Competition for Railway Markets: the Case of Baden-Württemberg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zugbildungen Deutsche Reichsbahn, Ep. III/IV

Deutsche Reichsbahn, Ep. III/IV Zugbildungen Eilzug der 1950er Jahre: Eilzüge verkehrten über mittelgroße Entfernungen (meist zwischen zwei Ballungsräumen) und hielten nur in den wichtigeren Bahnhöfen. (Art. 02100 – 01563 – 13160) Personenzug Nahverkehr: Typischer Nebenbahnpersonenzug der 1980er Jahre. (Art. 04586 – 01561) D-Zug der 1960er Jahre. (Art. 02145 – 13896 – 16920 – 16900 – 16970 – 16940) Nahgüterzug: Die V 36 übernahm teilweise auch den leichten Streckendienst. (Art. 04630 – 13421 – 14125 – 01586 – 15611) D-Zug Mitte Epoche IV: Kombinierter Zug mit Reisezugwagen der frühen Ep. IV (schwarze Längsträger) und Speisewagen der späten Epoche IV. (Art. 02450 – 01570 – 16750 – 16340) Militärtransport der NVA (Art. 02673 – 01592 – 01593) Städteexpress für den hochwertigen Fernverkehr der 1980er Jahre (Art. 02337 – 01602 – 01603) Deutsche Bundesbahn, Ep. III/IV Zugbildungen Personenzug mit Güterbeförderung: Gebildet aus Personen- und Güterwagen. (Art. Lok aus 01585 – 13003 – 13013 – 13006 – 01574) Nahgüterzug der 1980er Jahre. (Art. 04634 – 15241 – 01582 – 14479 – 15610) Intercity der Ep. IV. (Art. 02431 – 13530 – 13697 – 3 x 16500) Durchgangsgüterzug der 1960er Jahre: Loks mit Kabinentender machten den Packwagen für den Aufenthalt des Güterzug-Begleitpersonals entbehrlich. (Art. 02093 – 01587 – 14576 – 2 x 17150) Schnellzug Anfang der Epoche IV. (Art. 02451 – 2 x 16941 – 16971 – 16901 – 16921) Internationaler Schnellgüterzug TEEM (Trans Europ Express Marchandises): Diese Züge – meist bestehend aus gedeckten Wagen – fuhren in festen Relationen durch mehrere europäische Länder. (Art. 02500 – 17152 – 17151 – 14691 – 15830 – 15495) Schnellzug der 1980er Jahre. (Art. 02382 – 13676 – 13677 – 13677 – 13678 – 13517) Deutsche Bahn AG Zugbildungen InterCity (IC): Als IC verkehren bei der DB AG schnellfahrende Fernverkehrszüge, die aus höherwertigem Wagenmaterial zusammengestellt sind. In der Übergangszeit zwischen alter und neuer IC-Lackierung wurden häufig Fahrzeuge beider Farbschemen miteinander kombiniert. -

BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG-STIPENDIUM SEMESTER ABROAD Personal Experience Report

BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG-STIPENDIUM SEMESTER ABROAD Personal Experience Report Name: Yousef Al-Shawesh E-mail address: [email protected] Home university: Multimedia University, Cyberjaya (Malaysia) Host university: Hochschule Offenburg University of Applied Sciences, Offenburg (Germany) Period of the exchange: 10.2016 to 02.2017 (Winter Semester 2016/17) Report creation date: 30.03.2017 ☒ I hereby agree to my personal report being published on the websites of the Baden-Württemberg- STIPENDIUM (www.bw-stipendium.de) and of the Baden-Württemberg Stiftung (www.bwstiftung.de). 0 0 1 PREPARATIONS FOR THE STAY ABROAD very first time in Europe, learning new cultures, meeting new people and at the same time enjoying my stay after two During the past three years, I was eagerly seeking new stressful weeks of exams. opportunities to study in one of the best partner universities Furthermore, Hochschule Offenburg runs a buddy program for in Germany until the moment I noticed an announcement at helping new incoming international students during their the home university website for Baden-Württemberg initial days. My buddy and I were already in touch via e-mail scholarship notification forwarded by Hochschule Offenburg long before I arrived in Germany and she was very helpful and which became my favourite after knowing that it is supporting friendly. international students extensively and it also offers courses I arrived in Germany at 10 O’clock in the morning after 18 being conducted in English language. hours of flight to Frankfurt Airport. I then took the high speed I did not ponder this opportunity twice and I immediately train ICE to Offenburg station where my buddy tutor was began preparing all the required documents which took me a already there waiting for me as we had pre-arranged our week as I had to obtain an approval from the dean of Faculty meeting to pick me up to the students residence hall by bus. -

Jakobusblättle N R

JAKOBUSBLÄTTLE N R. 46 DEZEMBER 2020 Inhalt Seite Wort des Präsidenten 1 Vorgesehene Termine – wegen Corona verschoben 4 Der Badische Jakobusweg 5 Spendenaktion Pilgerherberge „El Trasgu“ 10 Foncebadón – Europäisches Haus der Begegnung 15 Jahrestagung der Deutschen St. Jakobusgesellschaft 16 Pilgerfreunde auf dem Jakobusweg von Ulm nach Einsiedeln 19 Pilgerfreunde auf dem Himmelreich-Jakobusweg 27 Pilger berichten: Christian Thumfart: Pilgerweg nach Rom 30 Norbert Walter: Mit dem Fahrrad nach Santiago 40 Schwarzes Brett – Hinweise – Informationen 48 mpressum „Jakobusblättle“ ist eine Mitgliederzeitschrift und wird herausgegeben von der Badischen St. Jakobusgesellschaft e.V. (BStJG) Breisach-Oberrimsingen Präsident: Norbert Scheiwe Vizepräsident: Dr. Fritz Tröndlin Sekretärin: Veronika Schwarz Geschäftsstelle: Jugendwerk 1, 79206 Breisach am Rhein Ansprechpartner: Norbert Scheiwe und Veronika Schwarz Telefon: (nachmittags) 07664-409-200, Telefax: 07664-409-299 eMail: [email protected] Internet: www.badische-jakobusgesellschaft.de Bankverbindung: BStJG, Konto-Nr. 6008619, BLZ 680 523 28 Sparkasse Staufen-Breisach, IBAN DE86 6805 2328 0006 0086 19 Redaktion: Paul Hahn, Karl Uhl Einzelheft: € 2,50 plus Versand, für Mitglieder kostenlos Druck: www.bis500druck.de Copyright: bei der BStJG und den jeweiligen Autoren Jakobusvereinigungen können - soweit keine fremden Rechte entgegenstehen - Auszüge mit Quellenangaben abdrucken, ganze Beiträge mit Abdruckerlaubnis Titelbild: Der „Badische Jakobusweg“ von Nordbaden bis Breisach fertiggestellt. Titelseite des Pilgerführers für den nördlichen Teil. WORT DES PRÄSIDENTEN Liebe Leser und Freunde des „Jakobusblättle“, auch die 46. Ausgabe des „Jakobusblättle“, das zweite Heft in diesem Jahr, wird von Inhalten dominiert, die die Corona-Pandemie betreffen. Die Zahlen sprechen für sich. Genau 46.790 Pilgerinnen und Pilger haben sich bis Ende September in Santiago registrieren lassen. -

Fahrradmitnahme in Zügen Des Nahverkehrs Radkultur

g Baden-Württember Fahrradmitnahme in Zügen des Nahverkehrs RadKULTUR www.3-loewen-takt.de Fahrradmitnahme in Zügen des Nahverkehrs des Zügen in Fahrradmitnahme -Takt-Übersichtskarte n e w ö Allgemeine Hinweise zur Fahrradmitnahme 3-L Tipps für eine entspannte Reise – Auf dem Bahnsteig Rad fährt Bahn Mobile Ideen für Radfahrer mit und ohne Fahrrad Für Nahverkehrszüge gibt es in der Regel keinen Wagen- Wo sich Fahrradstellplätze befinden, ist außen am Zug ge- • Lassen Sie Fahrgästen mit Kinderwagen oder Rollstuhl standsanzeiger. Hier orientieren sich Radfahrer an den kennzeichnet. Viele Nahverkehrszüge haben breite Türen, Bus&Bahn-App den Vortritt. Fahrradsymbolen, die gut sichtbar außen am Zug ange- einen stufenlosen Einstieg und Mehrzweckbereiche, die Die Fahrplanauskunft für unterwegs. Mit der kos- bracht sind. genug Platz für mehrere Räder bieten. Auf einigen Strecken tenlosen „Bus&Bahn-App“ des 3-Löwen-Takts • Nehmen Sie Packtaschen vom Fahrrad ab, bevor Sie sind noch ältere Wagen im Einsatz, bei denen man mit www.3-loewen-takt.de einsteigen. können Sie jederzeit und überall die mobile Fahr- schmalen Türen und hohen Stufen rechnen muss. planauskunft für Baden-Württemberg aufrufen. • Sprechen Sie ggf. Mitreisende an, die Klappsitze freizu- www.3-loewen-takt.de/apps/bus-bahn-app geben. Im Nahverkehr gibt es keine Reservierungsmöglichkeit für • Klären Sie, wer zu welchem Zielbahnhof möchte. Das Fahrradstellplätze. Räder werden mitgenommen, solange Radroutenplaner-App erleichtert das Ausparken der Räder und das Aussteigen. Platz ist. Gruppen melden ihren Fahrtwunsch bitte im Vor- Das umfassende Angebot des Radroutenplaners • Befolgen Sie die Hinweise der Zugbegleiter. feld mind. eine Woche vor Fahrt beim jeweiligen Eisenbahn- Baden-Württemberg gibt es auch für unterwegs. -

Wortschatz Bahntechnik/Transportwesen Deutsch-Englisch-Deutsch (Skript 0-7)

Fakultät für Architektur, Bauingenieurwesen und Stadtplanung Lehrstuhl Eisenbahnwesen Wortschatz Bahntechnik/Transportwesen Deutsch-Englisch-Deutsch (Skript 0-7) Stand 15.12.17 Zusammengestellt von Prof. Dr.-Ing. Thiel Literaturhinweise: Boshart, August u. a.: Eisenbahnbau und Eisenbahnbetrieb in sechs Sprachen. 884 S., ca. 4700 Begriffe, 2147 Abbildungen und Formeln. Reihe Illustrierte Technische Wör- terbücher (I.T.W.), Band 5. 1909, München/Berlin, R. Oldenburg Verlag. Brosius, Ignaz: Wörterbuch der Eisenbahn-Materialien für Oberbau, Werkstätten, Betrieb und Telegraphie, deren Vorkommen, Gewinnung, Eigenschaften, Fehler und Fälschungen, Prüfung u. Abnahme, Lagerung, Verwendung, Gewichte, Preise ; Handbuch für Eisen- bahnbeamte, Studirende technischer Lehranstalten und Lieferanten von Eisenbahnbe- darf. Wiesbaden, Verlag Bergmann, 1887 Dannehl, Adolf [Hrsg.]: Eisenbahn. englisch, deutsch, französisch, russisch ; mit etwa 13000 Wortstellen. Technik-Wörterbuch, 1. Aufl., Berlin. M. Verlag Technik, 1983 Lange, Ernst: Wörterbuch des Eisenbahnwesens. englisch - deutsch. 1. Aufl., Bielefeld, Reichsbahngeneraldirektion, 1947 Schlomann, Alfred (Hrsg.): Eisenbahnmaschinenwesen in sechs Sprachen. Reihe Illustrierte technische Wörterbücher (I.T.W.), Band 6. 2. Auflage. München/Berlin, R. Oldenburg Verlag. UIC Union Internationale des Chemins de Fer: UIC RailLexic 5.0 Dictionary in 22 Sprachen. 2015 Achtung! Diese Sammlung darf nur zu privaten Zwecken genutzt werden. Jegliche Einbindung in kommerzielle Produkte (Druckschriften, Vorträge, elektronische -

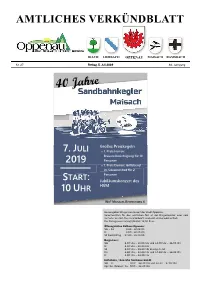

Verkündblatt KW 27 2019

AMTLICHESVERKÜNDBLATT IBACH LIERBACH OPPENAU MAISACH RAMSBACH Nr. 27 Freitag, 5. JuliJuli 2019 86. Jahrgang » » Herausgeber: Bürgermeisteramt der Stadt Oppenau. Verantwortlich für den amtlichen Teil ist der Bürgermeister oder sein Vertreter im Amt. Das Verkündblatt erscheint einmal wöchentlich. Der Bezugspreis beträgt jährlich 16,50 Euro. Öffnungszeiten Rathaus Oppenau: Mo – Do 8.00 - 12.00 Uhr Fr 8.00 - 12.30 Uhr Mi Nachmittag 14.00 - 18.30 Uhr Bürgerbüro: Mo 8.00 Uhr – 12.00 Uhr und 14.00 Uhr – 16.00 Uhr Di 8.00 Uhr – 12.00 Uhr Mi 8.00 Uhr – 18.30 Uhr durchgehend Do 8.00 Uhr – 12.00 Uhr und 14.00 Uhr – 16.00 Uhr Fr 8.00 Uhr – 12.30 Uhr Kulturbüro / Renchtal Tourismus GmbH: Mo – Fr: 9.00 – 12.30 Uhr und 13.30 – 17.00 Uhr April bis Oktober: Sa: 9.00 – 12.30 Uhr 2 Gemeindeamtliche Bekanntmachungen Lieber Mitbürgerinnen und Mitbürger, für die Unannehmlichkeiten und unzumutbaren Zustände durch geparkte PKW´s im Bereich des Schwimmbades am vergangenen Sonntag möchte ich mich bei Ihnen und insbesonders bei allen Anwohnern entschuldigen. Ich hoffe, dass das in dieser Intensität eine Ausnahme bleibt. Die Stadt Oppenau möchte dem dennoch entgegen- wirken und wird die Wiese bei der Günter-Bimmerle- Halle als weiteren, behelfsmäßigen Parkplatz zur Verfü- gung stellen. Zudem wird in der Straße „Im Birket“ ein Parkverbot angeordnet. Die Besucher des Schwimmbades werden gebeten, aus Rücksicht auf die Anwohner auf den ausgewiesenen Einweihung Bolzplatz am Jugendtreff Chill Parkplätzen des Schwimmbades zu parken und sich im Es ist soweit! Übrigen an die straßenverkehrsrechtlichen Regeln zu Dank der großzügigen Spende der Firma Doll, der finanzi- halten. -

European Train Names: a Historic Outline Christian Weyers

ONOMÀSTICA BIBLIOTECA TÈCNICA DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA European Train Names: a Historic Outline* Christian Weyers DOI: 10.2436/15.8040.01.201 Abstract This paper gives a first overview of the onomastic category of train names, searches to classify the corpus and reviews different stages of their productivity. Apart from geographical names (toponyms, choronyms, compass directions) generally indicating points of origin and destination of the trains in question, a considerable number of personal names have entered this category, of classical literary authors, musicians and scientists, but also of many fictional or non-fictional characters taken from literature or legendary traditions. In some cases also certain symbolic attributes of these persons and finally even heraldic figures have given their names to trains. In terms of their functionality, train names originally were an indicator of exclusiveness and high grade of travel quality, but they developed gradually, as they dispersed over the European continent, into a rather unspecific, generalized appellation, also for regional and local trains. After two periods of prosperity after 1950, the privatisation of railway companies starting in the 1990s had again a very positive effect on the category, as the number of named trains initially reached a new record in this decade. ***** The first train names appeared in England in the 1860s in addition to names for steam locomotives, and on two different levels. The Special Scotch Express between London King’s Cross and Edinburgh (inaugurated in 1862) was called by the public The Flying Scotsman from the 1870s, but it succeeded as the official name not before 1924. Also the names of the German diesel trainsets Der Fliegende Hamburger and Der Fliegende Kölner were colloquial name creations, as were the Train Bleu and the Settebello operated from 1922 and 1953 but officially named in 1947 and 1958, respectively. -

Von Der Ludwigsbahn Zum Integralen Taktfahrplan Teil 2

Fritz Engbarth Von der Ludwigsbahn zum Integralen Taktfahrplan 160 Jahre Eisenbahnverkehr in der Pfalz Teil 2 Hrsg.: Zweckverband SPNV Rheinland-Pfalz Süd Ein Land spart Zeit – Neue Mobilität mit dem Rheinland-Pfalz-Takt Ein Land spart Zeit – Neue Mobilität mit dem Rheinland-Pfalz-Takt Ein Land spart Zeit – Neue Mobilität mit dem Rheinland-Pfalz-Takt Nach vielen Streckenstilllegungen Wir erinnern uns: Ab Mitte der 1970er Jahre erreichte die Stilllegungswelle auch in startete 1994 in der Pfalz ein neues Rheinland-Pfalz einen Höhepunkt. An den verlassenen Bahnsteigen ehemaliger Bahnzeitalter. Statt der Verab- Schnellzugstrecken wie Germersheim – Landau oder Monsheim – Langmeil wuchs schiedung des letzten Zuges wurde das Unkraut. Die landesweite Netzdichte erreichte 1990 einen Wert von lediglich mit der Linie Grünstadt – Eisenberg 0,069 km/qkm Fläche – grobmaschiger war Als Start in die neue Epoche kann der Einsatz der VT 628 gewertet werden. Bei einer Vorstellungsfahrt im Jahr 1987 traf er auf das Streckennetz nur noch in Schleswig- seinen Vorgänger, den ebenso robusten Schienenbus. erstmals abseits eines Verdichtungs- Holstein. Vereinbarung aufgenommen. Obwohl im schäftsführers des VRN, Werner Schreiner – raumes der Personenzugverkehr auf Mit der „Vereinbarung zwischen dem Land Norden des Landes die Eifelquerbahn noch mit dem Bau des Haltepunktes Neustadt- Rheinland-Pfalz und der Deutschen Bundes- im Januar 1991 den Personenverkehr verlor, Böbig der Schülerverkehr von der Straße auf einer zuvor stillgelegten Strecke bahn über die zukünftige Gestaltung des stellte die Vereinbarung einen wichtigen die Schiene verlagert. Im Jahre 1991 machte Öffentlichen Personennahverkehrs“ vom Schritt zur Erhaltung des Schienenverkehrs diese Bahnstrecke dann nochmals von sich wieder eingeführt. Fortan machte 9. Juni 1986 griff das Land nach dem Vorbild im ländlichen Raum dar. -

89 Seiten, Größe Ca. 3,6 MB

=== VD -T === Der Virtuelle Deutschland-Takt = Strecken 360 - 427 + 482 - 499 = SUEDNIEDER SACHSEN + OSTWESTFALEN Hamburg Bremen Hannover Dortm. Le ipz Köln Frankfurt Ein Integraler Taktfahrplan von Jörg Schäfer Übersichtskarte mit den VD-T- Kursbuchnummern Lila hervorgehoben sind die wichtigsten Verbes- serungen seit 1990. Franken in Takt (FiT), 830 - 869 Oberfranken-Ost und Oberpfalz - Seite 2 Grafischer Fahrplan der Normalverkehrszeit: Jede Linie ist eine Zugfahrt im Stundentakt Franken in Takt (FiT), www.franken-in-takt.de , © Jörg Schäfer, Juni 2016 - Seite 3 Der Virtuelle Deutschland-Takt (VD-T), Strecken-Nr. 600 - 634 = HESSEN - Seite 4 Schnellfahrstrecke Hannover - Göttingen (- Kassel) Beim VD-T wäre die Schnellfahrtstrecke (SFS) von Hannover bis Kassel-Wilhelms- höhe in den 1980er Jahren wie in der Re- alität gebaut worden. Die Zahl der stündli- chen ICE-Linien wäre dann in der Folgezeit dank der besseren Rahmenbedingungen und der größeren Nachfrage noch stärker als in der Realität gewachsen. Für die 120.000 Einwohner von Göttingen sind mehr als zwei ICE-Stopps pro Stunde und Richtung aber nicht erforderlich. Daher baut der VD-T 20 km weiter nördlich den Almstedt Bahnhof Northeim (30.000 Einwohner) so aus, dass die „weiße Flotte“ auch dort halten kann. Der Fahrplan der ICE-Linie 4 ist so günstig, dass sich deren Züge zur Minute 00 in Northeim begegnen und optimale Anschlüsse ins Umland bieten. Auf den später gebauten Neubaustrecken Köln - Frankfurt und Stuttgart - Ulm sollen Kreiensen beim VD-T 200 km/h schnelle IRE auch kleinere Städte bedienen. Das würde auch zwischen Hannover und Göttingen Begehr- lichkeiten wecken, denn der IC braucht auf Northeim der Altstrecke für die 110 km 67 Minuten. -

Fahrplanentwicklung Bei Den SBB Von 1929 Bis 1985 Thomas Matti

Berner Studien zur Geschichte Reihe 3: Verkehr, Mobilität, Tourismus und Kommunikation in der Geschichte Band 1 Thomas Matti Fahrplanentwicklung bei den SBB von 1929 bis 1985 Partizipation und Mobilitätsinteressen analysiert anhand von Fahrplanbegehren Berner Studien zur Geschichte Reihe 3: Verkehr, Mobilität, Tourismus und Kommunikation in der Geschichte Band 1 Herausgegeben von Christian Rohr Historisches Institut der Universität Bern Thomas Matti Fahrplanentwicklung bei den SBB von 1929 bis 1985 Partizipation und Mobilitätsinteressen analysiert anhand von Fahrplanbegehren Abteilung Wirtschafts-, Sozial- und Umweltgeschichte (WSU) Historisches Institut Universität Bern Schweiz Bern Open Publishing BOP bop.unibe.ch 2019 Impressum ISBN: 978-3-906813-54-7 ISSN: 2571-6794 DOI: 10.7892/boris.125288 Herausgeber: Christian Rohr Historisches Institut Universität Bern Längassstrasse 49 CH-3012 Bern Lektorat: Isabelle Vieli Layout Titelei: Daniel Burkhard This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Text © 2019, Thomas Matti Titelfoto: Depot Erstfeld in Uri, SBB Historic https://pixabay.com/de/sbb-historic-depot- erstfeld-uri-1578546/ INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 1. EINLEITUNG 7 1.1. ERKENNTNISLEITENDE FRAGESTELLUNG 8 1.2. EINGRENZUNG DES THEMAS 8 1.3. QUELLENLAGE 9 1.4. FORSCHUNGSSTAND 10 1.5. THEORETISCHE UND METHODISCHE EINBETTUNG 14 1.5.1. THEORETISCHER ANSATZ 14 1.5.2. METHODISCHER ANSATZ 16 1.6. AUFBAU DER ARBEIT 19 2. FAHRPLÄNE UND FAHRPLANBEGEHREN 20 2.1. FAHRPLANARTEN UND FUNKTIONSWEISE 20 2.2. URSPRUNG DER FAHRPLANBEGEHREN 22 2.3. ABLAUF EINES BEGEHRUNGSVERFAHRENS 25 3. DAS EISENBAHNNETZ IN DEN KANTONEN AARGAU, BASEL-STADT UND GLARUS 27 4. 1929 BIS 1945: ZWISCHENKRIEGSZEIT UND ZWEITER WELTKRIEG 31 4.1. -

Minitrix New Items 2019 Posted

New Items 2019 Minitrix. The Fascination of the Original. E minitrix_nh2019_U1_U4.indd 3 28.12.18 08:42 Dear Minitrix Fans, Welcome to the new items for 2019 and the 60th anniversary of Minitrix. You could believe that this might be the reason why you presently have an independent Minitrix new items brochure in your hands, but that is not so – it was your ideas and wishes that prompted us to put out your own brochure again. With products and accessories tailor made to a point of view at 1:160. Sprinkled with new Minitrix tooling and popular car compositions, in the next 64 pages we are going to take you on a journey through the railroad eras and also show you some curiosities. MHI Exclusiv 1/2019 2 – 11 So for example, the express service car that became famous beyond Minitrix Club Model for 2019 8– 9 Cologne. Later, it did not keep its place and it was therefore sent by the Starter Sets 12 – 17 railroad management to Berlin. Or, the express train passenger cars of Minitrix “my Hobby” 18 – 21 the Baltic-Orient Express that became famous. Austria 45 For anyone with a passion for collecting, we recommend opening Switzerland 48 – 50 page 48. Here you will encounter a reptile that is exceptionally rare France 51 – 53 and that is also celebrating an anniversary. Poland 54 Czech Republic 54 – 55 Whether it is regional service or long distance connections by IC, Netherlands 56 maintaining branch lines in the early Twenties or rather modern freight Building Kits 56 – 57 service – In these new items, we are presenting you with a broad Trix Club 58 assortment of locomotives, cars, and accessories across all of the Trix Club Cars for 2019 59 railroad eras. -

Weiterentwicklung Des SPNV in Der Region Donau-Iller Vorstudie Für Die Machbarkeit Einer Regio-S-Bahn Donau-Iller

Weiterentwicklung des SPNV in der Region Donau-Iller Vorstudie für die Machbarkeit einer Regio-S-Bahn Donau-Iller Bericht Vorstudie (Entwurf) Oktober 2010 Gubelstrasse 28 Orleansplatz 5a CH-8050 Zürich 81667 München Ansprechpartner: Ansprechpartner: Georges Rey Frank Schäfer Tel +41-44-317 50 74 Tel. (089) 45 91 11 04 [email protected] [email protected] LukasRegli Dr.-Ing.UlrichRückert Tel+41-44-3175523 Tel.(089)45911148 [email protected] [email protected] Auftraggeber Regionalverband Donau-Iller Schwambergerstraße 35 89073 Ulm Unter Mitfinanzierung von Freistaat Bayern Land Baden-Württemberg Regionalverband Ostwürttemberg Landkreis Alb-Donau-Kreis Landkreis Biberach Landkreis Günzburg Landkreis Neu-Ulm Landkreis Unterallgäu Stadt Memmingen Stadt Ulm INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 1 Aufgabenstellung 3 1.1 Ausgangslage 3 1.2 Zielsetzung 3 2 Methodik / Planungsablauf 5 2.1 Der Integrale Taktfahrplan 5 2.2 Planungsmethodik für die Regio-S-Bahn Donau-Iller 7 3 Randbedingungen 8 3.1 Räumliche Abgrenzung 8 3.2 Fahrplan 2010 9 3.2.1 Ulm – Stuttgart (Filstalbahn), Kursbuchstrecke (KBS) 750 9 3.2.2 Ulm – Augsburg, KBS 980 9 3.2.3 Ulm – Aalen (Brenzbahn), KBS 757 10 3.2.4 Ulm – Memmingen – Kempten (Illertalbahn), KBS 756 11 3.2.5 Ulm – Aulendorf – Friedrichshafen (Südbahn), KBS 751 11 3.2.6 Ulm – Ehingen – Sigmaringen (Donaubahn), KBS 755 12 3.2.7 Streckencharakteristika 13 3.3 Bestehende Planungen 13 3.4 Projektideen 14 3.5 Umsetzungsstand des ÖPNV-Modellprojekts Region Ulm / Neu-Ulm 16 3.6 Weiterentwicklungsvorschläge der Gebietskörperschaften