A Life of Fear and Flight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

With Effect from 1 April 2012 Through 30 June 2012

List of locations where payment of danger pay has been approved' with effect from 1 April 2012 through 30 June 2012: AFGHANISTAN CONGO, DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF - North Kivu Province, South Kivu Province, Orientale Province - (only Bas Uele, Haut Uele and Ituri Districts), Maniema Province ETHIOPIA - Somali Region IRAQ - Entire country except Erbil KENYA - North Eastern Province (Garissa, Dadaab, Mandera, Wajir, Ijara) LEBANON - South Lebanon (UNIFIL Area of Operations, except the Tyre pocket) PAKISTAN - Balochistan Province, Khyber Pakhtunkhawa Province (formerly, North-West Frontier Province) and Federally Administrated Tribal Areas SOMALIA SOUTH SUDAN - Unity State, Upper Nile State, Jonglei State, Warrap State (except Tonji South county), in Lakes State (only Awerial, Yirol East, Rumbek Centre, Rumbek North and Rumbek East counties), in Northern Bar El Gazal State (only Aweil East and Aweil North counties), in Western Bar El Gazal State (all locations north of the road Kafia-Gabir-Kosho-Raja, excluding Raga town), Western Equatoria (only all locations south of the road Morobo-Yei-Maridi- Yambio-Nadi-Tambura, except Yambio town) SUDAN - the Darfurs (West, South and North Darfur), Abyei Administered Area, South Kordofan State and Blue Nile State SYRIA ARAB REPUBLIC - Entire country except Damascus (city boundaries) and UNDOF Area of Operations • YEMEN Addendum Please note that in addition to the approved locations above, on 3 July 2012, Danger Pay was also approved for the location below with retroactive effective date of 1 to 30 June 2012: ® Damascus, Syria. -

Addressing Root Causes of Conflict: a Case Study Of

Experience paper Addressing root causes of conflict: A case study of the International Security and Stabilization Support Strategy and the Patriotic Resistance Front of Ituri (FRPI) in Ituri Province, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo Oslo, May 2019 1 About the Author: Ingebjørg Finnbakk has been deployed by the Norwegian Resource Bank for Democracy and Human Rights (NORDEM) to the Stabilization Support Unit (SSU) in MONUSCO from August 2016 until February 2019. Together with SSU Headquarters and Congolese partners she has been a key actor in developing and implementing the ISSSS program in Ituri Province, leading to a joint MONUSCO and Government process and strategy aimed at demobilizing a 20-year-old armed group in Ituri, the Patriotic Resistance Front of Ituri (FRPI). The views expressed in this report are her own, and do not represent those of either the UN or the Norwegian Refugee Council/NORDEM. About NORDEM: The Norwegian Resource Bank for Democracy and Human Rights (NORDEM) is NORCAP’s civilian capacity provider specializing in human rights and support for democracy. NORDEM has supported the SSU with personnel since 2013, hence contribution significantly with staff through the various preparatory phases as well as during the implementation. Acknowledgements: Reaching the point of implementing ISSSS phase two programs has required a lot of analyses, planning and stakeholder engagement. The work presented in this report would not be possible without all the efforts of previous SSU staff under the leadership of Richard de La Falaise. The FRPI process would not have been possible without the support and visions from Francois van Lierde (deployed by NORDEM) and Frances Charles at SSU HQ level. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #2

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO - COMPLEX EMERGENCY FACT SHEET #2, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2018 MARCH 9, 2018 NUMBERS AT USAID/OFDA1 FUNDING HIGHLIGHTS BY SECTOR IN FY 2017–2018 A GLANCE • Conflict continues to displace 3% 3% populations within DRC and to 6% neighboring countries 6% 13.1 34% • requestsUN nearly $1.7 billion to meet 7% humanitarian needs in DRC during million 2018 People in DRC Requiring 18% • Cholera and polio type 2 remain critical Humanitarian Assistance 23% in 2018 health concerns UN – December 2017 Logistics Support & Relief Commodities (34%) Health (23%) HUMANITARIAN FUNDING Water, Sanitation & Hygiene (18%) FOR THE DRC RESPONSE IN FY 2017–2018 Protection (7%) Humanitarian Coordination & Information Management (6%) 7.7 Agriculture & Food Security (6%) USAID/OFDA $52,686,506 Nutrition (3%) million Other (3%) USAID/FFP $77,115,857 Acutely Food-Insecure 2 3 People in DRC USAID/FFP FUNDING State/PRM $62,496,034 UN – August 2017 BY MODALITY IN FY 2017–2018 48% 39% 11% 2% Local & Regional Procurement (48%) $192,298,397 U.S. In-Kind Food Aid (39%) 4.5 Cash Transfers for Food (11%) Complementary Services (2%) million IDPs in DRC UN – December 2017 KEY DEVELOPMENTS • The 2018 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) requests nearly $1.7 billion to provide humanitarian assistance to 10.5 million of the estimated 13.1 million people in need in 684,000 Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The 2018 appeal is the largest to date for DRC and reflects the widening scope of emergency needs in the country. DRC Refugees and Asylum-Seekers Across • Conflict continues to drive population displacement in DRC, with the UN projecting up Africa to 2.4 million new internally displaced persons (IDPs) by the end of 2018. -

Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks and Other Emergencies

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 28: 05 - 11 July 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 11 July 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 1 117 106 12 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 146 082 3 836 Algeria ¤ 1 034 0 6 328 185 Mauritania 1 313 74 14 463 528 48 0 110 0 46 175 1 194 Niger 21 672 489 6 284 29 Mali 21 0 9 0 Cape Verde 6 471 16 4 954 174 Chad Eritrea Senegal 5 538 194 Gambia 66 0 33 006 289 1 414 8 Guinea-Bissau 847 17 Burkina Faso 2 060 56 277 071 4 343 168 552 2 124 Guinea 13 509 168 13 0 3 947 70 2 2 Benin 198 0 Nigeria 1 286 4 61 0 30 0 Ethiopia 13 2 6 995 50 556 5 872 15 Sierra Leone Togo 626 0 80 858 1 324 Ghana 7 142 98 Côte d'Ivoire 10 879 117 19 000 304 81 0 45 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 1 313 2 0 25 0 50 14 0 97 585 801 6 738 221 Cameroon 24 117 299 3 0 48 776 318 35 339 197 7 0 58 0 199 2 1 411 30 9 1 620 1 188 754 3 722 2 0 168 0 1 1 6 031 112 14 270 133 8 790 122 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 867 2 827 9 Sao Tome and Principe 4 0 5 215 144 716 494 198 87 277 2 104 Kenya Gabon Legend Congo 3 516 93 305 26 Rwanda 8 199 104 2 392 37 48 244 560 25 164 162 Democratic Republic of the Congo 12 790 167 Burundi Measles Humanitarian crisis 5 686 8 Seychelles 44 139 980 436 0 693 57 Monkeypox Yellow fever United Republic of Tanzania 197 0 16 957 68 Meningitis Lassa fever 509 21 241 1 6 257 229 Leishmaniasis Cholera 39 958 935 175 729 2 822 Comoros Plague 304 3 cVDPV2 Angola Malawi Diarrhoeal disease in children under five years 36 926 1 250 -

Drc): Case Studies from Katanga, Ituri and Kivu

CONFLICT BETWEEN INDUSTRIAL AND ARTISANAL MINING IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO (DRC): CASE STUDIES FROM KATANGA, ITURI AND KIVU Ruben de Koning Introduction The mining sector in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is widely regarded as the key engine for post-conflict reconstruction. To attract for- eign investment, the government in 2002 enacted a new mining code that makes it easier for foreign companies to obtain industrial mining titles. Within a few years exploration concessions covered about a third of the country. Meanwhile, exploitation rights to the most important proven deposits were converted to new joint-ventures between foreign investors and Congolese state mining companies. The rapid attribution of min- ing titles has, however, not lead to a resumption of industrial mining on the scale the central government and its foreign donors had hoped for. Apart from a few copper and cobalt mines in the southern Katanga prov- ince, mineral production in the rest of the country, but also in Katanga, remains largely artisanal. Artisanal mining employs up to two million people across the country and largely takes place on concessions where industrial mining is supposed happen (Wold Bank 2009). In many of these artisanal mining areas and particularly in the eastern DRC state functions have almost completely eroded during two consecutive civil wars. Arti- sanal miners often work in dangerous conditions and are forced to pay numerous illegal taxes or to work for the military and rebel forces that control mines. At the same time, the local power complexes that emerged around artisanal mining operations have withheld large scale industrial investment, thereby preventing displacement of artisanal miners from concessions. -

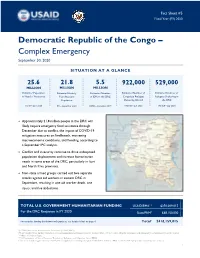

DRC Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #5 09.30.2020

Fact Sheet #5 Fiscal Year (FY) 2020 Democratic Republic of the Congo – Complex Emergency September 30, 2020 SITUATION AT A GLANCE 25.6 21.8 5.5 922,000 529,000 MILLION MILLION MILLION Estimated Population Estimated Acutely Estimated Number Estimated Number of Estimated Number of in Need of Assistance Congolese Refugees Refugees Sheltering in Food Insecure of IDPs in the DRC Population Sheltering Abroad the DRC OCHA – June 2020 UNHCR – July 2020 UNHCR – July 2020 IPC – September 2020 OCHA – December 2019 Approximately 21.8 million people in the DRC will likely require emergency food assistance through December due to conflict, the impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures on livelihoods, worsening macroeconomic conditions, and flooding, according to a September IPC analysis. Conflict and insecurity continue to drive widespread population displacement and increase humanitarian needs in some areas of the DRC, particularly in Ituri and North Kivu provinces. Non-state armed groups carried out two separate attacks against aid workers in eastern DRC in September, resulting in one aid worker death, one injury, and five abductions. TOTAL U.S. GOVERNMENT HUMANITARIAN FUNDING USAID/BHA1,2 $350,009,015 For the DRC Response in FY 2020 State/PRM3 $68,150,000 For complete funding breakdown with partners, see detailed chart on page 6 Total4 $418,159,015 1USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA) 2 Total USAID/BHA funding includes non-food humanitarian assistance from the former Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance and emergency food assistance from the former Office of Food for Peace. 3 U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (State/PRM) 4 This total includes approximately $23,833,699 in supplemental funding through USAID/BHA and State/PRM for COVID-19 preparedness and response activities. -

Review of the National Program for Onchocerciasis Control in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease Review Review of the National Program for Onchocerciasis Control in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Jean-Claude Makenga Bof 1,* , Fortunat Ntumba Tshitoka 2, Daniel Muteba 2, Paul Mansiangi 3 and Yves Coppieters 1 1 Ecole de Santé Publique, Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB), Route de Lennik 808, 1070 Brussels, Belgium; [email protected] 2 Ministry of Health: Program of Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD) for Preventive Chemotherapy (PC), Gombe, Kinshasa, DRC; [email protected] (F.N.T.); [email protected] (D.M.) 3 Faculty of Medicine, School of Public Health, University of Kinshasa (UNIKIN), Lemba, Kinshasa, DRC; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +32-493-93-96-35 Received: 3 May 2019; Accepted: 30 May 2019; Published: 13 June 2019 Abstract: Here, we review all data available at the Ministry of Public Health in order to describe the history of the National Program for Onchocerciasis Control (NPOC) in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Discovered in 1903, the disease is endemic in all provinces. Ivermectin was introduced in 1987 as clinical treatment, then as mass treatment in 1989. Created in 1996, the NPOC is based on community-directed treatment with ivermectin (CDTI). In 1999, rapid epidemiological mapping for onchocerciasis surveys were launched to determine the mass treatment areas called “CDTI Projects”. CDTI started in 2001 and certain projects were stopped in 2005 following the occurrence of serious adverse events. Surveys coupled with rapid assessment procedures for loiasis and onchocerciasis rapid epidemiological assessment were launched to identify the areas of treatment for onchocerciasis and loiasis. -

WHO's Response to the 2018–2019 Ebola Outbreak in North Kivu and Ituri, the Democratic Republic of the Congo

WHO's response to the 2018–2019 Ebola outbreak in North Kivu and Ituri, the Democratic Republic of the Congo Report to donors for the period August 2018 – June 2019 2 | 2018-2019 North Kivu and Ituri Ebola virus disease outbreak: WHO report to donors © World Health Organization 2019 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo Complex Emergency 09-30-2013

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO - COMPLEX EMERGENCY FACT SHEET #3, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2013 SEPTEMBER 30, 2013 NUMBERS AT USAID/OFDA 1 F U N D I N G HIGHLIGHTS A GLANCE BY SECTOR IN FY 2013 U.S. Government (USG) provided nearly $165 million of humanitarian assistance in 6.4 5% the Democratic Republic of the Congo 7% 25% (DRC) in FY 2013 million 8% Insecurity and poor transportation People in Need of Food infrastructure continue to hinder and Agriculture Assistance 8% humanitarian access across eastern DRC U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) – August 2013 8% HUMANITARIAN FUNDING 23% TO DRC TO DATE IN FY 2013 16% 2.6 USAID/OFDA $48,352,484 USAID/FFP2 $56,471,800 million Health (25%) 3 Logistics & Relief Commodities (23%) State/PRM $60,045,000 Total Internally Displaced Water, Sanitation, & Hygiene (16%) Persons (IDPs) in the DRC Economic Recovery & Market Systems (8%) U.N. – August 2013 Humanitarian Coordination & Information Management (8%) $164,869,284 Agriculture & Food Security (8%) TOTAL USAID AND STATE Protection (7%) HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO DRC 434,306 Other (5%) Congolese Refugees in Africa Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees KEY DEVELOPMENTS (UNHCR) – August 2013 During FY 2013, violence intensified and humanitarian conditions deteriorated across eastern DRC, with the spread of a secessionist movement in Katanga Province, escalating 185,464 clashes and related displacement in Orientale Province, and worsening instability resulting Total Refugees in the DRC in tens of thousands of new displacements in North Kivu and South Kivu provinces. UNHCR – August 2013 Conflict continues to cause displacement, raise protection concerns, and constrain humanitarian access to populations in need of assistance. -

Human Rights Watch

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH LEAVE NO ONE BEHIND Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Emergencies Copyright © 2016 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-33498 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez. Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org LEAVE NO ONE BEHIND Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Emergencies SUMMARY ...............................................................................................................................= RECOMMENDATIONS ...............................................................................................................? ABANDONMENT AND OBSTACLES IN FLEEING ............................................................................;; ACCESS TO FOOD, SANITATION, AND MEDICAL SERVICES ..........................................................;> ACCESS TO EDUCATION -

Violence and Instability in Ituri

Violence and Instability in Ituri DJUGU’S MYSTIC CRISIS AND THE CAMOUFLAGE OF ETHNIC CONFLICT Amir Sungura, Limbo Kitonga, Bernard van Soest and Ndakasi Ndeze INSECURE LIVELIHOODS SERIES / JULY 2020 Photo cover: Internally displaced people in Drodro, Ituri ©️ John Wessels Violence and Instability in Ituri DJUGU’S MYSTIC CRISIS AND THE CAMOUFLAGE OF ETHNIC CONFLICT Amir Sungura, Limbo Kitonga, Bernard van Soest and Ndakasi Ndeze Executive summary This report analyses the string of attacks in and around Djugu territory in Ituri since late 2017. Based on both historical and recent conflict analysis, it finds recent and concrete triggers of the ongoing crisis, nonetheless rooted in protracted tension over land, livelihood and territory, often framed in ethnic binaries. Situated in a geopolitically strategic – but contested – area and shaped by eastern Congo’s broader security challenges, the Djugu crisis quickly escalated, with hundreds killed and half a million displaced. While the bulk of the violence seem to be driven by CODECO, an opaque mystico- armed movement, the government-led response rather com- plicated than attenuated violence. This report demonstrates that peace building in Djugu depends on deeper understanding of conflict dynamics and requires addressing political manipulation. Stabilisation efforts thus need to be embedded in broad strategies to address longstanding tension over land and identity. VIOLENCE AND INSTABILITY IN ITURI 4 Table of Contents 1 | INTRODUCTION 6 2 | BACKGROUND TO THE CURRENT CONFLICT 8 2.1 Ituri in -

Book XVIII Prizes and Organizations Editor: Ramon F

8 88 8 88 Organizations 8888on.com 8888 Basic Photography in 180 Days Book XVIII Prizes and Organizations Editor: Ramon F. aeroramon.com Contents 1 Day 1 1 1.1 Group f/64 ............................................... 1 1.1.1 Background .......................................... 2 1.1.2 Formation and participants .................................. 2 1.1.3 Name and purpose ...................................... 4 1.1.4 Manifesto ........................................... 4 1.1.5 Aesthetics ........................................... 5 1.1.6 History ............................................ 5 1.1.7 Notes ............................................. 5 1.1.8 Sources ............................................ 6 1.2 Magnum Photos ............................................ 6 1.2.1 Founding of agency ...................................... 6 1.2.2 Elections of new members .................................. 6 1.2.3 Photographic collection .................................... 8 1.2.4 Graduate Photographers Award ................................ 8 1.2.5 Member list .......................................... 8 1.2.6 Books ............................................. 8 1.2.7 See also ............................................ 9 1.2.8 References .......................................... 9 1.2.9 External links ......................................... 12 1.3 International Center of Photography ................................. 12 1.3.1 History ............................................ 12 1.3.2 School at ICP ........................................