Molar Heat Capacities of a Monatomic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lab: Specific Heat

Lab: Specific Heat Summary Students relate thermal energy to heat capacity by comparing the heat capacities of different materials and graphing the change in temperature over time for a specific material. Students explore the idea of insulators and conductors in an attempt to apply their knowledge in real world applications, such as those that engineers would. Engineering Connection Engineers must understand the heat capacity of insulators and conductors if they wish to stay competitive in “green” enterprises. Engineers who design passive solar heating systems take advantage of the natural heat capacity characteristics of materials. In areas of cooler climates engineers chose building materials with a low heat capacity such as slate roofs in an attempt to heat the home during the day. In areas of warmer climates tile roofs are popular for their ability to store the sun's heat energy for an extended time and release it slowly after the sun sets, to prevent rapid temperature fluctuations. Engineers also consider heat capacity and thermal energy when they design food containers and household appliances. Just think about your aluminum soda can versus glass bottles! Grade Level: 9-12 Group Size: 4 Time Required: 90 minutes Activity Dependency :None Expendable Cost Per Group : US$ 5 The cost is less if thermometers are available for each group. NYS Science Standards: STANDARD 1 Analysis, Inquiry, and Design STANDARD 4 Performance indicator 2.2 Keywords: conductor, energy, energy storage, heat, specific heat capacity, insulator, thermal energy, thermometer, thermocouple Learning Objectives After this activity, students should be able to: Define heat capacity. Explain how heat capacity determines a material's ability to store thermal energy. -

Lecture 4: 09.16.05 Temperature, Heat, and Entropy

3.012 Fundamentals of Materials Science Fall 2005 Lecture 4: 09.16.05 Temperature, heat, and entropy Today: LAST TIME .........................................................................................................................................................................................2� State functions ..............................................................................................................................................................................2� Path dependent variables: heat and work..................................................................................................................................2� DEFINING TEMPERATURE ...................................................................................................................................................................4� The zeroth law of thermodynamics .............................................................................................................................................4� The absolute temperature scale ..................................................................................................................................................5� CONSEQUENCES OF THE RELATION BETWEEN TEMPERATURE, HEAT, AND ENTROPY: HEAT CAPACITY .......................................6� The difference between heat and temperature ...........................................................................................................................6� Defining heat capacity.................................................................................................................................................................6� -

Compression of an Ideal Gas with Temperature Dependent Specific

Session 3666 Compression of an Ideal Gas with Temperature-Dependent Specific Heat Capacities Donald W. Mueller, Jr., Hosni I. Abu-Mulaweh Engineering Department Indiana University–Purdue University Fort Wayne Fort Wayne, IN 46805-1499, USA Overview The compression of gas in a steady-state, steady-flow (SSSF) compressor is an important topic that is addressed in virtually all engineering thermodynamics courses. A typical situation encountered is when the gas inlet conditions, temperature and pressure, are known and the compressor dis- charge pressure is specified. The traditional instructional approach is to make certain assumptions about the compression process and about the gas itself. For example, a special case often consid- ered is that the compression process is reversible and adiabatic, i.e. isentropic. The gas is usually ÊÌ considered to be ideal, i.e. ÈÚ applies, with either constant or temperature-dependent spe- cific heat capacities. The constant specific heat capacity assumption allows for direct computation of the discharge temperature, while the temperature-dependent specific heat assumption does not. In this paper, a MATLAB computer model of the compression process is presented. The substance being compressed is air which is considered to be an ideal gas with temperature-dependent specific heat capacities. Two approaches are presented to describe the temperature-dependent properties of air. The first approach is to use the ideal gas table data from Ref. [1] with a look-up interpolation scheme. The second approach is to use a curve fit with the NASA Lewis coefficients [2,3]. The computer model developed makes use of a bracketing–bisection algorithm [4] to determine the temperature of the air after compression. -

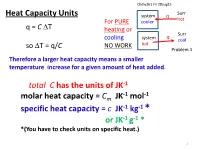

Total C Has the Units of JK-1 Molar Heat Capacity = C Specific Heat Capacity

Chmy361 Fri 28aug15 Surr Heat Capacity Units system q hot For PURE cooler q = C ∆T heating or q Surr cooling system cool ∆ C NO WORK hot so T = q/ Problem 1 Therefore a larger heat capacity means a smaller temperature increase for a given amount of heat added. total C has the units of JK-1 -1 -1 molar heat capacity = Cm JK mol specific heat capacity = c JK-1 kg-1 * or JK-1 g-1 * *(You have to check units on specific heat.) 1 Which has the higher heat capacity, water or gold? Molar Heat Cap. Specific Heat Cap. -1 -1 -1 -1 Cm Jmol K c J kg K _______________ _______________ Gold 25 129 Water 75 4184 2 From Table 2.2: 100 kg of water has a specific heat capacity of c = 4.18 kJ K-1kg-1 What will be its temperature change if 418 kJ of heat is removed? ( Relates to problem 1: hiker with wet clothes in wind loses body heat) q = C ∆T = c x mass x ∆T (assuming C is independent of temperature) ∆T = q/ (c x mass) = -418 kJ / ( 4.18 kJ K-1 kg-1 x 100 kg ) = = -418 kJ / ( 4.18 kJ K-1 kg-1 x 100 kg ) = -418/418 = -1.0 K Note: Units are very important! Always attach units to each number and make sure they cancel to desired unit Problems you can do now (partially): 1b, 15, 16a,f, 19 3 A Detour into the Microscopic Realm pext Pressure of gas, p, is caused by enormous numbers of collisions on the walls of the container. -

Entropy Determination of Single-Phase High Entropy Alloys with Different Crystal Structures Over a Wide Temperature Range

entropy Article Entropy Determination of Single-Phase High Entropy Alloys with Different Crystal Structures over a Wide Temperature Range Sebastian Haas 1, Mike Mosbacher 1, Oleg N. Senkov 2 ID , Michael Feuerbacher 3, Jens Freudenberger 4,5 ID , Senol Gezgin 6, Rainer Völkl 1 and Uwe Glatzel 1,* ID 1 Metals and Alloys, University Bayreuth, 95447 Bayreuth, Germany; [email protected] (S.H.); [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (R.V.) 2 UES, Inc., 4401 Dayton-Xenia Rd., Dayton, OH 45432, USA; [email protected] 3 Institut für Mikrostrukturforschung, Forschungszentrum Jülich, 52425 Jülich, Germany; [email protected] 4 Leibniz Institute for Solid State and Materials Research Dresden (IFW Dresden), 01069 Dresden, Germany; [email protected] 5 TU Bergakademie Freiberg, Institut für Werkstoffwissenschaft, 09599 Freiberg, Germany 6 NETZSCH Group, Analyzing & Testing, 95100 Selb, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-921-55-5555 Received: 31 July 2018; Accepted: 20 August 2018; Published: 30 August 2018 Abstract: We determined the entropy of high entropy alloys by investigating single-crystalline nickel and five high entropy alloys: two fcc-alloys, two bcc-alloys and one hcp-alloy. Since the configurational entropy of these single-phase alloys differs from alloys using a base element, it is important to quantify ◦ the entropy. Using differential scanning calorimetry, cp-measurements are carried out from −170 C to the materials’ solidus temperatures TS. From these experiments, we determined the thermal entropy and compared it to the configurational entropy for each of the studied alloys. -

THERMOCHEMISTRY – 2 CALORIMETRY and HEATS of REACTION Dr

THERMOCHEMISTRY – 2 CALORIMETRY AND HEATS OF REACTION Dr. Sapna Gupta HEAT CAPACITY • Heat capacity is the amount of heat needed to raise the temperature of the sample of substance by one degree Celsius or Kelvin. q = CDt • Molar heat capacity: heat capacity of one mole of substance. • Specific Heat Capacity: Quantity of heat needed to raise the temperature of one gram of substance by one degree Celsius (or one Kelvin) at constant pressure. q = m s Dt (final-initial) • Measured using a calorimeter – it absorbed heat evolved or absorbed. Dr. Sapna Gupta/Thermochemistry-2-Calorimetry 2 EXAMPLES OF SP. HEAT CAPACITY The higher the number the higher the energy required to raise the temp. Dr. Sapna Gupta/Thermochemistry-2-Calorimetry 3 CALORIMETRY: EXAMPLE - 1 Example: A piece of zinc weighing 35.8 g was heated from 20.00°C to 28.00°C. How much heat was required? The specific heat of zinc is 0.388 J/(g°C). Solution m = 35.8 g s = 0.388 J/(g°C) Dt = 28.00°C – 20.00°C = 8.00°C q = m s Dt 0.388 J q 35.8 g 8.00C = 111J gC Dr. Sapna Gupta/Thermochemistry-2-Calorimetry 4 CALORIMETRY: EXAMPLE - 2 Example: Nitromethane, CH3NO2, an organic solvent burns in oxygen according to the following reaction: 3 3 1 CH3NO2(g) + /4O2(g) CO2(g) + /2H2O(l) + /2N2(g) You place 1.724 g of nitromethane in a calorimeter with oxygen and ignite it. The temperature of the calorimeter increases from 22.23°C to 28.81°C. -

Chapter 5. Calorimetiric Properties

Chapter 5. Calorimetiric Properties (1) Specific and molar heat capacities (2) Latent heats of crystallization or fusion A. Heat Capacity - The specific heat capacity is the heat which must be added per kg of a substance to raise the temperature by one degree 1. Specific heat capacity at const. Volume ∂U c = (J/kg· K) v ∂ T v 2. Specific heat capacity at cont. pressure ∂H c = (J/kg· K) p ∂ T p 3. molar heat capacity at constant volume Cv = Mcv (J/mol· K) 4. molar heat capacity at constat pressure ∂H C = M = (J/mol· K) p cp ∂ T p Where H is the enthalpy per mol ◦ Molar heat capacity of solid and liquid at 25℃ s l - Table 5.1 (p.111)에 각각 group 의 Cp (Satoh)와 Cp (Show)에 대한 data 를 나타내었다. l s - Table 5.2 (p.112,113)에 각 polymer 에 대한 Cp , Cp 값들을 나타내었다. - (Ex 5.1)에 polypropylene 의 Cp 를 구하는 것을 나타내었다. - ◦ Specific heat as a function of temperature - 그림 5.1 에 polypropylene 의 molar heat capacity 에 대한 그림을 나타 내었다. ◦ The slopes of the heat capacity for solid polymer dC s 1 p = × −3 s 3 10 C p (298) dt dC l 1 p = × −3 l 1.2 10 C p (298) dt l s (see Table 5.3) for slope of the Cp , Cp ◦ 식 (5.1)과 (5.2)에 온도에 따른 Cp 값 계산 (Ex) calculate the heat capacity of polypropylene with a degree of crystallinity of 30% at 25℃ (p.110) (sol) by the addition of group contributions (see table 5.1) s l Cp (298K) Cp (298K) ( -CH2- ) 25.35 30.4(from p.111) ( -CH- ) 15.6 20.95 ( -CH3 ) 30.9 36.9 71.9 88.3 ∴ Cp(298K) = 0.3 (71.9J/mol∙ K) + 0.7(88.3J/mol∙ K) = 83.3 (J/mol∙ K) - It is assumed that the semi crystalline polymer consists of an amorphous fraction l s with heat capacity Cp and a crystalline Cp P 116 Theoretical Background P 117 The increase of the specific heat capacity with temperature depends on an increase of the vibrational degrees of freedom. -

Module P7.4 Specific Heat, Latent Heat and Entropy

FLEXIBLE LEARNING APPROACH TO PHYSICS Module P7.4 Specific heat, latent heat and entropy 1 Opening items 4 PVT-surfaces and changes of phase 1.1 Module introduction 4.1 The critical point 1.2 Fast track questions 4.2 The triple point 1.3 Ready to study? 4.3 The Clausius–Clapeyron equation 2 Heating solids and liquids 5 Entropy and the second law of thermodynamics 2.1 Heat, work and internal energy 5.1 The second law of thermodynamics 2.2 Changes of temperature: specific heat 5.2 Entropy: a function of state 2.3 Changes of phase: latent heat 5.3 The principle of entropy increase 2.4 Measuring specific heats and latent heats 5.4 The irreversibility of nature 3 Heating gases 6 Closing items 3.1 Ideal gases 6.1 Module summary 3.2 Principal specific heats: monatomic ideal gases 6.2 Achievements 3.3 Principal specific heats: other gases 6.3 Exit test 3.4 Isothermal and adiabatic processes Exit module FLAP P7.4 Specific heat, latent heat and entropy COPYRIGHT © 1998 THE OPEN UNIVERSITY S570 V1.1 1 Opening items 1.1 Module introduction What happens when a substance is heated? Its temperature may rise; it may melt or evaporate; it may expand and do work1—1the net effect of the heating depends on the conditions under which the heating takes place. In this module we discuss the heating of solids, liquids and gases under a variety of conditions. We also look more generally at the problem of converting heat into useful work, and the related issue of the irreversibility of many natural processes. -

Atkins' Physical Chemistry

Statistical thermodynamics 2: 17 applications In this chapter we apply the concepts of statistical thermodynamics to the calculation of Fundamental relations chemically significant quantities. First, we establish the relations between thermodynamic 17.1 functions and partition functions. Next, we show that the molecular partition function can be The thermodynamic functions factorized into contributions from each mode of motion and establish the formulas for the 17.2 The molecular partition partition functions for translational, rotational, and vibrational modes of motion and the con- function tribution of electronic excitation. These contributions can be calculated from spectroscopic data. Finally, we turn to specific applications, which include the mean energies of modes of Using statistical motion, the heat capacities of substances, and residual entropies. In the final section, we thermodynamics see how to calculate the equilibrium constant of a reaction and through that calculation 17.3 Mean energies understand some of the molecular features that determine the magnitudes of equilibrium constants and their variation with temperature. 17.4 Heat capacities 17.5 Equations of state 17.6 Molecular interactions in A partition function is the bridge between thermodynamics, spectroscopy, and liquids quantum mechanics. Once it is known, a partition function can be used to calculate thermodynamic functions, heat capacities, entropies, and equilibrium constants. It 17.7 Residual entropies also sheds light on the significance of these properties. 17.8 Equilibrium constants Checklist of key ideas Fundamental relations Further reading Discussion questions In this section we see how to obtain any thermodynamic function once we know the Exercises partition function. Then we see how to calculate the molecular partition function, and Problems through that the thermodynamic functions, from spectroscopic data. -

Experimental Determination of Heat Capacities and Their Correlation with Theoretical Predictions Waqas Mahmood, Muhammad Sabieh Anwar, and Wasif Zia

Experimental determination of heat capacities and their correlation with theoretical predictions Waqas Mahmood, Muhammad Sabieh Anwar, and Wasif Zia Citation: Am. J. Phys. 79, 1099 (2011); doi: 10.1119/1.3625869 View online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1119/1.3625869 View Table of Contents: http://ajp.aapt.org/resource/1/AJPIAS/v79/i11 Published by the American Association of Physics Teachers Additional information on Am. J. Phys. Journal Homepage: http://ajp.aapt.org/ Journal Information: http://ajp.aapt.org/about/about_the_journal Top downloads: http://ajp.aapt.org/most_downloaded Information for Authors: http://ajp.dickinson.edu/Contributors/contGenInfo.html Downloaded 13 Aug 2013 to 157.92.4.6. Redistribution subject to AAPT license or copyright; see http://ajp.aapt.org/authors/copyright_permission Experimental determination of heat capacities and their correlation with theoretical predictions Waqas Mahmood, Muhammad Sabieh Anwar,a) and Wasif Zia School of Science and Engineering, Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), Opposite Sector U, D. H. A., Lahore 54792, Pakistan (Received 25 January 2011; accepted 23 July 2011) We discuss an experiment for determining the heat capacities of various solids based on a calorimetric approach where the solid vaporizes a measurable mass of liquid nitrogen. We demonstrate our technique for copper and aluminum, and compare our data with Einstein’s model of independent harmonic oscillators and the more accurate Debye model. We also illustrate an interesting material property, the Verwey transition -

Thermodynamic Temperature

Thermodynamic temperature Thermodynamic temperature is the absolute measure 1 Overview of temperature and is one of the principal parameters of thermodynamics. Temperature is a measure of the random submicroscopic Thermodynamic temperature is defined by the third law motions and vibrations of the particle constituents of of thermodynamics in which the theoretically lowest tem- matter. These motions comprise the internal energy of perature is the null or zero point. At this point, absolute a substance. More specifically, the thermodynamic tem- zero, the particle constituents of matter have minimal perature of any bulk quantity of matter is the measure motion and can become no colder.[1][2] In the quantum- of the average kinetic energy per classical (i.e., non- mechanical description, matter at absolute zero is in its quantum) degree of freedom of its constituent particles. ground state, which is its state of lowest energy. Thermo- “Translational motions” are almost always in the classical dynamic temperature is often also called absolute tem- regime. Translational motions are ordinary, whole-body perature, for two reasons: one, proposed by Kelvin, that movements in three-dimensional space in which particles it does not depend on the properties of a particular mate- move about and exchange energy in collisions. Figure 1 rial; two that it refers to an absolute zero according to the below shows translational motion in gases; Figure 4 be- properties of the ideal gas. low shows translational motion in solids. Thermodynamic temperature’s null point, absolute zero, is the temperature The International System of Units specifies a particular at which the particle constituents of matter are as close as scale for thermodynamic temperature. -

Molar Heat Capacity (Cv) for Saturated and Compressed Liquid and Vapor Nitrogen from 65 to 300 K at Pressures to 35 Mpa

Volume 96, Number 6, November-December 1991 Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology [J. Res. Nat!. Inst. Stand. Technol. 96, 725 (1991)] Molar Heat Capacity (Cv) for Saturated and Compressed Liquid and Vapor Nitrogen from 65 to 300 K at Pressures to 35 MPa Volume 96 Number 6 November-December 1991 J. W. Magee Molar heat capacities at constant vol- the Cv (fi,T) data and also show satis- ume (C,) for nitrogen have been mea- factory agreement with published heat National Institute of Standards sured with an automated adiabatic capacity data. The overall uncertainty and Technology, calorimeter. The temperatures ranged of the Cy values ranges from 2% in the Boulder, CO 80303 from 65 to 300 K, while pressures were vapor to 0.5% in the liquid. as high as 35 MPa. Calorimetric data were obtained for a total of 276 state Key words: calorimeter; heat capacity; conditions on 14 isochores. Extensive high pressure; isochorlc; liquid; mea- results which were obtained in the satu- surement; nitrogen; saturation; vapor. rated liquid region (C^^^' and C„) demonstrate the internal consistency of Accepted: August 30, 1991 Glossary ticular, the heat capacity at constant volume {Cv) is a,b,c,d,e Coefficients for Eq. (7) related to P(j^T) by: c. Molar heat capacity at constant volume a Molar heat capacity in the ideal gas state (1) C„<2> Molar heat capacity of a two-phase sample Jo a Molar heat capacity of a saturated liquid sample where C? is the ideal gas heat capacity. Conse- Vbamb Volume of the calorimeter containing sample quently, Cv measurements which cover a wide Vr, Molar volume, dm' • mol"' range of {P, p, T) states are beneficial to the devel- P Pressure, MPa opment of an accurate equation of state for the P.