Reconciliation Process Challenges Learning from Past Experiences and Insights from the South African Reconciliation Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EDUAF Asbl 15Ans 2005-2020

EDUAF Asbl 15ans 2005-2020 Eduaf Luxembourg 2020 Dr Mélanie Bindariye-Ntahorutaba Présidente Edito 2005-2020 : 15 ans déjà ! Des convictions Le développement passera par une éducation bien pensée, généralisée et de qualité. Promouvoir une santé saine dans la société, notamment pour les apprenants, est un complément nécessaire à une éducation efficiente et efficace. Telles étaient les convictions du couple BINDARIYE Nelson – NTAHORUTABA Mélanie lors de la création d’EDUAF Luxembourg en 2005, et même avant. Leur long exil politique – 40 ans pour l’un, 34 pour l’autre - ne les a pas empêchés de rêver de progrès futurs de l’Afrique en général et du Burundi en particulier. Leurs formations et leur cheminement professionnels respectifs, à la base, psychopédagogue l’un et médecin pédiatre l’autre - ont nourri leurs réflexions. Quinze ans après la création d’EDUAF (Education Universelle en Afrique), leurs convictions et leur vision du développement n’ont pas changé. Elles se sont consolidées. Les enfants du couple n’ont pas tardé à les accompagner. Ils les soutiennent depuis longtemps. Ils sont d’ailleurs co-fondateurs d’EDUAF. Cette attitude positive des enfants a continuellement boosté l’action et la détermination des parents. Amis et connaissances Nombreux de leurs amis et connaissances ont écouté et compris les fondateurs d’EDUAF Luxembourg. Sans leurs contributions multifacettes, EDUAF Luxembourg n’aurait jamais pu autant progresser dans l’accomplissement de sa mission. Des progrès évidents Depuis 15 ans, EDUAF Luxembourg a réalisés 8 projets, tous dans les domaines de l’éducation et de la santé. Des bases solides pour le futur ont été jetés : des infrastructures ont été construites, de nombreux élèves et étudiants ont accomplis leur cycle respectif de formation, des élèves vulnérables bénéficient de conditions scolaires améliorées. -

Burundi-SCD-Final-06212018.Pdf

Document of The World Bank Report No. 122549-BI Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF BURUNDI ADDRESSING FRAGILITY AND DEMOGRAPHIC CHALLENGES TO REDUCE POVERTY AND BOOST SUSTAINABLE GROWTH Public Disclosure Authorized SYSTEMATIC COUNTRY DIAGNOSTIC June 15, 2018 Public Disclosure Authorized International Development Association Country Department AFCW3 Africa Region International Finance Corporation (IFC) Sub-Saharan Africa Department Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) Sub-Saharan Africa Department Public Disclosure Authorized BURUNDI - GOVERNMENT FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective as of December 2016) Currency Unit = Burundi Franc (BIF) US$1.00 = BIF 1,677 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ACLED Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project AfDB African Development Bank BMM Burundi Musangati Mining CE Cereal Equivalent CFSVA Comprehensive Food Security and Vulnerability Assessment CNDD-FDD Conseil National Pour la Défense de la Démocratie-Forces pour la Défense de la Démocratie (National Council for the Defense of Democracy-Forces for the Defense of Democracy) CPI Consumer Price Index CPIA Country Policy and Institutional Assessment DHS Demographic and Health Survey EAC East African Community ECVMB Enquête sur les Conditions de Vie des Menages au Burundi (Survey on Household Living Conditions in Burundi) ENAB Enquête Nationale Agricole du Burundi (National Agricultural Survey of Burundi) FCS Fragile and conflict-affected situations FDI Foreign Direct Investment FNL Forces Nationales -

Burundi: T Prospects for Peace • BURUNDI: PROSPECTS for PEACE an MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT an MRG INTERNATIONAL

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R Burundi: T Prospects for Peace • BURUNDI: PROSPECTS FOR PEACE AN MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT AN MRG INTERNATIONAL BY FILIP REYNTJENS BURUNDI: Acknowledgements PROSPECTS FOR PEACE Minority Rights Group International (MRG) gratefully acknowledges the support of Trócaire and all the orga- Internally displaced © Minority Rights Group 2000 nizations and individuals who gave financial and other people. Child looking All rights reserved assistance for this Report. after his younger Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- sibling. commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- This Report has been commissioned and is published by GIACOMO PIROZZI/PANOS PICTURES mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the For further information please contact MRG. issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. author do not necessarily represent, in every detail and in ISBN 1 897 693 53 2 all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. ISSN 0305 6252 Published November 2000 MRG is grateful to all the staff and independent expert Typeset by Texture readers who contributed to this Report, in particular Kat- Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. rina Payne (Commissioning Editor) and Sophie Rich- mond (Reports Editor). THE AUTHOR Burundi: FILIP REYNTJENS teaches African Law and Politics at A specialist on the Great Lakes Region, Professor Reynt- the universities of Antwerp and Brussels. -

Integrated Regional Information Network (IRIN): Burundi

U.N. Department of Humanitarian Affairs Integrated Regional Information Network (IRIN) Burundi Sommaire / Contents BURUNDI HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT No. 4...............................................................5 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 26 July 1996 (96.7.26)..................................................9 Burundi-Canada: Canada Supports Arusha Declaration 96.8.8..............................................................11 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 14 August 1996 96.8.14..............................................13 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 15 August 1996 96.8.15..............................................15 Burundi: Statement by the US Catholic Conference and CRS 96.8.14...................................................17 Burundi: Regional Foreign Ministers Meeting Press Release 96.8.16....................................................19 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 16 August 1996 96.8.16..............................................21 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 20 August 1996 96.8.20..............................................23 Burundi: IRIN Daily Summary of Main Events 21 August 1996 96.08.21.............................................25 Burundi: Notes from Burundi Policy Forum meeting 96.8.23..............................................................27 Burundi: IRIN Summary of Main Events for 23 August 1996 96.08.23................................................30 Burundi: Amnesty International News Service 96.8.23.......................................................................32 -

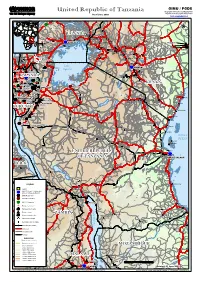

United Republic of Tanzania Geographic Information and Mapping Unit Population and Geographic Data Section As of June 2003 Email : [email protected]

GIMU / PGDS United Republic of Tanzania Geographic Information and Mapping Unit Population and Geographic Data Section As of June 2003 Email : [email protected] Soroti Masindi ))) ))) Bunia ))) HoimaHoima CCCCC CCOpiOpi !!! !! !!! !! !!! !! Mbale 55 !! 5555 55 Kitale !! 5555 Fort Portal UGANDAUGANDA !! CC !! Tororo !! ))) ))) !! ))) Bungoma !! !! Jinja CCCCCSwesweSweswe ))) Isiolo Tanzania_Atlas_A3PC.WOR CC ))) CC ))) KAMPALAKAMPALA ))) Kakamega DagahaleyDagahaley ))) Butembo !! ))) !! Entebbe Kisumu ))) Thomsons Falls!! Nanyuki IfoIfoIfo KakoniKakoni ))) !! ))) ))) ))) HagaderaHagadera ))) Lubero Londiani ))) DadaabDadaab Kabatoro ))) Molo ))) !! Nakuru ))) Bingi Elburgon !! Nyeri Gilgil ))) !! Embu CC))) MbararaMbarara Kinyasano CCMbararaMbarara !! Kisii ))) Naivasha ))) Fort Hall ))) )))) Nyakibale CCSettlementSettlement ))) CCCKifunzoKifunzo Makiro ))) Rutshuru ))) Thika ))) Kabale ))) ))) Lake ))) ))) Bukoba NAIROBINAIROBI Kikungiri Victoria ))) ))) ))) ))) MwisaMwisa Athi River !! GisenyiGisenyi ))) MwisaMwisa !! ))) ByumbaByumba Machakos yy!!))) Goma ))) Kajiado RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA ))) RWANDARWANDA Magadi ))) KIGALIKIGALI KibuyeKibuye ))) KibungoKibungo ))) KibungoKibungo KENYAKENYA ))) KENYAKENYA ))) KENYAKENYA ))) KENYAKENYA ))) KENYAKENYA ))) GikongoroGikongoro NgaraNgara))) ))) NgaraNgara ))) !! ))) LukoleLukole A&BA&B MwanzaMwanza !! )))LukoleLukole A&BA&B MuganoMugano ))) )))MbubaMbuba SongoreSongore ))) ))) Ngozi ))) MuyingaMuyinga ))) Nyaruonga -

Transaction Costs and Smallholder Farmers' Participation in Banana

Center of Evaluation for Global Action Working Paper Series Agriculture for Development Paper No. AfD-0909 Issued in July 2009 Transaction Costs and Smallholder Farmers’ Participation in Banana Markets in the Great Lakes Region John Jagwe Emily Ouma Charles Machethe University of Pretoria International Institute of Tropical Agriculture This paper is posted at the eScholarship Repository, University of California. http://repositories.cdlib.org/cega/afd Copyright © 2009 by the author(s). Series Description: The CEGA AfD Working Paper series contains papers presented at the May 2009 Conference on “Agriculture for Development in Sub-Saharan Africa,” sponsored jointly by the African Economic Research Consortium (AERC) and CEGA. Recommended Citation: Jagwe, John; Ouma, Emily; Machethe, Charles. (2009) Transaction Costs and Smallholder Farmers’ Participation in Banana Markets in the Great Lakes Region. CEGA Working Paper Series No. AfD-0909. Center of Evaluation for Global Action. University of California, Berkeley. Transaction Costs and Smallholder Farmers’ Participation in Banana Markets in the Great Lakes Region John Jagwe1, 2, Emily Ouma2, Charles Machethe1 1Department of Agricultural Economics, Extension and Rural Development, University of Pretoria (LEVLO, 002, Pretoria, South Africa); 2International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, Burundi, c/o IRAZ, B.P. 91 Gitega Keywords: smallholder farmers, market participation, transaction costs, bananas Abstract. This article analyses the determinants of the discrete decision of a household on whether to participate in banana markets using the FIML bivariate probit method. The continuous decision on how much to sell or buy is analyzed by establishing the supply and demand functions while accounting for the selectivity bias. Results indicate that buying and selling decisions are not statistically independent and the random disturbances in the buying and selling decisions are affected in opposite directions by random shocks. -

Download the PDF File

The following are just some guidelines and recommendations for Tourism in Burundi. I. Travel Frequently-Asked-Questions What to bring? Mosquito repellent, medications, first-aid kit. Travel documents? Passport and visa required. How to get there? No direct flights from U.S.; connections through Brussels, London, Rome, Paris, Addis Abbas, Nairobi, Kampala, and Kigali on the following carriers: Ethiopian Airlines, Kenya Airways, and Air Burundi. Customs? No currency restrictions. How to get around? Buses, vans (cars) and trucks to Kigali, Democratic Republic of Congo and Dar-es-Salaam Driver's license? International Driving Permit. Language? Kirundi, French, Swahili Food and drink? Lunch and dinner are main meals. Sauces (fish, chicken, beef, etc.) with beans, vegetables, potatoes, banana, rice and fufu. Water, juices, beer, wine, liquor, and soft drinks. Tipping? Required but no set up percentage. Customer uses his/her own judgment Weather? Mild temperatures during the day, cooler evenings. Clothes? Lightweight clothes. Sweater in the evening. Electricity? 220 volts. Plugs have 2 round prongs as in Europe. Money? BuFrs 1100=US$1; credit cards rarely accepted, but cash may be withdrawn with card at certain banks. Travellers' checks cashed at local banks. Phone service? International calls from the "Office National des Telecommunications" (0NATEL), hotels and phone centers. Post Office and mail? Office Nationale de la Poste. BuFrs 600/letter. Business hours? Offices: 7:30-12:00, 2:00-5:00 PM, Monday through Friday Banks: 7:30 AM - 12:00 PM, 2:00-5:00 PM, Monday through Friday (some banks open Saturday morning) Shopping hours: 7:30 AM - 7:00 PM, Monday through Saturday Safety? If you want to know the security situation prevailing in Burundi, contact your embassy in Bujumbura or the United Nations representations in Bujumbura. -

An Estimated Dynamic Model of African Agricultural Storage and Trade

High Trade Costs and Their Consequences: An Estimated Dynamic Model of African Agricultural Storage and Trade Obie Porteous Online Appendix A1 Data: Market Selection Table A1, which begins on the next page, includes two lists of markets by country and town population (in thousands). Population data is from the most recent available national censuses as reported in various online databases (e.g. citypopulation.de) and should be taken as approximate as census years vary by country. The \ideal" list starts with the 178 towns with a population of at least 100,000 that are at least 200 kilometers apart1 (plain font). When two towns of over 100,000 population are closer than 200 kilometers the larger is chosen. An additional 85 towns (italics) on this list are either located at important transport hubs (road junctions or ports) or are additional major towns in countries with high initial population-to-market ratios. The \actual" list is my final network of 230 markets. This includes 218 of the 263 markets on my ideal list for which I was able to obtain price data (plain font) as well as an additional 12 markets with price data which are located close to 12 of the missing markets and which I therefore use as substitutes (italics). Table A2, which follows table A1, shows the population-to-market ratios by country for the two sets of markets. In the ideal list of markets, only Nigeria and Ethiopia | the two most populous countries | have population-to-market ratios above 4 million. In the final network, the three countries with more than two missing markets (Angola, Cameroon, and Uganda) are the only ones besides Nigeria and Ethiopia that are significantly above this threshold. -

Truth Commissions and Reparations: a Framework for Post- Conflict Justice in Argentina, Chile Guatemala, and Peru

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Honors Theses (PPE) Philosophy, Politics and Economics 5-2021 Truth Commissions and Reparations: A Framework for Post- Conflict Justice in Argentina, Chile Guatemala, and Peru Anthony Chen Student Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ppe_honors Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Comparative Politics Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, International Law Commons, International Relations Commons, Latin American History Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, Law and Philosophy Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Models and Methods Commons, Other Political Science Commons, Political History Commons, and the Political Theory Commons Chen, Anthony, "Truth Commissions and Reparations: A Framework for Post-Conflict Justice in Argentina, Chile Guatemala, and Peru" (2021). Honors Theses (PPE). Paper 43. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/ppe_honors/43 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Truth Commissions and Reparations: A Framework for Post-Conflict Justice in Argentina, Chile Guatemala, and Peru Abstract This paper seeks to gauge the effectiveness of truth commissions and their links to creating material reparations programs through two central questions. First, are truth commissions an effective way to achieve justice after periods of conflict marked by mass or systemic human rights abuses by the government or guerilla groups? Second, do truth commissions provide a pathway to material reparations programs for victims of these abuses? It will outline the conceptual basis behind truth commissions, material reparations, and transitional justice. It will then engage in case studies and a comparative analysis of truth commissions and material reparations programs in four countries: Argentina, Chile, Guatemala, and Peru. -

Burundian League of Human Rights "Iteka"

BURUNDIAN LEAGUE OF HUMAN RIGHTS "ITEKA" Approved by Ministerial Order n ° 530/0273 of 10 November 1994 revising Order No. 550 /029 of 6 February 1991 "Is a member of the Inter-African Union of Human and Peoples' Rights (UIDH), is an affiliate member of the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), has observer status to the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights and has special consultative status to the ECOSOC" Monthly report « ITEKA N’IJAMBO » of the Burundian League of Human Rights "ITEKA" June 2017 In memory of Madam Marie Claudette Kwizera, Treasurer of Iteka, reported missing since December 10 2015. From December 2015 to 30 June 2017, Iteka has documented at least 437 cases of enforced disappearances. Page 1 of 33 CONTENTS PAGES 0. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………….………………5 I.ALLEGATIONS AND VIOLATIONS OF HUMAN RIGHTS……………………………………………………7 I.1. ALLEGATIONS OF VIOLATIONS OF THE RIGHT TO LIFE…………………………………………….7 I.1.1. PERSONS KILLED BY IMBONERAKURE, SNR AGENTS, POLICEMEN AND/OR SOLDIERS.7 I.1.2. PERSONS KILLED BY UNIDENTIFIED PEOPLE………………………………………………………8 I.1.3. CORPSES FOUND IN RIVER, BUSH AND/OR THE STREET…………………………………………10 I.1.4. PERSONS KILLED FOLLOWING MOB JUSTICE AND/OR SETTLING ACCOUNTS ……………11 I.2. PERSONS ABDUCTED AND REPORTED MISSING……………………………………………………..13 I.3. PERSONS TORTURED BY IMBONERAKURE, POLICEMEN AND/OR SOLDIERS………………..15 I.4. PERSONS ARRESTED BY IMBONERAKURE, SNR AGENTS, POLICEMEN AND/OR SOLDIERS18 II. CASES OF GENDER BASED VIOLENCE……………………………………………………………………24 III. INTIMIDATION BY CNDD-FDD -

Burundi Food Security Monitoring Early Warning System SAP/SSA Bulletin N° 104/July 2011 Publication/August 2011

Burundi Food Security Monitoring Early Warning System SAP/SSA Bulletin n° 104/July 2011 Publication/August 2011 Map of emergency assistance needs in agriculture ► Increase of theft of crops and in households is for season 2012A N concerning as it is likely to bear a negative impact on food stocks and reserves from Season 2011B crops; Bugabira Busoni Giteranyi ► Whereas normally it is dry season, torrential rains with Kirundo Bwambarangwe Ntega Kirundo Rwanda hail recorded in some locations during the first half of June Gitobe Mugina Butihinda Mabayi Marangara Vumbi have caused agricultural losses and disturbed maturing Gashoho Nyamurenza Muyinga Mwumba bean crops....; Rugombo Cibitoke Muyinga Busiga Kiremba Gasorwe Murwi Kabarore Ngozi Bukinanyana Gashikanwa Kayanza Ngozi Tangara Muruta Gahombo Gitaramuka Buganda Buhinyuza Gatara Ruhororo Musigati Kayanza Kigamba ►Despite improvement of production in Season 2011A (3% Bubanza Muhanga Buhiga Bubanza Maton go Bugenyuzi Mwakiro Mishiha Gihogazi increase comparing to 2010B), the food deficits remain high Rango Mutaho Cankuzo Mpanda Karuzi Gihanga Buk eye Mutumba Rugazi Cankuzo for the second semester of the year, notably because the Mbuye Gisagara Muramvya Bugendana Nyabikere Mutimbuzi Shombo Bweru Muramvya Cendajuru imports that could supplement those production deficits are Buja Rutegama Isale Kiganda Giheta Ndava Butezi Mairie Mugongomanga reduced by the sub-regional food crisis. … ; Gisuru Kanyosha Gitega Ruyigi Buja Rusaka Nyabihanga Nyabiraba Gitega Ruyigi MutamRbuural Mwaro Kabezi Kayokwe ► Households victims of various climate disturbances Makebuko Mukike Gisozi Nyanrusange Butaganzwa Itaba Kinyinya Muhuta Bisoro Gishubi recorded in season 2011B and those with low resilience Nyabitsinda Mugamba Bugarama Ryansoro Bukirasazi capacity have not taken advantage of conducive conditions Matana Buraza Musongati Giharo D for a good production of Season 2011B and so remain Burambi R Mpinga-Kayove a Buyengero i Songa C Rutovu Rutana n Rutana a vulnerable to food insecurity. -

Economic and Social Council

UNITED NATIONS E Distr. Economic and Social GENERAL Council E/CN.4/1997/12/Add.1 7 March 1997 ENGLISH Original: FRENCH COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Fiftythird session Item 3 of the provisional agenda ORGANIZATION OF THE WORK OF THE SESSION Second report on the human rights situation in Burundi submitted by the Special Rapporteur, Mr. Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro, in accordance with Commission resolution 1996/1 Addendum Introduction 1. This document is an addendum to the second report by the Special Rapporteur on the human rights situation in Burundi to the Commission on Human Rights at its fiftythird session. 2. Section A of this addendum contains a number of observations by the Special Rapporteur on the most recent developments in the crisis in Burundi and section B a list of the most significant allegations made to him concerning violations of the right to life and to physical integrity during the past year. A. Observations on the most recent developments in the crisis in Burundi 3. The serious violations of the right to life and to physical integrity listed in this addendum are closely linked to the further developments in the crisis in Burundi caused by the interruption of the transition to democracy following the assassination of President Ndadaye on 21 October 1993, the acts of genocide perpetrated against the Tutsis and the subsequent massacres of Hutus. Nevertheless, the current situation in Burundi and its influence on the human rights situation are closely linked to the resurgence of rebel movements in eastern Zaire and to the return of Burundi and Rwandan refugees to their countries of origin.