Charting a Future for Peacekeeping in the Democratic Republic of Congo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNHCR Republic of Congo Fact Sheet

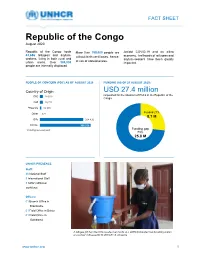

FACT SHEET Republic of the Congo August 2020 Republic of the Congo hosts More than 155,000 people are Amidst COVID-19 and an ailing 43,656 refugees and asylum- without birth certificates, hence, economy, livelihoods of refugees and seekers, living in both rural and asylum-seekers have been greatly at risk of statelessness. urban areas. Over 304,000 impacted. people are internally displaced PEOPLE OF CONCERN (POC) AS OF AUGUST 2020 FUNDING (AS OF 25 AUGUST 2020) Country of Origin USD 27.4 million requested for the situation of PoCs in the Republic of the DRC 20 810 Congo CAR 20,722 *Rwanda 10 565 Funded 27% Other 421 8.1 M IDPs 304 430 TOTAL: 356 926 * Including non-exempted Funding gap 73% 25.8 M UNHCR PRESENCE Staff: 46 National Staff 9 International Staff 8 IUNV (affiliated workforce) Offices: 01 Branch Office in Brazzaville 01 Field Office in Betou 01 Field Office in Gamboma A refugee girl from the DRC washes her hands at a UNHCR-installed handwashing station at a school in Brazzaville © UNHCR / S. Duysens www.unhcr.org 1 FACT SHEET > Republic of the Congo / August 2020 Working with Partners ■ Aligning with the Global Compact on Refugees (GCR), UNHCR in the Republic of the Congo (RoC) has diversified its partnership base to include five implementing partners, comprising local governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), as well as international NGOs. ■ The National Committee for Assistance to Refugees (CNAR), is UNHCR’s main governmental partner, covering general refugee issues, particularly Refugee Status Determination (RSD). Other specific governmental partners include the Ministry of Social and Humanitarian Affairs (MASAH), the Ministries of Justice and Interior (for judicial issues and policies on issues related to statelessness and civil status registration), and the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH). -

Ocha Drc Population Movements in Eastern Dr Congo October – December 2009

Population Movements in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo OCHA DRC POPULATION MOVEMENTS IN EASTERN DR CONGO OCTOBER – DECEMBER 2009 January 2010 1 Population Movements in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo 1. OVERVIEW The humanitarian situation and movement of populations in 2009 have been heavily influenced by military operations and the still prevailing insecurity in a number of areas in the eastern provinces. Between January 20 and February 25 2009, the Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo (FARDC) and the Rwanda Defence Forces (RDF) conducted joint operations (Umoja Wetu) in North Kivu against the Forces Démocratiques pour le Liberation du Rwanda (FDLR). In March 2009 a second military operation (Kimia II) was launched in North Kivu and South Kivu. Lubero, Rutshuru, Masisi and Walikale are the territories in North Kivu where major displacements have been reported since March 2009. In South Kivu the most affected areas are Kalehe, Uvira and Shabunda. The attacks carried out by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a Ugandan militia, in the Orientale province since September 2008 have spread from the Haut Uele district to the Bas Uele in 2009. The population is victim of atrocities and acts of extreme violence: killings, rapes, kidnapping and looting leading to population displacements in many locations of the districts. N. IDPs per Province 800 000 767 399 730 941 700 000 600 000 Haut Uele 500 000 Bas Uele Ituri North Kivu 400 000 South Kivu Equateur 239 210 Katanga 300 000 165 472 200 000 58 937 60 000 100 000 14 000 0 Note: Ituri, Haut Uele and Bas Uele are districts of the Orientale province During the reporting period (October ‐ December 2009) some displacements have been reported in the Katanga province where about 14.000 people have moved from South Kivu due to the military operations in the area bordering Katanga. -

Konrad English Layout - Vol 11.Indd 1 8/8/2012 11:04:58 AM Konrad Adenauer Stiftung

KONRAD ADENAUER STIFTUNG AFRICAN LAW STUDY LIBRARY Volume 11 Edited by Hartmut Hamann, Jean-Michel Kumbu & Yves-Junior Manzanza Lumingu Hartmut Hamann is a lawyer specialized in providing legal support for international projects between states and private companies, and in international arbitration proceedings. He is a professor at the Freie Universität Berlin, and at the Chemnitz University of Technology, where he teaches public international law and conflict resolution. His legal and academic activities often take him to Africa. ([email protected]) Jean-Michel Kumbu is a lecturer in employment law and economic legislation at Université de Kinshasa and other universities in Democratic Republic of Congo. He is a lawyer and focuses on business law. He is an expert in democratic governance by the United Nations Development Program in Kinshasa. Yves-Junior Manzanza Lumingu has a Bachelor of Law from the Université de Kinshasa where he worked as a research assistant to the Vice Dean. He was responsible for research within the faculty of law and was later nominated as an assistant at the Université de Kikwit (Bandundu / Democratic Republic of the Congo). Currently, he is pursuing his doctorate at the Julius-Maximilians- Universität Würzburg. His field of research covers the three areas "constitutional state – protection of private investment – worker protection". He is also interested in issues relating to the promotion of women’s and children’s rights. Konrad Published By: Adenauer Stiftung Rule of Law Program for Sub-Saharan Africa ©July 2012 AFRICAN LAW STUDY LIBRARY Vol 11 A Konrad English Layout - Vol 11.indd 1 8/8/2012 11:04:58 AM Konrad Adenauer Stiftung Office : Mbaruk Road, Hse, No. -

Burundi-SCD-Final-06212018.Pdf

Document of The World Bank Report No. 122549-BI Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF BURUNDI ADDRESSING FRAGILITY AND DEMOGRAPHIC CHALLENGES TO REDUCE POVERTY AND BOOST SUSTAINABLE GROWTH Public Disclosure Authorized SYSTEMATIC COUNTRY DIAGNOSTIC June 15, 2018 Public Disclosure Authorized International Development Association Country Department AFCW3 Africa Region International Finance Corporation (IFC) Sub-Saharan Africa Department Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) Sub-Saharan Africa Department Public Disclosure Authorized BURUNDI - GOVERNMENT FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective as of December 2016) Currency Unit = Burundi Franc (BIF) US$1.00 = BIF 1,677 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ACLED Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project AfDB African Development Bank BMM Burundi Musangati Mining CE Cereal Equivalent CFSVA Comprehensive Food Security and Vulnerability Assessment CNDD-FDD Conseil National Pour la Défense de la Démocratie-Forces pour la Défense de la Démocratie (National Council for the Defense of Democracy-Forces for the Defense of Democracy) CPI Consumer Price Index CPIA Country Policy and Institutional Assessment DHS Demographic and Health Survey EAC East African Community ECVMB Enquête sur les Conditions de Vie des Menages au Burundi (Survey on Household Living Conditions in Burundi) ENAB Enquête Nationale Agricole du Burundi (National Agricultural Survey of Burundi) FCS Fragile and conflict-affected situations FDI Foreign Direct Investment FNL Forces Nationales -

Reconstruction Under Fire: Case Studies and Further Analysis Of

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Reconstruction Under Fire Case Studies and Further Analysis of Civil Requirements A COMPANION VOLUME TO RECONSTRUCTION UNDER FIRE: UNIFYING CIVIL AND MILITARY COUNTERINSURGENCY Brooke Stearns Lawson, Terrence K. -

Executive Summary

Monthly Protection Monitoring Report – North Kivu September 2015 Executive Summary 2845 incidents have been recorded in September 2015. The number has decreased by 6,3% compared to August 2015 pendant, when 3037 incidents were reported. The territory Incidents per territory of Rutshuru has had the BENI 369 highest LUBERO 369 number of MASISI 639 incidents in NYIRAGONGO 133 September RUTSHURU 919 2015 WALIKALE 416 TOTAL 2845 Incidents per Incidents per alleged perpetrator category of victim Nombre des cas par type d’incident The majority of incidents in September 2015 were violations to the right of property and liberty PROTECTION MONITORING PMS Province du Nord Kivu 2 | UNHCR Protection Monitoring Nor th K i v u – Sept. Monthly Report PROTECTION MONITORING PMS Province du Nord Kivu I. Summary of main protection concerns Throughout September 2015, the PMS has registered 59,8% less internal displacement than in August 2015. This decrease can be justified by the relative calm perceived in significant displacement areas. On 17 September 2015, alleged NDC Cheka members pillaged Kalehe village to the Northeast of Bunyatenge and kidnapped around 30 people that were forced to transport the stolen goods to Mwanza and Mutiri, in Lubero territory. II. Protection context by territory MASISI The security situation in Masisi was characterised by clashes between FARDC and FDLR, between two different factions of FDDH (FDDH/Tuombe and FDDH/Mugwete) and between FARDC and APCLS. These conflicts have led to the massive displacement of the population from the areas affected by fighting followed by looting, killings and other violations. In Bibwe, around 400 families were displaced, among which 72 households are staying in a church and a school in Bibwe and around 330 families created a new site, accessible by car, around 2km from the Bibwe site. -

Of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO

Assessing the of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO REPORT 3/2019 Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2019 ISBN: 978-82-7002-346-2 Any views expressed in this publication are those of the author. Tey should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. Te text may not be re-published in part or in full without the permission of NUPI and the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: effectivepeaceops.net | www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 99 40 50 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 Assessing the Efectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC (MONUC-MONUSCO) Lead Author Dr Alexandra Novosseloff, International Peace Institute (IPI), New York and Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo Co-authors Dr Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Prof. Tomas Mandrup, Stellenbosch University, South Africa, and Royal Danish Defence College, Copenhagen Aaron Pangburn, Social Science Research Council (SSRC), New York Data Contributors Ryan Rappa and Paul von Chamier, Center on International Cooperation (CIC), New York University, New York EPON Series Editor Dr Cedric de Coning, NUPI External Reference Group Dr Tatiana Carayannis, SSRC, New York Lisa Sharland, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra Dr Charles Hunt, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, Australia Adam Day, Centre for Policy Research, UN University, New York Cover photo: UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti UN Photo/ Abel Kavanagh Contents Acknowledgements 5 Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 13 Te effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC across eight critical dimensions 14 Strategic and Operational Impact of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Constraints and Challenges of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Current Dilemmas 19 Introduction 21 Section 1. -

Addressing Root Causes of Conflict: a Case Study Of

Experience paper Addressing root causes of conflict: A case study of the International Security and Stabilization Support Strategy and the Patriotic Resistance Front of Ituri (FRPI) in Ituri Province, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo Oslo, May 2019 1 About the Author: Ingebjørg Finnbakk has been deployed by the Norwegian Resource Bank for Democracy and Human Rights (NORDEM) to the Stabilization Support Unit (SSU) in MONUSCO from August 2016 until February 2019. Together with SSU Headquarters and Congolese partners she has been a key actor in developing and implementing the ISSSS program in Ituri Province, leading to a joint MONUSCO and Government process and strategy aimed at demobilizing a 20-year-old armed group in Ituri, the Patriotic Resistance Front of Ituri (FRPI). The views expressed in this report are her own, and do not represent those of either the UN or the Norwegian Refugee Council/NORDEM. About NORDEM: The Norwegian Resource Bank for Democracy and Human Rights (NORDEM) is NORCAP’s civilian capacity provider specializing in human rights and support for democracy. NORDEM has supported the SSU with personnel since 2013, hence contribution significantly with staff through the various preparatory phases as well as during the implementation. Acknowledgements: Reaching the point of implementing ISSSS phase two programs has required a lot of analyses, planning and stakeholder engagement. The work presented in this report would not be possible without all the efforts of previous SSU staff under the leadership of Richard de La Falaise. The FRPI process would not have been possible without the support and visions from Francois van Lierde (deployed by NORDEM) and Frances Charles at SSU HQ level. -

Deforestation and Forest Degradation Activities in the DRC

E4838 V5 DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO MINISTRY FOR THE ENVIRONMENT, NATURE CONSERVATION AND TOURISM Public Disclosure Authorized STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT OF THE REDD+ PROCESS Public Disclosure Authorized BASELINE REPORT STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT OF THE REDD+ Public Disclosure Authorized PROCESS Public Disclosure Authorized October 2014 STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT OF THE REDD+ PROCESS in the DRC INDEX OF REPORTS Environmental Analysis Document Assessment of Risks and Challenges REDD+ National Strategy of the DRC Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment Report (SESA) Framework Document Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) O.P. 4.01, 4.04, 4.37 Policies and Sector Planning Documents Pest and Pesticide Cultural Heritage Indigenous Peoples Process Framework Management Management Planning Framework (FF) Resettlement Framework Framework (IPPF) O.P.4.12 Policy Framework (PPMF) (CHMF) O.P.4.10 (RPF) O.P.4.09 O.P 4.11 O.P. 4.12 Consultation Reports Survey Report Provincial Consultation Report National Consultation of June 2013 Report Reference and Analysis Documents REDD+ National Strategy Framework of the DRC Terms of Reference of the SESA October 2014 Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment SESA Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory Note ........................................................................................................................................ 9 1. Preface ............................................................................................................................................ -

Mai-Ndombe Province: a REDD+ Laboratory in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

RIGHTS AND RESOURCES INITIATIVE | MARCH 2018 Rights and Resources Initiative 2715 M Street NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20007 P : +1 202.470.3900 | F : +1 202.944.3315 www.rightsandresources.org About the Rights and Resources Initiative RRI is a global coalition consisting of 15 Partners, 7 Affiliated Networks, 14 International Fellows, and more than 150 collaborating international, regional, and community organizations dedicated to advancing the forestland and resource rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. RRI leverages the capacity and expertise of coalition members to promote secure local land and resource rights and catalyze progressive policy and market reforms. RRI is coordinated by the Rights and Resources Group, a non-profit organization based in Washington, DC. For more information, please visit www.rightsandresources.org. Partners Affiliated Networks Sponsors The views presented here are not necessarily shared by the agencies that have generously supported this work, or all of the Partners and Affiliated Networks of the RRI Coalition. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY 4.0. – 2 – Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Acronyms ............................................................................................................................................................. 5 Executive summary ........................................................................................................................................... -

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS for the DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20 BAS-UELE HAUT-UELE ITURI S O U T H S U D A N COUNTRYWIDE NORTH KIVU OCHA IMA World Health Samaritan’s Purse AIRD Internews CARE C.A.R. Samaritan’s Purse Samaritan’s Purse IMA World Health IOM UNHAS CAMEROON DCA ACTED WFP INSO Medair FHI 360 UNICEF Samaritan’s Purse Mercy Corps IMA World Health NRC NORD-UBANGI IMC UNICEF Gbadolite Oxfam ACTED INSO NORD-UBANGI Samaritan’s WFP WFP Gemena BAS-UELE Internews HAUT-UELE Purse ICRC Buta SCF IOM SUD-UBANGI SUD-UBANGI UNHAS MONGALA Isiro Tearfund IRC WFP Lisala ACF Medair UNHCR MONGALA ITURI U Bunia Mercy Corps Mercy Corps IMA World Health G A EQUATEUR Samaritan’s NRC EQUATEUR Kisangani N Purse WFP D WFPaa Oxfam Boende A REPUBLIC OF Mbandaka TSHOPO Samaritan’s ATLANTIC NORTH GABON THE CONGO TSHUAPA Purse TSHOPO KIVU Lake OCEAN Tearfund IMA World Health Goma Victoria Inongo WHH Samaritan’s Purse RWANDA Mercy Corps BURUNDI Samaritan’s Purse MAI-NDOMBE Kindu Bukavu Samaritan’s Purse PROGRAM KEY KINSHASA SOUTH MANIEMA SANKURU MANIEMA KIVU WFP USAID/BHA Non-Food Assistance* WFP ACTED USAID/BHA Food Assistance** SA ! A IMA World Health TA N Z A N I A Kinshasa SH State/PRM KIN KASAÏ Lusambo KWILU Oxfam Kenge TANGANYIKA Agriculture and Food Security KONGO CENTRAL Kananga ACTED CRS Cash Transfers For Food Matadi LOMAMI Kalemie KASAÏ- Kabinda WFP Concern Economic Recovery and Market Tshikapa ORIENTAL Systems KWANGO Mbuji T IMA World Health KWANGO Mayi TANGANYIKA a KASAÏ- n Food Vouchers g WFP a n IMC CENTRAL y i k -

A Life of Fear and Flight

A LIFE OF FEAR AND FLIGHT The Legacy of LRA Brutality in North-East Democratic Republic of the Congo We fled Gilima in 2009, as the LRA started attacking there. From there we fled to Bangadi, but we were confronted with the same problem, as the LRA was attacking us. We fled from there to Niangara. Because of insecurity we fled to Baga. In an attack there, two of my children were killed, and one was kidnapped. He is still gone. Two family members of my husband were killed. We then fled to Dungu, where we arrived in July 2010. On the way, we were abused too much by the soldiers. We were abused because the child of my brother does not understand Lingala, only Bazande. They were therefore claiming we were LRA spies! We had to pay too much for this. We lost most of our possessions. Once in Dungu, we were first sleeping under a tree. Then someone offered his hut. It was too small with all the kids, we slept with twelve in one hut. We then got another offer, to sleep in a house at a church. The house was, however, collapsing and the owner chased us. He did not want us there. We then heard that some displaced had started a camp, and that we could get a plot there. When we had settled there, it turned out we had settled outside of the borders of the camp, and we were forced to leave. All the time, we could not dig and we had no access to food.