Addressing Root Causes of Conflict: a Case Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNICEF DRC Evaluation Report 2007-2011 Programme for The

ICC-01/04-01/06-3344-Anx23-tENG 12-12-2017 1/88 EK T UNICEF DRC Evaluation Report 2007-2011 Programme for the Reintegration of Children Associated with Armed Forces and Armed Groups in the DRC Sylvie Bodineau May-June 2011 Official Court Translation ICC-01/04-01/06-3344-Anx23-tENG 12-12-2017 2/88 EK T Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Methodology ....................................................................................................................................... 6 1- What has been done................................................................................................................ 10 1.1 Different types of intervention depending on the geopolitical context, the CPAs present and the availability of funding.................................................................................................................. 10 1.2 UNICEF’s role............................................................................................................................ 14 1.3 Situation in June 2011............................................................................................................. -

Ituri:Stakes, Actors, Dynamics

ITURI STAKES, ACTORS, DYNAMICS FEWER/AIP/APFO/CSVR would like to stress that this report is based on the situation observed and information collected between March and August 2003, mainly in Ituri and Kinshasa. The 'current' situation therefore refers to the circumstances that prevailed as of August 2003, when the mission last visited the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the Swedish International Development Agency. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Swedish Government and its agencies. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the Department for Development Policy, Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Finnish Government and its agencies. Copyright 2003 © Africa Initiative Program (AIP) Africa Peace Forum (APFO) Centre for Study of Violence and Reconciliation (CSVR) Forum on Early Warning and Early Response (FEWER) The views expressed by participants in the workshop are not necessarily those held by the workshop organisers and can in no way be take to reflect the views of AIP, APFO, CSVR and FEWER as organisations. 2 List of Acronyms............................................................................................................................... 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...................................................................................................................................... -

U.N. Peacekeeping Operations in Africa

U.N. Peacekeeping Operations in Africa September 23, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45930 SUMMARY R45930 U.N. Peacekeeping Operations in Africa September 23, 2019 Many Members of Congress have demonstrated an interest in the mandates, effectiveness, and funding status of United Nations (U.N.) peacekeeping operations in Africa as an integral Luisa Blanchfield component of U.S. policy toward Africa and a key tool for fostering greater stability and security Specialist in International on the continent. As of September 2019, there are seven U.N. peacekeeping operations in Africa: Relations the U.N. Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Alexis Arieff Republic (MINUSCA), Specialist in African Affairs the U.N. Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), the U.N. Interim Security Force for Abyei (UNISFA), Lauren Ploch Blanchard Specialist in African Affairs the U.N. Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS), the U.N. Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO), the African Union-United Nations Mission in Darfur (UNAMID), and the U.N. Mission for the Organization of a Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO). The United States, as a permanent member of the U.N. Security Council, plays a key role in establishing, renewing, and funding U.N. peacekeeping operations, including those in Africa. For 2019, the U.N. General Assembly assessed the U.S. share of U.N. peacekeeping operation budgets at 27.89%; since the mid-1990s Congress has capped the U.S. payment at 25% due to concerns that the current assessment is too high. During the Trump Administration, the United States generally has voted in the Security Council for the renewal and funding of existing U.N. -

Of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO

Assessing the of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO REPORT 3/2019 Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2019 ISBN: 978-82-7002-346-2 Any views expressed in this publication are those of the author. Tey should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. Te text may not be re-published in part or in full without the permission of NUPI and the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: effectivepeaceops.net | www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 99 40 50 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 Assessing the Efectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC (MONUC-MONUSCO) Lead Author Dr Alexandra Novosseloff, International Peace Institute (IPI), New York and Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo Co-authors Dr Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Prof. Tomas Mandrup, Stellenbosch University, South Africa, and Royal Danish Defence College, Copenhagen Aaron Pangburn, Social Science Research Council (SSRC), New York Data Contributors Ryan Rappa and Paul von Chamier, Center on International Cooperation (CIC), New York University, New York EPON Series Editor Dr Cedric de Coning, NUPI External Reference Group Dr Tatiana Carayannis, SSRC, New York Lisa Sharland, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra Dr Charles Hunt, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, Australia Adam Day, Centre for Policy Research, UN University, New York Cover photo: UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti UN Photo/ Abel Kavanagh Contents Acknowledgements 5 Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 13 Te effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC across eight critical dimensions 14 Strategic and Operational Impact of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Constraints and Challenges of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Current Dilemmas 19 Introduction 21 Section 1. -

Reconciling the Protection of Civilians and Host-State Support in UN Peacekeeping

MAY 2020 With or Against the State? Reconciling the Protection of Civilians and Host-State Support in UN Peacekeeping PATRYK I. LABUDA Cover Photo: Elements of the UN ABOUT THE AUTHOR Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s PATRYK I. LABUDA is a Postdoctoral Scholar at the (MONUSCO) Force Intervention Brigade Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy and a Non-resident and the Congolese armed forces Fellow at the International Peace Institute. The author’s undertake a joint operation near research is supported by the Swiss National Science Kamango, in eastern Democratic Foundation. Republic of the Congo, March 20, 2014. UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Disclaimer: The views expressed in this paper represent those of the author The author wishes to thank all the UN officials, member- and not necessarily those of the state representatives, and civil society representatives International Peace Institute. IPI welcomes consideration of a wide interviewed for this report. He thanks MONUSCO in parti - range of perspectives in the pursuit of cular for organizing a workshop in Goma, which allowed a well-informed debate on critical him to gather insights from a range of stakeholders.. policies and issues in international Special thanks to Oanh-Mai Chung, Koffi Wogomebou, Lili affairs. Birnbaum, Chris Johnson, Sigurður Á. Sigurbjörnsson, Paul Egunsola, and Martin Muigai for their essential support in IPI Publications organizing the author’s visits to the Central African Adam Lupel, Vice President Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Albert Trithart, Editor South Sudan. The author is indebted to Namie Di Razza for Meredith Harris, Editorial Intern her wise counsel and feedback on various drafts through - out this project. -

A Life of Fear and Flight

A LIFE OF FEAR AND FLIGHT The Legacy of LRA Brutality in North-East Democratic Republic of the Congo We fled Gilima in 2009, as the LRA started attacking there. From there we fled to Bangadi, but we were confronted with the same problem, as the LRA was attacking us. We fled from there to Niangara. Because of insecurity we fled to Baga. In an attack there, two of my children were killed, and one was kidnapped. He is still gone. Two family members of my husband were killed. We then fled to Dungu, where we arrived in July 2010. On the way, we were abused too much by the soldiers. We were abused because the child of my brother does not understand Lingala, only Bazande. They were therefore claiming we were LRA spies! We had to pay too much for this. We lost most of our possessions. Once in Dungu, we were first sleeping under a tree. Then someone offered his hut. It was too small with all the kids, we slept with twelve in one hut. We then got another offer, to sleep in a house at a church. The house was, however, collapsing and the owner chased us. He did not want us there. We then heard that some displaced had started a camp, and that we could get a plot there. When we had settled there, it turned out we had settled outside of the borders of the camp, and we were forced to leave. All the time, we could not dig and we had no access to food. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #2

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO - COMPLEX EMERGENCY FACT SHEET #2, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2018 MARCH 9, 2018 NUMBERS AT USAID/OFDA1 FUNDING HIGHLIGHTS BY SECTOR IN FY 2017–2018 A GLANCE • Conflict continues to displace 3% 3% populations within DRC and to 6% neighboring countries 6% 13.1 34% • requestsUN nearly $1.7 billion to meet 7% humanitarian needs in DRC during million 2018 People in DRC Requiring 18% • Cholera and polio type 2 remain critical Humanitarian Assistance 23% in 2018 health concerns UN – December 2017 Logistics Support & Relief Commodities (34%) Health (23%) HUMANITARIAN FUNDING Water, Sanitation & Hygiene (18%) FOR THE DRC RESPONSE IN FY 2017–2018 Protection (7%) Humanitarian Coordination & Information Management (6%) 7.7 Agriculture & Food Security (6%) USAID/OFDA $52,686,506 Nutrition (3%) million Other (3%) USAID/FFP $77,115,857 Acutely Food-Insecure 2 3 People in DRC USAID/FFP FUNDING State/PRM $62,496,034 UN – August 2017 BY MODALITY IN FY 2017–2018 48% 39% 11% 2% Local & Regional Procurement (48%) $192,298,397 U.S. In-Kind Food Aid (39%) 4.5 Cash Transfers for Food (11%) Complementary Services (2%) million IDPs in DRC UN – December 2017 KEY DEVELOPMENTS • The 2018 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) requests nearly $1.7 billion to provide humanitarian assistance to 10.5 million of the estimated 13.1 million people in need in 684,000 Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The 2018 appeal is the largest to date for DRC and reflects the widening scope of emergency needs in the country. DRC Refugees and Asylum-Seekers Across • Conflict continues to drive population displacement in DRC, with the UN projecting up Africa to 2.4 million new internally displaced persons (IDPs) by the end of 2018. -

Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks and Other Emergencies

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 28: 05 - 11 July 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 11 July 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 1 117 106 12 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 146 082 3 836 Algeria ¤ 1 034 0 6 328 185 Mauritania 1 313 74 14 463 528 48 0 110 0 46 175 1 194 Niger 21 672 489 6 284 29 Mali 21 0 9 0 Cape Verde 6 471 16 4 954 174 Chad Eritrea Senegal 5 538 194 Gambia 66 0 33 006 289 1 414 8 Guinea-Bissau 847 17 Burkina Faso 2 060 56 277 071 4 343 168 552 2 124 Guinea 13 509 168 13 0 3 947 70 2 2 Benin 198 0 Nigeria 1 286 4 61 0 30 0 Ethiopia 13 2 6 995 50 556 5 872 15 Sierra Leone Togo 626 0 80 858 1 324 Ghana 7 142 98 Côte d'Ivoire 10 879 117 19 000 304 81 0 45 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 1 313 2 0 25 0 50 14 0 97 585 801 6 738 221 Cameroon 24 117 299 3 0 48 776 318 35 339 197 7 0 58 0 199 2 1 411 30 9 1 620 1 188 754 3 722 2 0 168 0 1 1 6 031 112 14 270 133 8 790 122 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 867 2 827 9 Sao Tome and Principe 4 0 5 215 144 716 494 198 87 277 2 104 Kenya Gabon Legend Congo 3 516 93 305 26 Rwanda 8 199 104 2 392 37 48 244 560 25 164 162 Democratic Republic of the Congo 12 790 167 Burundi Measles Humanitarian crisis 5 686 8 Seychelles 44 139 980 436 0 693 57 Monkeypox Yellow fever United Republic of Tanzania 197 0 16 957 68 Meningitis Lassa fever 509 21 241 1 6 257 229 Leishmaniasis Cholera 39 958 935 175 729 2 822 Comoros Plague 304 3 cVDPV2 Angola Malawi Diarrhoeal disease in children under five years 36 926 1 250 -

Democratic Republic of Congo

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 11 (A) - July 2003 I hid in the mountains and went back down to Songolo at about 3:00 p.m. I saw many people killed and even saw traces of blood where people had been dragged. I counted 82 bodies most of whom had been killed by bullets. We did a survey and found that 787 people were missing – we presumed they were all dead though we don’t know. Some of the bodies were in the road, others in the forest. Three people were even killed by mines. Those who attacked knew the town and posted themselves on the footpaths to kill people as they were fleeing. -- Testimony to Human Rights Watch ITURI: “COVERED IN BLOOD” Ethnically Targeted Violence In Northeastern DR Congo 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] “You cannot escape from the horror” This story of fifteen-year-old Elise is one of many in Ituri. She fled one attack after another and witnessed appalling atrocities. Walking for more than 300 miles in her search for safety, Elise survived to tell her tale; many others have not. -

MONUSCO, 20 Years in Democratic Republic of Congo. What

MONUSCO, 20 Years in Democratic Republic of Congo. What Are the Priorities For Its New Mandate? Analysis December 2019 / N° 746a Cover picture: The gates to the MONUSCO headquarters in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), 19 February 2015. © Michael Kappeler / DPA/DPA Picture Alliance TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS 5 MAP OF MONUSCO’S PRESENCE IN DRC 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 METHODOLOGY 9 INTRODUCTION 10 I. OVERVIEW OF THE POLITICAL, SECURITY AND HUMAN RIGHTS CONTEXT IN DRC 12 A. An uncertain context of emergence from political crisis and lifting of restrictions on democratic space 12 B. A worrying security context, marked by continuing violations of human rights and inter-communal tensions and conflicts throughout the country 14 II. OVERVIEW OF THE CONTEXT OF RENEWAL OF MONUSCO’S MANDATE 18 A. A nine-month interim mandate 18 B. Towards MONUSCO’s reconfiguration 19 III. PRIORITIES FOR THE NEW MONUSCO MANDATE ACCORDING TO FIDH AND ITS MEMBER ORGANISATIONS IN DRC 21 A. On democratic space and governance 21 1. Consolidate efforts already undertaken to open up democratic space 21 2. Encourage institutional reforms 22 B. On security and civilian protection 24 1. Prioritise a non-military community-based and local approach to civilian protection 24 2. Strengthen civil and military coordination 25 3. Provide a rapid response to protection needs 26 4. Adopt a regional approach to civilian protection 26 5. Pursue efforts to reform the UN peacekeeping system 26 C. On justice and the fight against impunity 27 1. Fight impunity for the most serious crimes 27 2. Build the capacities of the judicial system to increase its efficiency and independence 29 3. -

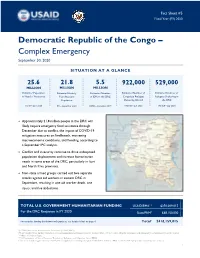

DRC Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #5 09.30.2020

Fact Sheet #5 Fiscal Year (FY) 2020 Democratic Republic of the Congo – Complex Emergency September 30, 2020 SITUATION AT A GLANCE 25.6 21.8 5.5 922,000 529,000 MILLION MILLION MILLION Estimated Population Estimated Acutely Estimated Number Estimated Number of Estimated Number of in Need of Assistance Congolese Refugees Refugees Sheltering in Food Insecure of IDPs in the DRC Population Sheltering Abroad the DRC OCHA – June 2020 UNHCR – July 2020 UNHCR – July 2020 IPC – September 2020 OCHA – December 2019 Approximately 21.8 million people in the DRC will likely require emergency food assistance through December due to conflict, the impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures on livelihoods, worsening macroeconomic conditions, and flooding, according to a September IPC analysis. Conflict and insecurity continue to drive widespread population displacement and increase humanitarian needs in some areas of the DRC, particularly in Ituri and North Kivu provinces. Non-state armed groups carried out two separate attacks against aid workers in eastern DRC in September, resulting in one aid worker death, one injury, and five abductions. TOTAL U.S. GOVERNMENT HUMANITARIAN FUNDING USAID/BHA1,2 $350,009,015 For the DRC Response in FY 2020 State/PRM3 $68,150,000 For complete funding breakdown with partners, see detailed chart on page 6 Total4 $418,159,015 1USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA) 2 Total USAID/BHA funding includes non-food humanitarian assistance from the former Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance and emergency food assistance from the former Office of Food for Peace. 3 U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (State/PRM) 4 This total includes approximately $23,833,699 in supplemental funding through USAID/BHA and State/PRM for COVID-19 preparedness and response activities. -

Intersectionality and International Law: Recognizing Complex Identities on the Global Stage

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLH\28-1\HLH105.txt unknown Seq: 1 6-JUL-15 11:18 Intersectionality and International Law: Recognizing Complex Identities on the Global Stage Aisha Nicole Davis* As a legal theory, intersectionality seeks to create frameworks that con- sider the multiple identities that individuals possess, including race, gen- der, sexuality, age, and ability. When applied, intersectionality recognizes complexities in an individual’s identity to an extent not possi- ble using mechanisms that focus solely on one minority marker. This Note proposes incorporating intersectional consideration in the realm of inter- national human rights law and international humanitarian law to bet- ter address the human rights violations that affect women whose identities fall within more than one minority group because of their ethnicity or race. The Note begins with an explanation of intersectional- ity, and then applies intersectionality to human rights mechanisms within the United Nations and to cases in international criminal tribu- nals and the International Criminal Court. As it stands, international human rights law, international criminal law, and international hu- manitarian law view women who are members of a racial or ethnic mi- nority as variants on a given category. This Note contends that by applying a framework that further incorporates intersectionality—that is, both in discourse and action—in international human rights law, international humanitarian law, and international criminal law, these women’s identities will be more fully recognized, opening up the possibil- ity for more representative women’s rights discourse, and remedies for human rights abuses that better address the scope and nature of the violations.