containing at least 100 parts per billion gold over a nominal strike length of 2,500 meters and a peak value of 1,420 parts per billion (1.42 grams per tonne gold). Follow-up soil sampling, completed by the vendor of the property, confirmed the presence of gold in termite mound samples, indicating that the gold in soil anomaly is probably coincident with gold in saprolite and bedrock below the anomaly. -

Mali – Beyond Cotton, Searching for “Green Gold”* Yoshiko Matsumoto-Izadifar

Mali – Beyond Cotton, Searching for “Green Gold”* Yoshiko Matsumoto-Izadifar Mali is striving for agricultural diversification to lessen its high dependence on cotton and gold. The Office du Niger zone has great potential for agricultural diversification, in particular for increasing rice and horticultural production. Tripartite efforts by private agribusiness, the Malian government and the international aid community are the key to success. Mali’s economy faces the challenge of Office du Niger Zone: Growing Potential for agricultural diversification, as it needs to lessen Agricultural Diversification its excessive dependence on cotton and gold. Livestock, cotton and gold are currently the In contrast to the reduced production of cotton, country’s main sources of export earnings (5, 25 cereals showed good progress in 2007. A and 63 per cent respectively in 2005). However, substantial increase in rice production (up more a decline in cotton and gold production in 2007 than 40 per cent between 2002 and 2007) shows slowed the country’s economic growth. Mali has the potential to overcome its dependence on cotton (FAO, 2008). The Recent estimates suggest that the country’s gold government hopes to make the zone a rice resources will be exhausted in ten years (CCE, granary of West Africa. 2007), and “white gold”, as cotton is known, is in a difficult state owing to stagnant productivity The Office du Niger zone (see Figure 1), one of and low international market prices, even the oldest and largest irrigation schemes in sub- though the international price of cotton Saharan Africa, covers 80 per cent of Mali’s increased slightly in 2007 (AfDB/OECD, 2008). -

9781464804335.Pdf

Land Delivery Systems in West African Cities Land Delivery Systems in West African Cities The Example of Bamako, Mali Alain Durand-Lasserve, Maÿlis Durand-Lasserve, and Harris Selod A copublication of the Agence Française de Développement and the World Bank © 2015 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / Th e World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 18 17 16 15 Th is work is a product of the staff of Th e World Bank with external contributions. Th e fi ndings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily refl ect the views of Th e World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent, or the Agence Française de Développement. Th e World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. Th e boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of Th e World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of Th e World Bank, all of which are specifi cally reserved. Rights and Permissions Th is work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: Durand-Lasserve, Alain, Maÿlis Durand-Lasserve, and Harris Selod.