The Evolution of the Printed Bengali Character

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traditional Bengali Keyboar

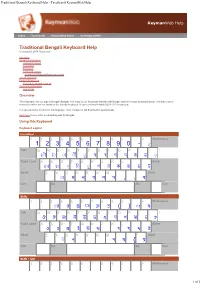

Traditional Bengali Keyboard Help - Tavultesoft KeymanWeb Help Keyman Web Help Index Tavultesoft KeymanWeb Demo Get KeymanWeb Traditional Bengali Keyboard Help Keyboard © 2008 Tavultesoft Overview Using this Keyboard Keyboard Layout Quickstart Examples Keyboard Details Complete Keyboard Reference Chart Troubleshooting Further Resources Related Keyboard Layouts Technical Information Authorship Overview This keyboard lets you type in Bengali (Bangla). It is easy to use for people familiar with Bengali and the Inscript keyboard layout. It includes some characters which are not found on the Inscript keyboard. It uses a normal English (QWERTY) keyboard. If a special font is needed for this language, most computers will download it automatically. Click here to see other keyboard layouts for Bengali. Using this Keyboard Keyboard Layout Unshifted ` 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 - = Backspace 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 - ◌ Tab Q W E R T Y U I O P [ ] \ ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ Caps Lock A S D F G H J K L ; ' Enter ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ Shift Z X C V B N M , . / Shift ◌ , . Ctrl Alt Alt Ctrl Shift ` 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 - = Backspace ◌ !" # $ ( ) ◌% & Tab Q W E R T Y U I O P [ ] \ ' ( ) * + , - . / 0 1 2 Caps Lock A S D F G H J K L ; ' Enter 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 : ; < Shift Z X C V B N M , . / Shift ◌= > ? " { @ Ctrl Alt Alt Ctrl Shift + Ctrl ` 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 - = Backspace 1 of 5 Traditional Bengali Keyboard Help - Tavultesoft KeymanWeb Help Tab Q W E R T Y U I O P [ ] \ Caps Lock A S D F G H J K L ; ' Enter Shift Z X C V B N M , . -

75 Characters Maximum

Kannada Script LGR Proposal Introduction, Current Analysis and Next Steps Dr. U.B. Pavanaja NBGP F2F Meeting, Colombo 14 December 2017 | 1 Agenda 1 2 3 Introduction to Repertoire Analysis Within Script Kannada Script Variants 4 5 6 Cross-Script WLE Rules Current Status and Variants Next Steps for Completion | 2 Introduction to Kannada Script Population – there are about 60 million speakers of Kannada language which uses Kannada script. Geographical area - Kannada is spoken predominantly by the people of Karnataka State of India. It is also spoken by significant linguistic minorities in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Kerala, Goa and abroad Languages written in Kannada script – Kannada, Tulu, Kodava (Coorgi), Konkani, Havyaka, Sanketi, Beary (byaari), Arebaase, Koraga | 3 Classification of Characters Swaras (vowels) Letter ಅ ಆ ಇ ಈ ಉ ಊ ಋ ಎ ಏ ಐ ಒ ಓ ಔ Vowel sign/ N/Aಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ ಾ matra Yogavahas In Kannada, all consonants Anusvara ಅಂ (vyanjanas) when written as ಕ (ka), ಖ (kha), ಗ (ga), etc. actually have a built-in vowel sign (matra) Visarga ಅಃ of vowel ಅ (a) in them. | 4 Classification of Characters Vargeeya vyanjana (structured consonants) voiceless voiceless aspirate voiced voiced aspirate nasal Velars ಕ ಖ ಗ ಘ ಙ Palatals ಚ ಛ ಜ ಝ ಞ Retroflex ಟ ಠ ಡ ಢ ಣ Dentals ತ ಥ ದ ಧ ನ Labials ಪ ಫ ಬ ಭ ಮ Avargeeya vyanjana (unstructured consonants) ಯ ರ ಱ (obsolete) ಲ ವ ಶ ಷ ಸ ಹ ಳ ೞ (obsolete) | 5 Repertoire Included-1 Sr. Unicode Glyph Character Name Unicode Indic Ref Widespread No. Code General Syllabic use ? Point Category Category [Yes/No] 1 0C82 ಂ KANNADA SIGN ANUSVARA Mc Anusvara Yes 2 0C83 ಂ KANNADA SIGN VISARGA Mc Visarga Yes 3 0C85 ಅ KANNADA LETTER A Lo Vowel Yes 4 0C86 ಆ KANNADA LETTER AA Lo Vowel Yes 5 0C87 ಇ KANNADA LETTER I Lo Vowel Yes 6 0C88 ಈ KANNADA LETTER II Lo Vowel Yes 7 0C89 ಉ KANNADA LETTER U Lo Vowel Yes 8 0C8A ಊ KANNADA LETTER UU Lo Vowel Yes KANNADA LETTER VOCALIC 9 0C8B ಋ R Lo Vowel Yes 10 0C8E ಎ KANNADA LETTER E Lo Vowel Yes | 6 Repertoire Included-2 Sr. -

Literatura Orientu W Piśmiennictwie Polskim XIX W

Recenzent dr hab. Kinga Paraskiewicz Projekt okładki Igor Stanisławski Na okładce wykorzystano fragment anonimowego obrazu w stylu kad żarskim „Kobieta trzymaj ąca diadem” (Iran, poł. XIX w.), ze zbiorów Państwowego Muzeum Ermita żu, nr kat. VP 1112 Ksi ąż ka finansowana w ramach programu Ministra Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wy ższego pod nazw ą „Narodowy Program Rozwoju Humanistyki” w latach 2013-2017 © Copyright by individual authors, 2016 ISBN 978-83-7638-926-4 KSI ĘGARNIA AKADEMICKA ul. św. Anny 6, 31-008 Kraków tel./faks 12-431-27-43, 12-421-13-87 e-mail: [email protected] Ksi ęgarnia internetowa www.akademicka.pl Spis tre ści Słowo wst ępne . 7 Ignacy Krasicki, O rymotwórstwie i rymotwórcach. Cz ęść dziewi ąta: o rymotwórcach wschodnich (fragmenty) . 9 § I. 11 § III. Pilpaj . 14 § IV. Ferduzy . 17 Assedy . 18 Saady . 20 Suzeni . 22 Katebi . 24 Hafiz . 26 § V. O rymotwórstwie chi ńskim . 27 Tou-fu . 30 Lipe . 31 Chaoyung . 32 Kien-Long . 34 Diwani Chod ża Hafyz Szirazi, zbiór poezji Chod ży Hafyza z Szyrazu, sławnego rymotwórcy perskiego przez Józefa S ękowskiego . 37 Wilhelm Münnich, O poezji perskiej . 63 Gazele perskiego poety Hafiza (wolny przekład z perskiego) przeło żył Jan Wiernikowski . 101 Józef Szujski, Rys dziejów pi śmiennictwa świata niechrze ścija ńskiego (fragmenty) . 115 Odczyt pierwszy: Świat ras niekaukaskich z Chinami na czele . 119 Odczyt drugi: Aryjczycy. Świat Hindusów. Wedy. Ksi ęgi Manu. Budaizm . 155 Odczyt trzeci: Epopeja indyjskie: Mahabharata i Ramajana . 183 Odczyt czwarty: Kalidasa i Dszajadewa [D źajadewa] . 211 Odczyt pi ąty: Aryjczycy. Lud Zendów – Zendawesta. Firduzi. Saadi. Hafis . 233 Piotr Chmielowski, Edward Grabowski, Obraz literatury powszechnej w streszczeniach i przekładach (fragmenty) . -

Cross-Cultural Research

Cross-Cultural Research http://ccr.sagepub.com Cultural Adaptations After Progressionism Lauren W. McCall Cross-Cultural Research 2009; 43; 62 DOI: 10.1177/1069397108328613 The online version of this article can be found at: http://ccr.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/43/1/62 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: Society for Cross-Cultural Research Additional services and information for Cross-Cultural Research can be found at: Email Alerts: http://ccr.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://ccr.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations http://ccr.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/43/1/62 Downloaded from http://ccr.sagepub.com at DUKE UNIV on January 9, 2009 Cross-Cultural Research Volume 43 Number 1 February 2009 62-85 © 2009 Sage Publications Cultural Adaptations After 10.1177/1069397108328613 http://ccr.sagepub.com hosted at Progressionism http://online.sagepub.com Lauren W. McCall National Evolutionary Synthesis Center How should behavioral scientists interpret apparently progressive stages of cultural history? Adaptive progress in biology is thought to only occur locally, relative to local conditions. Just as evolutionary theory offers physi- cal anthropologists an appreciation of global human diversity through local adaptation, so the metaphor of adaptation offers behavioral scientists an appreciation of cultural diversity through analogous mechanisms. Analyses reported here test for cultural adaptation in both biotic and abiotic environ- ments. Testing cultural adaptation to the human-made environment, the culture’s pre-existing technical complexity is shown to be a predictive fac- tor. Then testing cultural adaptation to the physical environment, this article corroborates Divale’s (1999) finding that counting systems are adaptations to unstable environments, and expands the model to include other environ- mental indices and cultural traits. -

A Dictionary of Typography and Its Accessory Arts. Presented to the Subscribers of the "Printers' Register," 1870

: Supplement to tin- "^rtnters 1 Register," September vt, mdccclxxi. "*>. > % V V .. X > X V X V * X X V s X X X V S X S X V X X S X X V X .X X X\x X X .X X X N .N .X X S A t. y littimrarg uprjrajjlur i f / / 4 / / / AND / I '/ ITS ACCESSORY ARTS /• - I / / i 7 ': BY / / I /; r JOHN SOUTHWARD. / /. / / / i ^rescntcb to the Subscribers of the "^printers' T^cgistcr. 1870-1871. / n V / gonfcon JOSEPH M. POWELL, "PRINTERS' REGISTER" OFFICE, 3, BOUVERIE STREET, E.( . / PRINTED 9Y DANIEL & CO., ST. LEONARDS-ON-SEA j — 2? 113 %\%\ of JutjiOUtlCS. Among the various works on the Art of Printing, consulted in the compilation ol this Dictionary, may be named the following : Abridgments of Specifications relating to Printing. Johnson's Typographia. Andrews's History of British Journalism. Knight's Caxton. Annales de la Typographic Francaise et etrangere. Knight's Knowledge is Powei Annales de ITmprimerie. knight's Old Printer and the Modern Pres> xviii. Annals of Our Time. London Encyclopedia. Printing— vol. p , Annuaire de la Librairie et de ITmprimerie. Mi' {Cellar's American Printer. Cabbage's Economy of Machinery and Manufactures. Marahren's Handbuch der Typographic Bullhorn's Grammatography. Maverick's Henry J. Raymund and the New York IV---. Beadnell's Guide to Typography. McCreery's Press, a Poem. Biographical Memoirs of William (Jed. Morgan's Dictionary of Terms u.sed in Printing. Buckingham's Personal Memoirs and Recollections of Editorial Life. Moxon's Mechanick Exercis Buckingham's Specimens of Newspaper Literature. -

Handwriting Recognition in Indian Regional Scripts: a Survey of Offline Techniques

1 Handwriting Recognition in Indian Regional Scripts: A Survey of Offline Techniques UMAPADA PAL, Indian Statistical Institute RAMACHANDRAN JAYADEVAN, Pune Institute of Computer Technology NABIN SHARMA, Indian Statistical Institute Offline handwriting recognition in Indian regional scripts is an interesting area of research as almost 460 million people in India use regional scripts. The nine major Indian regional scripts are Bangla (for Bengali and Assamese languages), Gujarati, Kannada, Malayalam, Oriya, Gurumukhi (for Punjabi lan- guage), Tamil, Telugu, and Nastaliq (for Urdu language). A state-of-the-art survey about the techniques available in the area of offline handwriting recognition (OHR) in Indian regional scripts will be of a great aid to the researchers in the subcontinent and hence a sincere attempt is made in this article to discuss the advancements reported in this regard during the last few decades. The survey is organized into different sections. A brief introduction is given initially about automatic recognition of handwriting and official re- gional scripts in India. The nine regional scripts are then categorized into four subgroups based on their similarity and evolution information. The first group contains Bangla, Oriya, Gujarati and Gurumukhi scripts. The second group contains Kannada and Telugu scripts and the third group contains Tamil and Malayalam scripts. The fourth group contains only Nastaliq script (Perso-Arabic script for Urdu), which is not an Indo-Aryan script. Various feature extraction and classification techniques associated with the offline handwriting recognition of the regional scripts are discussed in this survey. As it is important to identify the script before the recognition step, a section is dedicated to handwritten script identification techniques. -

Introduction to Printing Technologies

Edited with the trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor To remove this notice, visit: www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping Introduction to Printing Technologies Study Material for Students : Introduction to Printing Technologies CAREER OPPORTUNITIES IN MEDIA WORLD Mass communication and Journalism is institutionalized and source specific. Itfunctions through well-organized professionals and has an ever increasing interlace. Mass media has a global availability and it has converted the whole world in to a global village. A qualified journalism professional can take up a job of educating, entertaining, informing, persuading, interpreting, and guiding. Working in print media offers the opportunities to be a news reporter, news presenter, an editor, a feature writer, a photojournalist, etc. Electronic media offers great opportunities of being a news reporter, news editor, newsreader, programme host, interviewer, cameraman,Edited with theproducer, trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor director, etc. To remove this notice, visit: www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping Other titles of Mass Communication and Journalism professionals are script writer, production assistant, technical director, floor manager, lighting director, scenic director, coordinator, creative director, advertiser, media planner, media consultant, public relation officer, counselor, front office executive, event manager and others. 2 : Introduction to Printing Technologies INTRODUCTION The book introduces the students to fundamentals of printing. Today printing technology is a part of our everyday life. It is all around us. T h e history and origin of printing technology are also discussed in the book. Students of mass communication will also learn about t h e different types of printing and typography in this book. The book will also make a comparison between Traditional Printing Vs Modern Typography. -

Why Dots and Dashes Matter: Writing Bengali in Roman Script Colonial Contexts, of Non-Roman Scripts Generally, Except for Greek

Carmen Brandt Why Dots and Dashes Matter Writing Bengali in Roman Script A friend recently sent me a photo of an Indian restaurant called “Vagina Tandoori” and asked for my ‘official statement’ as a scholar of South Asian studies. After we had had a good laugh – as many other Internet users had before us – I was not shy of providing an answer, as I explained the potential reason behind this awkward name: the restaurant owners could be of Bengali origin and might have transcribed the Bengali term ভািগনা/bhāginā1 “nephew”2, the way they thought it should be written in Roman script. I have come across this transcription several times in Bangladesh. Beyond that, a male colleague of mine regularly gets emails from his “vagina”, i.e. from a friend in Bangla- desh who is much younger to him and refers to himself as his “nephew”. Even though the awkward restaurant name turned out to be a hoax,3 the writing of South Asian lan- guages – especially Bengali – in Roman script is, nonetheless, often a challenge. Hence, this essay reflects on these challenges, discusses in general why South Asian languages are often written in Roman script, and which options might be best to do so. The Roman Script – a Symbol of Colonial Conquest As I have already discussed in detail (Brandt 2020), in South Asia, the Roman script is often perceived as a symbol of foreign domination in past and present. Its 1 All Bengali words are transliterated according to the rules in Table 4 below. 2 That means the son of one’s sister or the son of one’s husband’s sister. -

Proposal for a Kannada Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR)

Proposal for a Kannada Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR) Proposal for a Kannada Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR) LGR Version: 3.0 Date: 2019-03-06 Document version: 2.6 Authors: Neo-Brahmi Generation Panel [NBGP] 1. General Information/ Overview/ Abstract The purpose of this document is to give an overview of the proposed Kannada LGR in the XML format and the rationale behind the design decisions taken. It includes a discussion of relevant features of the script, the communities or languages using it, the process and methodology used and information on the contributors. The formal specification of the LGR can be found in the accompanying XML document: proposal-kannada-lgr-06mar19-en.xml Labels for testing can be found in the accompanying text document: kannada-test-labels-06mar19-en.txt 2. Script for which the LGR is Proposed ISO 15924 Code: Knda ISO 15924 N°: 345 ISO 15924 English Name: Kannada Latin transliteration of the native script name: Native name of the script: ಕನ#ಡ Maximal Starting Repertoire (MSR) version: MSR-4 Some languages using the script and their ISO 639-3 codes: Kannada (kan), Tulu (tcy), Beary, Konkani (kok), Havyaka, Kodava (kfa) 1 Proposal for a Kannada Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR) 3. Background on Script and Principal Languages Using It 3.1 Kannada language Kannada is one of the scheduled languages of India. It is spoken predominantly by the people of Karnataka State of India. It is one of the major languages among the Dravidian languages. Kannada is also spoken by significant linguistic minorities in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Kerala, Goa and abroad. -

From Conversion to Subversion a Selection.Pdf

2014 FROM CONVERSION TO SUBVERSION: 250 years of the printed book in India 2014 From Conversion to Subversion: 250 years of the printed book in India. A catalogue by Graham Shaw and John Randall ©Graham Shaw and John Randall Produced and published in 2014 by John Randall (Books of Asia) G26, Atlas Business Park, Rye, East Sussex TN31 7TE, UK. Email: [email protected] All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior permission in writing of the publisher and copyright holder. Designed by [email protected], Devon Printed and bound by Healeys Print Group, Suffolk FROM CONVERSION TO SUBVERSION: 250 years of the printed book in India his catalogue features 125 works spanning While printing in southern India in the 18th the history of print in India and exemplify- century was almost exclusively Christian and Ting the vast range of published material produced evangelical, the first book to be printed in over 250 years. northern India was Halhed’s A Grammar of the The western technology of printing with Bengal Language (3), a product of the East India movable metal types was introduced into India Company’s Press at Hooghly in 1778. Thus by the Portuguese as early as 1556 and used inter- began a fertile period for publishing, fostered mittently until the late 17th century. The initial by Governor-General Warren Hastings and led output was meagre, the subject matter over- by Sir William Jones and his generation of great whelmingly religious, and distribution confined orientalists, who produced a number of superb to Portuguese enclaves. -

Toward a Definitive Grammar of Bengali - a Practical Study and Critique of Research on Selected Grammatical Structures

TOWARD A DEFINITIVE GRAMMAR OF BENGALI - A PRACTICAL STUDY AND CRITIQUE OF RESEARCH ON SELECTED GRAMMATICAL STRUCTURES HANNE-RUTH THOMPSON Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD SOUTH ASIA DEPARTMENT SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES LONDON O c t o b e r ZOO Laf ProQuest Number: 10672939 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672939 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT This thesis is a contribution to a deeper understanding of selected Bengali grammatical structures as far as their syntactic and semantic properties are concerned. It questions traditional interpretations and takes a practical approach in the detailed investigation of actual language use. My methodology is based on the belief that clarity and inquisitiveness should take precedence over alliance to particular grammar theories and that there is still much to discover about the way the Bengali language works. Chapter 1 This chapter on non-finite verb forms discusses the occurrences and functions of Bengali non-finite verb forms and concentrates particularly on the overlap of infinitives and verbal nouns, the distinguishing features between infinitives and present participles, the semantic properties of verbal adjectives and the syntactic restrictions of perfective participles. -

Bangladesh: Urdu-Speaking “Biharis” Seek Recognition, Respect and Rights Bangladesh: Urdu-Speaking “Biharis” Seek Recognition, Respect and Rights

BANGLADESH: URDU-SPEAKING “BIHARIS” SEEK RECOGNITION, RESPECT AND RIGHTS BANGLADESH: URDU-SPEAKING “BIHARIS” SEEK RECOGNITION, RESPECT AND RIGHTS International Republican Institute IRI.org @IRIglobal © 2020 All Rights Reserved Bangladesh: Urdu-Speaking “Biharis” Seek Recognition, Respect and Rights Copyright © 2020 International Republican Institute. All rights reserved. Permission Statement: No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without the written permission of the International Republican Institute. Requests for permission should include the following information: • The title of the document for which permission to copy material is desired. • A description of the material for which permission to copy is desired. • The purpose for which the copied material will be used and the manner in which it will be used. • Your name, title, company or organization name, telephone number, fax number, e-mail address and mailing address. Please send all requests for permission to: Attn: Department of External Affairs International Republican Institute 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20005 [email protected] Cover Image Description: Aerial view of the Biharis Relief Camp, known as the “Geneva Camp.” IRI | BANGLADESH • Urdu-Speaking “Biharis” 3 OVERVIEW In early 2020, the International Republican Institute (IRI) conducted a qualitative research study of the Bihari community in Bangladesh — an Urdu-speaking linguistic minority group in the South Asian nation. The study examined the challenges and needs of Biharis in different locations around Bangladesh. The term “Bihari” refers to approximately 300,000 non-Bengali, Urdu-speaking citizens of Bangladesh who came to what was then East Pakistan mostly from the Indian states of Bihar and West Bengal after the Partition of India in 1947.