Chapter 06 Equipartition of Energy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entropy: Ideal Gas Processes

Chapter 19: The Kinec Theory of Gases Thermodynamics = macroscopic picture Gases micro -> macro picture One mole is the number of atoms in 12 g sample Avogadro’s Number of carbon-12 23 -1 C(12)—6 protrons, 6 neutrons and 6 electrons NA=6.02 x 10 mol 12 atomic units of mass assuming mP=mn Another way to do this is to know the mass of one molecule: then So the number of moles n is given by M n=N/N sample A N = N A mmole−mass € Ideal Gas Law Ideal Gases, Ideal Gas Law It was found experimentally that if 1 mole of any gas is placed in containers that have the same volume V and are kept at the same temperature T, approximately all have the same pressure p. The small differences in pressure disappear if lower gas densities are used. Further experiments showed that all low-density gases obey the equation pV = nRT. Here R = 8.31 K/mol ⋅ K and is known as the "gas constant." The equation itself is known as the "ideal gas law." The constant R can be expressed -23 as R = kNA . Here k is called the Boltzmann constant and is equal to 1.38 × 10 J/K. N If we substitute R as well as n = in the ideal gas law we get the equivalent form: NA pV = NkT. Here N is the number of molecules in the gas. The behavior of all real gases approaches that of an ideal gas at low enough densities. Low densitiens m= enumberans tha oft t hemoles gas molecul es are fa Nr e=nough number apa ofr tparticles that the y do not interact with one another, but only with the walls of the gas container. -

On the Equation of State of an Ideal Monatomic Gas According to the Quantum-Theory, In: KNAW, Proceedings, 16 I, 1913, Amsterdam, 1913, Pp

Huygens Institute - Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW) Citation: W.H. Keesom, On the equation of state of an ideal monatomic gas according to the quantum-theory, in: KNAW, Proceedings, 16 I, 1913, Amsterdam, 1913, pp. 227-236 This PDF was made on 24 September 2010, from the 'Digital Library' of the Dutch History of Science Web Center (www.dwc.knaw.nl) > 'Digital Library > Proceedings of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW), http://www.digitallibrary.nl' - 1 - 227 high. We are uncertain as to the cause of this differencc: most probably it is due to an nncertainty in the temperature with the absolute manometer. It is of special interest to compare these observations with NERNST'S formula. Tbe fourth column of Table II contains the pressUl'es aceord ing to this formula, calc111ated witb the eonstants whieb FALCK 1) ha~ determined with the data at bis disposal. FALOK found the following expression 6000 1 0,009983 log P • - --. - + 1. 7 5 log T - T + 3,1700 4,571 T . 4,571 where p is the pressure in atmospheres. The correspondence will be se en to be satisfactory considering the degree of accuracy of the observations. 1t does riot look as if the constants could be materially improved. Physics. - "On the equation of state oj an ideal monatomic gflS accoJ'ding to tlw quantum-the01'Y." By Dr. W. H. KEEsmr. Supple ment N°. 30a to the Oommunications ft'om the PhysicaL Labora tory at Leiden. Oommunicated by Prof. H. KAl\IERLINGH ONNES. (Communicated in the meeting of May' 31, 1913). -

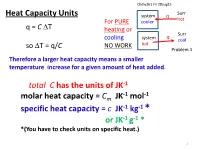

Total C Has the Units of JK-1 Molar Heat Capacity = C Specific Heat Capacity

Chmy361 Fri 28aug15 Surr Heat Capacity Units system q hot For PURE cooler q = C ∆T heating or q Surr cooling system cool ∆ C NO WORK hot so T = q/ Problem 1 Therefore a larger heat capacity means a smaller temperature increase for a given amount of heat added. total C has the units of JK-1 -1 -1 molar heat capacity = Cm JK mol specific heat capacity = c JK-1 kg-1 * or JK-1 g-1 * *(You have to check units on specific heat.) 1 Which has the higher heat capacity, water or gold? Molar Heat Cap. Specific Heat Cap. -1 -1 -1 -1 Cm Jmol K c J kg K _______________ _______________ Gold 25 129 Water 75 4184 2 From Table 2.2: 100 kg of water has a specific heat capacity of c = 4.18 kJ K-1kg-1 What will be its temperature change if 418 kJ of heat is removed? ( Relates to problem 1: hiker with wet clothes in wind loses body heat) q = C ∆T = c x mass x ∆T (assuming C is independent of temperature) ∆T = q/ (c x mass) = -418 kJ / ( 4.18 kJ K-1 kg-1 x 100 kg ) = = -418 kJ / ( 4.18 kJ K-1 kg-1 x 100 kg ) = -418/418 = -1.0 K Note: Units are very important! Always attach units to each number and make sure they cancel to desired unit Problems you can do now (partially): 1b, 15, 16a,f, 19 3 A Detour into the Microscopic Realm pext Pressure of gas, p, is caused by enormous numbers of collisions on the walls of the container. -

Ideal Gasses Is Known As the Ideal Gas Law

ESCI 341 – Atmospheric Thermodynamics Lesson 4 –Ideal Gases References: An Introduction to Atmospheric Thermodynamics, Tsonis Introduction to Theoretical Meteorology, Hess Physical Chemistry (4th edition), Levine Thermodynamics and an Introduction to Thermostatistics, Callen IDEAL GASES An ideal gas is a gas with the following properties: There are no intermolecular forces, except during collisions. All collisions are elastic. The individual gas molecules have no volume (they behave like point masses). The equation of state for ideal gasses is known as the ideal gas law. The ideal gas law was discovered empirically, but can also be derived theoretically. The form we are most familiar with, pV nRT . Ideal Gas Law (1) R has a value of 8.3145 J-mol1-K1, and n is the number of moles (not molecules). A true ideal gas would be monatomic, meaning each molecule is comprised of a single atom. Real gasses in the atmosphere, such as O2 and N2, are diatomic, and some gasses such as CO2 and O3 are triatomic. Real atmospheric gasses have rotational and vibrational kinetic energy, in addition to translational kinetic energy. Even though the gasses that make up the atmosphere aren’t monatomic, they still closely obey the ideal gas law at the pressures and temperatures encountered in the atmosphere, so we can still use the ideal gas law. FORM OF IDEAL GAS LAW MOST USED BY METEOROLOGISTS In meteorology we use a modified form of the ideal gas law. We first divide (1) by volume to get n p RT . V we then multiply the RHS top and bottom by the molecular weight of the gas, M, to get Mn R p T . -

Thermodynamics Molecular Model of a Gas Molar Heat Capacities

Thermodynamics Molecular Model of a Gas Molar Heat Capacities Lana Sheridan De Anza College May 7, 2020 Last time • heat capacities for monatomic ideal gases Overview • heat capacities for diatomic ideal gases • adiabatic processes Quick Recap For all ideal gases: 3 3 K = NK¯ = Nk T = nRT tot,trans trans 2 B 2 and ∆Eint = nCV ∆T For monatomic gases: 3 E = K = nRT int tot,trans 2 and so, 3 C = R V 2 and 5 C = R P 2 Reminder: Kinetic Energy and Internal Energy In a monatomic gas the three translational motions are the only degrees of freedom. We can choose 3 3 E = K = N k T = nRT int tot,trans 2 B 2 (This is the thermal energy, so the bond energy is zero { if we liquify the gas the bond energy becomes negative.) Equipartition Consequences in Diatomic Gases Reminder: Equipartition of energy theorem Each degree of freedom for each molecule contributes an and 1 additional 2 kB T of energy to the system. A monatomic gas has 3 degrees of freedom: it can have translational KE due to motion in 3 independent directions. A diatomic gas has more ways to move and store energy. It can: • translate • rotate • vibrate 21.3 The Equipartition of Energy 635 Equipartition21.3 The Equipartition Consequences of Energy in Diatomic Gases Predictions based on our model for molar specific heat agree quite well with the Contribution to internal energy: Translational motion of behavior of monatomic gases, but not with the behavior of complex gases (see Table the center of mass 21.2). -

Chapter 5. Calorimetiric Properties

Chapter 5. Calorimetiric Properties (1) Specific and molar heat capacities (2) Latent heats of crystallization or fusion A. Heat Capacity - The specific heat capacity is the heat which must be added per kg of a substance to raise the temperature by one degree 1. Specific heat capacity at const. Volume ∂U c = (J/kg· K) v ∂ T v 2. Specific heat capacity at cont. pressure ∂H c = (J/kg· K) p ∂ T p 3. molar heat capacity at constant volume Cv = Mcv (J/mol· K) 4. molar heat capacity at constat pressure ∂H C = M = (J/mol· K) p cp ∂ T p Where H is the enthalpy per mol ◦ Molar heat capacity of solid and liquid at 25℃ s l - Table 5.1 (p.111)에 각각 group 의 Cp (Satoh)와 Cp (Show)에 대한 data 를 나타내었다. l s - Table 5.2 (p.112,113)에 각 polymer 에 대한 Cp , Cp 값들을 나타내었다. - (Ex 5.1)에 polypropylene 의 Cp 를 구하는 것을 나타내었다. - ◦ Specific heat as a function of temperature - 그림 5.1 에 polypropylene 의 molar heat capacity 에 대한 그림을 나타 내었다. ◦ The slopes of the heat capacity for solid polymer dC s 1 p = × −3 s 3 10 C p (298) dt dC l 1 p = × −3 l 1.2 10 C p (298) dt l s (see Table 5.3) for slope of the Cp , Cp ◦ 식 (5.1)과 (5.2)에 온도에 따른 Cp 값 계산 (Ex) calculate the heat capacity of polypropylene with a degree of crystallinity of 30% at 25℃ (p.110) (sol) by the addition of group contributions (see table 5.1) s l Cp (298K) Cp (298K) ( -CH2- ) 25.35 30.4(from p.111) ( -CH- ) 15.6 20.95 ( -CH3 ) 30.9 36.9 71.9 88.3 ∴ Cp(298K) = 0.3 (71.9J/mol∙ K) + 0.7(88.3J/mol∙ K) = 83.3 (J/mol∙ K) - It is assumed that the semi crystalline polymer consists of an amorphous fraction l s with heat capacity Cp and a crystalline Cp P 116 Theoretical Background P 117 The increase of the specific heat capacity with temperature depends on an increase of the vibrational degrees of freedom. -

Equipartition of Energy

Equipartition of Energy The number of degrees of freedom can be defined as the minimum number of independent coordinates, which can specify the configuration of the system completely. (A degree of freedom of a system is a formal description of a parameter that contributes to the state of a physical system.) The position of a rigid body in space is defined by three components of translation and three components of rotation, which means that it has six degrees of freedom. The degree of freedom of a system can be viewed as the minimum number of coordinates required to specify a configuration. Applying this definition, we have: • For a single particle in a plane two coordinates define its location so it has two degrees of freedom; • A single particle in space requires three coordinates so it has three degrees of freedom; • Two particles in space have a combined six degrees of freedom; • If two particles in space are constrained to maintain a constant distance from each other, such as in the case of a diatomic molecule, then the six coordinates must satisfy a single constraint equation defined by the distance formula. This reduces the degree of freedom of the system to five, because the distance formula can be used to solve for the remaining coordinate once the other five are specified. The equipartition theorem relates the temperature of a system with its average energies. The original idea of equipartition was that, in thermal equilibrium, energy is shared equally among all of its various forms; for example, the average kinetic energy per degree of freedom in the translational motion of a molecule should equal that of its rotational motions. -

Fastest Frozen Temperature for a Thermodynamic System

Fastest Frozen Temperature for a Thermodynamic System X. Y. Zhou, Z. Q. Yang, X. R. Tang, X. Wang1 and Q. H. Liu1, 2, ∗ 1School for Theoretical Physics, School of Physics and Electronics, Hunan University, Changsha, 410082, China 2Synergetic Innovation Center for Quantum Effects and Applications (SICQEA), Hunan Normal University,Changsha 410081, China For a thermodynamic system obeying both the equipartition theorem in high temperature and the third law in low temperature, the curve showing relationship between the specific heat and the temperature has two common behaviors: it terminates at zero when the temperature is zero Kelvin and converges to a constant value of specific heat as temperature is higher and higher. Since it is always possible to find the characteristic temperature TC to mark the excited temperature as the specific heat almost reaches the equipartition value, it is also reasonable to find a temperature in low temperature interval, complementary to TC . The present study reports a possibly universal existence of the such a temperature #, defined by that at which the specific heat falls fastest along with decrease of the temperature. For the Debye model of solids, below the temperature # the Debye's law manifest itself. PACS numbers: I. INTRODUCTION A thermodynamic system usually obeys two laws in opposite limits of temperature; in high temperature the equipar- tition theorem works and in low temperature the third law of thermodynamics holds. From the shape of a curve showing relationship between the specific heat and the temperature, the behaviors in these two limits are qualitatively clear: in high temperature it approaches to a constant whereas it goes over to zero during the temperature is lowering to the zero Kelvin. -

Atkins' Physical Chemistry

Statistical thermodynamics 2: 17 applications In this chapter we apply the concepts of statistical thermodynamics to the calculation of Fundamental relations chemically significant quantities. First, we establish the relations between thermodynamic 17.1 functions and partition functions. Next, we show that the molecular partition function can be The thermodynamic functions factorized into contributions from each mode of motion and establish the formulas for the 17.2 The molecular partition partition functions for translational, rotational, and vibrational modes of motion and the con- function tribution of electronic excitation. These contributions can be calculated from spectroscopic data. Finally, we turn to specific applications, which include the mean energies of modes of Using statistical motion, the heat capacities of substances, and residual entropies. In the final section, we thermodynamics see how to calculate the equilibrium constant of a reaction and through that calculation 17.3 Mean energies understand some of the molecular features that determine the magnitudes of equilibrium constants and their variation with temperature. 17.4 Heat capacities 17.5 Equations of state 17.6 Molecular interactions in A partition function is the bridge between thermodynamics, spectroscopy, and liquids quantum mechanics. Once it is known, a partition function can be used to calculate thermodynamic functions, heat capacities, entropies, and equilibrium constants. It 17.7 Residual entropies also sheds light on the significance of these properties. 17.8 Equilibrium constants Checklist of key ideas Fundamental relations Further reading Discussion questions In this section we see how to obtain any thermodynamic function once we know the Exercises partition function. Then we see how to calculate the molecular partition function, and Problems through that the thermodynamic functions, from spectroscopic data. -

Exercise 18.4 the Ideal Gas Law Derived

9/13/2015 Ch 18 HW Ch 18 HW Due: 11:59pm on Monday, September 14, 2015 To understand how points are awarded, read the Grading Policy for this assignment. Exercise 18.4 ∘ A 3.00L tank contains air at 3.00 atm and 20.0 C. The tank is sealed and cooled until the pressure is 1.00 atm. Part A What is the temperature then in degrees Celsius? Assume that the volume of the tank is constant. ANSWER: ∘ T = 175 C Correct Part B If the temperature is kept at the value found in part A and the gas is compressed, what is the volume when the pressure again becomes 3.00 atm? ANSWER: V = 1.00 L Correct The Ideal Gas Law Derived The ideal gas law, discovered experimentally, is an equation of state that relates the observable state variables of the gaspressure, temperature, and density (or quantity per volume): pV = NkBT (or pV = nRT ), where N is the number of atoms, n is the number of moles, and R and kB are ideal gas constants such that R = NA kB, where NA is Avogadro's number. In this problem, you should use Boltzmann's constant instead of the gas constant R. Remarkably, the pressure does not depend on the mass of the gas particles. Why don't heavier gas particles generate more pressure? This puzzle was explained by making a key assumption about the connection between the microscopic world and the macroscopic temperature T . This assumption is called the Equipartition Theorem. The Equipartition Theorem states that the average energy associated with each degree of freedom in a system at T 1 k T k = 1.38 × 10−23 J/K absolute temperature is 2 B , where B is Boltzmann's constant. -

Lecture 8 - Dec 2, 2013 Thermodynamics of Earth and Cosmos; Overview of the Course

Physics 5D - Lecture 8 - Dec 2, 2013 Thermodynamics of Earth and Cosmos; Overview of the Course Reminder: the Final Exam is next Wednesday December 11, 4:00-7:00 pm, here in Thimann Lec 3. You can bring with you two sheets of paper with any formulas or other notes you like. A PracticeFinalExam is at http://physics.ucsc.edu/~joel/Phys5D The Physics Department has elected to use the new eCommons Evaluations System to collect end of the quarter instructor evaluations from students in our courses. All students in our courses will have access to the evaluation tool in eCommons, whether or not the instructor used an eCommons site for course work. Students will receive an email from the department when the evaluation survey is available. The email will provide information regarding the evaluation as well as a link to the evaluation in eCommons. Students can click the link, login to eCommons and find the evaluation to take and submit. Alternately, students can login to ecommons.ucsc.edu and click the Evaluation System tool to see current available evaluations. Monday, December 2, 13 20-8 Heat Death of the Universe If we look at the universe as a whole, it seems inevitable that, as more and more energy is converted to unavailable forms, the total entropy S will increase and the ability to do work anywhere will gradually decrease. This is called the “heat death of the universe”. It was a popular theme in the late 19th century, after physicists had discovered the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics. Lord Kelvin calculated that the sun could only shine for about 20 million years, based on the idea that its energy came from gravitational contraction. -

Experimental Determination of Heat Capacities and Their Correlation with Theoretical Predictions Waqas Mahmood, Muhammad Sabieh Anwar, and Wasif Zia

Experimental determination of heat capacities and their correlation with theoretical predictions Waqas Mahmood, Muhammad Sabieh Anwar, and Wasif Zia Citation: Am. J. Phys. 79, 1099 (2011); doi: 10.1119/1.3625869 View online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1119/1.3625869 View Table of Contents: http://ajp.aapt.org/resource/1/AJPIAS/v79/i11 Published by the American Association of Physics Teachers Additional information on Am. J. Phys. Journal Homepage: http://ajp.aapt.org/ Journal Information: http://ajp.aapt.org/about/about_the_journal Top downloads: http://ajp.aapt.org/most_downloaded Information for Authors: http://ajp.dickinson.edu/Contributors/contGenInfo.html Downloaded 13 Aug 2013 to 157.92.4.6. Redistribution subject to AAPT license or copyright; see http://ajp.aapt.org/authors/copyright_permission Experimental determination of heat capacities and their correlation with theoretical predictions Waqas Mahmood, Muhammad Sabieh Anwar,a) and Wasif Zia School of Science and Engineering, Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), Opposite Sector U, D. H. A., Lahore 54792, Pakistan (Received 25 January 2011; accepted 23 July 2011) We discuss an experiment for determining the heat capacities of various solids based on a calorimetric approach where the solid vaporizes a measurable mass of liquid nitrogen. We demonstrate our technique for copper and aluminum, and compare our data with Einstein’s model of independent harmonic oscillators and the more accurate Debye model. We also illustrate an interesting material property, the Verwey transition