Sir Charles Wilkins' Basic Contribution to Indology in the West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literatura Orientu W Piśmiennictwie Polskim XIX W

Recenzent dr hab. Kinga Paraskiewicz Projekt okładki Igor Stanisławski Na okładce wykorzystano fragment anonimowego obrazu w stylu kad żarskim „Kobieta trzymaj ąca diadem” (Iran, poł. XIX w.), ze zbiorów Państwowego Muzeum Ermita żu, nr kat. VP 1112 Ksi ąż ka finansowana w ramach programu Ministra Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wy ższego pod nazw ą „Narodowy Program Rozwoju Humanistyki” w latach 2013-2017 © Copyright by individual authors, 2016 ISBN 978-83-7638-926-4 KSI ĘGARNIA AKADEMICKA ul. św. Anny 6, 31-008 Kraków tel./faks 12-431-27-43, 12-421-13-87 e-mail: [email protected] Ksi ęgarnia internetowa www.akademicka.pl Spis tre ści Słowo wst ępne . 7 Ignacy Krasicki, O rymotwórstwie i rymotwórcach. Cz ęść dziewi ąta: o rymotwórcach wschodnich (fragmenty) . 9 § I. 11 § III. Pilpaj . 14 § IV. Ferduzy . 17 Assedy . 18 Saady . 20 Suzeni . 22 Katebi . 24 Hafiz . 26 § V. O rymotwórstwie chi ńskim . 27 Tou-fu . 30 Lipe . 31 Chaoyung . 32 Kien-Long . 34 Diwani Chod ża Hafyz Szirazi, zbiór poezji Chod ży Hafyza z Szyrazu, sławnego rymotwórcy perskiego przez Józefa S ękowskiego . 37 Wilhelm Münnich, O poezji perskiej . 63 Gazele perskiego poety Hafiza (wolny przekład z perskiego) przeło żył Jan Wiernikowski . 101 Józef Szujski, Rys dziejów pi śmiennictwa świata niechrze ścija ńskiego (fragmenty) . 115 Odczyt pierwszy: Świat ras niekaukaskich z Chinami na czele . 119 Odczyt drugi: Aryjczycy. Świat Hindusów. Wedy. Ksi ęgi Manu. Budaizm . 155 Odczyt trzeci: Epopeja indyjskie: Mahabharata i Ramajana . 183 Odczyt czwarty: Kalidasa i Dszajadewa [D źajadewa] . 211 Odczyt pi ąty: Aryjczycy. Lud Zendów – Zendawesta. Firduzi. Saadi. Hafis . 233 Piotr Chmielowski, Edward Grabowski, Obraz literatury powszechnej w streszczeniach i przekładach (fragmenty) . -

1 Title: Enlightenment and Empire, Mughals and Marathas: The

Title: Enlightenment and Empire, Mughals and Marathas: The Religious History of Indian in the Work of East India Company Servant, Alexander Dow. Abstract: This article situates the work of East India Company servant Alexander Dow (1735-1779), principally his writings on the history and future state of India, in contemporary debates about empire, religion and enlightened government. To do so it offers a sustained analysis of his 1772 essay “A Dissertation Concerning the Origin and Nature of Despotism in Hindostan”, as well as his proposals for the restoration of Bengal, both of which played an influential part in shaping the preoccupations with Mughal history that dominated the contemporary crisis in the Company’s legitimacy. By linking these texts to his earlier work on ‘Hindoo’ religion, it will argue that Dow’s analysis of the relationship between certain religious cultures and their civic qualities was rooted in a deist perspective. It doing so it restores the enlightenment components of Dow’s thought, and their impact on the ideology of empire, in a crucial period of British expansion in India. Keywords: Empire, Enlightenment, India, Eighteenth Century, East India Company, Religion 1 Historians are increasingly concerned with the Enlightenment’s extra-European context.1 In particular, recognising that international commerce and exchange were its material context, scholars have turned their attention to Enlightenment attitudes to empire. For Sankar Muthu this has meant tracing anti-imperialist strands of enlightenment thought.2 This -

The Upanishads, Vol I

The Upanishads, Vol I Translated by F. Max Müller The Upanishads, Vol I Table of Contents The Upanishads, Vol I........................................................................................................................................1 Translated by F. Max Müller...................................................................................................................1 PREFACE................................................................................................................................................7 PROGRAM OF A TRANSLATION...............................................................................................................19 THE SACRED BOOKS OF THE EAST........................................................................................................20 TRANSLITERATION OF ORIENTAL ALPHABETS,..............................................................................25 INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................26 POSITION OF THE UPANISHADS IN VEDIC LITERATURE.......................................................30 DIFFERENT CLASSES OF UPANISHADS.......................................................................................31 CRITICAL TREATMENT OF THE TEXT OF THE UPANISHADS................................................33 MEANING OF THE WORD UPANISHAD........................................................................................38 WORKS ON THE UPANISHADS....................................................................................................................41 -

Aesthetics, Subjectivity, and Classical Sanskrit Women Poets

Voices from the Margins: Aesthetics, Subjectivity, and Classical Sanskrit Women Poets by Kathryn Marie Sloane Geddes B.A., The University of British Columbia, 2016 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2018 © Kathryn Marie Sloane Geddes 2018 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, a thesis/dissertation entitled: Voices from the Margins: Aesthetics, Subjectivity, and Classical Sanskrit Women Poets submitted by Kathryn Marie Sloane Geddes in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Asian Studies Examining Committee: Adheesh Sathaye, Asian Studies Supervisor Thomas Hunter, Asian Studies Supervisory Committee Member Anne Murphy, Asian Studies Supervisory Committee Member Additional Examiner ii Abstract In this thesis, I discuss classical Sanskrit women poets and propose an alternative reading of two specific women’s works as a way to complicate current readings of Classical Sanskrit women’s poetry. I begin by situating my work in current scholarship on Classical Sanskrit women poets which discusses women’s works collectively and sees women’s work as writing with alternative literary aesthetics. Through a close reading of two women poets (c. 400 CE-900 CE) who are often linked, I will show how these women were both writing for a courtly, educated audience and argue that they have different authorial voices. In my analysis, I pay close attention to subjectivity and style, employing the frameworks of Sanskrit aesthetic theory and Classical Sanskrit literary conventions in my close readings. -

Mitrasamprapthi Preliminary

i ^GÈ8ZHB ^GD^09 QP9·¦R ^B¦J¿ºP^»f ¥ª¶»|§¶¤¶»Æ ¥¶D˶ ¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¶ )¶X¶À» ˶Ç˶ ¥»Ë¶¶Ç· 2·Ç¦~º»À¥»¶Td¶Ç¶}˶·ª·¶U¶ ¶Ç·¶2¶¶» X· #˶ X· 2À$d 2¶»¤¶»»¶¤¶¢£ ¶··Ç9¶ ÀÇ9¶³¶½¶»2ÀºÇ¶¥§¶¦¥· » ÀÇQ¡d2·¡ÀºI»$¤¶¶^ÀÇ9¶³¶½¶» ii Blank iii ¤¶»»¶»Y ÀÇ9¶³¶½¶» 2ÀºÇ¶ ¥§¶¦¥· »¶ ¶Ç¶}˶ #¶»¶ ¤¶»ÇX¶´»» )¶X¶Àº À¥»¶Td 2·Ç ¶¶¥ ˶¶9¶~» ¶Ç¶}˶ ¥·Æ9¶´9À¥ª¶»|§¶¤¶»Æ¥¶D˶¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¶·9¶¤¶¶»¶U¶¤¶·: 9¶¶Y®À ·¶~º» ¶Ç¶}~» ¶J·P¶ °·9¶½ ¤¶¸¶¥º» ¤¶¿Â 9¶³¶¶C¶»2À4¶Ç¶}˶·ª·¶»¶#˶¤¶§¶2¶¤·:À ¥ª¶»|§¶¤¶»Æ ¥¶D˶ ¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¶ ¥»Ë¶¶Ç·» & ¶U¶¤¶¶» #·¶2¶ °·9¶½ ¥·Æ¤¶ÄǶ2À4 #¶»2¶½ ¤·9¶»¤¶ º~»¢£ ¶2· 2À4®¶y¶Y®2À½QTX·#˶°·9¶½X·2À$d2¶»¤¶»»¶¤¶¢£ #¤¶9À¶¶¤·¶9¶³¶» ¶Ç¶}˶ #·¶2¶¶» °·9¶½ ¥·Æ9¶³¶» & 2¶Ä~»¶» ¶¶»¶½º9¶¶XÀ»»¤¶ÀǶ»$¨¶»ËÀºÀ À¾vJ·ÀRd '¶2¶» ¶~9¶³¶» ÀÇ9¶³¶½¶»2ÀºÇ¶¥§¶¦¥· » ÀÇ9¶³¶½¶» iv Blank v ¶Ç·¶2¶¶¶»Y ¶Ç¶}˶ ·±Ë¶ ¶2·¶9¶³¶¢£ ,Ç·¶ 2¶··±Ë¶¤¶¼ ¥§¶¦¶®¶y¤·¶»¶»%Ç˶°¶·±Ë¶¶#¶»¶¤¶¼%Ç9¶½#˶Ç˶ ¶¶»Ë¶¤·:À & 2¶··±Ë¶ 9¶Ç¶9¶³¶¢£ ¶¤¶»»5¤·¶ ,Ƕ» 2¶Ä~ ¥ª¶»|§¶¤¶»Æ¥¶D˶¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶vÀÇ9¶³¶½¶»2ÀºÇ¶¥§¶¦¥· »¶ ¶Ç¶}˶ #¶»¶ ¤¶»ÇX¶´»» Àº §ÀÁ2¶¬`2¶ ¤¶ª¶ÆǶ J·9À z¶»¤¶ÇËÀ ¦~º» À¥»¶Td 2·Ç ˶¶9¶~9À ¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¶ ¥»Ë¶¶Ç·» ,Ƕ» ·9¶¤¶¶» ¶U¶¤¶·: 9¶¶Y®Ë¶» %¶¶ ¶Ç·¶·2·»Æ¤¶¶»¶¤¶»9À¤¶±®Ë¶»¤¶»ÇX¶´»¶½C¶À»ÇËÀ #·¶2¶¶» °·9¶½ ¥·Æ9¶´9À #¶»2¶½ ¤·9¶»¤¶ º~»¢£ & ¶U¶¤¶¶»®¶y¶Y¶¡·:À ¤¶»½ ¶Ç¶}˶ ¶U¶·9¶¤¶¶» 2¶Äª¶|·¶ #2·X¶¥» ¤·¶1·® ¶2¶Q¶Y®¶»¤¶X·¶»·2¶¶¤¶¸ ¥º»%¤¶¶¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¤¶¿d )Çz2¶Ä~»Ç¶®¦º2¶¶¡·:À &¶U¶2À4JÀ¶£¨Ç9d°ÂdÀ°¶¢X·¶¥ºd2¶»¤¶¸d ¶M¸ ¤¶»Ë¶» X· #ÇI· %¤¶¶ ¶ÇC¶Ë¶Ç˶¤¶¿d ¶¼¶2¶¶ $Ç9¶£ #¶»¤·¶¤¶¶» »·¤¶Ë·: ®¦º2¶¶¡·:À & ¶U¶¶¼¶2¶¶ ¶C¶À»¢£ #Àº2¶ 2¶Ä~9¶³¶ ¶°·»¤¶¶» ¶XÀ»¡·:À & )¡·£ 9¶Ç¶2¶Ë¶ÄÆ9¶´9¶½·¤¶¼$·¸:¶»ËÀº¤À & ¶U¶¶ 2¶¶X¶ -

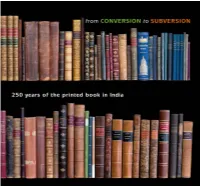

From Conversion to Subversion a Selection.Pdf

2014 FROM CONVERSION TO SUBVERSION: 250 years of the printed book in India 2014 From Conversion to Subversion: 250 years of the printed book in India. A catalogue by Graham Shaw and John Randall ©Graham Shaw and John Randall Produced and published in 2014 by John Randall (Books of Asia) G26, Atlas Business Park, Rye, East Sussex TN31 7TE, UK. Email: [email protected] All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior permission in writing of the publisher and copyright holder. Designed by [email protected], Devon Printed and bound by Healeys Print Group, Suffolk FROM CONVERSION TO SUBVERSION: 250 years of the printed book in India his catalogue features 125 works spanning While printing in southern India in the 18th the history of print in India and exemplify- century was almost exclusively Christian and Ting the vast range of published material produced evangelical, the first book to be printed in over 250 years. northern India was Halhed’s A Grammar of the The western technology of printing with Bengal Language (3), a product of the East India movable metal types was introduced into India Company’s Press at Hooghly in 1778. Thus by the Portuguese as early as 1556 and used inter- began a fertile period for publishing, fostered mittently until the late 17th century. The initial by Governor-General Warren Hastings and led output was meagre, the subject matter over- by Sir William Jones and his generation of great whelmingly religious, and distribution confined orientalists, who produced a number of superb to Portuguese enclaves. -

Article (176.8Kb)

garcin de tassy Origin and Diffusion of Hindustani [translator’s note: Presented here is the translation of a memorandum entitled ìOrigine et Diffusion de líHindoustani Appelé Language Générale ou Nationale de líIndeî (Origin and Diffusion of Hindustani, Called the Common or National Language of India) by Garcin de Tassy (1871) published in the transactions of the Royal Academy of Science, Arts, and Belles-Lettres of Caen, France. Written in the last decade of his life, this brief memorandum contains some of his observations and conclusions based on over half a century of involvement with Indian languagesóespecially Urdu, which was gener- ally called Hindustani during his time. Most of his peer academy members, to whom this communication was directed, probably did not know much about Urdu. Consequently, he includes some explanations and background information that would seem too elementary nowadays. Nevertheless, some of his remarks still seem fresh and surprising. Even his digressionary remarks, which are dispersed throughout the note and which often seem factitious, contain much information about the historical and cultural factors influencing the development of Urdu. The note also reveals de Tassyís passionate at- tachment to Urdu and his angst over the Urdu-Hindi controversy which, he thought, was going to lead to disastrous religious and political strife in India.] We can only make conjectures about the exact dates of Indiaís invasion by the Aryans and the diffusion of their language; the language was called Sanskrit (well-formed), in contrast to the language of the natives and its various dialects that were together given the name Prakrit (ill-formed) by the scornful victors. -

Subject: EVOLUTION of SOCIAL STRUCTURE in INDIA: THROUGH the AGES Credits: 4 SYLLABUS

Subject: EVOLUTION OF SOCIAL STRUCTURE IN INDIA: THROUGH THE AGES Credits: 4 SYLLABUS Introductory & Cultures in Transition Harappan Civilisation and other Chalcolithic Cultures, Hunting-Gathering, Early Farming Society, Pastoralism, Reconstructing Ancient Society with Special Reference to Sources, Emergence of Buddhist Central And Peninsular India, Socio-Religious Ferment In North India: Buddhism And Jainism, Iron Age Cultures, Societies Represented In Vedic Literature Early Medieval Societies & Early Historic Societies: 6th Century - 4th Century A.D Religion in Society, Proliferation and consolidation of Castes and Jatis, The Problem of Urban Decline: Agrarian Expansion, Land Grants and Growth of Intermediaries, Transition To Early Medieval Societies, Marriage and Family Life,Notions of Untouchability, Changing Patterns in Varna and Jati, Early Tamil Society –Regions and Their Cultures and Cult of Hero Worship, Chaityas, Viharas and Their Interaction with Tribal Groups, Urban Classes: Traders and Artisans, Extension of Agricultural Settlements Medieval Society & Society on the Eve of Colonialism Rural Society: Peninsular India, Rural Society: North India, Village Community, The Eighteenth Century Society in Transition, Socio Religious Movements, Changing Social Structure in Peninsular India, Urban Social Groups in North India, Modern Society & Social Questions under Colonialism Social Structure in The Urban and Rural Areas, Pattern of Rural-Urban Mobility: Overseas Migration, Studying Castes in The New Historical Context, Perceptions of The Indian Social Structure by The Nationalists and Social Reformers, Clans and Confederacies in Western India, Studying Tribes Under Colonialism, Popular Protests and Social Structures, Social Discrimination, Gender/Women Under Colonialism, Colonial Forest Policies and Criminal Tribes Suggested Reading: 1. Nation, Nationalism and Social Structure in Ancient India : Shiva Acharya 2. -

List of Books Available on Calibre Software

LIST OF BOOKS AVAILABLE ON CALIBRE SOFTWARE (PLEASE CONTACT LIBRARY STAFF TO ACCESS CALIBRE) 1. 1.doc · Kamal Swaroop 2. 50 Volume RGS Journal Table of Contents s · Unknown 3. 1836 Asiatic Researches Vol 19 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 4. 1839 Asiatic Researches Vol 19 Part 2 : THE HISTORY, THE ANTIQUITIES, THE ARTS AND SCIENCES, AND LITERATURE ASIA . · Asiatic Society, Calcutta 5. 1839 Asiatic Researches Vol 19 Part 2 s+m · Unknown 6. 1840 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 8 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 7. 1840 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 8 Part 2 s+m · Unknown 8. 1840 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 9 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 9. 1856 JASB Index AR 19 to JASB 23 · Unknown 10. 1856 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 24 s+m · Unknown 11. 1862 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 30 s+m · Unknown 12. 1866 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 34 s+m · Unknown 13. 1867 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 35 s+m · Unknown 14. 1875 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 44 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 15. 1875 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 44 Part 2 s+m · Unknown 16. 1951-52.PMD · Unknown 17. 1952-53-(Final).PMD · Unknown 18. 1953-54.pmd · Unknown 19. 1954-55.pmd · Unknown 20. 1955-56.pmd · Unknown 21. 1956-57.pmd · Unknown 22. 1957-58(interim) 1957-58-1958-59 · Unknown 23. 62569973-Text-of-Justice-Soumitra-Sen-s-Defence · Unknown 24. ([Views of the East; Comprising] India, Canton, [And the Shores of the Red Sea · Robert Elliot 25. -

Catalogue of Bengali Printed Books in the Library of the British Museum. By

- ' - .. ' - ^ - . - -- n $m . \ *<H >r, t&OHC*tU> V>IV\T \soafe*. tx ISi, -s^ A SUPPLEMENTAEY CATALOGUE OF BENGALI BOOKS\ IN THB LIBRARY OP THE BRITISH MUSEUM ACQrii:Ki> THK YK.*I;S i886-r.m. COMPILED BY J. F. BLrMHARDT, MA. AJO> OJC BIXDI OF HMDCITAXI, UUTCkB* AXD MKOALI AT CKTrKKSITT COIXEOI, LONDON ; AJTD TCACBBB Of CHUALI AT TIB CNIVBUtTT OF OXFORD. PRINTED BY ORDER OF THE TRUSTEES lonDon : SOLD AT TUB BRITISH MUSEUM; Ar> IT Ac CO.. 39, PATKRXoerai Row; BERNARD QUARITCH, 11, GRAFTO* STRBKT, Niw BOXD W. ; A8HER & BiDromo STBKT, CO., 14, STRMT, Cornrr GAEDKN ; AHD 1IKNRY FROWDE, OXFORD UKIYKMITT PKIM WARKBOUBI, AMEN CORNBR. 1910 [AU rigklt LONDON: PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED, PUKE STREET, STAMFORD STREET, S.E., AXD GREAT WINDMILL STRKET, W. PREFACE. THIS Catalogue of the Bengali Printed Books acquired by the Library of tli- I>riti>h Museum during the years 18861910 has been prepared by Mr. Bliimlmnlt as a supple- of ment to the volume compiled l<y him and published by order the Trustees in 1886. In the present catalogue a classified index of titles has been added; in other respects the methods employed in the earlier volume have been closely followed in this work. I. 1'. BARNETT. ' r cf Ori> "''I/ I'rin-- /.' nut .I/NX. ,i-ii MI-KIM, 1910. AUTHOE'S PEEFACE. THIS Catalogue of Bengali liooks acquired during the last 24 years forms a supplement to the Bengali Catalogue published in 1886. It has been prepared on the .same principle-;, and with the same system of transliteration. -

A Cymmrodor Claims Kin in Calcutta: an Assessment of Sir William Jones As Philologer, Polymath, and Pluralist

Chap 004_Kin in Calcutta 2/8/05 9:21 am Page 50 A Cymmrodor claims kin in Calcutta: an assessment of Sir William Jones as philologer, polymath, and pluralist by Garland Cannon and Michael J. Franklin* It was a custom among the Ancient Britons (and still retained in Anglesey) for the most knowing among them in the descent of families, to send their friends of the same stock or family, a dydd calan Ionawr a calennig, [New Year’s gift] a present of their pedigree; [...] [T]he very thought of those brave people, who struggled so long with a superior power for their liberty, inspires me with such an idea of them, that I almost adore their memories.1 This genealogical present, of inherent interest to all the ‘earliest natives’ [Cymmrodorion] of Wales and beyond, was sent in a letter of New Year’s Day 1748 by the ‘learned British antiquary’ and co-founder of this society, Lewis Morris (1701-65) to his friend William ap Sion Siors (son of John George), known in London as William Jones, FRS (c.1675-1749), ‘Longitude Jones’, celebrated mathematician, disseminator of Newtonian theory, and father of the future Orientalist.2 This document, now sadly lost, showed that the Morrises and the Joneses were closely related, sharing an ancestry deriving from Hwfa ap Cynddelw and the princes of Gwynedd. Exactly why a seemingly insignificant Ynys Môn parish should produce within two generations a scholar of the calibre of William Jones sen. and polymaths of such importance as Lewis Morris and Sir William Jones remains something of a mystery.3 This new study of Jones the linguist and literary * The authors would like to express their gratitude to Professor Hal W. -

Life-Writing and Colonial Relations, 1794-1826 a Dissertation

Creating Indian and British Selves: Life-Writing and Colonial Relations, 1794-1826 A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Charlotte Madere IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Brian Goldberg April 2020 © Charlotte Ellen Madere, 2020 i Acknowledgements At the University of Minnesota, my advising committee has provided tremendous support to me throughout the dissertation process. I thank Brian Goldberg, my advisor, for encouraging my growth as both a scholar and a teacher. He offered detailed feedback on numerous chapter drafts, and I am so grateful for his generosity and thoughtfulness as a mentor. Andrew Elfenbein helped to shape my project by encouraging my interest in colonial philology and the study of Indian languages. Through her feedback, Amit Yahav enriched my understanding of the formal complexities of fiction and philosophical writings from the long eighteenth century. Nida Sajid’s comments spurred me to deepen my engagement with the fields of South Asian studies and postcolonial theory. I am deeply grateful to my entire committee for their engaged, rigorous guidance. Various professors at Trinity College, Dublin, nurtured my scholarly development during my undergraduate career. Anne Markey, my thesis advisor, helped me to build expertise in British and Irish writings from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. I am grateful, too, to Darryl Jones for expanding my knowledge of that era’s popular literature. I thank my advisor, Philip Coleman, for encouraging me to pursue graduate studies at the University of Minnesota. Support from the University of Minnesota’s English department enabled me to complete vital research for my dissertation.