Violence and Instability in Ituri

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Addressing Root Causes of Conflict: a Case Study Of

Experience paper Addressing root causes of conflict: A case study of the International Security and Stabilization Support Strategy and the Patriotic Resistance Front of Ituri (FRPI) in Ituri Province, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo Oslo, May 2019 1 About the Author: Ingebjørg Finnbakk has been deployed by the Norwegian Resource Bank for Democracy and Human Rights (NORDEM) to the Stabilization Support Unit (SSU) in MONUSCO from August 2016 until February 2019. Together with SSU Headquarters and Congolese partners she has been a key actor in developing and implementing the ISSSS program in Ituri Province, leading to a joint MONUSCO and Government process and strategy aimed at demobilizing a 20-year-old armed group in Ituri, the Patriotic Resistance Front of Ituri (FRPI). The views expressed in this report are her own, and do not represent those of either the UN or the Norwegian Refugee Council/NORDEM. About NORDEM: The Norwegian Resource Bank for Democracy and Human Rights (NORDEM) is NORCAP’s civilian capacity provider specializing in human rights and support for democracy. NORDEM has supported the SSU with personnel since 2013, hence contribution significantly with staff through the various preparatory phases as well as during the implementation. Acknowledgements: Reaching the point of implementing ISSSS phase two programs has required a lot of analyses, planning and stakeholder engagement. The work presented in this report would not be possible without all the efforts of previous SSU staff under the leadership of Richard de La Falaise. The FRPI process would not have been possible without the support and visions from Francois van Lierde (deployed by NORDEM) and Frances Charles at SSU HQ level. -

A Life of Fear and Flight

A LIFE OF FEAR AND FLIGHT The Legacy of LRA Brutality in North-East Democratic Republic of the Congo We fled Gilima in 2009, as the LRA started attacking there. From there we fled to Bangadi, but we were confronted with the same problem, as the LRA was attacking us. We fled from there to Niangara. Because of insecurity we fled to Baga. In an attack there, two of my children were killed, and one was kidnapped. He is still gone. Two family members of my husband were killed. We then fled to Dungu, where we arrived in July 2010. On the way, we were abused too much by the soldiers. We were abused because the child of my brother does not understand Lingala, only Bazande. They were therefore claiming we were LRA spies! We had to pay too much for this. We lost most of our possessions. Once in Dungu, we were first sleeping under a tree. Then someone offered his hut. It was too small with all the kids, we slept with twelve in one hut. We then got another offer, to sleep in a house at a church. The house was, however, collapsing and the owner chased us. He did not want us there. We then heard that some displaced had started a camp, and that we could get a plot there. When we had settled there, it turned out we had settled outside of the borders of the camp, and we were forced to leave. All the time, we could not dig and we had no access to food. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #2

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO - COMPLEX EMERGENCY FACT SHEET #2, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2018 MARCH 9, 2018 NUMBERS AT USAID/OFDA1 FUNDING HIGHLIGHTS BY SECTOR IN FY 2017–2018 A GLANCE • Conflict continues to displace 3% 3% populations within DRC and to 6% neighboring countries 6% 13.1 34% • requestsUN nearly $1.7 billion to meet 7% humanitarian needs in DRC during million 2018 People in DRC Requiring 18% • Cholera and polio type 2 remain critical Humanitarian Assistance 23% in 2018 health concerns UN – December 2017 Logistics Support & Relief Commodities (34%) Health (23%) HUMANITARIAN FUNDING Water, Sanitation & Hygiene (18%) FOR THE DRC RESPONSE IN FY 2017–2018 Protection (7%) Humanitarian Coordination & Information Management (6%) 7.7 Agriculture & Food Security (6%) USAID/OFDA $52,686,506 Nutrition (3%) million Other (3%) USAID/FFP $77,115,857 Acutely Food-Insecure 2 3 People in DRC USAID/FFP FUNDING State/PRM $62,496,034 UN – August 2017 BY MODALITY IN FY 2017–2018 48% 39% 11% 2% Local & Regional Procurement (48%) $192,298,397 U.S. In-Kind Food Aid (39%) 4.5 Cash Transfers for Food (11%) Complementary Services (2%) million IDPs in DRC UN – December 2017 KEY DEVELOPMENTS • The 2018 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) requests nearly $1.7 billion to provide humanitarian assistance to 10.5 million of the estimated 13.1 million people in need in 684,000 Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The 2018 appeal is the largest to date for DRC and reflects the widening scope of emergency needs in the country. DRC Refugees and Asylum-Seekers Across • Conflict continues to drive population displacement in DRC, with the UN projecting up Africa to 2.4 million new internally displaced persons (IDPs) by the end of 2018. -

UN Security Council, Children and Armed Conflict in the DRC, Report of the Secretary General, October

United Nations S/2020/1030 Security Council Distr.: General 19 October 2020 Original: English Children and armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Report of the Secretary-General Summary The present report, submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 1612 (2005) and subsequent resolutions, is the seventh report of the Secretary-General on children and armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It covers the period from 1 January 2018 to 31 March 2020 and the information provided focuses on the six grave violations committed against children, the perpetrators thereof and the context in which the violations took place. The report sets out the trends and patterns of grave violations against children by all parties to the conflict and provides details on progress made in addressing grave violations against children, including through action plan implementation. The report concludes with a series of recommendations to end and prevent grave violations against children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and improve the protection of children. 20-13818 (E) 171120 *2013818* S/2020/1030 I. Introduction 1. The present report, submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 1612 (2005) and subsequent resolutions, is the seventh report of the Secretary-General on children and armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and covers the period from 1 January 2018 to 31 March 2020. It contains information on the trends and patterns of grave violations against children since the previous report (S/2018/502) and an outline of the progress and challenges since the adoption by the Working Group on Children and Armed Conflict of its conclusions on children and armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in July 2018 (S/AC.51/2018/2). -

Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks and Other Emergencies

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 28: 05 - 11 July 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 11 July 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 1 117 106 12 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 146 082 3 836 Algeria ¤ 1 034 0 6 328 185 Mauritania 1 313 74 14 463 528 48 0 110 0 46 175 1 194 Niger 21 672 489 6 284 29 Mali 21 0 9 0 Cape Verde 6 471 16 4 954 174 Chad Eritrea Senegal 5 538 194 Gambia 66 0 33 006 289 1 414 8 Guinea-Bissau 847 17 Burkina Faso 2 060 56 277 071 4 343 168 552 2 124 Guinea 13 509 168 13 0 3 947 70 2 2 Benin 198 0 Nigeria 1 286 4 61 0 30 0 Ethiopia 13 2 6 995 50 556 5 872 15 Sierra Leone Togo 626 0 80 858 1 324 Ghana 7 142 98 Côte d'Ivoire 10 879 117 19 000 304 81 0 45 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 1 313 2 0 25 0 50 14 0 97 585 801 6 738 221 Cameroon 24 117 299 3 0 48 776 318 35 339 197 7 0 58 0 199 2 1 411 30 9 1 620 1 188 754 3 722 2 0 168 0 1 1 6 031 112 14 270 133 8 790 122 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 867 2 827 9 Sao Tome and Principe 4 0 5 215 144 716 494 198 87 277 2 104 Kenya Gabon Legend Congo 3 516 93 305 26 Rwanda 8 199 104 2 392 37 48 244 560 25 164 162 Democratic Republic of the Congo 12 790 167 Burundi Measles Humanitarian crisis 5 686 8 Seychelles 44 139 980 436 0 693 57 Monkeypox Yellow fever United Republic of Tanzania 197 0 16 957 68 Meningitis Lassa fever 509 21 241 1 6 257 229 Leishmaniasis Cholera 39 958 935 175 729 2 822 Comoros Plague 304 3 cVDPV2 Angola Malawi Diarrhoeal disease in children under five years 36 926 1 250 -

Democratic Republic of Congo

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 11 (A) - July 2003 I hid in the mountains and went back down to Songolo at about 3:00 p.m. I saw many people killed and even saw traces of blood where people had been dragged. I counted 82 bodies most of whom had been killed by bullets. We did a survey and found that 787 people were missing – we presumed they were all dead though we don’t know. Some of the bodies were in the road, others in the forest. Three people were even killed by mines. Those who attacked knew the town and posted themselves on the footpaths to kill people as they were fleeing. -- Testimony to Human Rights Watch ITURI: “COVERED IN BLOOD” Ethnically Targeted Violence In Northeastern DR Congo 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] “You cannot escape from the horror” This story of fifteen-year-old Elise is one of many in Ituri. She fled one attack after another and witnessed appalling atrocities. Walking for more than 300 miles in her search for safety, Elise survived to tell her tale; many others have not. -

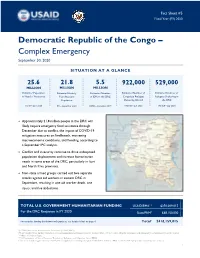

DRC Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #5 09.30.2020

Fact Sheet #5 Fiscal Year (FY) 2020 Democratic Republic of the Congo – Complex Emergency September 30, 2020 SITUATION AT A GLANCE 25.6 21.8 5.5 922,000 529,000 MILLION MILLION MILLION Estimated Population Estimated Acutely Estimated Number Estimated Number of Estimated Number of in Need of Assistance Congolese Refugees Refugees Sheltering in Food Insecure of IDPs in the DRC Population Sheltering Abroad the DRC OCHA – June 2020 UNHCR – July 2020 UNHCR – July 2020 IPC – September 2020 OCHA – December 2019 Approximately 21.8 million people in the DRC will likely require emergency food assistance through December due to conflict, the impact of COVID-19 mitigation measures on livelihoods, worsening macroeconomic conditions, and flooding, according to a September IPC analysis. Conflict and insecurity continue to drive widespread population displacement and increase humanitarian needs in some areas of the DRC, particularly in Ituri and North Kivu provinces. Non-state armed groups carried out two separate attacks against aid workers in eastern DRC in September, resulting in one aid worker death, one injury, and five abductions. TOTAL U.S. GOVERNMENT HUMANITARIAN FUNDING USAID/BHA1,2 $350,009,015 For the DRC Response in FY 2020 State/PRM3 $68,150,000 For complete funding breakdown with partners, see detailed chart on page 6 Total4 $418,159,015 1USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA) 2 Total USAID/BHA funding includes non-food humanitarian assistance from the former Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance and emergency food assistance from the former Office of Food for Peace. 3 U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (State/PRM) 4 This total includes approximately $23,833,699 in supplemental funding through USAID/BHA and State/PRM for COVID-19 preparedness and response activities. -

Country Fact Sheet, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/Country Fact... Français Home Contact Us Help Search canada.gc.ca Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets Home Country Fact Sheet DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO April 2007 Disclaimer This document was prepared by the Research Directorate of the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment. All sources are cited. This document is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed or conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. For further information on current developments, please contact the Research Directorate. Table of Contents 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 2. POLITICAL BACKGROUND 3. POLITICAL PARTIES 4. ARMED GROUPS AND OTHER NON-STATE ACTORS 5. FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS ENDNOTES REFERENCES 1. GENERAL INFORMATION Official name Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) Geography The Democratic Republic of the Congo is located in Central Africa. It borders the Central African Republic and Sudan to the north; Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda and Tanzania to the east; Zambia and Angola to the south; and the Republic of the Congo to the northwest. The country has access to the 1 of 26 9/16/2013 4:16 PM Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/Country Fact... Atlantic Ocean through the mouth of the Congo River in the west. The total area of the DRC is 2,345,410 km². -

Private Security Companies and Political Order in Congo

Private security companies and political order in Congo A HISTORY OF EXTRAVERSION Peer Schouten Private security companies and political order in Congo A history of extraversion Peer Schouten Doctoral Dissertation in Peace and Development Research School of Global Studies University of Gothenburg (June 5, 2014) © Peer Schouten Cover layout & illustration: Socrates Schouten Photo sources: private security guards and police officer against Goma background. (Peer Schouten, 2010/2012) Printing: Ineko, Gothenburg, 2014 ISBN: 978-91-628-9093-1 http://hdl.handle.net/2077/35683 ‘Un scorpion se promène sur les rives du fleuve Zaïre à Kinshasa et aperçoit un crocodile prenant un bain de soleil. Eh, dit le scorpion au crocodile, peux-tu me prendre sur ton dos et m'amener sur l'autre rive a Brazzaville? Que non, répond le crocodile. Je te connais trop bien: tu seras sur mon dos, et une fois au milieu du fleuve, tu vas me piquer et nous allons couler tous les deux. Mais non, rétorque le scorpion! Comment ferais-je une chose aussi aberrante? Si je te pique et que nous coulons tous les deux, je n'arriverai jamais à Brazzaville où pourtant je veux me rendre. Bien raisonné, dit le crocodile, monte sur mon dos et je t'emmène à Brazzaville. Et voilà notre scorpion sur le dos du crocodile qui se met à nager en direction de l'autre rive. Arrivé au beau milieu du fleuve, le scorpion pique à mort le crocodile et tous les deux se mettent à couler. Alors le crocodile mourant s'écrie dans un dernier souffle: Qu'est-ce que c'est que cette affaire? Le scorpion à moitié mort de répondre: c'est le Zaïre, ne cherche pas à comprendre.’ Ilunga Kabongo (1984: 13) i Table of Contents Table of Contents ......................................................................................................... -

WHO's Response to the 2018–2019 Ebola Outbreak in North Kivu and Ituri, the Democratic Republic of the Congo

WHO's response to the 2018–2019 Ebola outbreak in North Kivu and Ituri, the Democratic Republic of the Congo Report to donors for the period August 2018 – June 2019 2 | 2018-2019 North Kivu and Ituri Ebola virus disease outbreak: WHO report to donors © World Health Organization 2019 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Post-Cold War U.S

Continuity and Change in U.S.-Congo Relations: A critical analysis of post-Cold War U.S. foreign policy toward Zaire-Democratic Republic of Congo by Annelisa Lindsay B.A. May 2009, The George Washington University A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Elliott School of International Affairs of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 20, 2012 Thesis Directed by Paul D. Williams Associate Professor of International Affairs © Copyright 2012 by Annelisa Lindsay All rights reserved ii Abstract Continuity and Change in U.S.-Congo Relations: A critical analysis of post-Cold War U.S. foreign policy toward Zaire-Democratic Republic of Congo At the end of the Cold War, a shifting global political climate began to change U.S. foreign policy. U.S. policymakers soon realized that the United States no longer needed to compete with the Soviet Union for influence around the world. New policy priorities took the place of competition in proxy wars, which meant that Africa began to suffer from declining geostrategic importance. Zaire, which had shared a ―special relationship‖ with the United States during the Cold War, was not exempt from the growing malaise in U.S. Africa policy. This study seeks to analyze the continuity or change in U.S. policy toward Zaire, now Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in the post-Cold War era by examining how different foreign policymaking institutions (White House, Congress, national security bureaucracy) directed the decision-making process to influence situations (routine, crisis, extended crisis) in U.S.-Congo relations from 1989 to 2003. -

Writenet Democratic Republic of The

writenet is a network of researchers and writers on human rights, forced migration, ethnic and political conflict WRITENET writenet is the resource base of practical management (uk) e-mail: [email protected] independent analysis DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO: PROSPECTS FOR PEACE AND NORMALITY A Writenet Report by François Misser commissioned by United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Emergency and Security Services March 2006 Caveat: Writenet papers are prepared mainly on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment. The papers are not, and do not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. The views expressed in the paper are those of the author and are not necessarily those of Writenet or Practical Management. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms ................................................................................................... i Executive Summary ................................................................................. ii 1 Introduction........................................................................................1 2 Recent Developments.........................................................................1 2.1 Political Developments.................................................................................1 2.2 Humanitarian and Security Developments ...............................................2 3 Overview of Political and Security Risk Factors