Burundi-SCD-Final-06212018.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Study of Master Plan for Port Sector in the Republic of Burundi

Ministry of Transport, Public Works and Equipment Burundi The Study of Master Plan for Port Sector in the Republic of Burundi Final Report (Summary) September 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY PADECO Co., Ltd. Nippon Koei Co. Ltd. International Development Center of Japan Incorporated EI JR 12-189 Ministry of Transport, Public Works and Equipment Burundi The Study of Master Plan for Port Sector in the Republic of Burundi Final Report (Summary) September 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY PADECO Co. Ltd. Nippon Koei Co. Ltd. International Development Center of Japan Incorporated The Study of Master Plan for Port Sector in the Republic of Burundi Summary Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms ................................................................................................. v 1. Introduction....................................................................................................................... 1 2. Socio/Economic Developments in Burundi ....................................................................... 1 2.1 Trend in Socio/Economic Status............................................................................... 1 2.2 Current Plans for Economic Development ................................................................ 2 3. Current Status of Port Sector of Burundi......................................................................... 3 3.1 Bujumbura Port ....................................................................................................... 3 3.2 Rumonge Port ......................................................................................................... -

Business Ethics As Field of Training, Teaching and Research in Francophone Africa

Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Original Business Ethics as field of training, teaching and Article research in Francophone Africa Liboire Kagabo Department of African Languages and Literature, University of Burundi, Burundi ABSTRACT This article has been written within the framework of the Global Survey of Business Ethics 2010. It is seemingly the first attempt to investigate Business Ethics as academic field in Francophone Africa. After a discussion of methodological considerations, the article provides an overview of how Business Ethics is distributed in Francophone Africa. Even though, it is not well established in that part of Africa, some interesting data have been found in some countries like Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ivory Coast, Rwanda and Senegal. Business Ethics has been investigated in three areas: teaching, training and research. In Francophone Africa, teaching Business Ethics does not seem to be a reality in traditional faculties of Economics, Management or Commerce. Training in Business Ethics, however, is a reality in Francophone Africa, notably with the non-governmental organizations that deal with political and economic governance, development, and women and gender issues. Research on Business Ethics can be found in journals, bulletins, consultancy reports, university term papers, seminars and colloquia as well as in books. Key words: Business Ethics, Teaching, Training, Research, Francophone Africa INTRODUCTION Madagascar. For the purpose of the survey some French speaking countries in West For the purpose of the Global Survey of Africa, namely Cameroun, Tchad, Niger, Business Ethics 2010, the world was divided Benin and Togo was however included in into nine world regions, one of which was the the West African region. -

Burundi: Administrative Map May 2015

Burundi: Administrative Map May 2015 Kalehe Muhanga Rwamagana Nguzi Gishyita Kamonyi Karagwe Idjwi Karongi Muleba Ruhango EST Ngoma Birenga Kalehe Bugesera Kirehe Sengerema RWANDA MWANZA Cyesha Nyanza Nyanza Nyamasheke OUEST Nyamagabe SUD Nyamahale Kabare Kabare Kirehe Ngara Cyangugu Shabunda Bukavu Huye Rusizi KIRUNDO Butare Nyango Walungu Kibeho Gisagara Kirundo Nyabugombe Biharamulo NgaraKAGERA Itari Nyaruguru Walungu Biharamulo MUYINGA Keza Nyakahura CIBITOKE NGOZI Muyinga Geita Cibitoke Kayanza Ngozi Mu Rusagamba Nyaruonga Chato Mwenga KAYANZA Karuzi Bubanza Nyantwiga Ruamagaza LEGEND BUBANZA KARUZI CANKUZO International boundary Uvira Cakuzo MURAMVYA Kakonko 1st admin boundary Kakonko BUJUMBURA Muramvya 2nd admin boundaryMbogwe SUD-KIVU Musasa Undetermined boundary Mwenga MAIRIE BURUNDI Major road Uvira Bujumbura Gitega RUYIGI Main river Ruyigi GEITA DEMOCRATIC MWARO GITEGA Mugunzu Ocean / lake BUJUMBURA Major town REPUBLIC OF RURAL Kibondo Airport/ Airstrip THE CONGO Kasana Bukombe Shabunda Kasulu BURURI Bururi RUTANA Rutana UNITED REPUBLIC Kahama OF TANZANIA SHINYANGA Kibondo Nyange Main Map 1:1,180,000 KIGOMA MAKAMBAMakamba Makere Fizi Fizi Lake Kasulu Date: May 2015 Mbirira Sources: Boundaries (ESRI/OCHA), Tanganyika roads (ESRI), settlements (OCHA), Buhigwe rivers and lakes (ESRI) Kaliua MANIEMA Munyegera Feedback: Manyovu Mugombe [email protected] Kabambare www.unocha.org/eastern-africa www.reliefweb.intTABORA The boundaries and names shown and the Kigoma Kasulu Township Authority designations used on this map do not Uyowaimply Mgende official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. . -

Integrated Regional Information Network (IRIN): Burundi

U.N. Department of Humanitarian Affairs Integrated Regional Information Network (IRIN) Burundi Sommaire / Contents BURUNDI HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT No. 4...............................................................5 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 26 July 1996 (96.7.26)..................................................9 Burundi-Canada: Canada Supports Arusha Declaration 96.8.8..............................................................11 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 14 August 1996 96.8.14..............................................13 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 15 August 1996 96.8.15..............................................15 Burundi: Statement by the US Catholic Conference and CRS 96.8.14...................................................17 Burundi: Regional Foreign Ministers Meeting Press Release 96.8.16....................................................19 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 16 August 1996 96.8.16..............................................21 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 20 August 1996 96.8.20..............................................23 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 21 August 1996 96.08.21.............................................25 Burundi: Notes from Burundi Policy Forum meeting 96.8.23..............................................................27 Burundi: IRIN Summary of Main Events for 23 August 1996 96.08.23................................................30 Burundi: Amnesty International News Service 96.8.23.......................................................................32 -

HIV DR in CENTRAL AFRICA

WHO HIVRESNET STEERING COMMITTEE MEETING, November 10–12, 2009, Geneva, Switzerland HIV DR in CENTRAL AFRICA Pr Belabbes Intercountry Support Team Central Africa COUNTRIES COVERED BY THE INTERCOUNTRY SUPPORT TEAM / CENTRAL AFRICA Angola Burundi Cameroon Central African Republic Chad Congo Democratic Republic of Congo Equatorial Guinea Gabon Rwanda Sao Tome & Principe HIV PREVALENCE AMONG THE POPULATION Legend Generalized epidemic in 10 <1% countries /11 1-5% >5% Excepted Sao Tome& Principe nd HIV PREVALENCE AMONG PREGNANT WOMEN Legend <1% 1-5% >5% nd PATIENTS UNDER ART 2005-2008 70000 2005 2006 2007 2008 60000 50000 40000 30000 20000 10000 0 Angola Burundi Cameroon Congo Equatorial Gabon CAR DRC Rwanda Sao Tome Guinea Source of data Towards universal access: scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector. WHO, UNAIDS,UNICEF;September 2009. Training on HIVDR Protocols ANGOLA BURUNDI CAMEROON CENTRAL AFRICA REPUBLIC CHAD CONGO DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC CONGO EQUATORIAL GUINEA GABON RWANDA SAO TOME&PRINCIPE Training on HIVDR Protocols Douala, Cameroon 27-29 April 2009 The opening ceremony Participants to the Training on HIVDR Protocols, Douala Cameroon 27-29 April 2009 ON SITE STRENGTHENING CAPACITIES OF THE TECHNICAL WORKING GROUPS ANGOLA BURUNDI CAMEROON CENTRAL AFRICA REPUBLIC CHAD EQUATORIAL GUINEA RWANDA TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PROVIDED TO DEVELOP HIVDR PROTOCOLS ANGOLA BURUNDI CAMEROON CENTRAL AFRICA REPUBLIC CHAD EQUATORIAL GUINEA RWANDA EARLY WARNING INDICATORS BURUNDI : EWI abstraction in 19 sites (October) using paper-based. -

Researching Education Outcomes in Burundi, Malawi, Senegal and Uganda: Using Participatory Tools and Collaborative Approaches

Researching education outcomes in Burundi, Malawi, Senegal and Uganda: using participatory tools and collaborative approaches Dr. Karen Edge Akanksha A. Marphatia Elise Legault David Archer The Improving Learning Outcomes in Primary Schools (ILOPS) Project | Project methodology Funding: The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation in partnership with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation May 2010 © Institute of Education and ActionAid Table of Contents Section Page Executive summary 6 Context 8 Section 1 Current knowledge 11 Current knowledge on participatory approaches involving stakeholders to address children's learning 11 Implications of literature review on the ILOPS collaborative approach 11 Section 2 Building ILOPS partnerships 12 Recruiting the international, national and local researchers 12 The constituencies involved in multi-stakeholder research teams 13 Strategies for coordinating national-level team involvement 15 Section 3 Designing the ILOPS research framework 17 Pre-workshop activities and agenda setting 17 Workshop 1 – the Sesse cross-country research design workshop 18 Mapping expertise: what makes a good research team? 20 Developing the ILOPS conceptual framework 22 Focusing the ILOPS research 23 Generating and testing interview instruments 24 Next steps 25 Section 4 In-country data collection, analysis and validation process 26 Research process 26 In-country data analysis and validation workshops 27 Section 5 Cross-country findings 28 Workshop 2: Discussing cross-country findings 28 Section 6 Lessons learned on collaborative -

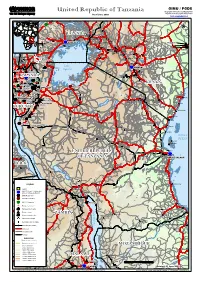

United Republic of Tanzania Geographic Information and Mapping Unit Population and Geographic Data Section As of June 2003 Email : [email protected]

GIMU / PGDS United Republic of Tanzania Geographic Information and Mapping Unit Population and Geographic Data Section As of June 2003 Email : [email protected] Soroti Masindi ))) ))) Bunia ))) HoimaHoima CCCCC CCOpiOpi !!! !! !!! !! !!! !! Mbale 55 !! 5555 55 Kitale !! 5555 Fort Portal UGANDAUGANDA !! CC !! Tororo !! ))) ))) !! ))) Bungoma !! !! Jinja CCCCCSwesweSweswe ))) Isiolo Tanzania_Atlas_A3PC.WOR CC ))) CC ))) KAMPALAKAMPALA ))) Kakamega DagahaleyDagahaley ))) Butembo !! ))) !! Entebbe Kisumu ))) Thomsons Falls!! Nanyuki IfoIfoIfo KakoniKakoni ))) !! ))) ))) ))) HagaderaHagadera ))) Lubero Londiani ))) DadaabDadaab Kabatoro ))) Molo ))) !! Nakuru ))) Bingi Elburgon !! Nyeri Gilgil ))) !! Embu CC))) MbararaMbarara Kinyasano CCMbararaMbarara !! Kisii ))) Naivasha ))) Fort Hall ))) )))) Nyakibale CCSettlementSettlement ))) CCCKifunzoKifunzo Makiro ))) Rutshuru ))) Thika ))) Kabale ))) ))) Lake ))) ))) Bukoba NAIROBINAIROBI Kikungiri Victoria ))) ))) ))) ))) MwisaMwisa Athi River !! GisenyiGisenyi ))) MwisaMwisa !! ))) ByumbaByumba Machakos yy!!))) Goma ))) Kajiado RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA Magadi ))) KIGALIKIGALI KibuyeKibuye ))) KibungoKibungo ))) KibungoKibungo KENYAKENYA ))) KENYAKENYA ))) KENYAKENYA ))) KENYAKENYA ))) KENYAKENYA ))) GikongoroGikongoro NgaraNgara))) ))) NgaraNgara ))) !! ))) LukoleLukole A&BA&B MwanzaMwanza !! )))LukoleLukole A&BA&B MuganoMugano ))) )))MbubaMbuba SongoreSongore ))) ))) Ngozi ))) MuyingaMuyinga ))) Nyaruonga -

Rumonge – Rutunga -Bujumbura Section

Language: English Original: English PROJECT: MULTINATIONAL: TANZANIA –BURUNDI ROAD PROJECT. RAP summary RN3: RUMONGE – RUTUNGA -BUJUMBURA SECTION COUNTRIES: TANZANIA-BURUNDI Team Leader: J. NDIKUMWAMI, Senior Transport Engineer, PICU.1/COBI Co-Team Leader: J. B AGUMA, PRINCIPAL Transport Economist, RDGE.4 P. KANYIMBO, Regional Integration Coordinator, RDGE0 Preparation Team E&S Team Members: P. HORUGAVYE, Chief socio-economist, RDGC4 /SNSC F. KAYIGAMBA, Environmental expert, Consultant SNSC E.B. KAHUBIRE, Social Development Officer, RDGE4 /SNSC Date: July 2018 Multinational Tanzania –Burundi road project. RAP summary Project Title: Rehabilitation of Bujumbura – Rumonge Road Section Country: Burundi Department: RDGE Division: RDGE 3 Project Category: 1 1. INTRODUCTION The Rumonge - Bujumbura road section is one of the EAC roads under the Multi-National Tanzania/Burundi: Nyakanazi-Kasulu-Manyovu/Rumonge-Rutunga-Bujumbura Road Project. The Project objective is to rehabilitate and upgrade the existing Rumonge–Bujumbura road (78km) section to bituminous that conform to East African Community standards with the aim of enhancing trade, transport and tourism in the East African Region as well as improving socioeconomic conditions for the population along Lake Tanganyika. The project is being implemented by EAC through Burundian Office of Roads (Office des Routes – OdR). OdR, under the Ministry of Transport, Public Works, and Equipment is the roads authority of Burundi. The importance of the project road lays on the fact that apart from linking Burundi with Tanzania, the road provides transportation route for agricultural and mining produce to and from the Great Lakes countries in particular the eastern DRC. The project shall ultimately improve life for the population along Lake Tanganyika, this road being a driver of the economy of the Great Lakes countries and Burundi in particular, along the Central Trade Corridor. -

Transaction Costs and Smallholder Farmers' Participation in Banana

Center of Evaluation for Global Action Working Paper Series Agriculture for Development Paper No. AfD-0909 Issued in July 2009 Transaction Costs and Smallholder Farmers’ Participation in Banana Markets in the Great Lakes Region John Jagwe Emily Ouma Charles Machethe University of Pretoria International Institute of Tropical Agriculture This paper is posted at the eScholarship Repository, University of California. http://repositories.cdlib.org/cega/afd Copyright © 2009 by the author(s). Series Description: The CEGA AfD Working Paper series contains papers presented at the May 2009 Conference on “Agriculture for Development in Sub-Saharan Africa,” sponsored jointly by the African Economic Research Consortium (AERC) and CEGA. Recommended Citation: Jagwe, John; Ouma, Emily; Machethe, Charles. (2009) Transaction Costs and Smallholder Farmers’ Participation in Banana Markets in the Great Lakes Region. CEGA Working Paper Series No. AfD-0909. Center of Evaluation for Global Action. University of California, Berkeley. Transaction Costs and Smallholder Farmers’ Participation in Banana Markets in the Great Lakes Region John Jagwe1, 2, Emily Ouma2, Charles Machethe1 1Department of Agricultural Economics, Extension and Rural Development, University of Pretoria (LEVLO, 002, Pretoria, South Africa); 2International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, Burundi, c/o IRAZ, B.P. 91 Gitega Keywords: smallholder farmers, market participation, transaction costs, bananas Abstract. This article analyses the determinants of the discrete decision of a household on whether to participate in banana markets using the FIML bivariate probit method. The continuous decision on how much to sell or buy is analyzed by establishing the supply and demand functions while accounting for the selectivity bias. Results indicate that buying and selling decisions are not statistically independent and the random disturbances in the buying and selling decisions are affected in opposite directions by random shocks. -

The Burundi Peace Process

ISS MONOGRAPH 171 ISS Head Offi ce Block D, Brooklyn Court 361 Veale Street New Muckleneuk, Pretoria, South Africa Tel: +27 12 346-9500 Fax: +27 12 346-9570 E-mail: [email protected] Th e Burundi ISS Addis Ababa Offi ce 1st Floor, Ki-Ab Building Alexander Pushkin Street PEACE CONDITIONAL TO CIVIL WAR FROM PROCESS: THE BURUNDI PEACE Peace Process Pushkin Square, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Th is monograph focuses on the role peacekeeping Tel: +251 11 372-1154/5/6 Fax: +251 11 372-5954 missions played in the Burundi peace process and E-mail: [email protected] From civil war to conditional peace in ensuring that agreements signed by parties to ISS Cape Town Offi ce the confl ict were adhered to and implemented. 2nd Floor, Armoury Building, Buchanan Square An AU peace mission followed by a UN 160 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock, South Africa Tel: +27 21 461-7211 Fax: +27 21 461-7213 mission replaced the initial SA Protection Force. E-mail: [email protected] Because of the non-completion of the peace ISS Nairobi Offi ce process and the return of the PALIPEHUTU- Braeside Gardens, Off Muthangari Road FNL to Burundi, the UN Security Council Lavington, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254 20 386-1625 Fax: +254 20 386-1639 approved the redeployment of an AU mission to E-mail: [email protected] oversee the completion of the demobilisation of ISS Pretoria Offi ce these rebel forces by December 2008. Block C, Brooklyn Court C On 18 April 2009, at a ceremony to mark the 361 Veale Street ON beginning of the demobilisation of thousands New Muckleneuk, Pretoria, South Africa DI Tel: +27 12 346-9500 Fax: +27 12 460-0998 TI of PALIPEHUTU-FNL combatants, Agathon E-mail: [email protected] ON Rwasa, leader of PALIPEHUTU-FNL, gave up AL www.issafrica.org P his AK-47 and military uniform. -

Land Reform in Burundi: Waiting for Change After Twenty Years of Fruitless Debate

Dominik Kohlhagen [email protected] Land reform in Burundi: Waiting for change after twenty years of fruitless debate INTRODUCTION Burundi is a landlocked country in East Africa, neighboring Rwanda, Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of Congo. With its 8,5 million inhabitants living on 28,000 square kilometres, it is comparable in size and inhabitants to Belgium or Catalonia. In Africa, it is the second most densely populated country after Rwanda. Its economy heavily depends on the agricultural sector and relies to a large extent on subsistence farming. Since independence from Belgium in 1962, Burundi has experienced several outbreaks of violence. Important interethnic massacres occurred in 1965, 1969, 1972, 1988 and 1991. Between 1993 and 2005, a civil war has caused hundreds of thousands of deaths. At all these occasions, people were displaced or had to seek refuge in neighboring countries, leaving behind their land and livestock. Following a relative political and military stabilization, many refugees have recently returned to Burundi and are now trying to recover their land. Demands for land or compensation by returning refugees are currently adding to many other problems caused by land scarcity and inappropriate land laws. The current land code of Burundi, which was promulgated only in 1986, is mainly a compilation of former colonial laws and retained most of the shortcomings of preceding texts. Under the 1986 code, the country saw a significant increase in land conflicts and many illegal land allocations. A reform of the land code has been discussed by government officials and international donors since the 1990s. But up to now, all these discussions proved fruitless. -

An Estimated Dynamic Model of African Agricultural Storage and Trade

High Trade Costs and Their Consequences: An Estimated Dynamic Model of African Agricultural Storage and Trade Obie Porteous Online Appendix A1 Data: Market Selection Table A1, which begins on the next page, includes two lists of markets by country and town population (in thousands). Population data is from the most recent available national censuses as reported in various online databases (e.g. citypopulation.de) and should be taken as approximate as census years vary by country. The \ideal" list starts with the 178 towns with a population of at least 100,000 that are at least 200 kilometers apart1 (plain font). When two towns of over 100,000 population are closer than 200 kilometers the larger is chosen. An additional 85 towns (italics) on this list are either located at important transport hubs (road junctions or ports) or are additional major towns in countries with high initial population-to-market ratios. The \actual" list is my final network of 230 markets. This includes 218 of the 263 markets on my ideal list for which I was able to obtain price data (plain font) as well as an additional 12 markets with price data which are located close to 12 of the missing markets and which I therefore use as substitutes (italics). Table A2, which follows table A1, shows the population-to-market ratios by country for the two sets of markets. In the ideal list of markets, only Nigeria and Ethiopia | the two most populous countries | have population-to-market ratios above 4 million. In the final network, the three countries with more than two missing markets (Angola, Cameroon, and Uganda) are the only ones besides Nigeria and Ethiopia that are significantly above this threshold.