Transaction Costs and Smallholder Farmers' Participation in Banana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burundi-SCD-Final-06212018.Pdf

Document of The World Bank Report No. 122549-BI Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF BURUNDI ADDRESSING FRAGILITY AND DEMOGRAPHIC CHALLENGES TO REDUCE POVERTY AND BOOST SUSTAINABLE GROWTH Public Disclosure Authorized SYSTEMATIC COUNTRY DIAGNOSTIC June 15, 2018 Public Disclosure Authorized International Development Association Country Department AFCW3 Africa Region International Finance Corporation (IFC) Sub-Saharan Africa Department Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) Sub-Saharan Africa Department Public Disclosure Authorized BURUNDI - GOVERNMENT FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective as of December 2016) Currency Unit = Burundi Franc (BIF) US$1.00 = BIF 1,677 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ACLED Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project AfDB African Development Bank BMM Burundi Musangati Mining CE Cereal Equivalent CFSVA Comprehensive Food Security and Vulnerability Assessment CNDD-FDD Conseil National Pour la Défense de la Démocratie-Forces pour la Défense de la Démocratie (National Council for the Defense of Democracy-Forces for the Defense of Democracy) CPI Consumer Price Index CPIA Country Policy and Institutional Assessment DHS Demographic and Health Survey EAC East African Community ECVMB Enquête sur les Conditions de Vie des Menages au Burundi (Survey on Household Living Conditions in Burundi) ENAB Enquête Nationale Agricole du Burundi (National Agricultural Survey of Burundi) FCS Fragile and conflict-affected situations FDI Foreign Direct Investment FNL Forces Nationales -

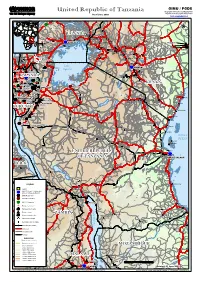

United Republic of Tanzania Geographic Information and Mapping Unit Population and Geographic Data Section As of June 2003 Email : [email protected]

GIMU / PGDS United Republic of Tanzania Geographic Information and Mapping Unit Population and Geographic Data Section As of June 2003 Email : [email protected] Soroti Masindi ))) ))) Bunia ))) HoimaHoima CCCCC CCOpiOpi !!! !! !!! !! !!! !! Mbale 55 !! 5555 55 Kitale !! 5555 Fort Portal UGANDAUGANDA !! CC !! Tororo !! ))) ))) !! ))) Bungoma !! !! Jinja CCCCCSwesweSweswe ))) Isiolo Tanzania_Atlas_A3PC.WOR CC ))) CC ))) KAMPALAKAMPALA ))) Kakamega DagahaleyDagahaley ))) Butembo !! ))) !! Entebbe Kisumu ))) Thomsons Falls!! Nanyuki IfoIfoIfo KakoniKakoni ))) !! ))) ))) ))) HagaderaHagadera ))) Lubero Londiani ))) DadaabDadaab Kabatoro ))) Molo ))) !! Nakuru ))) Bingi Elburgon !! Nyeri Gilgil ))) !! Embu CC))) MbararaMbarara Kinyasano CCMbararaMbarara !! Kisii ))) Naivasha ))) Fort Hall ))) )))) Nyakibale CCSettlementSettlement ))) CCCKifunzoKifunzo Makiro ))) Rutshuru ))) Thika ))) Kabale ))) ))) Lake ))) ))) Bukoba NAIROBINAIROBI Kikungiri Victoria ))) ))) ))) ))) MwisaMwisa Athi River !! GisenyiGisenyi ))) MwisaMwisa !! ))) ByumbaByumba Machakos yy!!))) Goma ))) Kajiado RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA Magadi ))) KIGALIKIGALI KibuyeKibuye ))) KibungoKibungo ))) KibungoKibungo KENYAKENYA ))) KENYAKENYA ))) KENYAKENYA ))) KENYAKENYA ))) KENYAKENYA ))) GikongoroGikongoro NgaraNgara))) ))) NgaraNgara ))) !! ))) LukoleLukole A&BA&B MwanzaMwanza !! )))LukoleLukole A&BA&B MuganoMugano ))) )))MbubaMbuba SongoreSongore ))) ))) Ngozi ))) MuyingaMuyinga ))) Nyaruonga -

An Estimated Dynamic Model of African Agricultural Storage and Trade

High Trade Costs and Their Consequences: An Estimated Dynamic Model of African Agricultural Storage and Trade Obie Porteous Online Appendix A1 Data: Market Selection Table A1, which begins on the next page, includes two lists of markets by country and town population (in thousands). Population data is from the most recent available national censuses as reported in various online databases (e.g. citypopulation.de) and should be taken as approximate as census years vary by country. The \ideal" list starts with the 178 towns with a population of at least 100,000 that are at least 200 kilometers apart1 (plain font). When two towns of over 100,000 population are closer than 200 kilometers the larger is chosen. An additional 85 towns (italics) on this list are either located at important transport hubs (road junctions or ports) or are additional major towns in countries with high initial population-to-market ratios. The \actual" list is my final network of 230 markets. This includes 218 of the 263 markets on my ideal list for which I was able to obtain price data (plain font) as well as an additional 12 markets with price data which are located close to 12 of the missing markets and which I therefore use as substitutes (italics). Table A2, which follows table A1, shows the population-to-market ratios by country for the two sets of markets. In the ideal list of markets, only Nigeria and Ethiopia | the two most populous countries | have population-to-market ratios above 4 million. In the final network, the three countries with more than two missing markets (Angola, Cameroon, and Uganda) are the only ones besides Nigeria and Ethiopia that are significantly above this threshold. -

The AU and the Search for Peace and Reconciliation in Burundi and Comoros

Th e AU and the search for Peace and Reconciliation in Burundi and Comoros The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD Centre) is an independent mediation organisation dedicated to helping improve the global response to armed confl ict. It attempts to achieve this by mediating between warring parties and providing support to the broader mediation community. The HD Centre is driven by humanitarian values and its ultimate goal to reduce the consequences of violent confl ict, improve security, and contribute to the peaceful resolution of confl ict. It maintains a neutral stance towards the warring parties that it mediates between and, in order to maintain its impartiality it is funded by a variety of governments, private foundations and philanthropists. © Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, 2011 Reproduction of all or part of this publication may be authorised only with written consent and acknowledgement of the source. Front cover photography: © African Union, 78th PSC Meeting on Comoros, 9 June 2007 | © Lt. TMN Turyamumanya / Afrian Union, TFG Soldiers in Somalia queue for their fi rst organised payment exercise supervised by AMISOM troops in Mogadishu | © African Union, Water provision to neighbouring villagers in Mogadishu Th e AU and the search for Peace and Reconciliation in Burundi and Comoros Table of contents Part I Foreword 02 Acknowledgements 04 — Burundi case study Introduction 05 Part I: Burundi case study 09 Part II Executive summary 09 1.1 Context 10 case study — Comoros 1.2 OAU/AU intervention in the Burundi crisis 12 Part II: Comoros -

Supplementary Material Barriers and Facilitators to Pre-Exposure

Sexual Health, 2021, 18, 130–39 © CSIRO 2021 https://doi.org/10.1071/SH20175_AC Supplementary Material Barriers and facilitators to pre-exposure prophylaxis among A frican migr ants in high income countries: a systematic review Chido MwatururaA,B,H, Michael TraegerC,D, Christopher LemohE, Mark StooveC,D, Brian PriceA, Alison CoelhoF, Masha MikolaF, Kathleen E. RyanA,D and Edwina WrightA,D,G ADepartment of Infectious Diseases, The Alfred and Central Clinical School, Monash Un iversity, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. BMelbourne Medical School, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. CSchool of Public Health and Preventative Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. DBurnet Institute, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. EMonash Infectious Diseases, Monash Health, Melbourne, Vi, Auc. stralia. FCentre for Culture, Ethnicity & Health, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. GPeter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic., Australia. HCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] File S1 Appendix 1: Syntax Usedr Dat fo abase Searches Appendix 2: Table of Excluded Studies ( n=58) and Reasons for Exclusion Appendix 3: Critical Appraisal of Quantitative Studies Using the ‘ Joanna Briggs Institute Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies’ (39) Appendix 4: Critical Appraisal of Qualitative Studies U sing a modified ‘CASP Qualitative C hecklist’ (37) Appendix 5: List of Abbreviations Sexual Health © CSIRO 2021 https://doi.org/10.1071/SH20175_AC Appendix 1: Syntax Used for Database -

Progress Report (2016–2018) of the MDB Working Group On

Progress Report (2016-2018) of the MDB Working Group on Sustainable Transport September 2019 Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 3 2 MDB ACTION ON SUSTAINABLE TRANSPORT: 2016 to 2018....................................... 4 3 SPECIAL FEATURE: MDB ENGAGEMENT IN ROAD SAFETY IMPROVEMENTS .......... 8 ANNEX: LENDING PROJECTS APPROVED BY EACH MDB ................................................11 African Development Bank ................................................................................................11 Asian Development Bank ...................................................................................................13 CAF – Development Bank of Latin America .......................................................................17 European Bank for Reconstruction and Development ........................................................19 European Investment Bank ................................................................................................22 Inter-American Development Bank ....................................................................................26 Islamic Development Bank ................................................................................................28 World Bank ........................................................................................................................29 Note: This is a joint document authored by members of the Multilateral Development -

Gender Equality in Burundi: Why Does Support Not Extend to Women's Right

Gender equality in Burundi: Why does support not extend to women’s right to inherit land? By Alain Ndikumana Afrobarometer Policy Paper No. 22 | July 2015 Introduction With 27,834 km² of surface area and a population of 10.5 million, Burundi’s population density is seven times that of Tanzania and second only to Rwanda’s on the African mainland (World Bank, 2014). Its population grows at an annual rate of 2.4%, and more than 90% of the population lives primarily on agriculture. These factors make land a vital and scarce resource in Burundi, leading to frequent conflicts and particular complications in questions of inheritance (Kazoviyo & Gahungu, 2011). The situation is even more problematic for women and girls, who traditionally inherit nothing from their fathers. In Burundi, women’s right to inherit land faces the triple barriers of demography, tradition, and the law. Promoting gender equality and especially women’s right to inherit land is a major focus of women’s-rights activists. Although Burundi has signed and incorporated in its constitution most international instruments promoting gender equality, women’s succession rights do not yet have full legal protection. Since 2004, government legislation on women’s inheritance laws awaits consideration by the National Assembly. “But problems related to the scarcity of land and overpopulation seem to veil the face of leaders who end up believing that a law on female succession would be a problem rather than a solution” (Kazoviyo & Gahungu, 2011, p. 1). Even if the proposed law is passed, evidence suggests that gender inequality in access to and control over land will remain a problem. -

Burundi Country Operational Plan (COP) 2019 Strategic Direction Summary 29 April 2019

Burundi Country Operational Plan (COP) 2019 Strategic Direction Summary 29 April 2019 Table of Contents 1.0 Goal Statement 2.0 Epidemic, Response, and Program Context 2.1 Summary statistics, disease burden and country profile 2.2 Investment profile 2.3 National sustainability profile update 2.4 Alignment of PEPFAR investments geographically to disease burden 2.5 Stakeholder engagement 3.0 Geographic and population prioritization 4.0 Program Activities for Epidemic Control in Scale-up Locations and Populations 4.1 Finding the missing, getting them on treatment, and retaining them 4.2 Prevention, specifically detailing programs for priority programming 4.3 Additional country-specific priorities listed in the planning level letter 4.4 Commodities 4.5 Collaboration, Integration, and Monitoring 4.6 Targets for scale-up locations and populations 5.0 Program Activities for Epidemic Control in Attained and Sustained Locations and Populations 5.1 COP19 programmatic priorities 5.2 Targets for attained and sustained locations and populations 5.3 Establishing service packages to meet targets in sustained provinces 6.0 Program Support Necessary to Achieve Sustained Epidemic Control 7.0 USG Management, Operations and Staffing Plan to Achieve Stated Goals Appendix A - Prioritization Appendix B - Budget Profile and Resource Projections Appendix C - Tables and Systems Investments for Section 6.0 Appendix D - Minimum Program Requirements Appendix E - Faith and Community Initiative (as applicable) Page | 2 Acronym List ABS Alliance Burundaise contre le -

Burundi: 110 Kv Line Bujumbara-Gitega Ex-Post

Burundi: 110 kV line Bujumbara-Gitega Ex-post evaluation OECD sector 23040 Power Transmission and Distribution BMZ project ID 1987 66 511 Project-executing agency Régie de Production et de Distribution d'Eau et d'Electricité (REGIDESO) Consultant Lahmeyer International GmbH, Frankfurt Büro Männlein, Kempten Year of ex-post evaluation 2005 Project appraisal Ex-post evaluation (planned) (actual) Start of implementation 05/1987 05/1987 Period of implementation Line: 35 months Line: 54 months Line: 72 months City grid: 24 months Investment costs EUR 9.7 million EUR 9.6 million Counterpart contribution EUR 1.6 million EUR 1.5 million Financing, of which Financial EUR 8.1 million EUR 8.1 million Cooperation (FC) funds Other institutions/donors involved none none Performance (overall rating) 5 Significance / relevance (sub-rating) 5 Effectiveness (sub-rating) 5 Efficiency (sub-rating) 5 Brief Description, Overall Objective and Project Objectives with Indicators The executing agency of the FC project was Régie de Production et de Distribution d'Eau et d'Electricité (REGIDESO), founded in 1968. It is in charge of the country's power and urban water supply and maintains a branch office in the project area (Gitega). The project served the purpose of providing cost-efficient and reliable power to meet the growing needs of the town of Gitega. As this is an economically important regional centre the target group was industry, public utilities and private consumers. The 110 kilovolt single line and a sub-station connected the city of Gitega to the transnational integrated network between the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda and Burundi. -

List of Participants

CBD Distr. CONVENTION ON GENERAL BIOLOGICAL UNEP/CBD/NBSAP/CBW-CAFR/1/ DIVERSITY ENGLISH ONLY Capacity-building Workshop for Central Africa on National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs) and Mainstreaming of Biodiversity Limbé, Cameroon, 22 - 25 September 2008 List of Participants Liste des Participants Lista de Participantes 22 October 2008 Convention on Biological Diversity List of Participants CBD Parties Belgium Cameroon 1. Dr. René-Marie Lafontaine 6. Ms. Colette Edith Ekobo Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (Belgium) Inspector Vautierstraat 29 Agricultural Development Brussels B-1000 Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development Belgium BP 25 184 E-Mail: [email protected] Yaoundé Web: http://www.biodiv.be Cameroon Tel.: +237 77 60 41 01 Burundi Fax: +237 22 22 16 33 E-Mail: [email protected] 2. Ms. Adelin Ntungumburanye Directeur général 7. Ebénézer Elimbi Institut National pour l'Environnement et la Conservation de la Nature Ministère Du Tourisme (INECN) Yaoundé BP 56 Cambodia Gitega Tel.: +237 99 76 54 81, 22 22 12 95 Burundi E-Mail: [email protected] Tel.: +257 22 40 30 31 Fax: +257 22 40 30 32 8. Mrs. Mary Fosi Mbantenkhu E-Mail: [email protected] Technical Advisor No. 1 - COP Bureau Member, NBFP Cabinet of the Minister Cameroon Ministry of Environment and Nature Protection Ministerial Building No. 2, 6th floor 3. Ebo Etienne Assoumou Door 636 DP MINEP SW Yaounde Cameroon Cameroon Tel.: +237 77 36 89 41 Tel.: +237 22 22 94 80 E-Mail: [email protected] Fax: +237 22 22 94 80 E-Mail: [email protected], [email protected] 4. -

Countries' Flags and Capitals

Countries’ Flags and Capitals Afghanistan Albania Algeria Andorra Angola Antigua Argentina Armenia Aruba Australia Austria Azerbaijan Bahamas Bahrain Bangladesh Barbados Andorra la Vella and Barbuda Kabul Tirana Algiers Luanda St. John’s Buenos Aires Yervan Oranjestad Canberra Vienna Baku Nassau Manama Dhaka Bridgetown Bosnia- Brunei Burkina Faso Belarus Belgium Belize Benin Bhutan Bolivia Botswana Brazil Bulgaria Burundi Cabo Verde Cambodia Cameroon Minsk Herzegovina Bandar Seri Ouagadougou Brussels Belmopan Porto-Novo Thimphu Sucre Sarajevo Gaborone Brasília Begawan Sofia Gitega Praia Phnom Penh Yaoundé Canada Central African Chad Chile China Colombia Cook Islands Comoros Costa Rica Croatia Cuba Cyprus Czech Republic Dominican Republic Democratic Denmark Santo Domingo Republic of Congo Republic Prague Copenhagen Ottawa Bangui N’Djamena Santiago Beijing Bogatá Avarua Moroni San José Zagreb Havana Nicosia Brazzaville Djibouti Dominica East Timor Ecuador El Salvador Egypt England Equatorial Guinea Eritrea Estonia Ethiopia Fiji Finland France Gabon Gambia Malabo Djibouti City Roseau Dili Quito San Salvador Cairo London Asmara Tallinn Addis Ababa Suva Helsinki Paris Libreville Banjul Georgia Germany Ghana Greece Grenada Guatemala Guernsey Guinea Guinea Bissau Guyana Haiti Honduras Hungary Iceland India Indonesia Tbilisi Berlin Accra Athens St. George’s Guatemala City Saint Peter Port Conakry Bissau Georgetown Port-au-Prince Tegucigalpa Budapest Reykjavik New Delhi Jakarta Iran Iraq Israel Italy Ivory Coast Jamaica Japan Jordan Kazakhstan -

TAXES in AFRICA 2021 2Nd EDITION

TAXES IN AFRICA 2021 2nd EDITION 24, Rue de Londres - 75009 Paris - France Tel: +33 (0) 1 44 15 95 23 - www.eaiinternational.org Taxes in Africa - Edition 2021• 253 Edition 2021 © Togo Alger Bamako Ouagadougou Abuja Djouba Kampala Gitega Capital city : Language : GDP/capita Telephone code : lomé French 2019 : +228 USD 679 Area : Political system : National day : 56,785 km2 Republic Currency : 27 April Franc CFA Population : (XOF) 8,608,444 ISO Code : Taxes in Africa - Edition 2021• 445 Edition 2021 © TGO 446 • Taxes in Africa - Edition 2021 Edition 2021 © Togo 1. Corporation tax 1.1 Tax base Public limited companies, joint stock companies with sole shareholders, simpli- fied joint stock companies, limited liability companies and sole proprietorships with limited liability where the sole proprietor is a legal entity are liable for cor- poration tax. The taxable profit is the net profit determined from the income from all opera- tions of all types carried out by companies, including in particular financial inco- me, capital gains from the disposal of assets during or at the end of operations and gains made upon the free revaluation of assets. 1.2 Residence and non-residence Corporation tax is owed only on profit made by companies operating in Togo and those where taxation is attributed to Togo under an international agreement on double taxation. The following are deemed to operate in Togo: - companies and other entities that are residents in Togo, that is to say whose registered office or effective place of management is located in Togo. - companies and other non-resident entities with a permanent establish- ment in Togo, subject to the provisions of international agreements on double taxation.