DOCUNENT RESUME ED 127 638 CS 501 461 AUTHOR Harms, LS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2018 Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany William Peter Fitz University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Fitz, William Peter, "Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany" (2018). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 275. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/275 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REACTIONARY POSTMODERNISM? NEOLIBERALISM, MULTICULTURALISM, THE INTERNET, AND THE IDEOLOGY OF THE NEW FAR RIGHT IN GERMANY A Thesis Presented by William Peter Fitz to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In European Studies with Honors December 2018 Defense Date: December 4th, 2018 Thesis Committee: Alan E. Steinweis, Ph.D., Advisor Susanna Schrafstetter, Ph.D., Chairperson Adriana Borra, M.A. Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One: Neoliberalism and Xenophobia 17 Chapter Two: Multiculturalism and Cultural Identity 52 Chapter Three: The Philosophy of the New Right 84 Chapter Four: The Internet and Meme Warfare 116 Conclusion 149 Bibliography 166 1 “Perhaps one will view the rise of the Alternative for Germany in the foreseeable future as inevitable, as a portent for major changes, one that is as necessary as it was predictable. -

Queer Theory, Ethno/Musicology, and the Disorientation of the Field

Queer Theory, Ethno/Musicology, and the Disorientation of the Field Steven Moon We spend significant time and space in our academic lives positioning ourselves: within the theory of the field, in regard to the institution, within networks of interlocutors, scholars, performers, and so on. We are likewise trained to critique those positions, to identify modes of power in their myriad manifestations, and to work towards more equitable methods and theory. That is, we constantly are subject to attempts of disciplinary orienta- tion, and constantly negotiate forms of re-orientation. Sara Ahmed reminds us that we might ask not only how we are oriented within our discipline, but also about 1) how the discipline itself is oriented, and 2) how orien- tation within sexuality shapes how our bodies extend into space (2006). This space—from disciplinary space, to performance space, to the space of fieldwork and the archive—is a boundless environment cut by the trails of the constant reorientation of those before us. But our options are more than the dichotomy between “be oriented” and “re-orient oneself.” In this essay, I examine the development of the ethno/musicologies’ (queer) theoretical borrowings from anthropology, sociology, and literary/cultural studies in order to historicize the contemporary queer moment both fields are expe- riencing and demonstrate the ways in which it might dis-orient the field. I trace the histories of this queer-ing trend by beginning with early concep- tualizations of the ethno/musicological projects, scientism, and quantita- tive methods. This is in relation to the anthropological method of ethno- cartography in order to understand the historical difficulties in creating a queer qualitative field, as opposed to those based in hermeneutics. -

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds an End to Antisemitism!

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds An End to Antisemitism! Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman Volume 5 Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman ISBN 978-3-11-058243-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-067196-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-067203-9 DOI https://10.1515/9783110671964 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number: 2021931477 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, Lawrence H. Schiffman, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com Cover image: Illustration by Tayler Culligan (https://dribbble.com/taylerculligan). With friendly permission of Chicago Booth Review. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com TableofContents Preface and Acknowledgements IX LisaJacobs, Armin Lange, and Kerstin Mayerhofer Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds: Introduction 1 Confronting Antisemitism through Critical Reflection/Approaches -

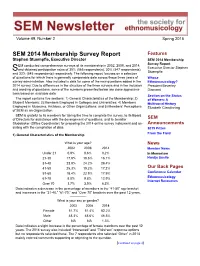

SEM 2014 Membership Survey Report Features Stephen Stuempfle, Executive Director SEM 2014 Membership

Volume 49, Number 2 Spring 2015 SEM 2014 Membership Survey Report Features Stephen Stuempfle, Executive Director SEM 2014 Membership EM conducted comprehensive surveys of its membership in 2002, 2008, and 2014, Survey Report Executive Director Stephen and obtained participation rates of 35% (565 respondents), 30% (547 respondents), S Stuempfle and 32% (545 respondents) respectively. The following report focuses on a selection of questions for which there is generally comparable data across these three years of Whose survey administration. Also included is data for some of the new questions added in the Ethnomusicology? 2014 survey. Due to differences in the structure of the three surveys and in the inclusion President Beverley and wording of questions, some of the numbers presented below are close approxima- Diamond tions based on available data. Section on the Status The report contains five sections: 1) General Characteristics of the Membership; 2) of Women: A Student Members; 3) Members Employed in Colleges and Universities; 4) Members Multivocal History Employed in Museums, Archives, or Other Organizations; and 5) Members’ Perceptions Elizabeth Clendinning of SEM as an Organization. SEM is grateful to its members for taking the time to complete the survey, to its Board of Directors for assistance with the development of questions, and to Jennifer SEM Studebaker (Office Coordinator) for preparing the 2014 online survey instrument and as- Announcements sisting with the compilation of data. 2015 Prizes From the Field 1) General Characteristics of the Membership What is your age? News 2002 2008 2014 Member News Under 21 0.9% 0.6% 0.2% In Memoriam 21-30 17.9% 19.6% 16.1% Hardja Susilo 31-40 23.9% 24.2% 29.4% 41-50 25.3% 19.2% 17.2% Our Back Pages 51-60 18.4% 22.9% 17.9% Conference Calendar 61-70 8.0% 9.8% 12.9% Ethnomusicology Internet Resources Over 70 3.7% 3.9% 6.3% Data indicates a decrease in the percentage of members in the “41-50” age bracket and increases in the “31-40,” “61-70,” and “Over 70” brackets over the past 12 years. -

Volume 43, No. 2-3, June-September 2015

EAST EUROPEAN QUARTERLY Volume 43 June-September 2015 No. 2-3 Articles Glenn Diesen Inter-Democratic Security Institutions and the Security Dilemma: A Neoclassical Realist Model of the EU and NATO after the End of the Soviet Union 137 Yannis Sygkelos Nationalism versus European Integration: The Case of ATAKA 163 Piro Rexepi Mainstreaming Islamophobia: The Politics of European Enlargement and the Balkan Crime-Terror Nexus 189 Direct Democracy Notes Dragomir Stoyanov: The 2014 Electoral Code Initiative in Bulgaria 217 Alenka Krasovec: The 2014 Referendum in Slovenia 225 Maciej Hartliński: The 2015 Referendum in Poland 235 East European Quarterly Department of Political Science Central European University, Budapest June-September 2015 EDITOR: Sergiu Gherghina, Goethe University Frankfurt DIRECT DEMOCRACY NOTES EDITOR: Peter Spac, Masaryk University Brno BOOK REVIEWS EDITOR: Theresa Gessler, European University Institute Florence EDITORIAL BOARD: Nicholas Aylott, Södertörn University Stockholm Andras Bozoki, Central European University Budapest Fernando Casal Bertoa, University of Nottingham Mihail Chiru, Median Research Center Bucharest Danica Fink-Hafner, University of Ljubljana Petra Guasti, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz Henry Hale, George Washington University Tim Haughton, University of Birmingham John T. Ishiyama, University of North Texas Petr Kopecky, Leiden University Algis Krupavicius, Kaunas University of Technology Levente Littvay, Central European University Budapest Grigore Pop-Eleches, Princeton University Robert Sata, -

University of Hawai'i System

University of Hawai‘i System Native Hawaiian Student Programs Directory 2011 Initiative of the Pūkoʻa Council He Pūkoʻa e kani ai ka ʻĀina ―A grain of coral eventually grows into land.‖ 1 Table of Contents Purpose and Function of the Pūkoʻa Council 3 University of Hawai‘i System Scholarship Opportunities 4 Hawaiʻi Island Hawaiʻi Community College 7 University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo 8 University of Hawaiʻi —West Hawaiʻi Center 14 Kauaʻi Island Kauaʻi Community College 15 Lānaʻi Island Lānaʻi High & Elementary School 17 Maui Island University of Hawai‗i Maui College 18 Molokaʻi Island Molokaʻi Educational Center 21 Oʻahu Island Honolulu Community College 21 Kapiʻolani Community College 24 Leeward Community College 27 Windward Community College 29 University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa 31 University of Hawaiʻi West Oʻahu 44 2 Purpose and Function of the Pūkoʻa Council The purpose of the Pūkoʻa Council of the University of Hawaiʻi is to provide a formal, independent voice and organization through which the Native Hawaiian faculty, administrators, and students of the University of Hawaiʻi system can participate in the development and interpretation of system-wide policy and practice as it relates to Native Hawaiian programs, activities, initiatives, and issues. Specifically, the Council will: 1. Provide advice and information to the President of the University, on issues that have particular relevance for Native Hawaiians and for Native Hawaiian culture, language, and history. 2. Work with the system and campus administration to position the University as one of the world's foremost indigenous-serving universities. 3. Promote the access and success of Native Hawaiian students in undergraduate, graduate and professional programs, and the increase in representation of Native Hawaiians in all facets of the University. -

Filipino Americans and Polyculturalism in Seattle, Wa

FILIPINO AMERICANS AND POLYCULTURALISM IN SEATTLE, WA THROUGH HIP HOP AND SPOKEN WORD By STEPHEN ALAN BISCHOFF A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN AMERICAN STUDIES WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Department of American Studies DECEMBER 2008 To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the thesis of STEPHEN ALAN BISCHOFF find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. _____________________________________ Chair, Dr. John Streamas _____________________________________ Dr. Rory Ong _____________________________________ Dr. T.V. Reed ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Since I joined the American Studies Graduate Program, there has been a host of faculty that has really helped me to learn what it takes to be in this field. The one professor that has really guided my development has been Dr. John Streamas. By connecting me to different resources and his challenging the confines of higher education so that it can improve, he has been an inspiration to finish this work. It is also important that I mention the help that other faculty members have given me. I appreciate the assistance I received anytime that I needed it from Dr. T.V. Reed and Dr. Rory Ong. A person that has kept me on point with deadlines and requirements has been Jean Wiegand with the American Studies Department. She gave many reminders and explained answers to my questions often more than once. Debbie Brudie and Rose Smetana assisted me as well in times of need in the Comparative Ethnic Studies office. My cohort over the years in the American Studies program have developed my thinking and inspired me with their own insight and work. -

The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: a Multilevel Process Theory1

The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: A Multilevel Process Theory1 Andreas Wimmer University of California, Los Angeles Primordialist and constructivist authors have debated the nature of ethnicity “as such” and therefore failed to explain why its charac- teristics vary so dramatically across cases, displaying different de- grees of social closure, political salience, cultural distinctiveness, and historical stability. The author introduces a multilevel process theory to understand how these characteristics are generated and trans- formed over time. The theory assumes that ethnic boundaries are the outcome of the classificatory struggles and negotiations between actors situated in a social field. Three characteristics of a field—the institutional order, distribution of power, and political networks— determine which actors will adopt which strategy of ethnic boundary making. The author then discusses the conditions under which these negotiations will lead to a shared understanding of the location and meaning of boundaries. The nature of this consensus explains the particular characteristics of an ethnic boundary. A final section iden- tifies endogenous and exogenous mechanisms of change. TOWARD A COMPARATIVE SOCIOLOGY OF ETHNIC BOUNDARIES Beyond Constructivism The comparative study of ethnicity rests firmly on the ground established by Fredrik Barth (1969b) in his well-known introduction to a collection 1 Various versions of this article were presented at UCLA’s Department of Sociology, the Institute for Migration Research and Intercultural Studies of the University of Osnabru¨ ck, Harvard’s Center for European Studies, the Center for Comparative Re- search of Yale University, the Association for the Study of Ethnicity at the London School of Economics, the Center for Ethnicity and Citizenship of the University of Bristol, the Department of Political Science and International Relations of University College Dublin, and the Department of Sociology of the University of Go¨ttingen. -

AS-3438-20/AA Recommended Core Competencies for Ethnic Studies

ACADEMIC SENATE OF THE CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY AS-3438-20/AA September 17-18, 2020 RECOMMENDED CORE COMPETENCIES FOR ETHNIC STUDIES: RESPONSE TO CALIFORNIA EDUCATION CODE 89032C RESOLVED: That the ASCSU acknowledge that the California Education Code 89032c requires “The California State University shall collaborate with the California State University Council on Ethnic Studies and the Academic Senate of the California State University to develop core competencies* to be achieved by students who complete an ethnic studies course…”, and be it further RESOLVED: That the ASCSU recommend the adoption of the following five core ethnic studies competencies iteratively developed by the CSU Council on Ethnic Studies and the ASCSU: • analyze and articulate concepts of ethnic studies, including but not limited to race and ethnicity, racialization, equity, ethno-centrism, eurocentrism, white supremacy, self-determination, liberation, decolonization and anti-racism. • apply theory to describe critical events in the histories, cultures, and intellectual traditions, with special focus on the lived- experiences and social struggles of one or more of the following four historically defined racialized core groups: Native Americans, African Americans, Latina/o Americans, and/or Asian Americans, and emphasizing agency and group-affirmation. • critically discuss the intersection of race and ethnicity with other forms of difference affected by hierarchy and oppression, such as class, gender, sexuality, religion, spirituality, national origin, immigration status, ability, and/or age. • describe how struggle, resistance, social justice, solidarity, and liberation as experienced by communities of color are relevant to current issues. • demonstrate active engagement with anti-racist issues, practices and movements to build a diverse, just, and equitable society beyond the classroom. -

Ethnic Studies Review (ESR) Is the Journal of the National Association for Ethnic Studies (NAES)

The National Association for Ethnic Studies Ethnic Studies Review (ESR) is the journal of the National Association for Ethnic Studies (NAES). ESR is a multi-disciplinary international journal devoted to the study of ethnicity, ethnic groups and their cultures, and intergroup relations. NAES has as its basic purpose the promotion of activities and scholarship in the field of Ethnic Studies. The Association is open to any person or institution and serves as a forum for its members in promoting research, study, and curriculum as well as producing publications of interest in the field. NAES sponsors an annual spring conference. General Editor: Faythe E. Turner, Greenfield Community College Book Review Editor: Jonathan A. Majak, University of Wisconsin-Lacrosse Editorial Advisory Board Edna Acosta-Belen Rhett S. Jones University at Albany, SUNY Brown University Jorge A. Bustamante Paul Lauter El Colegio de la Frontera Norte (Mexico) Trinity College Duane W. Champagne Robert L. Perry University of California, Los Angeles Eastern Michigan University Laura Coltelli Otis L. Scott Universita de Pisa (Italy) California State University Sacramento Russell Endo Alan J. Spector University of Colorado Purdue University, Calumet David M. Gradwohl K. Victor Ujimoto Iowa State University University of Guelph (Canada) Maria Herrera-Sobek John C. Walter University of California, Irvine University of Washington Evelyn Hu-DeHart Bernard Young University of Colorado, Boulder Arizona State University Designed by Eileen Claveloux Ethnic Studies Review (ESR) is published by the National Associaton for Ethnic Studies for its individual members and subscribing libraries and institutions. NAES is a member of the Council of Editors of Learned Journals. -

We Are Sweden Democrats Because We Care for Others: Exploring Racisms in the Swedish Extreme Right

We are Sweden Democrats because we care for others: Exploring racisms in the Swedish extreme right Diana Mulinari and Anders Neergaard Linköping University Post Print N.B.: When citing this work, cite the original article. Original Publication: Diana Mulinari and Anders Neergaard, We are Sweden Democrats because we care for others: Exploring racisms in the Swedish extreme right, 2014, The European Journal of Women's Studies, (21), 1, 43-56. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1350506813510423 Copyright: SAGE Publications (UK and US) http://www.uk.sagepub.com/home.nav Postprint available at: Linköping University Electronic Press http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-105759 Introduction During the last decades there has been an upsurge in research on xenophobic populist parties mirroring the political successes of these parties in Western Europe and to some extent in Eastern Europe. In the Swedish context, in a period of neoliberal restructuring of the welfare state, not only have issues of ‘race’, citizenship and belonging been important elements of the public debate, but these issues have unfolded in parallel with the presence of a neo-Nazi social movement and the emergence of two new parliamentary parties – New Democracy from 1991 to 1994 and Sweden Democrats (SD) from 2010 – in which cultural racism has been central (Deland and Westin, 2007). Mainstream research has especially focused on the xenophobic content and how to relate these parties to the wider research on party politics in Western liberal democracies. While there have been some studies emphasising the fact that women to a lesser degree than men vote and participate in these parties, there are still very few studies analysing the worldview of women active in these parties, and the role of gender as metaphor, identity and as policy within these parties. -

Education Access Annual Report for 2016 Introduction

Education Access Annual Report for 2016 Introduction The following report is an overview of the Educational Access (EA) activities for the calendar year 2016. This report was compiled by the Hawaii Educational Networking Consortium (HENC) as a condition of the Educational Access agreement between ‘Olelo, Community Media and HENC. HENC is an informal consortium of the Hawaii State Dept. of Education (HDOE), the University of Hawaii (UH) and the Hawaii Association of Independent Schools (HAIS) formed in 1999 to jointly manage the formal institutional education access component of the programming that is funded by the cable franchise fees provided by Oceanic Cable and Hawaiian Telecom. This report is divided into four major sections that include: Section 1.0 - The Channels and their Programming Page 1 Section 2.0 - The 2016 Awards Page 2 Section 3.0 - Funding and Report Summary Page 8 Section 4.0 - Appendices Page 10 Section 1.0.0 - The Channels and their Programming Section 1.1.1 - EA Programming There are two Educational Access channels on Oahu known as UHTV and TEACH. On Oceanic Cable these channels can be found as digital channels 355 and 356 respectively (QAM channels 46.55 and 46.56). On Hawaiian Telecom TV the TEACH channel is 356 and the UHTV is 355. The programming reports for these two channels during 2016 can be found in Appendix 1 and 2 of this report. Programming Total Hours of Hours of Locally Hours of Repeat Hours by Type Programming Produced Programming Programming by Channel Year 2016 2016 2016 Channel 355 -- UHTV University of Hawaii 8,779 2,430 3,970 Channel 356 -- TEACH HDOE/Video Technology 8,120 3,110 4,060 Group EA Channels Total 16,899 5,540 8,030 In addition, during 2016 the UHTV Video On Demand (VOD) Channel on Oceanic Cable continued to be made available to Oceanic subscribers.